theology

“The Journey of Modern Theology: From Reconstruction to Deconstruction” by Roger E. Olson – An epochal work of theological history

The Journey of Modern Theology: From Resconstruction to Deconstruction by Roger E. Olson is a monumental achievement of theological analysis and history.

The book is focused around modernity and the theology inspired from it, opposed to it, and moving with, against, and towards it. It is roughly divided chronologically and topically, with each chapter denoting an era of theological development and highlighting various theologians involved in that development. Olson’s accounting is largely neutral and fact-based reportage–he is informing readers on what the various theologians taught and believed rather than providing an analysis thereof. However, many of the major thinkers’ sections include a small section on contemporaneous critiques and responses.

Olson starts off with a brief overview of modernism and modernity, showing the scientific and cultural revolutions often associated with it. Then, he moves to various chapters analyzing modernist theologians and thinkers. Theologians given overviews include (but are not limited to): Friedrich Schleiermacher, Albrecht Ritschl, Karl Barth, Horace Bushnell, Paul Tillich, Jurgen Moltmann, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Hans Kung, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Charles Hodge, Stanley Hauerwas, Reinhold Niebuhr, Ernst Troeltsch, and many, many more. Chapters include: “Liberal Theologies Reconstruct Christianity in Light of Modernity,” Mediating Theologies Build Bridges Between Orthodoxy and Liberalism,” Theologians Look to the Future with Hope,” etc.

The chapter headings give broad brush introductions to the topics at hand. As I said above, these chapters are roughly chronologically based, though there is plenty of overlap. Olson organizes these around movements, showing the warp and weft movement of theology throughout the modernist period into the postmodern one. Again almost all of the analysis is fact based reportage–here’s what Schleiermacher wrote and believed–sometimes accompanied by a section of “here’s what Schleiermacher’s critics said.” Olson only really tips his hand in the conclusion, showing where his own views lie. As such, that makes the book an incredibly valuable work to simply learn about modernist theologians and theological movements. There were many times I found myself pursuing a thread of thought outside the bounds of the book, getting an interlibrary loan from an author I hadn’t read before, or researching more online.

The value of a book like this can’t really be understated. It is a must have for readers interested in theological history and knowing where and how a lot of current theology came from. Additionally, students of theology can find within it many guidelines for further research and avenues to explore. Are you interested in a theology of liberation? There’s a brief summary here that names names and shows where the thought process is going. Want to know about conservative development related to modernist thought? Those thinkers are here, too. Whether orthodox or not; intentionally or not; Olson does an incredible job across the board giving readers much to learn and contemplate.

The Journey of Modern Theology is a fantastic read that will give readers many, many avenues of further research alongside a baseline understanding of the origins and development of theology alongside and against modernism. Highly recommended.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Inerrancy Undermines Interpretive Method?

James Barr’s work, Fundamentalism (1977) remains incredibly relevant to this day. I have been reading through it and offering up thoughts as I go. I’m reading the chapter about the Bible and Barr has enormous insight into the Fundamentalist (and here it is okay to substitute in “Evangelical”) reading of the Bible.

I’ve already written about how Barr notes that fundamentalists do not have a consistent hermeneutic of the Bible because their adherence to inerrancy forces them to read passages in light of their own understanding of truth. Barr isn’t done firing his salvoes at this issue, though he also notes that many people misread fundamentalists on their use of literalism:

“It is thus certainly wrong to say… that for fundamentalists the literal is the only sense of truth. Conservative apologists are right in repudiating this allegation. Unfortunately, the truth is much worse than the allegation that they rightly reject. Literality, though it might well be deserving of criticism, would at least be a somewhat consistent interpretative principle, and the carrying out of it would deserve some attention as a significant achievement. What fundamentalists do pursue is a completely unprincipled – in the strict sense unprincipled, because guided by no principle of interpretation – approach, in which the only guiding criterion is that the Bible should, by the sorts of truth that fundamentalists respect and follow, be true and not in any sort of error” (49).

Here Barr notes first that fundamentalists/evangelicals are right to push back against the accusation that they simply see literalism as the only way to read the Bible. However, he goes on to point out that their approach is significantly more problematic, because they eschew all principles of interpretation other than the one that the Bible should not be found to be in error on any point.

Who determines how to interpret any given passage, then, and how? Pontius Pilate asked “what is truth?” and has been lampooned time and again–but the question could be posed to conservative readers of Scripture, who, in their attempts to define truth, go to extraordinary lengths to massage the word into what they need it to mean to preserve the Bible (the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy is full of this). Who determines what is an error?

In my own life, I experienced this unprincipled–again, using the word technically as meaning literally without principle–approach to reading the Bible. At a Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod college, I was taught that we needed to use certain principles of interpretation, specifically those following a supposed “historical grammatical” method of interpretation. This method, among other things, aims at attempting to find the authors’ original intent in meaning in the Biblical text. Yet, when I pointed out that our knowledge of the thinking of the Ancient Near Eastern world meant that interpreting the passages which depict a flat earth with four corners seem to be the right interpretation, I was told that we suddenly didn’t follow a method that went to the authors’ original meaning. Another pastor told me very specifically that we couldn’t know the authors’ original intent in writing the words of Scripture, but the same pastor later countered my doubting of young earth creationism by claiming that the author of Genesis knew the Earth was young–and so intended us to believe so as well.

The shifting sand of interpretation would seem entirely odd if it wasn’t placed in the context of inerrancy, which is the tail that wags the dog. All conservative interpretation now centers itself around this new doctrine. Reading books about the Canaanite conquest from conservative scholars is telling in this regard, as are questions about exactly what happened with certain miraculous events in the Bible. The debates often center around just how far one can push inerrancy without it breaking. Can one say that the walls of Jericho didn’t literally fall to pieces after being marched around and shouted at a certain number of times and still hold to inerrancy? It seems silly, but this is a real debate that is happening in literature right now. The same question is asked, time and again, for any number of things–whether Jonah was really swallowed by a fish (or a whale?)–whether one has to affirm Job was a real person to affirm inerrancy. The questions in evangelical and conservative scholarship related to the Bible are so often not about what the text is actually teaching us but rather on what exactly is allowed to be said in the context of inerrancy. And when someone does do some serious hermeneutical work that pushes at a supposed boundary of inerrancy, they are inevitably called to account in conservative academic journals.

Inerrancy controls the narrative, it controls the hermeneutic, and it strangles the interpretation of the Bible. It ought to be abandoned.

Fundamentalism continues to provide fruit for thought, almost 50 years after its initial publication. I highly recommend it to readers.

SDG.

Freedom as an Essential Component of Biblical Research

James Barr (1924-2006) was a renowned biblical scholar who, in part, made some of his life’s work pushing back against fundamentalist readings of Scripture and Christianity. I have found his work to be deeply insightful, even reading it 40 or more years after the original publications. One insight I gleaned recently was from Holy Scripture: Canon, Authority, Criticism (1982). Here, he made a clear argument for the need for freedom in biblical scholarship:

“Research requires freedom of thought; if this is lacking, it only means that the research will be less good, in extreme cases that it will dry up altogether. Freedom is not something that should have to be wrung from a reluctant grasp: the church should promote freedom because freedom is part of its gospel. The same is true of theology: it is in the interests of theology itself that it should not seek the power to control and limit, that it should recognize, accept, and promote the fact that there are regions of biblical study for which the criteria of theology are not appropriate; just as it is salutary for the church that it should not seek to dominate the nature of education…

“THe relations between freedom and religion are paradoxical. Freedom of religion is one thing, freedom within religion is another. Freedom of religion is often thought of as freedom of religion from coercion through the state, and that can sometimes be very important, though it is far from being the nucleus of the idea of Christian freedom. Religions can demand freedom of religion, while denying freedom within religion, which is much closer to the idea of Christian freedom…” (109-110).

Note that the last line is saying that it is closer to Christian freedom to have freedom within religion than the opposite. Barr is saying that biblical and theological scholarship–and Christianity generally–benefits from freeing its scholars to explore whatever fields or ideas they deem necessary or of interest. For one, this is because freedom is part of Christianity’s gospel itself–a point Barr makes in passing. For another, this freedom will benefit Christianity because additional insight into its truths coming from even non religiously motivated research is of great use (a point he explores on 110-111).

Thus, limiting research by strict doctrinal codes is not desired even as such doctrinal codes, standard, or confessions are permitted to exist and sometimes even bolstered by research. But where research might push back on such codes, standards, and confessions, Christians ought to welcome it as something that might offer a corrective and exemplification of the gospel rather than as something to be shunned and feared.

SDG.

“The Problem with Fundamentalism” according to James Barr

James Barr (1924-2006) is incredible to read as someone coming from a fundamentalist background. I’m reading his book The Scope and Authority of the Bible (1980) right now and it is so good. In one of the essays, “The Problem of Fundamentalism Today,” he writes:

“The problem of fundamentalism is that, far from being a biblical religion, an interpretation of scripture in its own terms, it has evaded the natural and literal sense of the Bible in order to imprison it within a particular tradition of human interpretation. The fact that this tradition… assigns an extremely high place to the nature and authority of the Bible in no way alters the situation described, namely that it functions as a human tradition which obscures and imprisons the meaning of scripture” (79).

Barr is an extremely gracious critic, as readers of this book will see–he bends over backwards to note fundamentalists still have good things to say about the Bible, for example–but his point is so incredibly valuable.

Conservative Christianity, while claiming to be solely biblical, has ‘imprisoned” the meaning of the Bible within its own logical and theological strictures. Fundamentalist Christianity is no more or less influenced by its cultural strictures than other forms, but takes enormous strides to avoid admitting that its attempt to read the Bible is conditioned by those lenses through which they read it. So they can claim their religion is “biblical” while the more liberal Christian might admit fully they’re reading the Bible through a lens and yet be more faithful to the text.

In the same essay, Barr notes that fundamentalism leads to difficulties with scholarship, too:

“The partisan light in which fundamentalists regard conservative scholarship itself corrupts the path which that scholarship may take. Partisan scholarship is of no use as scholarship: the only worthwhile criterion for scholarship is that it should be good scholarship, not that it should be conservative scholarship or any other kind of scholarship. And many conservative scholars realize this very well. Among their non-conservative peers they do not produce the arguments that fundamentalist opinion considers essential and they do not behave in the way that the fundamentalist society requires of its members.

“Fundamentalist apologists, exasperated, often ask me the question: but how can the conservative scholar win? Is not the balance loaded against [them]? The answer is: yes, he can win, but he can win only if he approaches the Bible… as a scholar of the biblical text” (74).

Time and time again, I have seen this play out. Some evangelical critique of their own apologists has gone down this line, noting that the engagement with non-evangelicals often takes a different tone and approach to the Bible than when it is an intra-conservative debate. And why? Because fundamentalist, evangelical interpretation itself is so culturally embedded that they cannot convince others on its own terms. This is yet another proof of Barr’s point above, that fundamentalism cannot make claim to being the sole biblical truth or even biblical at all when it is itself a culturally conditioned position to hold and interpret within.

The Scope and Authority of the Bible is proving as thought-provoking as any book I’ve read of late. This, despite it being more than 40 years old. I recommend Barr’s works quite highly.

SDG.

Learning about Reformation History: “Melanchthon: The Quiet Reformer” by Clyde L. Manschreck

I have long wondered about Philip Melanchthon. He seemed to get vilified in a lot of Lutheran circles I ran in, but he also was clearly at the forefront of Lutheran theology at the time of its formation. Luther rarely seemed to have said anything negative about Melanchthon, but the charge was that he turned away from Lutheranism later in his life and compromised. Enter Clyde L. Manschreck’s excellent biography, Melanchthon: The Quiet Reformer. Manschreck presents a fascinating, balanced perspective on Melanchthon, one of the most intriguing of Reformation persons.

Manschreck starts off, appropriately enough, with looking at how Melanchthon has been treated historically. Surprisingly few biographies exist of the Reformer, especially compared to other luminaries of the period who had less of an impact. After his death, there was criticism from three fronts: he was too Lutheran for Catholics, too Calvinist for Lutherans, and too Catholic for Calvinists. That’s oversimplifying it a bit, but it becomes clear that his legacy was marred by attacks from all sides. So who was the man, and what did he really believe–and was he an infamous compromiser?

Manschreck moves very swiftly past Melanchthon’s early life, almost immediately settling into the time that brought him to Wittenberg. But as Manschreck paints the picture of Melanchthon’s time there, first as an extraordinary lecturer with phenomenal skill and later as a Reformer, we also get deep insight into his character and beliefs. Melanchthon, like many early Lutherans (and a huge amount of the surrounding population) believed in astrology. It’s a strange thing when you look back on it, but it was conceived as a kind of science. Melanchthon was a firm believer, even lamenting the sign a child-in-law was born under when he came to dislike them. Melanchthon also was a champion for public schools, creating the first publicly funded schools across Germany, and advocated for (and got) living wages for teachers. His reasoning was that if a teacher had to work yet another job to just be able to eat or live, the wouldn’t be able to focus on bettering their mind and, in turn, their students’ minds.

Melanchthon and Luther hit it off almost immediately, and Melanchthon joining the Reformation was an organic thing, rather than something one can just point to a single moment as the moment of changing of heart. He clearly believed in the arguments of justification, and ultimately became one of the primary (or the primary) authors of much of the Lutheran Confessions. Setting the writing of these alongside the circumstances in which they occurred makes them more understandable. The Augsburg Confession being prepared to try to, in part, make it clear that their movement wasn’t heretical and could be defended on Scriptural grounds is a fascinating story. Additional clarification due to attempts to unite with other Reformers–attempts that ultimately failed with Zwingli and Calvin–is also set in its historical perspective. The writing of the Confessions should not be separated in understanding from their historical circumstances.

Fascinating historical details about Melanchthon’s life can be found in abundance. Did you know that he had no small amount of correspondence with Henry VIII? The latter desired Melanchthon’s comments on his marriage, hoping the Reformer might be open to giving him an out. Even when Melanchthon failed to deliver for Henry VIII, the King realized the political expediency of an alliance and, perhaps, even was swayed ever so slightly towards some Protestant points. Manschreck makes it clear Henry VIII’s interest was almost certainly political–how to get out of an undesired marriage in a desirable way.

Ultimately, Manschreck paints Melanchthon as a man of convictions who was willing to change his beliefs as he learned more. One of the most obvious examples was Melanchthon’s shift towards a kind of spiritualized view of real presence regarding the Lord’s Supper. What’s interesting with this is that Manschreck is able to document that Luther was aware of this shift and yet explicitly did not condemn it, despite multiple means and opportunities to do so. Was it out of respect for Melanchthon? Or was it a recognition that Melanchthon’s position was somewhere within the Lutheran fold (a fold that is anachronistic to apply to the situation anyway)? I don’t know, but it is worth reading the whole account, including Luther’s non-condemnation. Perhaps Melanchthon could be somewhat welcomed back into Lutheran teaching on some level? Again, I know not. But what’s clear is that Melanchthon sought to go back to the source (the ad fontes of the Reformation and Renaissance) and to understand Scripture’s teaching without trying to invent new doctrines.

Melanchthon: The Quiet Reformer is a superb biography that is well worth the read by any wishing to learn more about one of the most important figures of the early Reformation. I found it informative, balanced, and of interest to even broader world events.

Links

Reformation Theology– Check out all my posts on various topics related to the Reformation (scroll down for more).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“The Foolishness of God” by Siegbert W. Becker- An engaging struggle

Many years ago, when I was deep into apologetics and trying to figure out my place in the world and in my faith, my dad gifted me with a copy of The Foolishness of God: The Place of Reason in the Theology of Martin Luther by Siegbert W. Becker. Well, a lot has changed since then, and I am still trying to figure out my place in the world and in my faith, but I am much more skeptical of apologetics than I was then… to say the least. I re-read The Foolishness of God now, probably more than a decade after my original reading. It was fascinating to see my scrawling notes labeling things as ridiculous or wrong when I now basically think a lot of it is right. On the flip side, I still have quite a bit to critique. I’ll offer some of my thoughts here, from a viewpoint of a progressive Lutheran.

Becker starts by quoting several things Luther says about reason, from naming it “the devil’s bride” to being “God’s greatest and most important gift” to humankind (1). How is it possible that reason can be a great evil, vilest deceiver of humanity while also being one of the most enlightening parts of human existence? One small part of Luther’s–as Becker interprets him–answer is that it depends on what reason is being used for. That’s a simplistic answer, though, suggesting one could categorize things like nature and science (reason is good!) and judging biblical truth (reason is bad!) into neat boxes for Luther. In some ways, this can be done; but in others, when one digs more deeply, it becomes clear that such an application would be an okay rule of thumb for reading Luther but would not be accurate all the way through. For example, where Luther sees the Bible teaching directly on nature or science, using reason to judge that teaching would be rejected. This, of course, opens up my first and probably greatest point of disagreement with Luther’s theses about reason. And yet, it also is confusing, because in some ways I’m not sure I wholly disagree.

What I mean by this is that I, too, am skeptical of the use of human reason for any number of… reasons. This is especially true when it comes to thinking about God. Supposing it is true that there is a God and that God is an infinite being in any way–whether it is infinitely good, infinitely powerful, etc. In that case, it seems that to suggest that we can use reason to grasp things about God is a fool’s errand. We are not infinite and can certainly not grasp the infinite; how can we expect our brains that cannot contain the multitudes to reason around God? On the other hand, in many ways reason is all we have. Even supposing God exists, we ultimately act or believe in ways and things we think are reasonable. And I’m deeply skeptical of a denial of this. What I mean by the latter is that I simply do not believe that people can believe things they think are inherently anti- or irrational. Becker outright makes the claim that Luther–and presumably Becker himself–do believe such things. Time and again, Becker flatly states that some claims of Christianity are inherently contradictory–be it the Trinity, the Incarnation, or [for Lutherans] Christ’s presence in the Lord’s Supper. So Becker is claiming that Luther truly did believe in things he thought were inherently anti-reason and irrational. But when push comes to shove, I strongly suspect that Luther and people like him who make these claims think that it imminently reasonable to believe in the irrational. Even while claiming that they believe in things they claim they think are contradictory, they are doing so because it makes sense to them. And this is precisely because of the limitations of human reason and thinking. We cannot go beyond our own head, we have to go with what we think is right, perhaps even while claiming we think it is irrational to do so.

Setting aside that question, Luther’s solution to the gap between the finite and the infinite is that of revelation. Because God became incarnate and came to humanity, we, too, can know God. God revealed God to us. Becker rushes to use this to attempt to counter what he calls Neo-orthodox interpretations that stack the Bible against Christ. He writes, “Neo-orthodoxy’s distinction between faith in Christ and faith in statements, or ‘faith in a book,’ is artificial and contrary to reason. By rejecting ‘propositional revelation’ and making the Bible only a ‘record of’ and ‘witness to’ revelation, the neo-orthodox theologians drain faith of its intellectual content” (11). I find this deeply ironic wording in a book that later has Becker outright claiming that Luther–and by extension Becker himself–believed things that are contrary to reason and affirming that this is a perfectly correct (we dare not say “reasonable”) thing to do. In my opinion, at least, it is quite right to make the distinction between faith in Christ and faith in statements. That doesn’t mean the Bible is devoid of revelation or can have no revelation; rather, it means that, as Luther put it [paraphrasing here], the Bible is the cradle of Christ. But to put the Bible then on par with Christ as a similarly perfect revelation is to make a massive mistake, as people, including Lutherans like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, have argued.

All of this might make it seem I have a largely negative outlook on Becker’s work. Far from it. I found it quite stimulating and generally convincing on a number of points. Most of it, of course, is exegesis of Luther’s own views of reason. And I think that Luther, while he could stand to be far more systematic and clear, makes quite a few excellent points about reason. When it comes to trying to draw near to God, reason does not do well. Why? Our own era has so many arguments in philosophy of religion about the existence of God. Anyone who has read or engaged with the minutiae of analytic theology or analytic philosophy getting applied to God has experienced what I think, in part, Luther was warning against. Philosophers, apologists, and theologians continue to attempt to plumb the very nature of God and gird it up with scaffolds of reason, providing any number of supposed arguments for God’s existence, proofs of Christological points, and the like. Bonhoeffer, a favorite theologian of mine, put many of these attempts to shame in a succinct quote: “A God who could be proved by us would be an idol.”

I think a similar sentiment applies to so much about God and even just the universe. I mean, we’re on a planet that is less than a speck in a cosmos that is so unimaginably huge and ancient that thinking we can comprehend it is honestly shocking. Sure, we can slap numbers on it, using our human reason to try to slice the universe into chewable bites, but when we find out things like how it takes more than 1 million Earth’s to fill the Sun, and that our Sun isn’t even remotely the largest star, nor the largest solar system, etc… how absurd is it to think we really comprehend any of it? And so, for me, from a very different angle, Luther’s words about reason make sense. Sure, we can use it to try to understand little slices of nature. But when we start to line it up with things of the infinite, it may be better to just let God be God.

The Foolishness of God is a fascinating, engaging, and sometimes frustrating work. In a lot of ways, it’s like engaging with Luther’s own works. It’s not systematic; it doesn’t cohere; it’s intentionally provocative. I will likely give it another read one day, and who knows where I–and it–shall stand?

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Genesis as History- Some difficulties

Zondervan’s Counterpoints Series brings together different views on various theological subjects to compare and contrast them. The series has varying success, often not representing even the full gamut of even Evangelical views on a topic or even misrepresenting orthodox views from other traditions[1]. Here, in Genesis: History, Fiction, or Neither? Three views on the Bible’s Earliest Chapters, we see another example of failing to include a whole range of views on a topic. Obviously this has to be at least partially an editorial choice, as representing thousands of years and hundreds of views on the earliest chapters of Genesis would be impossible in any single book. On the surface it seems to provide all the options, but even within the text of the book, the struggle over labeling something as “myth” and what that means for history persists. Outlining all of the problems in attempting to classify Genesis as straightforward history would be a monumental task, but here I want to use James K. Hoffmeier’s chapter as a case study in some of the difficulties with taking Genesis as “history.”

Hoffmeier has the unenviable task of attempting to turn Genesis 1-11 into “history.” One obvious question, then, is “What is history?” As someone who has a major interest in history and historiography, defining history is… quite difficult. Even basic assumptions about what is meant by history are questioned in the academic literature on the topic. This isn’t because academics are trying to be difficult, but rather because human endeavors are rarely simple, and an attempt to write about or describe those endeavors in the past just adds layers upon layers to that complexity. For example, is it the case that someone writing a text of history is trying to tell the reader what “really happened”? On its face, the answer seems to be yes, but that is often not the case. In ancient times, acts of writing about the past often had meaning behind them. A simple act of creating a genealogy might have the intent of linking one ruler to another who had previously had no connection. We in fact see this in Ancient Near Eastern genealogies, when we find that they often move kings in and out of lists and find new fathers for legitimizing current or past rulers. In our own time, we can see the bias inherent in writing on certain topics. The simple description of history as the attempt to write down what “really happened” is just that- simple to the point of being overly simplistic. History is rarely just an attempt to write what actually occurred, and the connection between our time and the past is often less straightforward than one might think.

All of this is to say that it is somewhat astonishing to me to see that there is almost no attempt to define history either by the editor of this volume or by Hoffmeier. Reading an intent onto such an act is folly, but the lack of attempting the definition certainly makes the whole endeavor squishier. Namely, it allows one defending the concept of Genesis as “history” to simply hand wave at a generalized idea of what history is when they are challenged on specific points (more on this later).

Hoffmeier’s defense of Genesis as history is necessarily short based on the nature of the work, but it gives us some interesting avenues to pursue. He specifically cites some case studies to show that Genesis is intended as history. First, he looks at the Garden of Eden. After simply stating that the talking snake, the forming of Eve from Adam’s rib (a likely mistranslation anyway with some, erm, lively interpretive attempts), etc. are tied to “myth,” he quickly states that “the author of the narrative goes to great lengths to place Eden within the known geography of the ancient Near East…” (32). Hoffmeier’s argument moves on to show that there are four rivers that are named and that other geographic details are presented in order to help the reader geographically locate the Garden. Remarkably, simply because of these geographic details, Hoffmeier concludes, “though the garden pericope may contain mythic elements, it is set in ‘our historical and geographical world,’ which is hard to reconcile with pure mythology” (35).

I find this an entirely inadequate defense of this story as history. Ben Hur by Lew Wallace takes place in our historical and geographical world and contains mythical elements, but can hardly be construed as history. Similar things could be said for any number of alternative histories. Indeed, one could make the same vague conclusion about the Harry Potter series! It has identifiable places and often goes to great lengths to tell readers where they are in the world. As a parallel to Hoffmeier’s difficulty in locating some of the rivers mentioned around Eden, perhaps the location of Privet Drive, Harry Potter’s boyhood home, could serve–something intended as sounding like a place, but impossible to locate on a map. The stories contain mythical elements, but we can hardly dismiss them as “pure mythology,” right? After all, they’ve got place names! Similar things could be said for Percy Jackson or even the Chronicles of Narnia! It is astonishing that simply having some geographical details is seen as evidence to suggest the contents of a story is intended to be accurately describing things that actually happened.

Hoffmeier’s defense of the historical nature of Genesis 6:1-4–a story rife with literary, theological, and textual questions–is even more vague. Here, he notes several of the problems with figuring out who the Nephilim are, argues for some parallels with Babel, and then when it comes time to show that it is history simply appeals to a theological point, not an historical one! He writes, “I contend that despite our inability to completely understand this short episode, it must recall a genuine memory from early human history; after all, it is held up as the ‘final straw’ that caused God to determine to judge creation [and send a Flood]… For God to resolve to wipe out humans on the earth would surely not be the result of some made up story!” (41).

There’s a lot we could unpack here, from the assumption that the Flood narrative is global and actually wiped out all humans on Earth to the fact that Hoffmeier essentially concedes that this allegedly historical narrative is confusing enough that we can’t really understand what’s happening. But instead of unpacking all of that, I want to focus simply on his defense. His entire defense of this as historical is wrapped up not in features of the text itself, not in any archaeological or paleontological finds to back it up; no, it is based upon a theological argument from incredulity! If we assume that God wiped out all humanity because of this story, then wouldn’t it be really silly if this story wasn’t actually historically true? Well yes, it would be, but those are the very questions at issue! Isn’t it possible that there might be some other theological purpose for the story to be there, one that is mythical or perhaps even lost to time because we are living thousands of years after it was first composed and written down? No, for Hoffmeier, we must simply assume that it is historical because if it is not, then… what? It’s not even clear, because his point is entirely rhetorical rather than based in reality.

Fascinatingly, Hoffmeier’s extensive analysis of the Flood narrative seems to undercut his rhetorical point above. After noting the presence of Flood narratives elsewhere, he takes the similarities in the Genesis Flood account to the Babylonian one to somehow mean it is historical, despite his own admission that it seems to have been “consciously aimed at refuting the Babylonian worldview” (54). One would think that after this admission, Hoffmeier and other defenders of the Flood as history might see an incongruity in their clinging to it as a story that really happened as written and their conceding that the story is deliberately intended as a refutation of a differing worldview. But no, that’s not what happens. Instead, Hoffmeier simply argues that it is part of the shared memory of Israel and Babylon, contradicting his own earlier conclusion that it was intended to refute the Babylonian worldview.

I mentioned above that the term history is “squishy” and by not defining it, Hoffmeier essentially gives himself room for hand waving about what issues might come up with claiming Genesis as such. I appreciated Kenton L. Sparks’s response to Hoffmeier in this volume when he essentially pinned him to the wall on this exact difficulty. After Hoffmeier vaguely suggests the Garden of Eden is a historical story, Sparks challenges him to explain what exactly is meant by that- “If the author of Genesis used mythical imagery, as Hoffmeier has suggested, then which images are mythic symbol and which are closer to historical representation? Does Hoffmeier believe that the cosmos was created in six literal days? Does he believe that the first woman was made from Adam’s rib? Does he believe that a serpent spoke in the garden? Does he believe that our broken human condition can be traced back to eating pieces of fruit? Does he believe in giants who roamed the pre-flood earth?” (64). Sparks doesn’t, in fact, stop there and asks even more questions, ultimately finishing: “One wonders why Hoffmeier does not answer these questions when the historicity of Gen 1-11 is the main theme of our discussion” (ibid). Yes, one wonders that indeed. When someone claims Genesis is history and doesn’t clarify what is meant by that, these are the exact kinds of questions that should be asked. And, to be clear, any attempt to answer them affirmatively while claiming that that can be backed up by modern analysis of the genre of these early chapters or by modern methods of historical analysis is an exercise in futility.

I think I have written enough here to show that a defense of Genesis as history is filled with extreme difficulties. There are many, many more I could go into, but I’d like to wrap this up for now. If a defender wishes to defend Genesis as history they must not only define history and show that it meats that definition, but they must also show that each individual detail can meet their standard of history or at least not contradict it. Hoffmeier has failed to do any of those things. Genesis is not a historical account. This conclusion should not bother those who wish to still find theological and spiritual meaning in the text. Indeed, it should be somewhat freeing, because instead of having to defend individual details of the text in such a roundabout way, they can set aside the questions of “did this really happen” and ask the far more interesting questions like “What is this text supposed to be telling us?” Hoffmeier almost made it to that point with his look at the Flood when he admitted it appears to have been written to refute the Babylonian worldview. Religious readers of the text can see that as a magnificent detail and one that might shine light on a text that is otherwise quite alarming.

Note and Citation

[1] One example is the abysmal “modified Lutheran” view of Law and Gospel in the 5 views on the same–yes, I have a bone to pick here as a Lutheran. Douglas Moo wrote that chapter. He’s not a Lutheran and it’s clear he doesn’t even have a mild grasp on the Lutheran position on Law and Gospel. He erroneously outlines the Lutheran position as a temporal split between Law and Gospel, paralleling it with the Old and New Testaments. This is completely mistaken from a Lutheran view. Then he chastises Lutherans for taking this position and says it has to be modified into whatever he makes up on the fly and calls it a modification of a view he didn’t even present to begin with. It’s truly an abysmal job and I wonder why the editor didn’t call upon some Lutherans to weigh in (because I sincerely doubt they did so) or, if one wants to write a Lutheran chapter, why they didn’t choose a Lutheran to do so.

Genesis: History, Fiction, or Neither? Three views on the Bible’s Earliest Chapters edited by Charles Halton, Grand Rapids: MI, Zondervan 2015.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Gregg Davidson vs. Andrew Snelling on the Age of the Earth– I attended a debate between an old earth and young earth creationist (the latter from Answers in Genesis like Ken Ham). Check out my overview of the debate as well as my analysis.

Ken Ham vs. Bill Nye- An analysis of a lose-lose debate– In-depth coverage and analysis of the famous debate between young earth creationist Ken Ham and Bill Nye the science guy.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “The Uncontrolling Love of God” by Thomas Jay Oord

The Uncontrolling Love of God: An Open and Relational Account of Providence by Thomas Jay Oord is the kind of book that I would have either intentionally sought out to pick apart or steered clear of a few years ago. Why? Oord unabashedly challenges traditional conceptions of divine providence, especially digging at the wounds of evil to argue that such accounts are insufficient answers to the problem of evil that we face in the real world.

Before turning to evil, though, Oord argues for the establishment of actually random events. That is, events that are not predetermined by anything. This randomness is real, not apparent, and is balanced by laws of nature which are to be read as regularities, not as comprehensive explanations of reality in lawlike terms (43-44). Going along with this, non-predetermined free choice is another factor in the world which must be accounted for in accounts of providence.

A central concept of the book is the notion of “genuine evil.” Oord notes that philosophers tend to distinguish between necessary and gratuitous evils. He essentially labels gratuitous genuine evils. These evils are “events that, all things considered, make the world worse than it might have been” (65). That doesn’t mean there can’t be goods that might come from them; rather, they are events where the actors involved could have chosen something better instead (65-66). Most Christian theological positions are keen to prevent God from being the primary cause of evil or the one predetermining evil, and there are various attempts to avoid doing this. Oord presses the point though, arguing that even having God as a secondary cause for evil, or attempting to portray overriding goods or ultimate goods as somehow overcoming evil is insufficient to adequately respond to genuine evils (chapter 4 on Models of God’s Providence delves into this deeply).

Ultimately, Oord offers an alternate model of providence, which he calls the “essential kenosis model.” As the name implies, this focuses on the notion of kenosis–divine emptying of the divine self or power–for the sake of other. The model holds that God is essentially, not accidentally good. That is, God does not choose good, but rather is good. Along with this, Oord’s position, in contrast with almost every other position of providence, argues that “God cannot unilaterally prevent genuine evil” (167). Such a position, Oord argues, is aligned with views that God cannot do logically impossible actions. On this position, God preventing all genuine evil unilaterally is a logical and actual impossibility. Thus, Oord’s position avoids the difficulty of needing an overriding good for ultimate resolution of good and evil. The palatability of this will vary, but Oord makes a compelling case for his position.

The Uncontrolling Love of God presents a challenge to more traditional conceptions of divine providence. Oord takes the position to the logical extremes, which will likely alienate some readers. For those seeking an alternative to all-controlling views of God and evil, the book will resonate.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Two “Historical Studies” chapters in “Women Pastors?” edited by Matthew C. Harrison and John T. Pless -a critical review

I grew up as a member of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, a church body which rejects the ordination of women to the role of pastor. The publishing branch of that denomination, Concordia Publishing House, put out a book entitled Women Pastors? The Ordination of Women in Biblical Lutheran Perspective edited by Matthew C. Harrison and John T. Pless. I have decided to critically review the book, chapter-by-chapter, to show that this teaching is mistaken.

Two “Historical Studies” Chapters

“Liberation Theology in the Leading Ladies of Feminist Theology” by Roland Ziegler

Pless and Harrison’s introduction to this section suggest the chapters included will demonstrate certain claims to be true. Ziegler’s chapter could be intended to support the following-

Claim 2: “Fueled by theological movements that set the charismatic distribution of the Spirit in opposition to an established office, the emerging equalitarianism of the feminist movement, historical criticism’s distrust of the biblical text, and in some cases a pragmatism that saw the ordination of women as a way to alleviate the clergy shortage… many Protestant denominations took steps to ordain women.” (Pless and Harrison, Section II introduction, 107)

Ziegler gives but the briefest historical survey of the origins of feminist theology and liberation theology. The point of the recent-ness is important, because Pless and Harrison claim in their historical section introduction that ordaining women is a novelty in the history of the church. As such, the authors must be at pains not to trace the lineage of ordaining women back too far, lest it not be such a novelty. Unfortunately, the author of the previous chapter already falsified that claim, noting that women were ordained in the earliest times of the church. The internal inconsistency of this collection of essays continues to pile up.

Anyway, Ziegler himself notes the origins of feminist theology reach back into 19th century (138), though he fails to cite any specific examples. Nevertheless, he asserts that feminist theology only “became visible” in the 1970s, thus supporting the “novelty” claims of Harrison and Pless. The 19th century is when we can find the origins of the LCMS itself, though. If novelty is such an argument against the truth of something, would these pastors also argue the LCMS is a “novel” development in the history of the church? Doubtful.

Ziegler moves on, dividing feminist theology into a somewhat arbitrary “radical” and “evangelical” segmentation. Then, over the course of two pages, he traces the “method” of feminist theology (notably, all from just one author). Then, he outlines various alleged beliefs from feminist theology, whether about its doctrine of God or Christology. Again, one author’s work looms large here, though a few others are cited.

The conclusion Ziegler offers is basically just that Confessional Lutheranism cannot accept feminist theology. But none of this supports the claim that the ordination of women directly arose out of the streams of feminist theology he traces. No attempt is even made to show that connection. Liberation theology, briefly referenced and defined at the beginning of the chapter, makes no impact on the rest of the chapter. It’s not clear to me at all why the chapter even attempts to cite both liberation and feminist theology, given the focus is entirely upon the latter. Readers looking for support for Harrison and Pless’s theses will find basically nothing here. It’s just a very limited look at (largely one author’s perspective on) feminist theology and then a rejection thereof.

“Forty Years of Female Pastors” in Scandinavia by Fredrik Sidenvall

Sidenvall asserts that because of women pastors, “it is impossible to proclaim any truth based on Scripture in our church” (154). With rhetorical flourish, he refers to women pastors as a form of “spiritual terrorism” (ibid). Most of this chapter is just that: rhetorical flourish. Sidenvall knows his audience will be people who agree with him, so throwing out one-liners to the crowd for applause takes up a great deal of the chapter.

The chapter turns to a short historical overview of how women’s ordination happened in Sweden. It all began, of course, with giving women the right to vote (154). This nefarious practice [my words, but not off tone for the chapter] led to liberalism taking hold. A neo-church movement then arose which led to an orthodox pushback. But then, the state appointed an exegete “who, though far from having any position in the faculties, had the qualifications to produce the answers the politicians wanted” (156). And what did the politicians want!? Women pastors! Or… something. The political pressure put on the church meant the church caved. So goes Sidenvall’s story. The facts he shares speak a slightly different tune, as he complains about the democratic organization of the churches, which thus allowed theology to flow with the times (157).

The rest of this historical survey holds up the tiny confessional remnant as a kind of heroic effort against a liberalizing church, apparently making one of the confessional leaders the “most hated person in Sweden” (162). Again, this rhetorical flourish plays well to those in agreement, but it seems little more than lionizing on the outside. Finally, Sidenvall turns to the impact of ordaining women, which includes stories of “horrifying… psychological torture” happening to those who are against women pastors going to “pastoral institutes of the Church” (165). Sidenvall ends on a hopeful (for him) note: Perhaps there will even come a day when the culture as a whole will find itself in chaos after having experimented with the roles of gender and deconstructing family, and there will be a desperate need for change” (166). This hopeful (he uses the word hope) message is alarming, showing a pastor genuinely hoping for societal chaos, breakdown, and turmoil. Rather than praying for peace, he hopes for destruction.

The chapter, of course, does basically nothing to demonstrate the claims Harrison and Pless said would be shown by the chapters in this section. And this chapter ends the section. My previous post noted how the chapter actually contradicted Harrison and Pless’s claims on a number of points. These two chapters basically do nothing to advance them. And that’s it! There’s nothing left. What we’ve been offered is an oddly terse summary of feminist theology (with the very briefest gloss of liberation theology at the front), and a rhetoric filled look at women pastors in Sweden followed by a hope for societal chaos. How does this support the claim that women pastors aren’t or should not be ordained? I’m unsure. It’s those opposed to them here who are hoping for destruction.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

Interpretations and Applications of 1 Corinthians 14:34-35– Those wondering about egalitarian interpretations of this passage can check out this post for brief looks at some of the major interpretations of the passage from an Egalitarian viewpoint.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Eternal Conscious Torment, Degrees of Suffering, and Infinite Punishment

One argument for affirming Eternal Conscious Torment (hereafter ECT) is that it allegedly makes more sense of divine justice.* So, for example, the argument is that awful dictators like Stalin or Hitler being simply executed by God (such as in some views of Conditionalism) is unjust, but rather their punishment must be much more severe in order to satisfy justice. To rework ECT and allow for a more palatable sense of justice, the concept of degrees of punishment is sometimes introduced, such that those who did not commit great atrocities suffer less than those who did. Another argument for ECT is that because God is infinite and God is the wronged party when creatures sin, those finite creatures must suffer infinite punishment for justice to be served. Below, I’ll argue that these arguments related to ECT fail.

Degrees of Punishment

Intuitively, it seems unjust that someone who say, did not come to belief in Jesus Christ due to not hearing the Gospel proclaimed have the same level of punishment in eternity as someone like Stalin does or someone who intentionally misleads people about Christ. Thus, the argument goes, to preserve that sense of justice, there are degrees of punishment in hell. Instead of debating the merits of that argument, I’d like to highlight a significant problem for the ECT position on this view. Namely, ECT does not, in fact, allow for degrees of punishment on the basis of it being eternal.

Eternity is a long time. It is infinite. Defenders of ECT are adamant: this punishment goes on forever, without end. However, once one introduces the infinite into real life situations, such as eternal conscious torment, some difficulties appear. To explain, examples like Hilbert’s Hotel can help explain some of these situations. In Hilbert’s Hotel, there are infinite rooms which are all full with infinite people. But, alas, a guest would like to check in! No problem, Hilbert just moves every guest down one room, thus making room for another guest! It sounds paradoxical because it is. That’s not how things in the real world seem to work. Nothing truly seems infinite.

For defenders of ECT, hell is infinite. Let’s say we have two people in ECT’s view of hell. One, Jill, has a degree of punishment significantly smaller than that of Joseph Stalin. Let’s say that Jill’s suffering is only 1/1000 that of Stalin. Now, to determine how much suffering any individual suffers, one can multiply the amount of suffering by the amount of time they’re suffering that amount. But infinity multiplied in such a fashion remains infinity. In both Jill and Stalin’s case, that amount of time is infinite. Thus, their total suffering is equal, because the quantitative suffering they receive moment to moment ultimately multiplies to be an equal, infinite amount of suffering. The aggregate suffering which each endures is infinite. All of the unsaved, regardless of who they are or what actions they did in this life, ultimately suffer an equal amount: infinitely.

This means that the argument about degrees of punishment related to ECT fails, because all of the lost suffer the same ultimate fate: infinite suffering.

Different Infinites

It is true that there are different kinds of infinities in math. However, those differences aren’t relevant in this case for a few reasons. One reason is that no individual’s suffering is infinite at any given moment (this is important, as we will see in the next section). That is, we can quantify one’s temporal suffering, say, on a range of 1-1000. Because of that, the calculus of infinites doesn’t change here. Though there are different kinds of infinite, the degrees of punishment being discussed here are not–and cannot–be significant enough to impact that ultimate amount of aggregate suffering in a way that makes the infinites mathematically discernable.

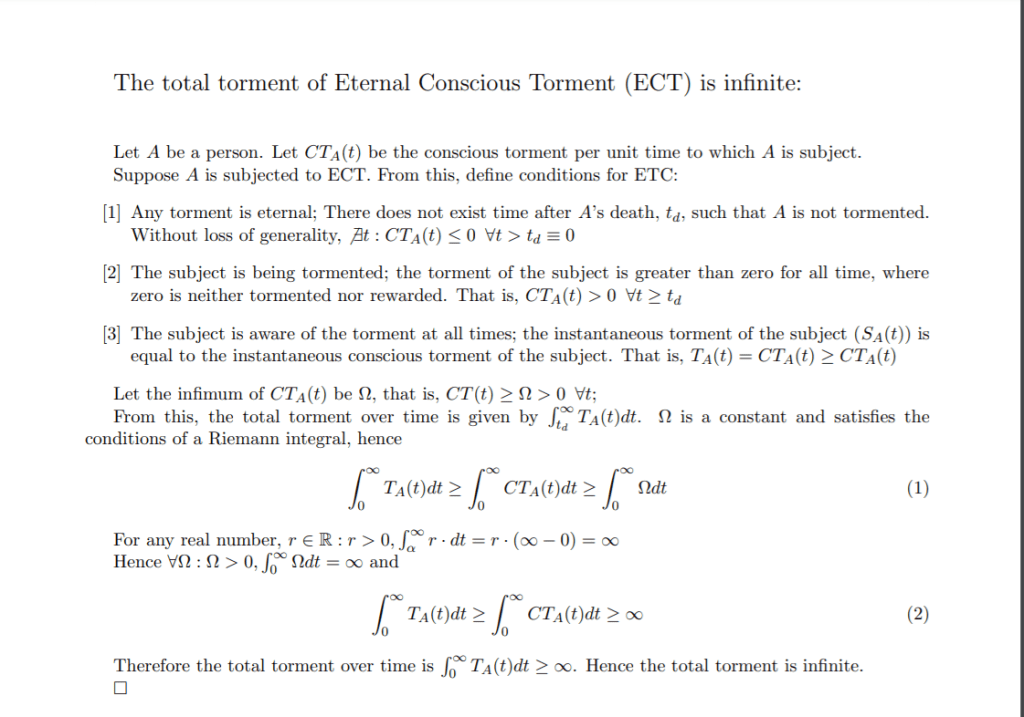

The other problem is that mathematical proof can show that the different type of infinites don’t matter in the case of ECT. See the Appendix below.

Infinite Suffering and the Justice of an Infinite God

Another argument in favor of ECT is that, because one has wronged an infinite being, the punishment must be infinite. If I’m right about the above problem for ECT, ECT succeeds at providing infinite aggregate punishment, but only at cost of undermining any possibility of degrees of punishment. But the fact that it is only aggregately infinite yields another problem: no finite being actually suffers an infinite amount, which undermines another argument for ECT.

Humans are finite–this is a given and indeed is part of the proponent of ECT’s argument for needing an infinite punishment for wronging an infinite God. However, because humans are finite, they are incapable of suffering, at any given moment, an infinite amount. So, while their suffering will be an aggregate or ultimate infinity, given the infinite time of eternity, at no point in time can one say “Stalin has suffered infinitely.” The reason for this is that, at any given moment in eternity, the amount of suffering would still be finite, having not yet reached an infinite amount. For every given moment, t, there is another moment, t +1, that would yield more suffering.

What this means, then, is that no one in hell, at any given moment, has suffered or will have suffered infinitely (excepting the abstract ultimate or aggregate eternity). But if God’s justice can only be served by meting out infinite suffering to finite creatures, then God’s justice is never satisfied, for all such creatures doomed to infinite suffering must continue to suffer without ever reaching the actual infinite amount of suffering. Therefore, the argument in favor of ECT from God’s infinite justice fails.

Addendum: Infinite Life in Christ

Another outcome of my reasoning is that degrees of reward in heaven must ultimately be the same as well. Thus, any view which deems it necessary for there to be varying degrees of eternal bliss faces the same difficulties as ECT does, for all of the saved will experience infinite bliss. Therefore, views of eternal rewards which rely upon infinite rewards fail.

*Interestingly, the opposite is also often held by those who argue for positions apart from ECT.

Appendix: Mathematical Proof and Infinite Suffering

This mathematical proof was made by Jonathan Folkerts, a Physics Doctoral Student.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.