presuppositional apologetics

Really Recommended Posts 4/8/16- Lewis, Van Til, headship, and more!

Just got back from vacation in Washington state. Wow, it is beautiful there! Anyway, I have another round of links for you, dear readers. We have free writings from Cornelius Van Til, a problem for post-Flood models of diversification, C.S. Lewis, and discussion of “male headship.” Check them out and let me know what you think!

Just got back from vacation in Washington state. Wow, it is beautiful there! Anyway, I have another round of links for you, dear readers. We have free writings from Cornelius Van Til, a problem for post-Flood models of diversification, C.S. Lewis, and discussion of “male headship.” Check them out and let me know what you think!

Cornelius Van Til free downloads– Cornelius Van Til was an advocate of presuppositional apologetics. I have written extensively on presuppositionalism myself. Van Til is probably the best-known advocate of the method. Here are free readings from him.

The Great Genetic Bottleneck that Contradicts Ken Ham’s Radical Accelerated Diversification– Ken Ham advocates a kind of hyper-diversification after the Flood which allows for the number of species we see today. What

Christian Thinkers 101: A Crash Course on C.S. Lewis– C.S. Lewis is one of the greatest Christian thinkers of the 20th century. Here’s a great post (with infographic!) that gives tons of information on his life and thought.

5 Myths of Male Headship– The concept of “headship” is often a product more of our own assumptions than of the biblical text. Here is a post that shows 5 myths about male headship that are often assumed.

Book Review: “Expository Apologetics” by Voddie Baucham, Jr.

Expository Apologetics by Voddie Baucham, Jr. puts forward an apologetics methodology that is largely presuppositional in its approach. The core of Baucham’s approach is the use of biblical texts in engaging with those who do not believe.

Expository Apologetics by Voddie Baucham, Jr. puts forward an apologetics methodology that is largely presuppositional in its approach. The core of Baucham’s approach is the use of biblical texts in engaging with those who do not believe.

A central aspect of Baucham’s methodology is the notion that the problem of unbelieve is not a lack of information but rather sin. He bases this claim on an interpretation of Romans 1 that is very much in line with that of other presuppositional apologists (see my post on the topic here). Because of this, Baucham alleges, apologetic approaches which approach others with information (such as an argument for the existence of God) rather than the Gospel (i.e. direct exposition of the Bible) fail.

Baucham also appeals to Scripture throughout the book, noting that the use of God’s word ought to be central to our lives as Christians and therefore central to our witness. He argues rightly that every single Christian ought to be engaged in apologetics; it is not something merely for experts.

Chapter 5, which emphasized learning apologetics through the use of historical creeds, confessions, and catechisms, was an excellent piece of advice for apologists. This was a breath of fresh air as too often Christians ignore the historical definitions of faith which are full of the richness of Christian thinkers throughout time. Baucham notes that anyone who attempts to dismiss a creedal tradition by saying “No creed but the Bible” has already made their own creed to which they adhere.

The book has many applicable insights into doing apologetics. This is worth taking note of, because often introductory apologetics books claim to present a method, but then never show that method in action. This makes it difficult to actually understand how to do apologetics or what is even meant by all the discussion about method. Baucham, however, continually uses examples that have direct practical application. Chapter 9 “Preaching and Teaching Like an Expository Apologist” is full of practical insights for apologists trained and untrained. Chapter 8 applied various ways to answer objections to a number of different situations. I appreciated how much practical advice is found throughout the book. It should be noted that a primary target for these practical engagements is same-sex marriage. It would have been nice to have the focus be on atheism rather than on specific moral issues, but the practical advice given can be applied to other situations as well.

A serious question might be raised about the audience of the book. Baucham claims that it is for “everyone” but then goes on to outline the audiences he intends. “The first audience is the heathen” (Kindle location 293). Surely, the use of this term will prejudice those who do not believe towards the book immediately. Heathen has come to be understood as very pejorative, and it is difficult to see why it was chosen. Moreover, he adopts the biblical use of the term “fool” not just in its technical sense, but also throughout the book to refer to those who do not believe. One wonders whetherthose who are described as heathen fools would be willing to read the book.

Another difficulty with the book is Baucham’s suggestion that children are basically little unbelievers. This stands in contrast to the notion of having faith like a child (which suggests that children have faith). Elsewhere, Baucham discusses the question one of his children asked him and how it demonstrated this child had not come to faith in Christ yet. But of course children ask questions about all kinds of things, and this does not entail they don’t believe in them. Indeed, Baucham’s continual assertion that unbelief is a problem of sin rather than information suggests that he is going against his own advice here. He treats his own children’s information problem as though this proves they are atheistic. This kind of theology is deeply troubling, and it cuts against the grain of Jesus’ own words about little children coming to him and having faith such as those little children.

The critique of other apologetic methods is also off base. For example, Baucham is highly critical of any method which does not use Scripture throughout the whole process. He cites a number of verses that speak of the power of God’s word, as well as other presuppositional thinkers like Sye Ten Bruggencate to forcefully admonish those apologists who use other forms of apologetics. However, such a critique is fundamentally flawed, for despite presuppositionalists’ commitment to realizing the epistemic effects of sin, they maintain this critique despite the fact that atheists often immediately shut down conversation–whether by refusing to continue, mocking, or the like–when the Christian cites Scripture. Baucham allows for this in some fashion by coming sidelong with Scriptural principles rather than direct citations, but if that is his position, then his whole critique is misguided to begin with! After all, a Scriptural principle is surely that God exists. Ergo, an apologist seeking to prove that God exists without explicitly citing Scripture is permitted to do so on Baucham’s own view, despite his critique of that very same apologist.

For some reason, Baucham also clings to using male pronouns for everything throughout the book, referring to humanity as “man,” and talking about all believers as “men.” Interestingly, the only female pronoun I noticed being used generically in the whole book was for an atheist “interlocutor.” When portions of the book refer to not needing to be seen as wise by “men” and or needing to be thought of well by “men,” one wonders whether Baucham simply dismisses women’s opinions entirely.

Expository Apologetics is an ultimately uneven ride introducing presuppositional apologetics to a broad audience. There is much applicable knowledge here, to be sure. However, it is alongside some poor arguments against other apologetic methods, questionable use of terminology, and some disturbing theological conclusions. It’s worth the read for the applicable knowledge, but there are many pitfalls to be found.

The Good

+Emphasizes the notion that every Christian should be an apologist

+Creeds seen as major point to drive apologetics

+Good amount of practical application to apologetics

The Bad

-Poor use of terminology

-Suggests children are to be treated as unbelievers

-Consistently uses male pronouns and “man” instead of gender inclusive language

-Dismisses other forms of apologetics

Disclaimer: I was provided with a copy of this book for review by the publisher. I was not required to write any specific kind of feedback whatsoever.

Source

Voddie Baucham, Jr. Expository Apologetics (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2015).

Links

The Unbeliever Knows God: Presuppositional Apologetics and Atheism– I write about the notion that all people have knowledge of God whether that is acknowledged or not. This has great implications for apologetics of all methods.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

Eclectic Theist– My other interests site is full of science fiction, fantasy, food, sports, and more random thoughts. Come on by and check it out!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Really Recommended Posts 4/3/15- Golden Son, Tyndale, Judaism, and more!

Today is Good Friday. Let us reflect upon the greatness of God and the power of the Son for our salvation. Amen!

Now, be sure you also dive into this reading material as I have collected it from all corners of the internet for you, dear readers. A broad array of topics is here for your reading pleasure.

Golden Son (Red Rising)– Golden Son is book two of a trilogy by Pierce Brown which is quite interesting. I reviewed the first book myself here. Anthony Weber’s look at the second book provides some solid insights into this YA novel and human nature.

Reject Jesus for Judaism?– A great question and answer about whether it is more reasonable to reject Jesus and embrace Judaism.

“Feminist” is not a Dirty Word– Too often, we see the word “feminist” and react against it with a whole slew of beliefs about what the word must mean before we ask the person who self-identifies as such what it does mean. Here’s a good read to get some insight into the matter.

Tyndale (Comic)- Who was Tyndale and why does he matter? Here’s a neat little comic that answers these and other questions.

Evaluating RC Sproul’s Objection to Presuppositional Apologetics at the Inerrancy Summit– Apologetic method is a debate I try to avoid generally because I think that we need to realize that different approaches will work better for different people and situations. I favor an integrated approach with different methods meshed together. Here’s a look at one objection to the presuppositional method and a response from a presuppositional apologist. What are your thoughts on the matter?

Question of the Week: Which apologetic method do you prefer?

Each Week on Saturday, I’ll be asking a “Question of the Week.” I’d love your input and discussion! Ask a good question in the comments and it may show up as the next week’s question! I may answer the questions in the comments myself.

Each Week on Saturday, I’ll be asking a “Question of the Week.” I’d love your input and discussion! Ask a good question in the comments and it may show up as the next week’s question! I may answer the questions in the comments myself.

Apologetic Method

There are a number of different apologetic methods, such as evidentialism, presuppositionalism, classical apologetics, cumulative-case apologetics, Reformed Epistemology, and some even consider forms of fideism to be a type of apologetics.

I’m curious as to what your preferred apologetic method is:

Which apologetics method do you prefer? Do you consider it to be the only method which is viable?

There are some who argue that, for example, presuppositionalism is the only biblical apologetic method. Others (like myself) prefer an integrative approach which uses aspects of as many different approaches as possible. What are your thoughts? How have you used your apologetic approach most effectively? Let me know in the comments!

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more.

Question of the Week– Check out other questions and give me some answers!

SDG.

Book Review: “Faith Founded on Fact” by John Warwick Montgomery

John Warwick Montgomery (hereafter JWM) is about as evidentialist as they come, and Faith Founded on Fact: Essays in Evidential Apologetics

John Warwick Montgomery (hereafter JWM) is about as evidentialist as they come, and Faith Founded on Fact: Essays in Evidential Apologetics is a collection of his essays which shows, through application, his apologetic method from a number of contexts. Here, I will go through the book to highlight main points of the individual essays and the book as a whole. Then, we’ll discuss some of the main theses in the text. Be sure to leave a comment to let me know what you think of JWM’s theses.

Central to JWM’s apologetic methodology is the notion that one need not presuppose the truth of the Bible in order to defend it. For him, one may make the appeal to the skeptic by going to the skeptic and battling their reasoning on their own grounds. He states his thesis succinctly:

Few non-Christians will be impressed by arguments… in which the Christian stacks the deck by first defining ‘rationality’ and ‘internal consistency’ in terms of the content of his own revelational position and then judges all other positions by that self-serving criterion. (xix, cited below)

JWM surveys various attacks on the practice of evidential apologetics and argues that they fail (28ff). Although he deals with various liberal objections to apologetics, the core of his concern is for the objections raised by those who feel as though the evidentialist approach does injustice to faith. In response, he notes that any approach which removes Jesus from historical investigation–from hard evidence capable of being explored by all–reduces Him to a “historical phantasm” and does injustice to the reality of the incarnation (34-35).

The possibility of miracles and the argument of Hume engages in “circular reasoning” for Hume’s argument relies upon “unalterable experience” which is, of course his own experience and that of those who agree with him. Moreover, the definition of miracle has been slanted in such a way as to make it either irrelevant or beyond the realm of evidence by various parties (46ff). A case study of the miracle of the resurrection provides proof that miracles may be examined with an evidentialist mentality, for any who wish to deny the notion must relegate history to a place which may never be accessed through evidence (56ff).

JWM analyzes Muslim apologetics and concludes that it provides a number of lessons for Christian apologetists. Among these is the notion that merely showing the falsity of other religions is not enough for an evidential defense (93-94), the notion that “no religion is deducible from self-evident a prioris…” (97), and mere appeal to “try out” a religion is not enough to establish its credibility (98).

One of JWM’s most famous (or infamous, depending upon your view) essays is “Once Upon an A Priori,” in which he launched a broad-spectrum attack on presuppositional apologetics as a methodology. In this essay, JWM argues that when one suggests there is no neutral epistemic ground between two positions whatsoever–as presuppositional apologists do–“Neither viewpoint can prevail, since by definition all appeal to neutral evidencve is eliminated” (115). Because there are no neutral facts, there can be no appeal to facts to make one’s case; instead, all one is able to do is argue in circles against each other… “appeal to common facts is the only preservative against philosophical solipsism and religious anarchy…” (119). Instead, Christians must, like Paul, “become all things to all” people (122) in order to make the case for Christianity.

The practice of apologetics, for JWM, is intended to break down the barriers to belief. But the evidences are so strong that they obligate belief in Christian theism. However, the work of the Spirit is the work of conversion. The “evidential facts are God’s work, and the sinner’s personal acceptance of them… is entirely the product of the Holy Spirit” (150).

After an essay appealing to Christians to continue to use mass communication to spread the Word, JWM turns to “The Fuzzification of Biblical Inerrancy.” By “fuzzification,” he means (following James Boren), “the presentation of a matter in terms that permit adjustive interpretation” (217). In its application to inerrancy, it means the constant adjustment of inerrancy to make it invulnerable to attack in often ad hoc ways. What one is left with is “inerrancy devoid of meaningful content…” (223). In order to combat this, JWM suggests explicit definitions of terms such that one has a firm grasp upon what is meant by inerrancy, rather than a constant modification of the term and meaning.

There are a few areas of disagreement I would express with JWM’s theses. First, his apparent dismissal of the practice of taking the “falsity of one religion” as proof of another (93-94). He is correct in that the falsity of any given religion does not entail the truth of any other one. However, it seems to be the case that the falsity of any one religion does entail that any which have not been proven false are inherently more probable. Second, I think his reaction against presuppositionalism has led him to reject all of its tenets a bit too vehemently. For example, it seems to me that in his rejection of the notion there can be “no neutral ground” he also seems to jettison the notion that facts are interpreted no matter what the facts are. However, at times it is difficult to distinguish whether he is making a statement in a vaccuum or against a context. In relation to “facts,” he clearly holds the facts are determinative enough to demonstrate Christianity; but he also holds that people will not accept said facts other than through God’s action. Thus, perhaps the gulf between his position and that which he rejects is not so wide.

These disagreements aside, I also have enormous respect for and agreement with much of the content of Faith Founded on Fact. JWM effectively disposed of any apologetic method which inherently ignores the value of evidentialist reasoning, and he did so through not only apologetic but also theological reasons (i.e. it turns Christ into an “historical phantasm”). Moreover, his critique of presuppositional methodology–though at times off base (as noted above), does not entirely miss the mark. In particular, his critique that presuppositionalism voids any kind of objective method for determining facts is troubling for those who have presuppositional tendencies (readers should note that I myself think presuppositionalism has some merit–see my posts on the topic).

Faith Founded on Fact, put simply, is fantastic. In this review, I have only surveyed a small number of the areas I found to be of note throughout the work. JWM is witty and clever as usual, but he also raises an enormous number of points to reflect upon whether one agrees with his views or not. He offers a number of ways to approach apologetics from an evidentialist perspective, while also offering some devastating critiques of those who would allege that evidentialism fails. The book is a must read for anyone interested in apologetics.

Links

“How Much Evidence to Justify Religious Conversion?” – John Warwick Montgomery on Conversion– I summarize and analyze an incredible lecture given by John Warwick Montgomery which I had the pleasure of attending at 2012’s Evangelical Theological Society Conference. JWM argues for an evidential view of religious conversion.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Source

John Warwick Montgomery, Faith Founded on Fact: Essays in Evidential Apologetics (Edmonton, AB, Canada: Canadian Institute for Law, Theology, and Public Policy Inc., 2001).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Ken Ham vs. Bill Nye- An analysis of a lose-lose debate

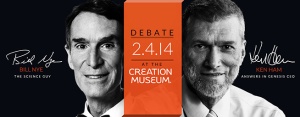

Today, Ken Ham, a young earth creationist, debated against Bill Nye an agnostic famous for “The Science Guy” program, on the topic: “Is creation a viable model of origins in today’s scientific era?” The debate was watched by over 500,000 people and generated a huge amount of interest. Here, I’ll review the debate section by section. Then, I’ll offer some thoughts on the content as well as a concluding summary. If you watched the debate, you may want to just skip down to the Analysis section. The debate may be watched here for a limited time (skip to 13 minutes in to start debate).

Today, Ken Ham, a young earth creationist, debated against Bill Nye an agnostic famous for “The Science Guy” program, on the topic: “Is creation a viable model of origins in today’s scientific era?” The debate was watched by over 500,000 people and generated a huge amount of interest. Here, I’ll review the debate section by section. Then, I’ll offer some thoughts on the content as well as a concluding summary. If you watched the debate, you may want to just skip down to the Analysis section. The debate may be watched here for a limited time (skip to 13 minutes in to start debate).

Ken Ham Opening

Ham began by noting that many prominent scientists argue that scientists should not debate creationists. He wondered aloud whether that might be because creationism is indeed a viable model and some don’t want that to be shown. He then showed a video of a creationist who was a specialist in science and an inventor, noting that creationism is not mutually exclusive from science.

The three primary points Ham focused on were 1) the definitions of terms; 2) interpretation of the evidence; and 3) the age of the universe is not observational science. Regarding the first, Ham noted that science means knowledge and so evolutionists cannot claim to be doing science. Regarding the second, he argued that both creationists and evolutionists observe the same evidence; they simply interpret that evidence differently. Regarding the third, Ham observed that “We weren’t there” at the beginning of the Earth and so we can’t know through observational science what happened.

Bill Nye Opening

Nye noted that the primary contention of the topic was to see whether the creation model lined up with the evidence. Thus, we must compare Ken Ham’s creation model to the “mainstream” model of science (his word). There are, he contended, major difficulties with Ham’s model, including the fossils found in layers in the Grand Canyon. He noted that there is “not a single place” where fossils of one type cross over with fossils of a different type or era. Yet, on a creation model, one would expect vast amounts of mixing. Thus, the creation model fails to account for the observational evidence.

Nye also noted that there are “billions of people ” who are religious and do not hold to creation science.

Ham Presentation

Ham again emphasized the importance of defining terms. He then presented a few more videos of creationists who are active scientists in various fields. One, a Stuart Burgess [I think I typed that correctly] claimed that he knew many colleagues who expressed interest in creationism but were afraid for their careers.

Non-Christians, Ham alleged, are borrowing from the Christian worldview in order to do science. The reason for this is because their own worldview cannot account for the laws of logic, the uniformity of nature, or the laws of nature. He asked Nye to explain how to account for these aspects of reality without God.

The past cannot be observed directly, he said, and concluded that we can’t be certain that the present is like the past. Thus, we must only deal with the observed facts that we can see now. On this point, the disagreements are over the interpretation of the evidence. That is, there is a set of evidence that both people like Nye and Ham approach. According to Ham, it is their worldviews which color their interpretation of the evidence such that they use the same evidence and get entirely contradictory conclusions.

The diversity of species which is observed is only, Ham argued, difference in “kind.” Thus, it cannot be used as evidence for evolution. The word “evolution” has been “hijacked” and used as evidence for unobservable phenomena extrapolated from that which is observed. The various species demonstrate a “creation orchard” as opposed to an “evolutionary tree.” One may observe different creatures, like dogs, each stemming from an a common origin, but none of these are traceable back to common descent, rather they exhibit discontinuity in the fossil record.

There is a major difference, Ham alleged, between “observational sciences” which looks at the things we can see in repeatable events now and “historical sciences” which extrapolates from the evidence gathered what happened in the past. We can never truly have “knowledge” regarding the historical sciences.

Nye Presentation

Nye began his presentation by noting that the debate took place in Kentucky and “here… we’re standing on layer upon layer upon layer of limestone.” The limestone is made of fossils of creatures which lived entire lives (twenty or more years in many cases) and then died, piled up on top of each other, and formed the limestone underneath much of the state. The amount of time needed for this is much longer than just a few thousand years.

Nye also turned to evidence from ice cores, which would require 170 winter/summer cycles per year for at least a thousand years to generate the current amount of ice built up. In California, there are trees which are extremely ancient, and some trees are even older, possibly as old as 9000 or more years old. Apart from the difficulty of the age of these trees, one must also wonder how they survived a catastrophic flood.

When looking at a place like the Grand Canyon, one never finds lower layer animals mixed with higher level animals. One should expect to find these given a flood. Nye challenged Ham to present just one evidence of the mixing of fossils of different eras together; he said it would be a major blow to the majority sciences.

If the flood explains animal life and its survival, one should observe the migration of animals across the earth in the fossil record; thus a Kangaroo should be found not just in Australia but along the way from wherever the Ark rested. However, these finds are not observed. Finally, the Big Bang has multiple lines of evidence which confirm it as the origin of the universe.

Ham Rebuttal

Ham argued that we can’t observe the age of the Earth. No science can measure it through observational evidence; rather it falls under historical sciences. One should add the genealogies in the Genesis account in order to find the age of the Earth. Whenever a scientist talks about the past, “we’ve got a problem” because they are not speaking from observation: they were not there.

Various radiometric dating methods turn up radically divergent ages for artifacts from the same time period and layer of rocks. The only infallible interpreter of the evidence is God, who provided a record in the Bible.

Nye Rebuttal

Rocks are able to slide in such a way as to interpose different dated objects next to each other.

Nye noted that Ham kept saying we “can’t observe the past,” but that is exactly what is done in astronomy: no observation of stars is not observing the past. Indeed, it takes a certain amount of time for the light to get to Earth from these various stars. The notion that lions and the like ate vegetables is, he argued, preposterous. Perhaps, he asserted, the difficulty is with Ham’s interpretation of the biblical text.

Nye then compared the transmission of the text of the Bible to the telephone game.

Ham Counter-Rebuttal

Ham again pressed that natural laws only work within a biblical worldview. There only needed to be about 1000 kinds represented aboard the ark in order to represent all the current species. Bears have sharp teeth yet eat vegetables.

Nye Counter-Rebuttal

Nye asserted that Ham’s view fails to address fundamental questions like the layers of ice. The notion that there were even fewer “kinds” (about 1000) means that the problem for Ham is even greater: the species would have had to evolve at extremely rapid rates, sometimes even several species a day, in order to account for all the differences of species today.

Q+A

I’ll not cover every single question, instead, I wanted to make note of two major things that came up in the Q+A session.

First, Nye’s answer to any question which challenged him on things like where the matter for the Big Bang came from was to assert that it’s a great mystery and we should find out one day. Second, Ham’s response to any question which (even hypothetically) asked him to consider the possibility that he would be wrong was to assert that such a situation was impossible. In other words, he presupposed he was correct and held to the impossibility that he could be wrong.

Analysis

Ken Ham

Ken Ham’s position was based upon his presuppositional apologetic. He continued to press that it is one’s worldview which colors the interpretation of evidence. The facts, he argued, remained the same for either side. It was what they brought to the facts that led to the radically different interpretations.

There is something to be said for this; it is surely true that we do have assumptions we bring to the table when interpreting the evidence. However, apart from the problem that Ham’s presuppositional approach with creationism is unjustified, Ham failed to deal with facts which really do shoot major holes in his theory. For example, it simply is true that, as Nye noted, when we observe the stars or distant galaxies, we are observing the past. Ham was just wrong on this regard. Moreover, other observational evidence (though not directly showing the past) does demonstrate that the Earth cannot be so young as Ham supposes. Furthermore, his hard and fast distinction between historical sciences and observational sciences is more of a rhetorical device than anything.

Ham’s position, I would argue, fails to account for the evidence which Nye raised (along with a number of other difficulties). Moreover, he continued to paint a picture of the Bible which rejects any but his own interpretation. In other words, he presented a false dichotomy: either young earth creationism or compromise with naturalism. However, I did appreciate Ham’s focus on the Gospel message. It was refreshing to have him present a call to belief in Jesus Christ as Lord and savior in front of such a massive audience.

Bill Nye

Nye did an okay job of trying to show that there may be more to the debate than simply creationism-or-bust for Christianity. Indeed, he actually went so far as to say there is “no conflict” between science and faith. Instead, he argued that Ham’s position is the one which generates such a conflict. His rebuttals provided some major reasons to think that Ham’s creationism could not account for the evidence. In particular, the difficulties presented by the proliferation of species after the flood and the fossil record were solid evidences.

However, Nye’s presentations had a couple difficulties. First, he failed to account for polystrate fossils: the very thing he challenged Ham to present. There really are such things as fossils which are found out of sequence (thanks to ElijiahT and SkepticismFirst on Twitter for this). That’s not to say they prove young earth creationism. Far from it. So Nye seems to have been mistaken on this point. Second, he presented the Big Bang theory as though Fred Hoyle somehow came up with the hypothesis, yet Hoyle is well known for denying the Big Bang. Third, the notion that the interpretation, translation, and transmission of the Bible through time is anything like the telephone game is a tiresome and simply mistaken metaphor.

Both

Both men were extremely respectful and I appreciated their candor. Each had several good points; each had some major flaws in their positions. The dialogue as a whole was interesting and helpful.

Conclusion

Readers by now should realize that I have to confess my title is a bit misleading. I was impressed by the tone of both speakers, though I thought they each made major gaffes alongside some decent points. The bottom line is that I find it unfortunate that we were exposed to a false dichotomy: either creationism or naturalism. There is more to the story. As far as “who won” the debate, I would argue that because of this false dichotomy, neither truly won. However, it seemed to me Ham had a more cohesive 30 presentation. That is, his presentation stayed more focused. Nye’s presentation jumped around quite a bit and had less directness to it. So far as “debate tactics” are concerned, one might chalk that up to a win for Ham. However, Nye successfully dismantled Ham’s presentation in the rebuttal periods. Thus, one was left with the impression that Ham’s view was indeed based upon his presupposition of its truth, while Nye was more open to the evidence. Again, I think both are wrong in many areas, but I hope that Nye’s tearing down of Ham’s position will not demonstrate to some that Christianity is false. As Nye noted, it may instead be Ham’s interpretation which is wrong.

There was much more to cover here than I could get to, so please do leave a comment to continue the discussion.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Naturalis Historia– This site is maintained by a biologist who presents a number of serious difficulties for young earth creationism.

Gregg Davidson vs. Andrew Snelling on the Age of the Earth– I attended a debate between an old earth and young earth creationist (the latter from Answers in Genesis like Ken Ham). Check out my overview of the debate as well as my analysis.

Debate Review: Fazale Rana vs. Michael Ruse on “The Origin of Life: Evolution vs. Design”– Theist Fazale Rana debated atheist Michael Ruse on the origin of life. I found this a highly informative and respectful debate.

Reasons to Believe– a science-faith think tank from an old-earth perspective.

Other Reviews of the Debate

Ken Ham vs. Bill Nye post-debate analysis– The GeoChristian has a brief overview of the debate with a focus on what each got right or wrong.

Ken Ham vs. Bill Nye: The Aftermath– Luke Nix over at Faithful Thinkers has another thoughtful review. His post focuses much more on the topic of the debate as opposed to a broad overview. Highly recommended.

Ken Ham vs. Bill Nye: The Debate of the Decade?- Interested in what led up to this debate? Check out my previous post on the topic in which I urged Christians to write on this debate and also traced, briefly, the controversy leading up to this debate.

The image used in this post is was retrieved at Christianity Today and I believe it’s origin is with Answers in Genesis. I use it under fair use to critique the views. I make no claims to owning the rights to the image, and I believe the image, as well as “The Creation Museum” are copyright of Answers in Genesis.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Hardwired: Finding the God You Already Know” by James Miller

Irreverent. That’s how I would describe Hardwired

Irreverent. That’s how I would describe Hardwired by James Miller in one word. Miller appeared unimpressed by Natural Theology, and perhaps even less impressed by current scholarly apologetics. Yet this is, unabashedly, an apologetics work. It’s just not the type that many readers would expect going in. Miller’s approach is presuppositional: that is, he sought to discuss the questions about faith by analyzing those things that people already assume or know.

Illustrative was his comment early on in the work. Miller was approached by a mother who was heartbroken over her son leaving the faith. She asked him, “‘How do I convince him there is a God?'” Miller’s answer is indicative of his apologetic method: “He already believes in God.” This startling statement forms the basis for the rest of the book. Miller’s approach revolved around showing people the God they “already know.”

How might one justify this outlandish claim? First, Miller argued that human beings are not “blank slates”–that is, the human mind is in fact shaping that which it observes even as it observes it: “You and I, witnessing events through the same pair of glasses, would not know the same thing, because your brain and my brain do different things with the knowledge” (42). All knowledge is filtered through the preconceptions one has that sorts it into different levels of experience. Miller provided several reasons for thinking that the notion of our minds as blank slates is wrong (42-44; see also 58-61).

The notion that we are not “blank slates” also means that we filter ideas through a number of pre-existing categories. It also means that a wholly objective approach to discovering truth is impossible; we simply cannot step entirely outside of our presuppositions about reality. Moreover, human beings seem to have a shared experience of certain affirmations, even though some may attempt to deny them. For example, “we assume that our perceptions of the world… are accurate… We assume that there are real moral rights and wrongs… We assume that life has a purpose… We assume that there can be meaningful communication in which two people accurately share what they are thinking” (26). These assumptions are not uncontroversial; indeed, many have sought to deny any or all of them. Hardwired featured concise arguments for the fact of each of these notions.

Apart from these seemingly universal human experiences, Miller also argued that the very position of agnosticism is one which does not cohere with reality. Agnosticism is fundamentally a witholding of belief, but that is itself based upon a supposed ignorance of all the available data. He compared it to a court case regarding evidence: “People are only off the hook when they can show both that they didn’t know and that there was no way they could have known.” It is not enough to plead ignorance: “they are still guilty if they didn’t know because they avoided finding out” (55). The Bible clearly states that all people are capable of knowing God, and stand without excuse (Romans 1). “The onus is on honest agnostics to produce a pretty substantial bibliography of failed research” (56).

The fact of God’s existence may be found throughout reality, argued Miller. First, there is the reality of religious experience, but Miller prefers to view these as “epiphanies” which are “a sudden piercing discovery…” which may “draw our attention to things we’ve previously taken for granted or ignored” (69). Second, the existence of moral absolutes is a universal experience. However, this is not to be taken as a proof for God; rather Miller suggested that it means we have “inclinations that cannot be filled by anything but the exisence of God” (91). Even the atheistic moral objection to the God of the Bible assumes objective morality, because it assumes that they are capable of discerning real right and wrong (91-92). The very fact of valuation hints at the Creator (108-111).

The Christian faith gives compelling reasons to believe because its story matches and exceeds the criterion of embarrassment: its “hero,” Jesus, is scorned and shamed, not glorified and given rule over all nations (121ff).

The existence of God, Miller argued, is not tied to arguments or debates, rather, “What convicts us of the existence of God [are]… the soft, subjective facts of an experience that resonates with human longing and confirms are deep suspicions” (156). Hardwired is Miller’s attempt to point to those experiential factors.

By way of analysis, I first note that I think Miller has done an excellent job summarizing a number of extremely complex and difficult issues in ways that the “person on the street” could pick up the book and understand. He is concise and clear. Moreover, I sympathize in many ways with his approach. It seems to me to be true that humans cannot approach a topic as though we are “blank slates” ready to take whatever input we are given without layers of interpretation. That, I think, is the greatest strength of Miller’s approach. He pointed out the deeply seeded assumptions we hold which influence the way we view reality and showed how these lead to God.

However, I wonder about the coherence to Miller’s approach. His critique of natural theology does not sit well with his appeal to some of the very types of arguments that natural theologians use. For example, his appeal to objective morality is essentially no different from the defense provided for the “moral argument” by natural theologians like William Lane Craig, whose approach Miller criticizes. His presuppositional argument itself depends upon some forms of evidentialism (and here I am intentionally wording this to avoid being accused of being unaware of the fact that presuppositional apologists do use evidence–it is manifestly true that even the staunchest presuppositional apologist uses evidence… my point is that the method Miller uses is often evidentialist in its approach). Ultimately, readers will be left with what essentially amounts to an existentialist evidentialism, which seems itself to rely upon natural theology in a number of traceable ways.

Another difficulty I had with Hardwired is that it seemed Miller sometimes overstated his case. Perhaps the most obvious example of this, in my opinion, is his discussion of evolution. He discussed natural selection and sought to evaluate it by looking at humans: “[I]f natural selection actually works, a few million years should make for some pretty shiny, strong, effective gladiators who have good teeth and rarely catch cold… Specifically, there are some traits of humanity that should by all means have been weeded out by now: sleep (which makes people vulnerable to predators for a third of their lives)… endoskeletons, appendices, wisdom teeth, birth defects, stupidity, and obesity” (94).

I’m not about to dive into biology, which is by no means an area of my expertise, but it seems to me that none of these are required expectations given Neo-Darwinism. Miller’s critique does not take into account the fact that humans have worked using their intelligence to circumvent many of these difficulties (i.e. we live in shelters which keep us safe while sleeping; appendices still have function; etc, etc.). The critique offered here also seems shamelessly teleological, which is the very thing Neo-Darwinists would deny within their system.

Hardwired is a brief missive which applies presuppositional apologetics in a straightforward, easy-to-understand fashion. Miller doesn’t fall into using terminology that will be difficult for the uninitiated to understand. Instead, he provides a coherent beginning-to-end approach in how to argue for faith from his presuppositional approach. It is a commendable work for its simplicity, and despite the areas of disagreement I noted above, I certainly think it is worth a read. Miller has a way of answering the difficulties that people raise against Christianity in concise but convincing fashion. It’s a mixed bag, but one well worth the time spent.

Source

James W. Miller, Hardwired: Finding the God you Already Know (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2013).

Disclaimer

I received a copy of Hardwired free of charge for review. I was only asked to give an honest review of the book.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Really Recommended Posts 8/2/13

After a brief hiatus, “Really Recommended Posts” are back. This go-round I have found for your reading/viewing pleasure a debate on sola scriptura, Buddhism, fear, the Shroud of Turin, and presuppositional apologetics. As always, let me know what you liked/didn’t like! Send me your own recommendations!

After a brief hiatus, “Really Recommended Posts” are back. This go-round I have found for your reading/viewing pleasure a debate on sola scriptura, Buddhism, fear, the Shroud of Turin, and presuppositional apologetics. As always, let me know what you liked/didn’t like! Send me your own recommendations!

Is the Bible the only infallible rule of faith? Tim Staples vs. James White (Video)- A (lengthy) debate between a Roman Catholic and a Calvinist regarding the rule of faith. Should we hold to sola scriptura, or do we need the Magisterium in order to preserve teaching? The debate is really worth listening to.

A Comparison of the Ethical teachings and Impact of Jesus and Buddha– A brief insight into comparative religions between Buddhism and Christianity. What of truth in other religions? I found this a very interesting post.

Fiction and Fear– A really excellent post over at Hieropraxis which notes the importance of an element of fear in fiction. The post ties this back to the relevance of the Christian teaching of Christ’s redeeming work.

Shroud of Turin Blog– I am not convinced that the Shroud of Turin is authentic. However, I do find some of the work being done regarding its authenticity is very interesting. This blog has a constant string of posts related to various evidences in favor of the Shroud’s authenticity. I recommend it for those interested in reading on the topic, with the caveat of my own (hopeful) skepticism.

What is pre-suppositionalism? What is presuppositional apologetics?– Over at Wintery Knight, this interesting post turned up with a critique of presuppositionalism as an epistemology (largely based on this post at The Messianic Drew). I found it interesting, though I do not fully agree with all the critiques leveled therein. For balance, I would also direct readers to Janitorial Musings for a counter-argument to the first major contention against presuppositionalism- Presuppositionalism and Circularity. I think readers should read all the posts involved for a more complete picture. Judge for yourselves what to think of the presuppositional “worldview” (to use Drew’s term–I would lean towards saying “epistemology” instead).

Inerrancy and Presuppositional Apologetics: A different approach to defending the Bible

Scripture is inerrant because the personal word of God cannot be anything other than true. -John Frame (The Doctrine of the Word of God

, 176 cited below)

One of the most difficult issues facing evangelical Christian apologists is the doctrine of inerrancy. I’m not trying to suggest the doctrine is itself problematic. Indeed, I have defended the doctrine in writing on more than one occasion. Instead, I am saying that defending this doctrine in an apologetics-related discussion is difficult. Here, I will explore one way that I think should be used more frequently when discussing the doctrine.

What is the problem?

There are any number of attacks on inerrancy and Biblical authority, generally speaking. Very often, when I discuss the Bible with others in a discussion over worldviews, I find that the challenge which is most frequently leveled against the notion of inerrancy is a series of alleged contradictions. The second most common objection is some sort of textual criticism which allegedly shows that the Bible could not be without error in its autographs. A third common argument against inerrancy is to quote specific verses and express utter incredulity at their contents.

Of course, it doesn’t help that the definition of inerrancy is often misunderstood. For simplicity’s sake, I will here operate under the definition that “The Bible, in all it teaches, is without error.” I have already written on some misconceptions about the definition of inerrancy, and readers looking for more clarification may wish to read that post.

How do we address the problem?

Most frequently, the way I have seen apologists engage with these challenges is through a series of arguments. First, they’ll argue for the general reliability of the Bible by pointing out the numerous places in which it lines up with archaeological or historical information we have. Second, they’ll argue that these historical reports given in the Bible cannot be divorced from the miraculous content contained therein. Given the accuracy with which these writers reported historical events, what basis is there to deny the miraculous events they also report?

Other apologists may establish inerrancy by rebutting arguments which are leveled against the doctrine. That is, if one puts forth an argument against inerrancy by pointing out alleged contradictions, these apologists seek to rebut those contradictions. Thus, once every single alleged error has been addressed, this approach concludes the Bible is inerrant.

Now, I’m not suggesting that either of these methods are wrong. Instead, I’m saying there is another way to approach the defense of the Bible.

A Presuppositional Defense of Inerrancy

Suppose God exists. Suppose further that this God which exists is indeed the God of classical Christian theism. Now, supposing that this is the case, what basis is there for arguing that the Bible is full of errors? For, given that the God of Christianity exists, it seems to be fairly obvious that such a God is not only capable of but would have the motivation to preserve His Word as reported in the Bible.

Or, consider the first step-by-step argument for inerrancy given in the section above, where one would present archaeological, philosophical, historical, etc. evidence point-by-point to make a case for miracles. Could it not be the case that the only reason for rejecting the miraculous reports as wholly inaccurate fictions while simultaneously acknowledging the careful historical accuracy of the authors is simply due to a worldview which cannot allow for the miraculous at the outset?

What’s the Point?

At this point one might be thinking, So what? Who cares?

Well, to answer this head on: my point is that one’s overall worldview is almost certainly going to determine how one views inerrancy. The point may seem obvious, but I think it is worth making very explicit. If we already hold to a Christian worldview broadly, then alleged contradictions in the Bible seem to be much less likely–after all, God, who cannot lie (Numbers 23:19), has given us this text as His Word. Here it is worth affirming again what John Frame said above: the Bible is inerrant because it is of God, who is true.

Thus, if one is to get just one takeaway from this entire post, my hope would be that it is this: ultimately the issue of Biblical inerrancy does not stand or fall on whether can rebut or explain individual alleged errors in the Bible–it stands or falls on one’s worldview.

One final objection may be noted: Some Christians do not believe in inerrancy, so it seems to go beyond an issue of worldview after all. Well yes, that is true. I’m not saying a defense of inerrancy is utterly reducible down to whether or not one is a Christian or not–as I said, I think evidential arguments are very powerful in their own right. I am saying that inerrancy is impossible given the prior probabilities assigned by non-Christian worldviews and altogether plausible (not certain) given Christian worldview assumptions.

A Positive Case for Inerrancy

Too often, defense of inerrancy take the via negativa–it proceeds simply by refuting objections to the doctrine. Here, my goal is to present, in brief, a positive argument for inerrancy. The argument I am proposing here looks something like this (and I admit readily that I have left out a number of steps):

1) Granting that a personal God exists, it seems likely that such a deity would want to interact with sentient beings

2) such a deity would be capable of communicating with creation

3) such a deity would be capable of preserving that communication without error

Therefore, given the desire and capability of giving a communication to people without error, it becomes vastly more plausible, if not altogether certain, that the Bible is inerrant. Of course, if God does not exist–if we deny that there is a person deity–then it seems altogether impossible that an inerrant text could be produced on anything, let alone a faith system.

I consider this a positive argument because it proceeds from principles which can be established (or denied) as opposed to a simple assertion. It is not a matter of just presupposing inerrancy and challenging anyone who would take it on; instead it is a matter of arguing that God exists, desires communication with His people, and has brought about this communication without error. Although each premise needs to be expanded and defended on its on right, I ultimately think that each is true or at least more plausible than its denial. Christians who deny inerrancy must, I think, interact with an argument similar to this one. Their denial of inerrancy seems to entail a denial of one of these premises. I would contend that such a denial would be inconsistent within the Christian worldview.

Note that this argument turns on the issue of whether or not God exists. That is, for this argument to be carried, one must first turn to the question of whether God exists. I would note this is intentional: I do think that inerrancy is ultimately an issue which will be dependent upon and perhaps even derivative of one’s view of God.

Other Books

One counter-argument which inevitably comes up in conversations about an argument like this is that of “other books.” That is, could not the Mormon and the Muslim (among others) also make a similar case.

The short answer: Yes, they could.

Here is where I would turn to the evidence for each individual book. Granting a common ground that these claimed revelations–the Bible, the Book of Mormon, the Qu’ran, etc.–are each purported to be inerrant and that their inerrancy is more probable on a theistic view, which best matches reality? In other words, I would turn here to investigate the claims found within each book in order to see if they match with what we can discern from the world.

The argument I am making here is not intended to be a one step argument for Christian theism. Instead, it is an argument about the possibility of an inerrant work.

Appendix 1: Poythress and Inerrancy

Appendix 1: Poythress and Inerrancy

Vern Poythress provides an example of how this approach works. In his work, Inerrancy and Worldview (my review of this work can be found here), he continually focuses on how worldviews color one’s approach to challenges presented against inerrancy such as historical criticism, certain sociological theories, and philosophy of language. One example can be found in his discussion of historical criticism:

The difference between the two interpretations of the principle [of criticism] goes back to a difference in worldview. Does God govern the universe, including its history, or do impersonal laws govern it? If we assume the latter, it should not be surprising that the resulting principle undermines the Bible… It undermines the Bible because it assumes at the beginning that the God of the Bible does not exist. (Poythress, Inerrancy and Worldview

, 53, cited below)

Yet it is important to see that my approach here is different from that of Poythress. His approach seems to be largely negative. That is, he utilizes presuppositionalism in order to counter various challenges to the Bible. When a challenge is brought up to inerrancy, he argues that it of course stems from an issue of worldview. Although this is similar to my approach, Poythress never makes a positive argument for inerrancy, which I consider to be a vital part of the overall defense of the doctrine.

Appendix 2: Standard Presuppositionalism and Inerrancy

I would like to note that I am not attempting to claim that my defense of inerrancy here is the standard presuppositional approach. The standard presuppositional approach is much simpler: the apologist simply assumes the absolute truth and authority of God’s word as the starting point for all knowledge.

It should not surprise readers that, given this approach, most (if not all) presuppositionalists embrace the via negativa for defense of inerrancy. That is, the standard presuppositional defense of the Bible usually is reducible to merely pointing out how the attacks on Scripture stem largely from one’s worldview, not from the facts.

Thus, one of the foremost presuppositional apologists to have lived, Greg Bahnsen, writes:

[I]f the believer and unbeliever have different starting points [that is, different presuppositions from which all authority comes for the realm of knowledge] how can apologetic debate ever be resolved? [In answer to this,] the Christian carries his argument beyond “the facts…” to the level of self-evidencing presuppositions–the ultimate assumptions which select and interpret the facts. (Bahnsen, Always Ready, 72 cited below).

It should be clear that this standard presuppositional defense is therefore very different from what I have offered here. The standard presuppositional defense simply reduces the debate to “starting points” and attempts to show contradictions in other “starting points” in method, exposition, or the like. My defense has noted the vast importance of worldviews in a denial of inerrancy, but has also offered a positive defense of inerrancy. Yes, this defense turns on whether God exists, but that can hardly be seen as a defect or circularity in the argument.

Links

Like this page on Facebook: J.W. Wartick – “Always Have a Reason.” I often ask questions for readers and give links related to interests on this site.

The Presuppositional Apologetic of Cornelius Van Til– I explore the presuppositional method of apologetics through a case study of the man who may fairly be called its founder, Cornelius Van Til.

Debate Review: Greg Bahnsen vs. Gordon Stein– I review a debate between a prominent presuppositional apologist, the late Greg Bahnsen, and a leading atheist, Gordon Stein. It is worth reading/listening to because the debate really brings out the distinctiveness of the presuppositional apologetic.

Sources

Greg Bahnsen, Always Ready (Nacogdoches, TX: Covenant Media Press, 1996).

John Frame The Doctrine of the Word of God (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2010).

Vern Sheridan Poythress, Inerrancy and Worldview (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

If a Good God Exists: Presuppositional Apologetics and the problem of evil

It is clear that all things are ordered according to the perfect will of the Lord. If the Lord’s reasons for some state of affairs are inscrutable, does that mean that they are unjust? (Augustine, City of God

Book V, Chapter 2).

The problem of evil is the most pervasive argument used against Christianity. It also causes the most doubts among Christians. I know I can attest to crying out to God over the untold atrocities which continue to happen. Yet very often, I think, we are asking the wrong question. Here, I’ll explore the ways the problem of evil is presented. Then, I’ll offer what I think is a unique answer: the presuppositional response to the problem of evil. Finally, we’ll evaluate this response.

Two Ways to Present the Problem of Evil

The problem of evil is posed in a number of ways, but here I’ll outline two varieties.

The Classical/Logical Problem of Evil

God is said to be all powerful and all good, yet evil exists. Thus, it seems that either God does not want to prevent evil (in which case God is not all good) or God is incapable of preventing evil (and is thus not all powerful).

The Evidential Problem of Evil

Evil on its own may not prove that God does not exist (the logical/classical problem of evil), but it seems that surely the amount of evil should be less than what we observe. Surely, God is capable of reducing the amount of suffering by just one less child being beaten, or by one less tsunami killing hundreds. The very pervasiveness of evil makes it clear that no good God exists.

The Presuppositional Response to the Problem of Evil

One of the insights that we can gain from presuppositional apologetics is that it forces us to look at our preconceived notions about reality and how the impact our answers to questions and even the questions we choose to ask. The way that the problems of evil are outlined provides a prime example for how presuppositional approach to apologetics provides unique answers.

The presuppositional answer to these problems of evil is simple: If a good God exists, then these are not problems at all.

Of course, this seems overly simplified, and it is. But what the presuppositionalist is emphasizing is that the only way to make the two problems above make sense is to come from a kind of neutral or negative starting presupposition. The only way to say to construct the dilemma in the classical/logical problem of evil is to assume that there is not an all-powerful and all-good God to begin with. For, if an omnibenevolent, omnipotent being exists, then to say that God does not want to prevent evil seems false; while to say that God is incapable of preventing evil is also false. Thus, there would have to be a third option: perhaps God reasons for allowing evil are inscrutable; perhaps the free will defense succeeds; etc. Only if one assumes that there is no God can one make sense of the logical problem of evil to begin with.

The evidential problem of evil suffers an even worse conundrum given its presuppositions. For it once more assumes that God should do more to prevent evil, and so because God does not do more, God must not exist or must not care about evil. But who is to say that God should do more to prevent evil? Who is in a position to judge the overall evil in the world and say that there should be less? Furthermore, even assuming it were possible for there to be less evil, who knows the whole breadth of possible purposes God might have to allow for suffering and evil? The presuppositionalist agrees with the words of God in Job:

Who has a claim against me that I must pay?

Everything under heaven belongs to me. Job 41:11

The answer must come with humility: no one has such a claim. There is none who can claim that God owes them one thing. Yet this is not all an appeal to God’s sovereignty. Instead, it is an appeal to God’s goodness.

The late Greg Bahnsen, a defender of presuppositional apologetics, presents the presuppositional approach to the problem of evil in his work, Always Ready:

If the Christian presupposes that God is perfectly and completely good… then he is committed to evaluating everything within his experience in light of that presupposition. Accordingly, when the Christian observes evil events or things in the world, he can and should retain consistency with his presupposition about God’s goodness by now inferring that God has a morally good reason for the evil that exists. (171-172)

Thus, the strength that one assigns to the problem of evil ultimately depends quite a bit upon one’s presuppositions. If you believe you have good reason for thinking that God exists, then the problem of evil seems much less powerful than if you believe there is no good reason for thinking God exists.

Yeah… and?

Okay, so what’s the point? It may be that what we bring to the table does indeed alter our view of the problem of evil. Does that mean we are at a complete impasse? I think that this is where evidences come in, even on the presuppositional view. If all we have are presuppositions, then we are indeed stuck. But we must look at evidences to see whose presuppositions match reality. And, what we have done by centering the discussion of the problem of evil around presuppositions is to set it to the side. Surely the atheist would not suggest the Christian must abandon their presuppositions? It seems like a more rational perspective to look at the evidences. The presuppositionalist holds that when it comes to evil, it is really just a matter of presuppositions. If a Good God exists, we can trust God.

Links

The Presuppositional Apologetic of Cornelius Van Til– I explore the presuppositional method of apologetics through a case study of the man who may fairly be called its founder, Cornelius Van Til.

Debate Review: Greg Bahnsen vs. Gordon Stein– I review a debate between a prominent presuppositional apologist, the late Greg Bahnsen, and a leading atheist, Gordon Stein. It is worth reading/listening to because the debate really brings out the distinctiveness of the presuppositional apologetic.

I have explored this type of argument about the problem of evil before. See my post, What if? The “Job Answer” to the problem of evil.

I review Greg Bahnsen’s Always Ready.

Image credit: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Las_Conchas_Fire.jpg

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.