Omniscience

Is Middle Knowledge Uncontroversial?

I was reading a recent blog post at one of the sites from which I read every post–the Pastor Matt blog–and discovered a point of some importance for those interested in the debate over omniscience and divine foreknowledge. His post “Middle Knowledge Misunderstood” is a brief introduction to the concept of middle knowledge. My focus is not going to be on that topic so much as on a claim made in the article: that middle knowledge is uncontroversial. Simply put, this claim is mistaken. Middle knowledge is the subject of much debate to this day.

I was reading a recent blog post at one of the sites from which I read every post–the Pastor Matt blog–and discovered a point of some importance for those interested in the debate over omniscience and divine foreknowledge. His post “Middle Knowledge Misunderstood” is a brief introduction to the concept of middle knowledge. My focus is not going to be on that topic so much as on a claim made in the article: that middle knowledge is uncontroversial. Simply put, this claim is mistaken. Middle knowledge is the subject of much debate to this day.

Middle knowledge is God’s knowledge of counterfactuals of creaturely freedom: specifically, God’s knowledge of “If x, then y” in regards to human and other created beings’ freedom. It is more than that, and yes I am simplifying this quite a bit.

Middle knowledge has been the subject of no little amount of my efforts in studying, and when I read the claim that it is uncontroversial, I was taken aback. Frankly, to say that middle knowledge is not controversial is just entirely mistaken. I shall now demonstrate that point.

First, middle knowledge is controversial among those who deny that God has absolute knowledge of the future, namely, open theists. William Hasker, John Sanders, Clark Pinnock, and other open theists each explicitly deny the existence of these counterfactuals that make up middle knowledge. Greg Boyd, another prominent open theist, argues in multiple places that the “would” counterfactuals of middle knowledge (i.e. in situation x, person s would do y) should instead be “might” counterfactuals because “would” counterfactuals can have no truth value (see, for example, his response to William Lane Craig in Divine Foreknowledge: Four Views (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity, 2001).

Second, middle knowledge is controversial among Calvinists. Paul Helm, a noted Calvinist philosopher, writes:

Since the Reformed held that all that occurs is unconditionally decreed by God and that men and women are responsible for their actions, they saw no need for a third kind of divine knowledge, a middle knowledge, which depended upon God foreseeing what possible people would freely do in certain circumstances.

In other words, middle knowledge is superfluous. Helm goes on to state as much:

Not only is middle knowledge unnecessary to an all-knowing, all-decreeing God, but the Molinists’ conception of free will makes it impossible for God to exercise providential control over his creation. Why? Because men and women would be free to resist His decree.

I would contend that most any theological determinist should hold to a similar belief regarding middle knowledge. On such a position, middle knowledge is unnecessary and indeed contrary to their entire system. Certainly Calvinists in general would deny that middle knowledge is necessary or uncontroversial.

Third, Thomists, I believe, would also reject middle knowledge–and historically have–for a number of reasons, including the notion that it entails potentiality in God. The reason it would do so is because of the whole structure of modality–including possible worlds–which advocates of middle knowledge tend to put forward as well. If the assertion is that there is a different way that things God could have created, then that implies that there is a potential there–something that any Thomistic view of the world would deny. I believe the same point would go for Scholastic thinkers in general, but I’m not familiar enough with the range of scholasticism to say that is for sure.

All of this is not even delving into things like whether those who hold to simple foreknowledge would endorse middle knowledge. David Hunt, for example, in the aforementioned Divine Foreknowledge: Four Views, also argues that counterfactuals of freedom required for foreknowledge are illogical. Frankly, I think any position of simple foreknowledge would have to deny middle knowledge because on simple foreknowledge the whole concept is just as superfluous and contrary as it is for theological determinists. After all, if we contend that God just knows the future, then there is little room for things like God’s knowledge of what creatures would do in varied situations: God just knows what the future is going to be. Again, I don’t know the range of thought within the simple foreknowledge position to say for sure, but I suspect the majority position would be to deny middle knowledge.

Now when I shared some of these thoughts with Pastor Matt, his response was to grant that open theists deny middle knowledge, but then later he also granted that some Calvinists do. My point is that even were these the only ones who denied middle knowledge, that would not qualify as being “uncontroversial.” But now, having demonstrated that it is theological determinists, Calvinists, some who hold to simple foreknowledge, open theists, and Thomists (and possibly others?) who would deny middle knowledge, I think that the point has carried: middle knowledge is not uncontroversial.

I say all of this as someone who thinks middle knowledge does exist. But I think that we need to confront the reality that Molinism–the position which most closely endorses middle knowledge–is itself highly controversial and hardly above criticism.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Middle Knowledge Misunderstood– Pastor Matt’s post on middle knowledge.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

A Dilemma for Open Theists

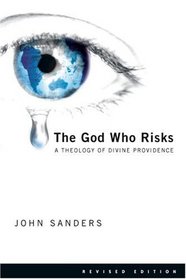

John Sanders writes in his treatise arguing for open theism, The God Who Risks, “Following Plato, Calvin declares that any change in God would imply imperfection in the divine being” (74). He proceeds to argue merely that God does change His mind. The problem is that, in arguing thus, Sanders has perhaps unknowingly presented a powerful dilemma for open theism to solve.

John Sanders writes in his treatise arguing for open theism, The God Who Risks, “Following Plato, Calvin declares that any change in God would imply imperfection in the divine being” (74). He proceeds to argue merely that God does change His mind. The problem is that, in arguing thus, Sanders has perhaps unknowingly presented a powerful dilemma for open theism to solve.

If God literally changes His mind, as Sanders desires to demonstrate, then:

1) If God changes His mind, and this brings about a better state of affairs, then it reveals that God was previously operating under a flawed or imperfect plan. [By implication, there are parts of God’s plan which could use improvement, but which God either chooses not to improve or doesn’t know how to improve.]

or

2) If God’s changing His mind brings about a worse state of affairs, then God has made a mistake, which perfect beings cannot do.

Now an immediate response could be that perhaps neither state of affairs is best. In that case, then, there would be no reason for God to change His mind in the first place and is therefore acting arbitrarily.

A response to this rebuttal may be that the change of mind is not arbitrary, but rather demonstrates God’s responsive, interpersonal nature. By changing His plan, God is responding to prayers and altering the course of history. If that is true, though, we have the first horn of the dilemma: God’s changing His mind is an improvement. And then that would mean God increased in perfection.

One may object with a tu quoque response: “Doesn’t anyone who hold that God becomes incarnate imply that God changes, and therefore wouldn’t they equally be skewered by this dilemma?”

A response to this could be simply that, assuming God has comprehensive foreknowledge, God has planned the incarnation from before the dawn of time, and so there is no changing of the divine plan.

It is interesting to see that Open Theists don’t necessarily hold that the crucifixion was God’s way of bringing about salvation in history. Sanders writes, “Though the incarnation and human suffering and death which would accompany it may have been in God’s plan all along, the cross as the specific means of death may not have been” (102). He concludes this because of his alignment with open theism, and the assertion that, given the free will of those involved, the crucifixion was not predestined (105). Not only that, but Sanders also holds that the suffering and death of Jesus were required by the atonement. Wholly apart from criticizing this theological point of interest, one can see that in this quotation, the open theist is entirely open to the dilemma. Suppose Jesus were to be assassinated, stabbed like Julius Caesar, instead of dying on a cross. Clearly, this wouldn’t suit to fill the prophecies in the Bible which were taken to reference the crucifixion (see Sanders’ discussion 102ff). Thus, it seems that this fulfillment of the divine purpose would have been less perfect than the crucifixion. Perhaps there are ways to improve on the atoning sacrifice of Christ. It seems ludicrous to type such a sentence, but if the crucifixion was unnecessary, it seems at least logically possible that a better way to provide for atonement may have been accomplished.

Finally, one may object that the dilemma could work for any who hold that God created the world. One could adapt the dilemma for the creation of the universe and say that God could have brought about a better world and didn’t (and hence is imperfect). Now there are several ways in which this argument is disanalogous to the dilemma presented above, but one could simply answer it by saying that there are specific reasons for bringing about our world over others’ which are “better” or argue that there seems to be no such thing as a way to measure worlds against each other (for some discussion of this see here).

It seems to me that only versions of theism which imply that God does not know [comprehensively] the future will be susceptible to this dilemma. While some versions of theism hold both that God knows the future and that God changes, these versions will [almost all] fail to be susceptible to the dilemma because they’ll have an account for God’s plan which is unchanging.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Is God just lucky?: Possible Worlds and God’s Providence, a Defense of Molinism

Knowing all the possible circumstances, persons, and permutations of these, God decreed to create just those circumstances and just those people who would freely do what God willed to happen. (William Lane Craig, 86).

I’ve argued previously that molinism allows for human freedom and God’s perfect knowledge of the future. One objection which has been raised to my argument is that, granting all of it, it would seem that God is just really lucky that the world He wants to actualize is possible. Looking back, we can see that the argument flows from the logical priority of God’s knowledge. Central to my defense was the notion that the possible worlds are full of the free choices of creatures. The objection therefore argues that God must simply “get lucky.” There must be a possible world which God actually wants to actualize.

The argument would look something like this:

1) God can only create that which is possible

2) The set of possible worlds covers all possibilities.

3) Therefore, if there is a world which God wants to create, He would have had to be simply lucky–there would have had to be a possible world that contained the outcomes God desired.

The objection is quite thoughtful. It is not easy to resolve. Before rebutting this objection, it is important to note that the set of all possible worlds is the same whether one is a determinist, open theist, or molinist. Granted, open theists deny that this set would include future contingents, but for now that is irrelevant. All the positions agree the set of possible worlds includes no contradictions. Thus, any position must account for the “God got lucky” objection.

I believe that molinism offers a way around this difficulty, and it does so by again focusing upon logical priority. William Lane Craig’s quote above illustrates this. God’s will is at the forefront. I suggest that God’s will is logically prior to the set of possible worlds. Consider the following argument, which focuses upon the redemption (as one of the outcomes God would desire):

1) God only wills what is possible

2) God wills the redemption

3) Therefore, the redemption is possible (modus ponens, 1-2)

4) Whatever is possible exists in the set of possible worlds (tautology)

5) Therefore, the redemption exists in the set of possible worlds (3, 4)

From this argument, it wouldn’t be too difficult to draw the inference that God isn’t lucky in regards to the possibilities–God’s will would have some kind of determining power over the set of possible worlds, because anything God wills would have to exist in a possible world. In other words, God’s will is logically prior to the set of possible worlds. That which God’s will must be possible, so it is not the set of possible worlds that determines what God can will, it is rather God’s will which determines the set of possible worlds.

A potential objection I could see is that this argument just moves the debate up another level–does God will things because they are possible or are they possible because God wills them? My response would again point to logical priority, and I would say that God’s nature (will) is logically prior to the set of possible worlds.

An objection could then be raised: “Why doesn’t God will for a world without evil?” Answer: Free will defense would work here also. God could clearly will for a world to have the redemption without destroying free will for all persons, but to will a world without evil would (possibly) impinge on all persons’ free will.

Therefore, it seems that only molinism can adequately account for both human free will and God’s omniscience and providence. Whatever God wills will occur. God is not lucky, rather, God is sovereign.

SDG.

Sources

William Lane Craig, “God Directs All Things: On Behalf of a Molinist View of Providence” in Four Views on Divine Providence ed. Stanley Gundry and Dennis Jowers, 79-100 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011).

Image Credit: I took this picture at Waldo Canyon near Manitou Springs, Colorado on my honeymoon. Use of this image is subject to the terms stated at the bottom of this post.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Against Open Theism: Scrooge and God’s knowledge of the Future

I was listening to William Lane Craig’s Defenders podcast (Doctrine of God: Part 13) and he brought up an interesting analogy about omniscience. He discussed Scrooge in Dickens’ “Christmas Carol.” The last spirit to appear to Scrooge is the ghost of Christmas to come. He takes Scrooge around and shows him all sorts of disturbing imagery that will happen. Scrooge asks the ghost whether these are things that must happen, or whether he can stop them. The spirit remains silent.

I was listening to William Lane Craig’s Defenders podcast (Doctrine of God: Part 13) and he brought up an interesting analogy about omniscience. He discussed Scrooge in Dickens’ “Christmas Carol.” The last spirit to appear to Scrooge is the ghost of Christmas to come. He takes Scrooge around and shows him all sorts of disturbing imagery that will happen. Scrooge asks the ghost whether these are things that must happen, or whether he can stop them. The spirit remains silent.

Craig pointed out the spirit would have to remain silent to have any sort of effect. For suppose the spirit knows what will happen: that Scrooge will repent and so these awful things won’t happen. But then if he tells Scrooge what he knows, Scrooge will feel little remorse about not acting to prevent them. Yet if the spirit told Scrooge these things would happen, then Scrooge has no reason to modify his behavior, for he cannot prevent the events from happening.

Craig suggests, then, that we should look at omniscience and instances of God “changing his mind” in the same fashion. This has some interesting applications in the case of Open Theism, because it undermines one of the core exegetical arguments for the position: cases of God “repenting” or “changing his mind.”

God, on classical theism, knows what will happen in every circumstance. He comprehensively knows the future (contra Open Theism). If this is so, then God would have to withhold some of his knowledge in order to bring things about, despite his knowledge that it would occur. Like the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, God would know the answer to Scrooge’s question, but would not answer him, so that he could bring it about that Scrooge would repent.

Consider Jonah. Open Theists often point to the story of Nineveh as an example of God not comprehensively knowing the future. Because God sends Jonah with the message that Nineveh will be destroyed, but then, when Nineveh repents, he shows mercy, many people say that God did not know the Ninevites would have such a reaction. Yet why should this be the case? Isn’t it plausible that God did know they would repent and that God sent the message that they would be destroyed because that is the only way Nineveh would be led to repentance? This is, in fact, hinted at later in the book, when Jonah says to God, “Isn’t this what I said, LORD, when I was still at home? That is what I tried to forestall by fleeing to Tarshish. I knew that you are a gracious and compassionate God, slow to anger and abounding in love, a God who relents from sending calamity” (4:2).

But if God had told the Ninevites “I will not destroy you” because he knew that he would not, would not the impetus of Jonah’s message lose its strength. With the threat of destruction, the Ninevites repented. Without, would they have done so? Imagine Jonah’s message going through the streets “Forty more days and Nineveh will not be destroyed!” I think it obvious that this would probably not have the same effect that the initial message was.

So it seems quite plausible that God, like the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come (in our analogous case), may refrain from telling all he knows at many points throughout Scripture. For if he told people everything he knew, he would know that they would not repent, turn aside from their evil ways, or bring about the actions he desired. The instances wherein God ‘changes his mind’ or ‘repents’ are instances of this: rather than revealing his knowledge, God withholds it, in order to bring about the ends that he desires to (and knows will) happen. We, like Scrooge, would not respond to calls for repentance if we felt it didn’t make a difference in the end.

Final note: the above account implicitly assumes molinism to be the case. So much the better for it, I say!

SDG.

This is part of a series I’ve written against the doctrine of Open Theism. If you’d like to read more, check out the original post for discussion and links.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Against Open Theism: The Infinite Knowledge of God

“Great is our Lord, and of great power: his understanding is infinite” (KJV).

“Great is our Lord, and abundant in power; his understanding is beyond measure.” (ESV)

” גדול אדונינו ורב־כח לתבונתו אין מספר׃” (Hebrew Old Testament)

Infinite Knowledge

Within Scripture we find that God knows all things. But here, in the Psalms, we read that God’s knowledge is “infinite.” Of course, this is a translation of the Hebrew, which says “…his understanding is without number/measure.” But this can also be correctly translated simply as the KJV does, “His understanding is infinite.” Thus, within Scripture, we have a picture of God’s knowledge as infinite or without number.

The Argument

1) If God’s knowledge is infinite/without number/unable to be counted, then God’s knowledge cannot be increased (it’s infinite).

2) God’s knowledge is without number.

3) God’s knowledge cannot be increased.

4) Open Theism asserts that God’s knowledge can be increased.

5) Therefore, Open Theism is false.

Defense of Premises

Premise 1 can be defended in a similar fashion as one would argue against actual infinites in the Kalam Cosmological Argument. Basically, we cannot add up to infinite. Nor, if something is actually infinite, can we increase or decrease its “number” in any way. We cannot add to infinity and increase it, nor can we take away one item from an infinite set and decrease it to some finite number. Therefore, if God’s knowledge is infinite, it is complete–it cannot be increased.

Premise 2 simply asserts what the Bible passage says.

Premise 3 follows from 1 and 2 deductively.

Premise 4 follows from the core of Open Theism. On Open Theism, God knows all things which have happened and are happening, but he does not necessarily know what will happen until it does happen. Therefore, God’s propositional knowledge would continually be increasing. Each day, he would learn an astounding number of truths which he did not previously know.

Premise 5 follows from 3 and 4; if 3 is true, 4 cannot be true. Yet 3 is true, so 4 cannot be true.

Therefore, Open Theism is false.

A Potential Rebuttal

Can the Open Theist get out of this argument? One way would be to challenge that the Psalm is not claiming God knows an actually infinite number of propositions, but simply that conceptually, God’s knowledge is so far beyond our own it appears to be infinite.

I would respond to this counter-argument by challenging the Open Theist to successfully read that off the Hebrew, which literally says “without number”/”infinite.” Open Theism, by definition, would have to entail God knowing only a finite number of propositions. If God did not know only a finite number of propositions, then His knowledge could not increase (it would be infinite). Thus, on Open Theism, the number of propositions God knows would increase by the second/minute/day. So the Open Theistic reading of Psalm 147:5 would have to read it like “[God’s] knowledge is unlimited; it increases forever.” But that reading is not justified by the text.

[Edit: Note the comment section for some great discussion of this post, wherein two commentators provided a “way out” for the Open Theist regarding my argument and a denial of premise 4.]

This is part of a series I’ve written against the doctrine of Open Theism. If you’d like to read more, check out the original post for discussion and links.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy

Against Open Theism: Definitions

I’ve encountered Open Theism a number of times in my readings and online. Many people I respect greatly fall under the category of “Open Theists.” Greg Boyd, for example, wrote one of the first apologetic books I ever read, yet he is an ardent Open Theist. Yet the doctrine of Open Theism is one with which I disagree vehemently. Therefore, I’m going to write several posts outlining a series of arguments against the doctrine.

I’ve encountered Open Theism a number of times in my readings and online. Many people I respect greatly fall under the category of “Open Theists.” Greg Boyd, for example, wrote one of the first apologetic books I ever read, yet he is an ardent Open Theist. Yet the doctrine of Open Theism is one with which I disagree vehemently. Therefore, I’m going to write several posts outlining a series of arguments against the doctrine.

Definitions

Open Theism: The doctrine that God, through his own freedom and sovereignty, chose to create free creatures (humans) which could make truly free decisions. Because God made these free creatures, he freely chose to limit his knowledge of the future, such that he would not pre-ordain their actions. Therefore, God knows only those things which God unilaterally brings about.

Another Definition

From http://www.opentheism.info/, a site collecting information and advocating Open Theism (endorsed by John Sanders, a well known proponent of the view) we can examine a 5-part definition:

1) “In freedom God decided to create beings capable of experiencing his love.” (emphasis theirs)

2) “God has, in sovereign freedom, decided to make some of his actions contingent upon our requests and actions. God elicits our free collaboration in his plans. Hence, God can be influenced by what we do and God truly responds to what we do.” (emphasis theirs)

3) “God has chosen to exercise general rather than meticulous providence, allowing space for us to operate and for God to be creative and resourceful in working with us. It was solely God’s decision not to control every detail that happens in our lives.”

4) “God has granted us the type of freedom (libertarian) necessary for a truly personal relationship of love to develop. ”

5) “God knows all that can be known given the sort of world he created… in our view God decided to create beings with indeterministic freedom which implies that God chose to create a universe in which the future is not entirely knowable, even for God. For many open theists the ‘future’ is not a present reality-it does not exist-and God knows reality as it is.”

(Again, please note these are quoted verbatim from sections on http://www.opentheism.info/; I do not claim credit for these 5 steps of the definition.)

Areas of Disagreement/Agreement

There are many areas of agreement I can share with the Open Theist. For example, I agree that God created free creatures, who have libertarian free will (1 and 4). I agree that God has not predetermined all future events (3). I agree at least in some sense that God’s actions are contingent upon our own (2)–but that’s where the differences begin.

I disagree with Open Theists on an unqualified 2 and 5. It is my belief that:

A) Future Events are knowable

B) God knows the outcome of all future events before they happen.

C) God’s knowledge of the future allows him to take into account our free choices and respond to them from eternity.

One final area of disagreement would be with the implicit idea within Open Theism of divine temporality. I believe:

D) God is essentially timeless.

What’s at Stake

“Okay, all this is well and good,” you may say, “but what’s the payoff? What’s really at stake in this debate?”

Fair questions! There are some who argue that Open Theism is a heresy, period. A simple Google search turns up dozens of articles and comments calling the doctrine a heresy. Several have attempted to ban Open Theists from evangelical circles (the ETS voted to keep two prominent Open Theists within their ranks; others have lobbied to call it heretical).

I do not think that Open Theists are heretics. While I disagree with their views, I think that they have some very good arguments for their position. I do think, however, that the Scriptural evidence excludes Open Theism from possibility. While there are many passages which could be utilized to argue for the position of Open Theism, I believe those passages which exclude the position take priority, and therefore the passages appearing to advocate the position are to be interpreted as use of metaphors or anthropomorphism.

Other Posts in the Series

This post will also serve as a host for links to other posts in the series. View them below, with brief descriptions of their content:

God’s Infinite Knowledge– Argues that Scripture clearly states God’s knowledge is infinte/without number/unlimited. Yet, on Open Theism, God’s knowledge increases, and would therefore have to be finite. Concludes Open Theism is false.

Scrooge and God’s knowledge of the future– Addresses one of the main arguments for Open Theism–that God changes his mind or repents of certain actions.

Book Review: “No Other God: A Response to Open Theism” by John Frame– I review John Frame’s work on open theism. Interestingly, Frame combats open theism with the opposite extreme: theological determinism, a view which I disagree with as adamantly (or more) than I do open theism.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy

Omniscience, Substance Dualism, and Private Access

I recently attended a seminar on God and Time with William Lane Craig (view my post on it here). One topic (among many) that caught my interest was Craig’s denial of one of the arguments for substance dualism, namely, the “private access” of some truths.

I recently attended a seminar on God and Time with William Lane Craig (view my post on it here). One topic (among many) that caught my interest was Craig’s denial of one of the arguments for substance dualism, namely, the “private access” of some truths.

J.P. Moreland argues for private access in his work The Recalcitrant Imago Dei: Human Persons and the Failure of Naturalism. He argues that mental states have an “ofness or aboutness–directed towards an object” which is “inner, private, and immediate to the subject having them” (20, emphasis his). Basically, the claim is that even were someone else to know everything about J.W. Wartick, they could not say that they know what it is to say “I am J.W. Wartick”, because they are not J.W. Wartick. Certain truths and facts are such that only the knower can know them. I cannot say I am Abraham Lincoln, because I am not him. Nor could I say that I was Abe Lincoln even were I to comprehensively know everything about Abe Lincoln from the events that occurred in his life to the exact synapses in his brain. There is something about a phrase like “I am Abe Lincoln” which only Abe Lincoln can know.

Interestingly, Craig denied that there was such a thing as “private access.” He argued that, were this the case, it would mean God is not omniscient.

Why should it follow that God is not omniscient? Well, Craig defines omniscience as “Knowledge of any and all true statements” (definition from my lecture notes). Due to the fact that God would not know true facts which have private access, argued Craig, there is no such thing as private access. This seemed like an odd way to go about denying private access in regards to substance dualism. The argument seemed to be:

1) Omniscience =def.: God knows any and all true statements.

2) God is omniscient.

3) Truths available only through private access would entail truths God does not know

4) Either God is not omniscient or there are not truths available only through private access (1, 2, 3)

5) God is omniscient (2)

6) Therefore, there are no truths available only through private access (4, 5)

The argument would work, if one agrees with the definition of omniscience in (1). But I find it more likely that omniscience is analogous to omnipotence, which is defined as God’s ability to do anything logically possible. Why should it not be the case that God can only know things which are logically possible to know? On such a view, then, private access would not challenge omniscience whatsoever, because it would be logically impossible for God to know truths only knowable to their subjects.

I brought this up to Craig, and he responded by saying that my definition of omniscience made it into a modal property, and omniscience is not a modal property. I don’t see why omniscience could not be a modal property. In fact, it seems to me as though it is necessarily modal. Omniscience entails that any being which is omniscient would have to know all possible truths about all possible worlds (for any being who did not know truths for all possible worlds could be outdone by a being which knew about more possible worlds), which is clearly a modal claim. So it seems to me omniscience is clearly a modal property, and there is no problem revising Craig’s definition to:

(7) Omniscience=def.: A being is omniscient if it knows everything it is logically possible to know.

Further, a denial of (7) would seem obviously contradictory because one who denies (7) would have to assert:

(7`): Omniscience=def.: A being is omniscient if it knows everything, including things it is logically impossible to know.

And this would lead to contradictions about omniscience. So I don’t see any reason not to revise Craig’s definition of omniscience to note that God can only know that which it is logically possible to know (for a denial of this would imply God’s knowledge could be contradictory). But then private access provides no challenge to omniscience, and Craig’s denial falls apart.

Finally, “private access” seems like an intuitively obvious feature of knowledge. How could one deny that there are truths such as “I am J.W. Wartick”? It seems clear that only I can experience what it is to be J.W. Wartick. So I think it is necessary to modify Craig’s definition and simply deny his argument, both because God cannot know or do the logically impossible, and because “private access” is such a well-established phenomenon.

Edit: See the interesting discussion in the comments below. I am forced to modify the definition I presented in this post in the comments below due to an insightful comment by Midas. Those interested can read below or just read my modification here: “A being is omniscient iff it knows all truths which are not delineated by private access [of others] or experiential knowledge [of others].”

SDG.

———

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation and provide a link to the original URL. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Molinism and Timelessness–A Match Made in Heaven (No, really!)

It seems to me that there are few matches better made than the doctrine of Divine Timelessness and Molinism (aka Middle Knowledge). I think they truly are a match made in heaven, for God Himself possesses both of these attributes/properties.

First, some definitions. God is timeless, which means that “God exists, but exists at no time” (Leftow, xi). Middle knowledge is God’s knowledge of counterfactuals (simplifying the case to some extent here, see Thomas Flint’s discussion in Divine Providence: The Molinist Account). Jointly these propositions serve as explanations for a number of phenomena of Christianity.

First, human freedom and divine omniscience is a problem curtailed jointly by these doctrines. Timelessness solves any kind of potential incompatibility by simply denying that omniscience is foreknowledge. Instead, it is simply knowledge, known all at once in one “instant” in eternity (Leftow, 246ff). That which is not in time cannot determine things “ahead of time”.

Molinism, on the other hand, can also deny any incompatibility by asserting that the counterfactuals of God’s knowledge are not under the control of God. In other words, God has no control over whether or not Jenny will freely choose to go mountain climbing. God can control the circumstances in which Jenny is placed, and then bring it about that some other counterfactual would be true (i.e. Jenny does not go mountain climbing because she stays home to nurse her ailing goldfish). But this control over circumstances does not entail control over choices. The choices remain free (Flint, 11ff).

Now, one objection to Molinism is that because God decides which circumstances in which to place Jenny before the creation of the world, he still is determining what she will do because he picks from the circumstances. But this is not quite the case. Jenny’s actions are not determined, but some of the circumstances in which she is placed are. This doesn’t preclude her free choice, however, for God only controls the situations Jenny will encounter, while her free choices remain outside of His control.

Timelessness is sometimes denied due to a perception that a timeless God could not have meaningful interactions with His creatures. This does not seem to be the case however, once one analyzes exactly what timelessness entails. Leftow argues convincingly that timelessness can be thought of as, in some sense, a parallel “time” during which all things happen at once, though not simultaneously. The relationship of successive temporal instants can be thought of in some ways as similar to logical priority. If a timeless God has middle knowledge, furthermore, then God can indeed have “real” interactions with creatures, because He, in eternity, all-at-once performs the creative, providential act. This includes the situations in which His creatures will be placed.

Thus, by His creative act, He sets the situations in which He will interact with His creatures, and this action is a true interaction because He factors in their free choices and takes such things into account. Furthermore, the objection that God’s interactions are diminished because they happen “before” the interaction occurs is a specious claim, for if God is timeless, then none of His actions occur “at a time” other than in Eternity.

Therefore, it seems to me that jointly, a molinist account and a timeless God make quite a lot of sense. This is not to say that there are no other accounts of God that make sense, but this is part of the interest of philosophy of religion, after all, particularly among Christians: the dialogue, the interaction with the Biblical texts which perhaps speak to each issue, and the different conclusions which can be drawn. These differing conclusions do not take away from or destroy the validity of our faith, rather, they ensure that we delve ever deeper, striving for an understanding of the divine Godhead.

Sources:

Leftow, Brian. Time and Eternity. Cornell University Press. 2009 (reprint).

Thomas Flint, Divine Providence: A Molinist Account. Cornell University Press. 2006.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author.

Omniscience, Necessity, and Human Freedom

I’m continually frustrated when the concept of freedom of the will comes up among people, even in Christian circles, because it seems that inevitably people start to deny that freedom of the will is incompatible with the God of Classical Theism. I am a firm believer in human freedom of the will and I believe it is fully compatible with omniscience. (Though I do not deny that our human will is corrupted by the fall into sin and that salvation is the act of God, not a work of man… These things are most certainly true.)

Generally the objection is something like this: If God knows everything and is all-powerful, then everything is pre-determined.

I still have not seen any solid argument for why this should be the case whatsoever. The key, as I understand it, is the connection between foreknowledge and causation.

I don’t see any reason to believe that if a being that is omnipotent and omniscient knows that x will happen, that being somehow causes or determines that x must happen. Why should this be the case? Simply knowing with certainty what will happen in the future does not somehow mean that this being has somehow made a causal link between its knowledge and the future, rather, it just means that this being knows what any other being is going to do.

What connection is there between knowledge of an event in the future and determining it? I’d like any kind of analytic argument to try to deny that human freedom and omniscience are compatible.

I’ve argued elsewhere that these concepts are compatible, and I’d like to make this point more clear now.

Take “P” to mean “God [in Classical Theism–i.e. omniscient, omnipotent, etc.] knows in advance that some event, x, will happen”

Take “Q” to mean “some event, x, will happen”

1. □(P⊃Q)

2. P

3. Therefore, Q

I wanted to draw it in symbolic logic to make my point as clear as possible. It is necessarily true that if God knows x will happen, then x will happen. But then if one takes these terms, God knowing x will happen only means that x will happen, not that x will happen necessarily. Certainly, God’s foreknowledge of an event means that that event will happen, but it does not mean that the event could not have happened otherwise. If an event happens necessarily, that means the event could not have happened otherwise, but God’s foreknowledge of an event doesn’t somehow transfer necessity to the event, it only means that the event will happen. It could have been otherwise, in which case, God’s knowledge would have been different. The problem many people make is that they try to make the syllogism:

1. □(P⊃Q)

2. P

3. Therefore, □Q

This is actually an invalid argument. The only thing that follows from □(P⊃Q) is that, “necessarily, if P then Q,” not “if P, then, necessarily Q.”

It is true that “necessarily, if God knows that some event, x, will happen, then some event, x, will happen”… but then it doesn’t follow from this that some event, x, happens necessarily. Thus, the event x is not predetermined simply by God’s foreknowledge of an event.

The objection is sometimes simply put forward as: Necessarily, God cannot error in his knowledge. If God knows some event x, will happen, then x will happen. Therefore, necessarily, x will happen.

Take P and Q as above

Take R to be “God cannot error in his knowledge”

1. □R

2. P⊃Q

3. Q

Again, this simply is an unsound and invalid argument. Simply stating that □R doesn’t show that for every event x that God knows, □x. It simply means that □R. R does not have a causal link to x (or Q above). It is true that □R on Classical Theism, but this does not mean that □Q or □P. There must be some argument to make P or Q necessary in order for there to be some kind of predetermined future, and I have no idea how an argument like that might go.There are ways that I can think of to formulate it, but it involves simply assuming that □R means that □P or □Q, so it would then be question-begging.

Perhaps I could take an example. Let’s say that I’m going to go to classes tomorrow (and I do hope I will, I don’t like missing classes!). God knows in advance that I’m going to go to classes tomorrow. His knowledge of this event means that it will happen, but it doesn’t mean that I couldn’t choose to stay in and sleep for a while, or play my new copy of Final Fantasy XIII, or do something more useless with my time. If I chose to, say, play Final Fantasy XIII (a strong temptation!), then God simply would have known that I would play FFXIII. His knowledge does not determine the outcome, His knowledge is simply of the outcome.

I’m open to hearing any analytic argument that manages to show how necessity can be transferred to events simply by God’s knowledge of them, but I’m skeptical as to the prospects of whether it can be done.

This argument can be seen in William Lane Craig’s writings like The Only Wise God and also in his podcast episodes on the doctrine of God.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author.