It is incredibly easy to fall victim to the idea that by reading just a few things on a topic by experts, you are suddenly an expert on the topic–or at least know enough to expertly comment upon it. There have even been studies on this and the eventual name given has been the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Biblical archaeology is absolutely one of those areas in which it is simple to get caught up in that problematical space between expert and one with no knowledge. In part, that’s because archaeology and historical study are such impossibly complex topics that even getting to the details of methodology can be daunting. Reading one take and moving on as if we have the facts is far easier.

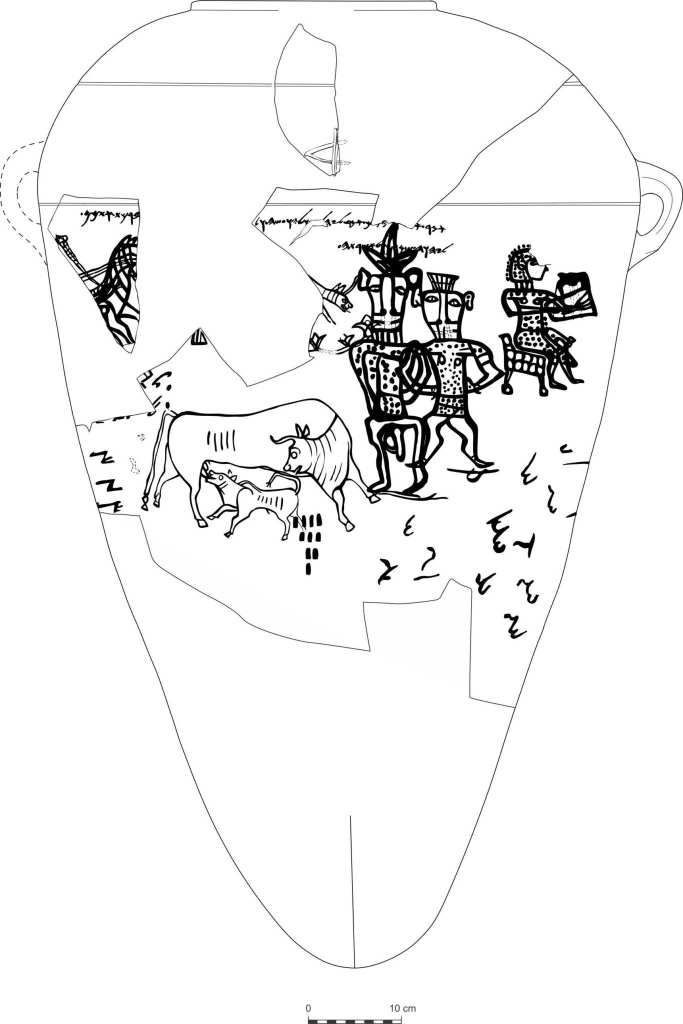

This was recently made clear to me personally when I encountered Theodore J. Lewis’s discussion of inscriptions found at Kuntillet Arjud in his book The Origin and Character of God. There, he notes that some scholars have seen “the female seated lyre player…” as a depiction of Asherah, accompanied by the text “Yahweh of Samaria and his asherah” ((a), 125). However, unlike Dever (discussed below) and others, Lewis notes that this is “inadvisable” because “There is no association of Asherah with music, nor would one expect to find the great mother goddess off center…” and the inscription and imagery likely “come from two separate times.” Additionally, this concept doesn’t account for there being three figures (ibid). Moreover, throughout this section, Lewis notes how difficult it is to parse the difference between asherah as a cultic symbol–an asherah pole or tree that was used in religious practices in Canaan–and citations related to Asherah the goddess, due to them being the same word. Indeed, it is difficult to even fully know whether such a distinction itself is valid.

By contrast, William G. Dever in his Beyond the Texts, cites the same find as depicting “two Bes figures and a half-nude female playing a lyre” ((c), 499). In a note, he argues that the depiction is a reference to Asherah as the goddess, not asherah as a cultic symbol, arguing that despite the missing possessive suffix, it is “graffiti” and so doesn’t need to apply all grammatical rules (ibid, n114, 543). He also argues that reading asherah as a cultic symbol in this inscription (and likely elsewhere) is reflective of “theological presuppositions” rather than the data (ibid).

This may seem a rather obscure fight to be having, but it is not. It would be indicative of at least some aspects of Israelite religion in the region if they saw Asherah as a divine consort of YHWH, something Dever argues elsewhere. However, Lewis does not see this same depiction as evidence of Asherah as YHWH’s consort, and Dever does not here suggest any reason for the third depicted figure (he apparently takes the figure next to the supposed YHWH figure as being Asherah, along with a third seated musician as a different figure).

Not only that, but Dever and Lewis’s approaches are markedly different related to how to treat archaeological and textual data more generally. Dever’s work’s name, Beyond the Texts, hints at his general approach, which he makes explicit therein–elevating archaeological data as perhaps just as significant as textual data. Lewis, however, notes repeatedly the difficulties inherent in using archaeological data to make points beyond the texts. One way this contrast can be seen is Lewis’s suggestion–backed by some scholars cited–that figurines found at archaeological sites should be seen as mortal–not divine–unless the figure being mortal is ruled out by some means (eg. a certain headdress known to be associated with a specific deity, see Lewis, 121ff).

I am by no means an expert in ANE material, archaeology, or historiography. I have studied each, including on master’s level courses, but only obliquely. This was another example that showed me how easy it is to be caught up in expert opinions. I read Dever first and found it utterly convincing, seeing the likelihood that in at least some times and places in ancient Israel, YHWH was likely depicted with a wife. Lewis, a work I’m still in progress of reading, seems to temper that expectation and conclusion somewhat. How do we know which to trust?

I think it is important to realize that as a non-expert, we don’t really need to have a firm opinion on this, in part because we don’t have the knowledge base to even do so. But it is important to be aware of our limitations. Additionally, it is important to realize additional limitations that both Lewis and Dever point out with both archaeology and texts. Archaeology is necessarily limited to what is found by archaeologists, which various studies suggest is an astronomically tiny percentage of all the material that might exist to be excavated. Additionally, the material that survives–even that not yet excavated, is only a tiny percentage of all the material of a culture. Not only were things reused and repurposed, but they were also destroyed, often intentionally. Thus, we are seeing only tiny parts of the true material culture of the ancient past. This applies to texts as well. There are untold numbers of texts forever lost to time that could give any number of clarification on so many fascinating topics. We should be thankful for what we can find, but realize that caution regarding conclusions is deeply important.

Regarding YHWH and Asherah–I don’t know. I think that some of this relies upon religious presuppositions, and I’m including Dever in on that. But I also think that there seems to be enough scattered evidence to suggest that there is some connection between the two. I’ll be interested to read the rest of Lewis’s book and see what he argues with the rest of the material about Asherah and asherah poles. For my readers here, I hope this can serve as a cautionary tale to be aware of how little we know, especially as non-experts.

That said, two things that are extremely clear are that: 1. the Biblical material itself shows evidence of religious development in Israel, and this can be extracted and shown alongside archaeological evidence; ancient Israel did not have a monolithic, exclusively monotheistic religion, though it seems the elites may have developed that and enforced it eventually; 2. there is so much more to the religion(s) of ancient Israel and the region that we have to learn, and certainly far more than the simplistic stories that we tend to learn in church. That doesn’t mean those simplistic stories are to be utterly rejected or seen as misleading or intentionally untrue; merely that there is, as almost always, more complexity than what we learned on a surface level.

Sources

(a) Lewis, Theodore J., The Origin and Character of God: Ancient Israelite Religion through the Lens of Divinity (New York, 2020: Oxford).

(b) Choi, G. (2016). “The Samarian Syncretic Yahwism and the Religious Center of Kuntillet ʿAjrud”. In Ganor, Saar; Kreimerman, Igor; Streit, Katharina; Mumcuoglu, Madeleine (eds.). From Shaʿar Hagolan to Shaaraim: Essays in Honor of Prof. Yosef Garfinkel. Israel Exploration Society.

Dever, William G., Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah (Atlanta, 2017: SBL).

SDG.

Discussion

No comments yet.