J.W. Wartick

“Only a Suffering God can help” – Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Theologia Crucis

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology is heavily based upon the Theologia Crucis or the Theology of the Cross which he inherited from Martin Luther. H. Gaylon Barker’s The Cross of Reality is a book-length exposition of this important aspect of Bonhoeffer’s theology that brings an enormous amount of material and analysis to bear.

Barker’s analysis of Bonhoeffer’s theology of the cross is worth quoting at length:

“One problem… religion produces , from Bonhoeffer’s perspective, is that it plays on human weakness. In the world in which people live out their lives… this means a disjuncture or contradiction. Daily people rely on their strengths, in which they don’t need God. In practical terms, therefore, God is pushed to the margins, turned to only as a ‘stop-gap’ when other sources have given out. Then God, perceived as a deus ex machina, is brought in to rescue people. This, in turn, leads to the religious conception of God and religion in general as being only partially necessary; they are not essential, but peripheral. All of this leads to intellectual dishonesty, which is not so unlike luther’s description of the theology of glory. The strength of the theology of the cross, on the other hand, is that it calls a thing what it is. It is honest about both God and the world, thereby enabling one to live in the world without seeking recourse in heavenly or escapist realigous practices. Additionally, such religious thinking leads to the creation of a God to suit human needs… For Bonhoeffer and Luther, however, the real God is one who doesn’t appear only in the form we might expect, one whom we can incorporate into our worldview or lifestyle. God is one who is always beyond our grasp, but at the same time is a hidden presence in the world” (394).

Barker highlights Bonhoeffer’s own words to make this point extremely clear:

“[W]e have to live in the world… [O]ur coming of age leads us to a truer recognition of our situation before God. God would have us know that we must live as those who manage their lives without God. The same God who is with us is the God who forsakes us (Mark 15:34! [“And at three in the afternoon Jesus cried out in a loud voice, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?‘ (which means ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’)”]). The same God who makes us to live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God, and with God, we live without God. God consents to be pushed out of the world and onto the cross; God is weak and powerless in the world and in precisely this way, and only so, is at our side and helps us. Matt. 8:17 [“This was to fulfill what was spoken through the prophet Isaiah: ‘He took up our infirmities and bore our diseases.’] makes it quite clear that Christ helps us not by virtue of his omnipotence but rather by virtue of his weakness and suffering!” [388, quoted from DBWE 8:478-479]

Thus, for Bonhoeffer, God is not there as the divine vending machine, there to send out blessings when needed or called upon due to human inability. Instead, God enters into the world and by suffering, alongside us, helps us.

Bonhoeffer put it thus: “Only a suffering God can help.” Bonhoeffer, seeing the world as it was in his time, during the reign of terror of the Nazis, imprisoned, knew and saw the evils of humanity. And he knew that in seeing this, theodicy would fail. A God who worked only through omnipotence and only where human capacities failed was a God that did not exist. Instead, the God who took on our suffering and came into the world, who “by viture of his weakness and suffering” came to save us, is the only one who acts in the world–in reality.

Only a suffering God can help.

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Freedom as an Essential Component of Biblical Research

James Barr (1924-2006) was a renowned biblical scholar who, in part, made some of his life’s work pushing back against fundamentalist readings of Scripture and Christianity. I have found his work to be deeply insightful, even reading it 40 or more years after the original publications. One insight I gleaned recently was from Holy Scripture: Canon, Authority, Criticism (1982). Here, he made a clear argument for the need for freedom in biblical scholarship:

“Research requires freedom of thought; if this is lacking, it only means that the research will be less good, in extreme cases that it will dry up altogether. Freedom is not something that should have to be wrung from a reluctant grasp: the church should promote freedom because freedom is part of its gospel. The same is true of theology: it is in the interests of theology itself that it should not seek the power to control and limit, that it should recognize, accept, and promote the fact that there are regions of biblical study for which the criteria of theology are not appropriate; just as it is salutary for the church that it should not seek to dominate the nature of education…

“THe relations between freedom and religion are paradoxical. Freedom of religion is one thing, freedom within religion is another. Freedom of religion is often thought of as freedom of religion from coercion through the state, and that can sometimes be very important, though it is far from being the nucleus of the idea of Christian freedom. Religions can demand freedom of religion, while denying freedom within religion, which is much closer to the idea of Christian freedom…” (109-110).

Note that the last line is saying that it is closer to Christian freedom to have freedom within religion than the opposite. Barr is saying that biblical and theological scholarship–and Christianity generally–benefits from freeing its scholars to explore whatever fields or ideas they deem necessary or of interest. For one, this is because freedom is part of Christianity’s gospel itself–a point Barr makes in passing. For another, this freedom will benefit Christianity because additional insight into its truths coming from even non religiously motivated research is of great use (a point he explores on 110-111).

Thus, limiting research by strict doctrinal codes is not desired even as such doctrinal codes, standard, or confessions are permitted to exist and sometimes even bolstered by research. But where research might push back on such codes, standards, and confessions, Christians ought to welcome it as something that might offer a corrective and exemplification of the gospel rather than as something to be shunned and feared.

SDG.

Book Review: “Triune Relationality: A Trinitarian Response to Islamic Monotheism” by Sherene Nicholas Khouri

Triune Relationality: A Trinitarian Response to Islamic Monotheism is more than a modern work of Trinitarian theology in conversation with Islam. Khouri brings centuries of historical conversations on this topic to light in a survey of the history of Trinitarian and anti-Trinitarian arguments between these two faiths. This, alongside an appeal to modern analytic theology and the argument that theology based upon the Greatest Possible Being must inherently be relational.

The first four chapters of the book work to survey the history of the Muslim-Christian dialogue on Christianity. Modern tools are brought to this analysis, but it also provides excellent background on the arguments involved. It is only in the final chapter that Khouri turns fully to modern Christian answers to Muslim anti-Trinitarian apologetics.

Any topic of this specificity requires engagement with seemingly obscure points, but readers interested in the topic will find it a wealth of information. Where mileage will vary is on how much readers adhere to the use of analytic theology and whether they believe that arguments for the Greatest Possible Being have a place in theology.

Triune Relationality is a challenging, informative read. People interested in Trinitarian theology and, specifically, how it might come into conversation with Muslim apologetics for absolute monotheism should check it out.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Walking Through Deconstruction: How to Be a Companion in a Crisis of Faith” by Ian Harper

Walking Through Deconstrution: How to Be a Companion in a Crisis of Faith by Ian Harper is a book not so much for people who are deconstructing but for Christians who know someone who is deconstructing and are struggling to know how to be a friend along the way. I read it as a Christian who has deconstructed (and, in case you have seen the tagline of this site, reconstructed) his faith. I think I can give at least some perspective to the contents from an insider and interested party.

I have to admit I had some healthy skepticism going into this book. The author has written for The Gospel Coalition, an evangelical reformed ministry that leans conservative [1]. There’s a Foreword from Gavin Ortlund, who is largely seen as an apologist who engages with and against… other Christians. I won’t apologize for that skepticism, but I am happy to report it was mostly misplaced.

Harper clearly acknowledges the many reasons why people deconstruct, while also making note of the trite, oft-wrong reasons that people offer to explain why other people deconstruct. Too often, Christians say things that suggest people only question Christianity because they want to lead a sinful lifestyle, or they downplay the real problems within Christianity by saying that the sins of individual people don’t make the central message untrue. You won’t find that in this book. Instead, Harper carefully notes that labels such as “good” or “bad” deconstruction–implying that a journey of faith can be categorized as such–are unhelpful. Additionally, he notes the many, many reasons people deconstruct and does so with an eye towards understanding rather than judging.

None of this is to say that Harper doesn’t still approach the problem from within a Reformed evangelical background. He clearly states that he believes human hearts are inherently sinful, and that deconstruction can be one thing that stems from that–despite having often good or at least understandable motivations (78-79). Another problem he cites is the need for individualism in our society (80ff). He notes that therapy “can” be a good thing, but that total reliance on therapeutic speech and activity can misplace true healing (83ff). This latter point is one that demonstrates Harper is attempting to walk along a very fine line. He doesn’t seem to want to say therapy is bad–and indeed says the opposite at times–but he also seems to want to say that we over-rely upon therapy and self-help and sees that therapy can become a replacement for religion (the latter point he makes explicit on p84). Intriguingly, he also notes that reliance on therapy alone can highlight class divisions as seeing a therapist is often a position of privilege (85). The over-reliance on devices that make promises about how we can now live is another factor Harper sees as contributing to deconstruction (88-89). In all of this, though, Harper seems to be seeking to make a point, which he ultimately brings home at the end of the chapter–that we humans have needs that we will meet in whatever way is available to us, and he sees the church as one way to meet some of those needs that should not be ignored (91).

The second part of the book focuses on Harper’s look at what it might mean to reconstruct faith and to assist in doing so as one of those “companion(s) in a crisis of faith” noted in the subtitle. Mileage on this section will vary wildly depending upon what readers themselves are looking to do and what their background beliefs are. Harper is again coming from a Reformed background, so his advice makes the most sense within that context. Even here, however, he makes several points that could carry beyond that specific set of beliefs. For example, he frames questioning of beliefs of Christianity as “what it feels like” vs. “what it is.” The former, he notes, people often see people’s questioning of faith as dipping into heresy when they are deconstructing and a goal of reconstructing towards orthodoxy. However, reality as he sees it is more aligned with deconstruction moving through beliefs that are unimportant to those that are important, urgent, or core, and then building back up from there (138-140). People move too quickly, sometimes, to judge others for heresy when it might be something else like ignorance or an attempt to reframe and discover core truths (ibid, cf also 141).

Walking Through Deconstruction isn’t perfect. No book is. But for a book for Christians to give other Christians about deconstruction, it is a solid choice. Unlike many books in this field that try to immediately say deconstructing Christians are trying to lead sinful lives or don’t want to conform to rules, Harper acknowledges the many reasons that people deconstruct and offers a way forward that isn’t entirely focused on trying to reconvert someone. Saying “you can do worse” is, at this point, honestly a good endorsement. There aren’t enough books that follow this path–trying to navigate both the realities of reasons why people deconstruct and still offer a way forward for staying faithful and being a faithful friend in that space. If nothing else, it is a very interesting and sometimes challenging read. Recommended reading.

Notes

[1] It’s worth noting that The Gospel Coalition has, at least, gone on record to push back against some far-right leaning Christians who have claimed, for example, that empathy is sinful. See, for example, the article “The Godliness of Empathy.” I would still take issues with some of the points made here, but this is a far cry from those claiming that empathy is somehow the path to sinful acceptance of anything.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“The Problem with Fundamentalism” according to James Barr

James Barr (1924-2006) is incredible to read as someone coming from a fundamentalist background. I’m reading his book The Scope and Authority of the Bible (1980) right now and it is so good. In one of the essays, “The Problem of Fundamentalism Today,” he writes:

“The problem of fundamentalism is that, far from being a biblical religion, an interpretation of scripture in its own terms, it has evaded the natural and literal sense of the Bible in order to imprison it within a particular tradition of human interpretation. The fact that this tradition… assigns an extremely high place to the nature and authority of the Bible in no way alters the situation described, namely that it functions as a human tradition which obscures and imprisons the meaning of scripture” (79).

Barr is an extremely gracious critic, as readers of this book will see–he bends over backwards to note fundamentalists still have good things to say about the Bible, for example–but his point is so incredibly valuable.

Conservative Christianity, while claiming to be solely biblical, has ‘imprisoned” the meaning of the Bible within its own logical and theological strictures. Fundamentalist Christianity is no more or less influenced by its cultural strictures than other forms, but takes enormous strides to avoid admitting that its attempt to read the Bible is conditioned by those lenses through which they read it. So they can claim their religion is “biblical” while the more liberal Christian might admit fully they’re reading the Bible through a lens and yet be more faithful to the text.

In the same essay, Barr notes that fundamentalism leads to difficulties with scholarship, too:

“The partisan light in which fundamentalists regard conservative scholarship itself corrupts the path which that scholarship may take. Partisan scholarship is of no use as scholarship: the only worthwhile criterion for scholarship is that it should be good scholarship, not that it should be conservative scholarship or any other kind of scholarship. And many conservative scholars realize this very well. Among their non-conservative peers they do not produce the arguments that fundamentalist opinion considers essential and they do not behave in the way that the fundamentalist society requires of its members.

“Fundamentalist apologists, exasperated, often ask me the question: but how can the conservative scholar win? Is not the balance loaded against [them]? The answer is: yes, he can win, but he can win only if he approaches the Bible… as a scholar of the biblical text” (74).

Time and time again, I have seen this play out. Some evangelical critique of their own apologists has gone down this line, noting that the engagement with non-evangelicals often takes a different tone and approach to the Bible than when it is an intra-conservative debate. And why? Because fundamentalist, evangelical interpretation itself is so culturally embedded that they cannot convince others on its own terms. This is yet another proof of Barr’s point above, that fundamentalism cannot make claim to being the sole biblical truth or even biblical at all when it is itself a culturally conditioned position to hold and interpret within.

The Scope and Authority of the Bible is proving as thought-provoking as any book I’ve read of late. This, despite it being more than 40 years old. I recommend Barr’s works quite highly.

SDG.

“Bonhoeffer and the Biosciences: An Initial Exploration” edited by Wüstenberg et al.

One of the wonderful things about burgeoning interest in Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s ethics, life, and theology is the way insights from him are being applied to an increasing number of fields and topics. Bonhoeffer and the Biosciences: An Initial Exploration edited by Wüstenberg, Heuser, and Hornung seeks to explore aspects of Bonhoeffer’s thought and life seeking insight from him in the realm of biosciences. What are the biosciences explored here? Topics like posthumanism, in vitro fertilization, abortion, ability and disability, and more are touched upon through the book.

The subtitle of “an initial exploration” is quite apt. The essays included here rarely provide what even feels like a rudimentary conclusion related to Bonhoeffer and biosciences. Instead, the essays are more akin to prompts for further exploration. And what prompts they are! Nearly every chapter brought numerous intriguing insights to bear and great scope for future research.

One example is in the discussion of genetic enhancement–what would this do to distributions of power and equality; what would enhancements mean about our desires; and how do we even make moral judgments about these (questions adapted from p.86)? Then there’s a chapter which ultimately calls for seeing caregivers and medical providers as being part of the “freedom for” the sake of the other (106-107). How could this help get applied to the Lutheran doctrine of vocation, which Bonhoeffer surely agreed with. “Caring for human life at its most vulnerable is… a practice that bears a unique promise: the promise to reconnect us with the truth and depths of our creaturely existence…” (106). Such insights are fascinating, and found throughout the book.

Bonhoeffer and the Biosciences: An Initial Exploration is a fantastic read, though it is one that leaves readers wanting more. Students of Bonhoeffer would do well to use it as a springboard for more discussion and exploration.

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Bonhoeffer’s Catechesis: Foundations for his Lutheranism and Religionlessness

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was deeply involved in educating youths. He saw the need for it and was apparently quite skilled, building a reputation in Barcelona for caring for a rambunctious group of students. When teaching at the illegal seminary at Finkenwalde, one of the many subjects he touched upon was catechesis–basic Christian education. Bonhoeffer’s teaching on catechesis revealed that his thoughts on religionless Christianity were already quite embedded at this middle stage of his theology, and that his staunch Lutheranism held throughout his life.

When starting his lectures on catechesis, he began with some commentary on Christian instruction. However, this commentary was fronted with the notion that Christian instruction is embedded in proclamation. Conceptually, this is because those involved in catechesis have been baptized, and, due to their baptism, they are already Christian. Thus, Bonhoeffer declares that, related to the education of young people: “the struggle, the victory belongs to the church because God has long since brought the children into the church through baptism. Whereas the state must first make itself master [Herr], the church proclaims the one who is Lord [Herr].” Bonhoeffer goes on to clarify, “Christian education begins where all other education ceases: What is essential has already happened. You have already been taken care of. You are the baptized church-community claimed by God” (DBWE 14:538).

Because of the status of those learning from the church as the already baptized, Bonhoeffer argues, the church can proclaim from the start the reality that they are already in the church community. Baptism has made this happen, by the power of the Spirit. It would be hard to imagine a more Lutheran understanding of the starting point of Christian instruction than this. For Bonhoeffer, baptism was not an abstraction or a symbol: it was a very real status change of the person being baptized as becoming part of the church-community.

The same lecture series shows Bonhoeffer’s thoughts on religionless Christianity were not merely a late development while in prison. While commenting on “What makes Christian education and instruction possible…” Bonhoeffer notes that it is “baptism and justification” (DBWE 14:539). This obviously hearkens back to the discussion above; baptism as a reality-changing sacrament. But he goes on: “People may well argue about whether religion can be taught. Religion is that which comes from the inside; Christ is that which comes from the outside, can be taught, and must be taught. Christianity is doctrine related to a certain form of existence (speech and life!)” (ibid, 539-540).

Bonhoeffer here links religion with that that comes from within–something he not-infrequently links to idol-building. Religion in his own time is what allowed the German Christian movement to join and overwhelmingly support the Reich Church of the Nazis. By contrast, Christ comes from the outside, through baptism, and can and must be taught. Our religious ways are attitudes we shape and create, but Christ, the God-reality, comes from outside of us and must be proclaimed. And, ironically, this leads to true foundations of doctrine that entail a “certain form of existence” which Bonhoeffer clearly links to the reality of everyday life but also to resistance and calls to repentance for the church itself.

In this way, we can see the foundations, at the least, are here in Bonhoeffer’s thought for religionless Christianity. The fact that there is a contrast between religion and Christ is quite evident. The link between Christ, word, and sacrament is fully there. So while some may claim Bonoheffer’s religionless Christianity is anti-ritual, this cannot be further from the truth. Here, Bonhoeffer very clearly links religionlessness to sacrament and true faith. For Bonhoeffer, what signifies religion is not traditions or sacrament, but rather that which comes from within us and causes us to create our idols.

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

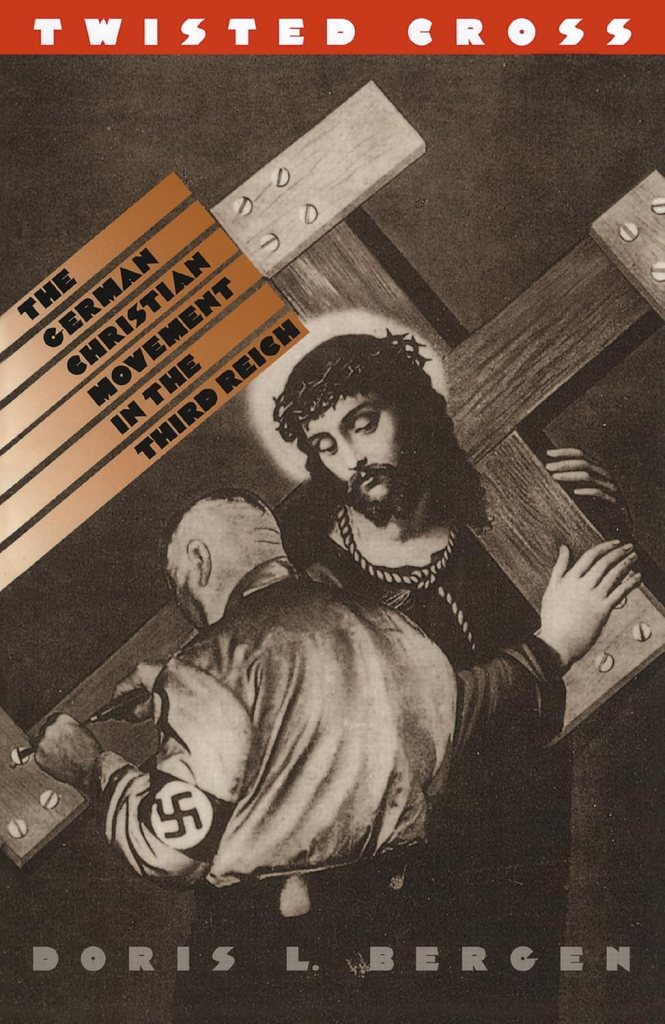

Now Reading: “Twisted Cross: The German Christian Movement inthe Third Reich” by Doris L. Bergen

“To me, the German Christian movement embodies a moral and spiritual dilemma I associate with my own religious questions: What is the value of religion, and in particular of Christianity, if it provides no defense against brutality and even can become a willing participant in genocide.”

Doris L. Bergen, Twisted Cross, Prologue

The German churches capitulated to Nazism. This is an historical fact. While there were notable exceptions–Dietrich Bonhoeffer is of special interest to me–the fact remains that a majority of Christians in Germany not only gave in but also willingly supported the Reich Church. In our own times in the United States, increasing calls for nationalism–not just patriotism–being united with Christianity provide eerie and alarming echoes of the same arguments used by the Reich-supporting German Christian movement.

Part of my studies with Dietrich Bonhoeffer include reading works about the times and places related to his work, and Twisted Cross: The German Christian Movement in the Third Reich by Doris L. Bergen is a work I am re-reading as part of that.

The cover image is an illustration by a German communist in 1933 who was opposing the unity of Nazism and Christianity. He, John Heartfield, wrote a few captions, including “The Cross Was Not Yet Heavy Enough.”

There’s a great quote from Bonhoeffer to lead it off: “Those who claim to be building up the church are, without a doubt, already at work on its destruction; unintentionally and unknowingly, they will construct a temple to idols.”

These questions resonate so much with me. Why has the church today seemingly chased after idols of power and prestige in the political environment? What does that say about the power (or powerlessness?) of Christianity and religion? I look forward to re-reading this book and seeking more answers.

SDG.

Book Review: “The Pursuit of Safety: A Theology of Danger, Risk, and Security” by Jeremy Lundgren

The Pursuit of Safety: A Theology of Danger, Risk, and Security by Jeremy Lundgren invites readers to delve deeply into concepts that seem quite simple on the surface–safety, protection, risk, security–and realize there is much more to these topics than might first seem obvious.

First, Lundgren dives into the concept of safety. What does it mean to have safety? What signs point us to feeling safe? Then, he goes through ways to analyze risk. Humanity has viewed risk differently at different points in history. Things that used to be risky are much “safer” now, but new risks have been introduced to deal with them. For example, travel across a continent is much safer than it used to be in any number of ways, but making such travel safe has introduced not just the risk of automobile accidents, but also has impacted the climate in negative ways. Humans don’t often realize the risks they are introducing while pursuing safety. These sections were insightful in many ways and certainly led to quite a bit of thought-provoking reflection later.

Next, Lundgren looks at ways humans have sought to avoid harm. Risk mitigation with the goal of zero accidents, for example, is pursuit of a goal that is both impossible and perhaps causes harms outside of safety that might not be worth the goal itself. The way we idolize technology looms large here, along with the many, many ways technology has actually made humanity open to new risks. Finally, Lundgren reflects on Christian discipleship and what it can mean to live as a Christian in a fallen, unsafe world. This last section includes the concepts of seeking to share news about Christ and what risks discipleship might lead to in the world.

One thing I thought was especially well done in the book was Lundgren’s bringing home of the realization that seeking safety does not always yield safety, and that mitigating risks can often lead to additional risks. Lundgren briefly cites Bonhoeffer in his discussion of discipleship and safety, but I wish he had gone further. Bonhoeffer has some fascinating words reflecting on peace and safety. He wrote that “peace must be dared” and refused to link peace with lack of bodily harm. I think this would have played well into Lundgren’s overall thesis.

The Pursuit of Safety rewards careful reading and reflection. Lundgren has written a formidable look at the concepts of safety and risk in Christian life, and it’s one that I think deserves serious study.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Harmonization of Scripture, Inerrancy, and History- Can inerrantists harmonize like historians?

John Warwick Montgomery has been hugely influential on my own faith life, including in my development of theology while disagreeing with some of what he says. When he passed last year, I wrote a brief in memoriam. Since then, I’ve been rereading works by him and about him. One such work is Tough-Minded Christianity, a collection of essays in honor of Montgomery that was published in 2009 [1].

One essay in the collection takes on James Barr’s work, Fundamentalism. Barr was an extremely well-respected Old Testament Scholar who launched many a fusillade against fundamentalism and, in particular, against fundamentalist readings of Scripture. In particular, Barr wrote about how inerrancy would not work as a way of reading the Bible, and he especially attacked such a reading as impossible given the Bible we already have. Irving Hexham’s essay, “Trashing Evangelical Christians: The Legacy of James’ Barr’s Fundamentalism” clearly takes issue with Barr’s approach. Hexham frequently writes about Barr’s work in derogatory terms, such as calling it a “propaganda tract,” among other things. But Barr was a deep enough scholar to prompt Hexham to try to refute some of his arguments, and in doing so, I think he actually shows where Barr is right and evangelical defenders of inerrancy are wrong.

Hexham seeks to defend fundamentalist attempts to harmonize apparent contradictions in the Biblical text. One such example that he cites is the attempt to harmonize the cleansing of the Temple in John 2 with the same account in Luke 19, Mark 11, and Matthew 21). Barr writes about how some have argued that the best way to harmonize these passages is to assert that Jesus cleansed the temple twice, once at the beginning of his ministry and again near the end of his ministry. Barr writes that this harmonization is “simple but ludicrous.”

Hexham, by contrast, takes extreme issue with the use of the term “ludicrous,” and argues instead that it’s not unreasonable to make such an attempt at harmonization because, after all, we don’t have complete historical records. Hexham skirts around Barr’s incisive critique of the same evangelicals also attempting to harmonize two ascension accounts by arguing one is literal and the other is telescoping by asserting that Barr is just wrong to think fundamentalists can’t use both literal and non-literal techniques to read the Bible. At issue, however, is not whether one can defend inerrancy of Scripture by mixing ways of reading it; the issue is instead whether such readings are plausible or even necessary to begin with.

A more powerful critique from Hexham is the note that historians do this kind of harmonization all the time. And this is an extremely vital point. Hexham writes, “Harmonization, far from being an unhistorical attempt to explain discrepancies, is precisely what most traditional historians do every time they discover conflicting accounts in the archival record.” He goes on to cite others who note that historians often have “no external evidence as to whether the event recorded happened once, twice, or even three times…” and that in almost any historical writing, a selection effect is occurring which means the authors are intentionally highlighting aspects of the narrative at hand.

It is true indeed that no author can comprehensively write every detail of anyone’s life, nor do the Gospels claim to be doing so for Jesus. I think it’s also largely true that historians are quite comfortable harmonizing different stories to make them make sense. Indeed, it would quickly become impossible to write or engage with history if, every time there was a discrepancy between accounts, one simply said the account was unreal or did not happen. But there’s a huge gap between conceding that point and conceding that therefore the historical documents can be considered inerrant. Indeed, the opposite seems to be true.

When historians are harmonizing differing texts about an event, they aren’t doing so with the assumption that either text is completely without error. This is a far cry from what evangelical/fundamentalist readers of Scripture have to do in order to harmonize texts. Once one holds a doctrine like inerrancy, in which the entire Bible is supposed to be completely free from error, the process of harmonization takes on entirely new difficulties. One cannot, as historians do, harmonize two passages by simply stating one is mistaken. If one document says an event occurred at 14:00 and the other says it occurred at 04:00, the historian can do many things, such as find another source that might confirm one and deny the other. But the inerrantist cannot do that. They must come up with a harmonization that not only brings two passages together, but also makes them both somehow emerge from the harmonizing completely unscathed. And that is where things start to become absurd. Because for the inerrantist, the only way to harmonize the two times for the same event above is to multiply the event. After all, the times cannot be wrong; admitting one of the times is wrong is to admit an error into the text. Therefore, the event itself must have occurred at both times. And that is what Barr is getting at with his critique of fundamentalists readings as being ludicrous.

Certainly one may punt to the broad possibility that we don’t have the Bible telling us that a cleansing of the temple only occurred one time, but every indication seems to be that such an event was unique and powerful, not something that Jesus decided to do, say, every Tuesday or so. The ascension is even more absurd to multiply, which is what leads the inerrantist to suddenly abandon their attempt to read the historical narrative as historical reportage and instead read it as a telescoping timeline. That’s the only way to salvage the text–by turning it into something that is intentionally not reporting things in the exact timeline in which they occurred.

Hexham’s attempt to salvage inerrantist harmonization methods, then, fails. While it is still remotely possible that some events happened twice, allowing there to be a direct, historical reporting happening in both instances of an event; such a broad possibility is not all that matters. Not every harmonization can be achieved by simply multiplying instances of the event occurring. And no historian is attempting to harmonize other historic texts by assuming they are entirely without error. The parallel Hexham attempts to draw upon is undermined by his own prior commitments. Inerrantists aren’t mashing two texts together by using other sources to determine their accuracy or looking at the plausible explanations. No, they are absolutely committed to the assumption that any two (or more) Scriptural passages they are trying to harmonize are entirely without error, and therefore any harmonization must preserve that central assumption. There’s a vast chasm between those two methodologies, and one that makes the inerrantist reading seem, at times, ludicrous.

Notes

[1]It’s remarkable looking at the book now, with its foreword by Paige Patterson, who has since been implicated in covering up sexual abuse (see here), an essay by Ravi Zacharias (multiple allegations of sexual abuse here), and thinking about how highly touted this book was at the time. In apologetics circles, I remember seeing a lot of discussion, though I’ve rarely seen it mentioned since about 2014. This might be, in part, due to JWM not being as well-loved in those circles as some other apologists. In any case, this collection purports to carry on JWM’s “tough minded” approach to Christianity, one built upon strength of evidence and an apologetic approach of the same.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.