books

Question of the Week: Favorite Non-Bible Book on Jesus

Each Week on Saturday, I’ll be asking a “Question of the Week.” I’d love your input and discussion! Ask a good question in the comments and it may show up as the next week’s question! I may answer the questions in the comments myself.

Each Week on Saturday, I’ll be asking a “Question of the Week.” I’d love your input and discussion! Ask a good question in the comments and it may show up as the next week’s question! I may answer the questions in the comments myself.

Jesus the Christ

I try to make sure I’m reading one book on Jesus in my rotation of books all the time. That said, I’m starting to run low on books on Jesus. Thus, why not ask you, dear readers, for some more reading materials?

What’s your favorite non-biblical book on Jesus?

Is it an apologetics book? A work on Christology? What topic is your favorite? Let me know in the comments.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more.

Question of the Week– Check out other questions and give me some answers!

SDG.

On Acquiring Books- How to get scholarly books to read

A recent comment on my blog about how to get one’s hands on a pricey philosophy of religion book without having to fork over the near-100$ price tag got me thinking. I figured I would write this post to give some pointers for how to acquire books (not necessarily own, but get them in-hand) to further one’s study. I will be sharing specific insights for Christian scholarship, but overall this should be useful for anyone looking to read scholarly (or any!) books.

A recent comment on my blog about how to get one’s hands on a pricey philosophy of religion book without having to fork over the near-100$ price tag got me thinking. I figured I would write this post to give some pointers for how to acquire books (not necessarily own, but get them in-hand) to further one’s study. I will be sharing specific insights for Christian scholarship, but overall this should be useful for anyone looking to read scholarly (or any!) books.

I will explore a number of ways, some of which may be familiar to you, to get these books in order to consume more awesome reading. Be aware: some of these which may seem obvious at first (library) will, I hope, have more insight beyond the obvious.

Please leave comments if you think of something that I’m missing here. As I live in the U.S., this list will have some things which may only be relevant for that. International readers, feel free to share some of your own insights in the comments.

Library

We’ll start with the obvious: use your local library. You’d be surprised what they might have access to. Inter-Library Loan is a great way to get books not immediately available. Often, your local library will have partnerships with university libraries across the nation and they’ll be able to get you that book to read. If you aren’t taking advantage of this, do so. Best of all this will be free! Well, apart from the taxes you pay. So you may as well use the library because you pay for it anyway!

Another thing to look out for is any local seminary libraries. Often, they’ll let you come in and at least sit down and read, and you may even be allowed a guest pass to check books out. It’s worth exploring and the seminary will have a robust collection of philosophy of religion and theology books. I very much recommend this route if at all possible.

E-Books

Look, I know your thoughts because they were mine: “I like the smell of books”; “I like to hold the book in my hand and page through it”; “I don’t want some newfangled device!”

I hear you.

But now, be silent, because I’m going to explain why you should go for e-books and probably spring some cash for an e-reader (or at least get a Kindle app on your smart phone or something!).

1) Shelf space- a constant struggle for we book-a-holics is shelf space. E-books provide a library at your fingertips without needing anything more than a single device.

2) Old books are freely available- Literally hundreds of thousands of books are now public domain, and many are available online for free through places like Open Library. You can access things like historical apologetics books by the “armful” and they’re all free. Beat that.

3) New books are often free- Many publishers cycle through books being free for a day on Amazon. It’s worth your time to check there frequently to see if a book you may want is free. Go off of your wish list and check on Kindle to see if a book might be free, and be aware that these do change fairly frequently. It may be worth signing up for some Facebook groups or e-mail lists about free books so that you don’t miss as many (and find some you didn’t even know about).

4) Major savings on books- Have you been eyeing that 200$ treatise on a topic of interest? Oh look, it’s 50$ on Kindle. Why not save the shelf space and 150$ and just get the Kindle version? This example is extreme, but you can usually save at least a few bucks by getting the e-book version.

5) Reading e-books isn’t as bad as it sounds- Again, I hear you, I resisted for a while. Now that I have my Kindle, though, we’re inseparable. I do miss the smell of books, but the screen looks like the page of a book, and I can highlight and even take notes and bookmark pages. Moreover, it’s lightweight and small so it is easy to carry. Also, imagine that vacation: instead of trying to lug a backpack full of 25 books, you could bring your e-reader and have access to an entire library (I have well over 200 books on mine).

Buy Books

Another obvious instruction, but there is an art to this. That is, pretty much everyone has a limited budget for buying books (if any–I know how that goes!), along with limited shelf space. So it’s not as simple as just saying: “Yeah, go spend that 150$ on that latest book from Brill” (very pricey publisher). Here are some things I’ve done to both discipline myself and acquire books in a more meaningful fashion.

1) Set a clear budget- obviously, without this you either have no way to buy books, or you will buy too many and not eat. Whether it’s 1$ a week and you save up for 50 weeks before you buy that one book or it’s 50$ a week and you’re drowning in books, set a budget.

2) Be aware of space requirements- once more this seems obvious, but try to keep in mind the space books take. If you have limited shelf space (and we probably all do), keep in mind that a 500 pager is going to take up a lot more space than a 150 page book. For that 500 page monstrosity, it might be better to look at E-Books above.

3) Make AND MAINTAIN a wish list- We all have wish lists, but have you thought of this as a way to limit or direct your buying? While browsing through Amazon and throwing things on your wish list, why not also try to think along the lines of expense and need? A good rule is this: leave a book on your wish list for at least 2 weeks before buying. If those two weeks are up and you still really want the book and have budged for it, then it’s more likely it wouldn’t just be an impulse purchase. Another thing to keep in mind is to prioritize your buying: some books we have an idle interest in reading; others are necessary for our research. The one’s in the latter category should almost always trump the former.

Look Into Review Programs

Many publishers are willing to give you free books in exchange for reviews. For example, Crossway has a blog program in which they make available some e-books to bloggers and you can review 2 a month or up to 12 a year. That’s 12 books you both don’t have to buy and also which don’t take up shelf space. Other publishers are often willing to send you books if you contact them. If there’s a new book out that you want to read, try contacting the publisher and offering to review it on your blog if they send you a copy. It’s a mutually beneficial system.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Question of the Week: Paradigm Shifting Books

Each Week on Saturday, I’ll be asking a “Question of the Week.” I’d love your input and discussion! Ask a good question in the comments and it may show up as the next week’s question! I may answer the questions in the comments myself.

Each Week on Saturday, I’ll be asking a “Question of the Week.” I’d love your input and discussion! Ask a good question in the comments and it may show up as the next week’s question! I may answer the questions in the comments myself.

Paradigm Shifting Books

I’ve been re-reading a lot of books recently and it’s made me reflect on how some books have truly changed how I thought about things. Sometimes, this even applies to whole paradigms and ways of thinking instead of simply changing how I viewed a specific event or whether I thought a specific fact was true or not. In light of that:

Have you ever read a book which forced you to re-think a topic so thoroughly that it shifted your paradigm? What was it? What did it make you think about?

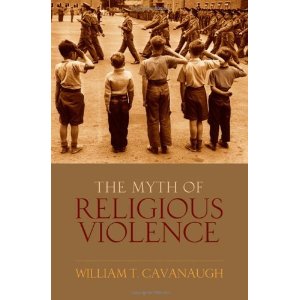

The picture on this post is one of those books for me. It made me rethink how I thought about “religious violence” and even whether there is such a thing as “religious” as a distinct category from “secular.” It was a monumentally important book for me and has continually found me going back to it and referencing ideas. I hope you, dear readers, have had books like this in your own lives.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more.

Question of the Week– Check out other questions and give me some answers!

SDG.

Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi- a Christian reflection on the most recently completed Star Wars series

Star Wars is not normally where I go to begin discussions about worldview. The most recently completed mini-series, however, “The Fate of the Jedi,” was full of material for discussing worldview perspectives. Here, I will only touch on a few of the many themes the series brought up. Some of these include world religions, objective morality, and theism. Of course, there will be HUGE SPOILERS for the Star Wars universe prior and up to this point. PLEASE REFRAIN FROM POSTING COMMENTS FROM OTHER STAR WARS STORYLINES.

Star Wars is not normally where I go to begin discussions about worldview. The most recently completed mini-series, however, “The Fate of the Jedi,” was full of material for discussing worldview perspectives. Here, I will only touch on a few of the many themes the series brought up. Some of these include world religions, objective morality, and theism. Of course, there will be HUGE SPOILERS for the Star Wars universe prior and up to this point. PLEASE REFRAIN FROM POSTING COMMENTS FROM OTHER STAR WARS STORYLINES.

I’ll not be summarizing the plot of the Fate of the Jedi series, which you may find by following the links for the individual books here.

World Religions and the Force

A huge part of the early stages of Fate of the Jedi involved Luke Skywalker and his son, Ben, traveling around the galaxy and visiting other various Force-using schools. These different Force-using schools paralleled, in many ways, various world religions. For example, the Baran Do Sages held onto a kind of gnostic way of knowing, where secret knowledge was preserved by a select group of masters to pass on from generation to generation. Another example is found in the Mind Walkers, who try to separate body from soul in order to walk in a completely different reality. Not only does this also seem gnostic in its bent, but it also reflects the notion of the extinction of the self found in some Eastern religions like Buddhism and Hinduism. There are a few other schools that the Skywalkers visit throughout their travels, and each has aspects of at least one world religion reflected therein.

Of interest is that the way the series approached the various parallels to world religions is that many of them appeared to be fairly obviously wrong. That is, they had a feel of wrongness to them, but they also seemed to get aspects of reality wrong. The Mind Walkers, for example, allowed their bodies to waste away while they experienced their own way of entering into the Force. One cannot help but sense a kind of aversion to this belief system, in which the body is so totally denigrated. Some of their comments also reflected a lack of concern for distinctions between good and evil. Yet again, this is a distinctive of some Eastern religions, and it is a way in which they are factually mistaken. Those who fail to make distinctions between good and evil, between reality and the mental life; they are operating under a mistaken view of reality.

The Fate of the Jedi, then, does not teach a kind of religious pluralism. Instead, it eschews pluralism for showing that some belief systems do not work. They simply do not line up with reality.

Redemption and Betrayal

The character of Vestara Khai is an extremely interesting figure. She may be the most complex character since Mara Jade. A Sith, she is captured by the Skywalkers, who initially do not trust her whatsoever (and for good reason). Yet, in a kind of typical story of conversion in the Star Wars universe, they begin to turn her to the Light Side of the Force. She realizes that her own life has not been based upon good, and she also acknowledges a distinction between good and evil. Her realization is centered around her relationship with her family and friends (such as they are). For a little while, it seems that Vestara is a true convert.

Yet the reader knows throughout that although Vestara has changed her whole way of viewing the universe, she is not entirely a convert. She still puts herself first. In fairness to her, she does so thinking that she is putting others first, and she often does seem to prioritize the needs of Ben–whom she’s come to love–over herself. But when push comes to shove, she betrays the trust of the Skywalkers in the most dire possible way, by giving away the secret identity of a loved one and dooming her to a life of dodging the Lost Tribe of the Sith. A commentary on the darker side of human nature, Khai’s life in the books also begs the question of where one goes from there: what redemption may be in store for someone who seems to have ruined all chances at salvation?

Prophecy and the Celestials

The notion of prophecy is found throughout the Star Wars universe. There was the prophecy of the “Chosen One”; later, prophecies revolved around the Sword of the Jedi and the Unification of the Force. Each of these prophecies were expected to be fulfilled. In the Star Wars universe, prophecy is the product of the Force. One wonders, however, how this plays out with what is an essentially impersonal force. It seems that in order to give revelation, there must be some kind of personal reality; for prophecy relates to the actions of persons.

Ultimately, readers encounter the Celestials–a group of beings (Father, Son, and Daughter… and later Mother) of extreme power. These beings are tied into the whole plot of the expanded universe books of Star Wars in some ingenious (and sometimes a bit questionable) ways. Although these beings may appear to parallel a kind of pantheon, it becomes clear that they are not. They may be seemingly eternal, but they are also contingent: it was entirely possible for them to be destroyed. Again, it is not these beings who drive reality; it is the Force. The Force is the power in the universe, the ‘all in all’ of the Star Wars universe. Yet, as I’ve argued above, it is hard to envision the force as entirely impersonal. It delivers prophecies and sometimes even answers the call of those in need. The “Trinity” created and driven by the Force ultimately drive the Force themselves in many ways.

Conclusion

The Fate of the Jedi series explores a huge number of issues related to worldview. I didn’t get to nearly all the major issues, let alone the minor ones, which come out throughout the series. Of interest is how the series clearly brought up world religions in such a way as to avoid pluralism, but rather provided ways to distinguish between truth and falsehood in religion. Prophecy begs for a personal being, yet the allegedly impersonal Force provides it. It was great to experience the Star Wars universe in such a way as to have it bring up so many issues of worldview in often thoughtful and, frankly, thought-provoking ways.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

“Fitzpatrick’s War”- Religion, truth, and forgiveness in Theodore Judson’s epic steampunk tale– I take a look at the book Fitzpatrick’s War, a novel of alternative history with steampunk. What could be better? Check out some of the worldview issues brought up in the book.

I have discussed the use of science fiction in showing how religious persons act. Check out Religious Dialogue: A case study in science fiction with Bova and Weber.

Source

Troy Denning, Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi- Apocalypse (New York: Del Rey, 2012).

Disclaimer: The images in this post are copyright of the Star Wars universe and I use them under fair use. I make no claims to ownership of the images.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Really Recommended Posts 2/22/13

I have to say, the posts for this week are really the cream of the crop. Make sure you follow the blogs I link to here, because they are constantly amazing. We look at The Mortal Instruments, Richard Carrier and the Jesus Myth, the power of prayer, how pornography can destroy the brain, science fiction, and a fun interview!

I have to say, the posts for this week are really the cream of the crop. Make sure you follow the blogs I link to here, because they are constantly amazing. We look at The Mortal Instruments, Richard Carrier and the Jesus Myth, the power of prayer, how pornography can destroy the brain, science fiction, and a fun interview!

Empires and Mangers: The Mortal Instruments– What’s all the buzz about surrounding the upcoming movie and the books called “The Mortal Instruments?” Anthony Weber analyzes the series in this fantastic post. I haven’t read the books and I was still fascinated. Do check this one out, as it will be all over culturally. Also, follow this blog because the posts are consistently at this quality. It’s a must-read every time.

Does Richard Carrier Exist?– A fun but rigorous look at whether Richard Carrier exists. Why? Richard Carrier is best known for his denial that a historical Jesus ever existed. Here, Glenn Andrew Peoples and Tim McGrew partnered to use Carrier’s methods on him, to devastating results.

C.S. Lewis on the efficacy of prayer– Have you ever heard the objection that prayer doesn’t work? Matt Rodgers takes on this argument through C.S. Lewis, the eminent Christian writer and theologian.

The Effects of Porn on the Mail Brain– This is a scary, uncomfortable post. The topic is pretty self-explanatory. Pornography is devastating. Let us pray for those under its chains and continue to work against it.

Grand Blog Tarkin– Have fun with this one. It is a blog dedicated to looking at the social and military themes in science fiction and fantasy. I cannot describe how nerd-awesome this is (just a hint: if you get the title, you’d love it… even if you don’t, you’ll still love it). You must check it out.

Mike Robinson interviews J.W. Wartick– A bit of a plug here: check out Mike Robinson interviewing me on his (great!) blog. I’d love your comments.

Religious Dialogue: A case study in science fiction with Bova and Weber

I love science fiction. One of the main reasons is because it provides a medium for authors to share their philosophical outlook for the world. Some authors portray their vision of what the world would like like if…. and what fills in that “if” is that which the author would like readers to be wary of our condemn. For example, distopian fiction often takes some aspect of society and shows how if we allow it to run rampant, we will create a world wherein we would not want to dwell. Other authors use science fiction to portray an ideal (or nearly ideal) society and show how the things they are promoting or believe fit into that ideal society.

Ben Bova and David Weber are two of my favorite science fiction authors. Bova blends hard science fiction (sci-fi which is largely focuses upon the applications of science that is at least seemingly possible) with great storytelling. His “Grand Tour” series of books is the story of humanity spreading across our solar system and even finding life on mars and founding a colony on the moon. David Weber writes military science fiction on an epic scale, complete with amazing battles in space (and who doesn’t like some big explosions in space?). I was fascinated to see both authors interact with Christianity, particularly on a fundamentalist level, and see how they took that discussion.

David Weber’s book, The Honor of the Queen portrays its main character, a woman named Honor Harrington, becoming involved in a wartime crisis between two nations which are complementarian in nature. Complementarianism is the belief that women should not be ordained in the church and it is a very real and somewhat pervasive view within the Christian church today. I have discussed it and the rival view that women should be ordained/treated as equals (egalitarianism) at length elsewhere [scroll down to see other posts].

What really struck me is that David Weber fairly presented firm believers as a spectrum. He showed that believers can be reasoned with and even persuaded to believe differently based upon evidence. Furthermore, he showed that even those who may line up on the side with which he disagrees [presumably–I don’t know where he stands on the issue] are not all (or even mostly) blinded by faith or foolishness. Rather, although there are some truly evil and disillusioned people, Weber shows that many are capable of changing their position or at least acknowledging that rival views are worth consideration.

The most vivid portrayal of this theme is found in a conversation between Admiral Courvosier and Admiral Yakanov. Courvosier is from the same nation as Honor Harrington and wholly endorses his female officer in a position of command. They discuss Captain Honor Harrington:

[Yanakov responds to Courvosier’s question about his society’s reaction to Honor]: “If Captain Harrington is as outstanding an officer as you believe–asI believe–she invalidates all our concepts of womanhood. She means we’re wrong, that our religion is wrong. She means we’ve spent nine centuries being wrong… I think we can admit our error, in time. Not easily… but I believe we can do it.”

“Yet if we do[” Yanakov continues, “]what happens to Grayson [their world]? You’ve met two of my wives. I love all three of them dearly… but your Captain Harrington, just by existing, tells me I’ve made them less than they could have been… Less capable of her independence, her ability to accept responsibility and risk… How do I know where my doubts over their capability stop being genuine love and concern?”

The exchange is characteristic of the way Grayson’s people are treated throughout the book. They are real people, capable of interacting with other views in honest ways. They feel challenged by a view contrary to their own. Some react poorly, and there are extremists who are blinded by hatred and anger. Yet all of them are treated as people with real concerns shaped by their upbringing and backgrounds.

Honor Harrington ends up saving Grayson, and at the end of the book, she is commended by the rulers of that planet. She talks to the “Protector” [read: king/president]:

“You see,” [said the Protector] “we need you.”

“Need me, Sir?” [Responded Honor]

“Yes, Grayson faces tremendous changes… You’ll be the first woman in our history to hold land… and we need you as a model–and a challenge–as we bring our women fully into our society.”

Weber thus allows for even ardent supporters of specific religious backgrounds to respond to reasoned argument and to change. They are capable of interacting on a human level and deserve every bit of respect as those who disagree with them. Again, there are those who are radicals and will not be reasoned with, but they are the minority and they do not win out.

Weber therefore presents religious dialogue in The Honor of the Queen as a genuine interaction between real people from differing backgrounds. Those who are “fundamentalist” are capable of changing their views when challenged with a rival view which out-reasons their own. Religious dialogue is possible and fruitful.

Ben Bova’s whole “Grand Tour” series has a number of dealings with “fundamentalists.” He never really defines the term to be specifically Christian but one can tell when reading the books that it is pretty clear he is referencing hardcore fundamentalist evangelical Christianity.

I recently finished reading Mars Life, one of the latest in the series. The book focuses upon the continued research following the discovery that there was once once intelligent life on earth. There are major forces that are slowing down the exploration of Mars in the book. First, Earth is dealing with a number of major problems from global warming. There is flooding that has almost submerged Florida and other areas of the Midwest (in the U.S.) and the rest of the world is suffering even worse. Thus, people are wary of giving money to research on Mars when there is so much to do more locally. The primary impediment to Mars exploration, however, are the “fundamentalists” (again, an ill-defined term which seems to include some version of Christianity, given that they reference the Bible) who are actively working to cut off funding because they perceive the discovery of life on Mars as a direct threat to fundamental beliefs like anti-evolutionism and the like.

Bova’s treatment of extremist positions in religion is somewhat disingenuous in my opinion, particularly when one compares his portrayal with that of Weber. Bova tends to illustrate religious fundamentalists as a black and white issue. Basically, if you are a hardcore believer, you’re in it for power and control, you are willing to incite violence to achieve your ends, and you are incapable of reasoning. Again, note the contrasts with Weber’s depiction above. A few examples will help to draw this out.

On page 142 and following there is a discussion about putting together a panel to discuss the finding of a fossil on Mars. The interaction shows that no matter what, fundamentalists cannot accept scientific findings:

“Look,” said the bureau chief… “everybody’s calling it a fossil…. …”Call it an alleged fossil, then,” insisted the consultant (from the fundamentalists)… [The group then continues to suggest terms for the fossil:] “A probable fossil?” …”A possible fossil”… [Then, finally] “Say that the scientists believe it’s a fossil and until proven otherwise that’s what we’re going to call it.”

Here one can see that fundamentalism is intrinsically tied to an anti-science mentality. The key for them is to use words which deny absolutes, essentially skirting issues rather than discussing the truth. But that’s not all there is to it. Later on, one of the fundamentalists is engaged in a discussion about “requesting” that some lyrics in music they view as morally reprehensible be changed. The musician flat out refuses, angering the fundamentalist in the process. The section closes as follows:

[The musician] was shot to death at a Dog Dirt concert three months later. His killer surrendered easily to the police, smilingly explaining that he was doing God’s work.

What is interesting about this example is that it is illustrative of a number of such examples throughout the book. These are completely unrelated to the main plot. Rather, it seems what Bova is doing is very explicitly showing that fundamentalists are unafraid to use immoral tactics, censoring, and even incite violence in order to get their way. Theirs is an unquestioned and unquestionable faith. Those in power in fundamentalism are inherently evil and devious. They only want to control. Again, these asides are in no way tied to the plot of the book. It’s almost as though Bova is preaching a different worldview, one which views religiosity as inherently dangerous and violent, with few exceptions.

There is one positive example, however. A Roman Catholic, Monsignor Fulvio DiNardo, who is also a world-renowned geologist decides he wants to go to Mars to find the answer to a question about faith which is pressing on him. Namely, why God would exterminate an entire intelligent species. His thread in the story seems to show two things: first, that fundamentalism is inherently incapable of responding to reason; second, that it is possible to have reasoned faith and science together. The second point is illustrated very well when DiNardo is finally on Mars. He suffers from a likely stroke and is dying and begins a dialog with God:

Why did you kill them, Lord? They were intelligent. They must have worshipped You in some form or other. Why kill them? How could you–

And then DiNardo understood. Like a calming wave of love and peace, comprehension flowed through his soul at last… God had taken the Martians to Him! Of course. It was so simple, so pure. I should have seen it earlier. I should have known. My faith should have revealed the truth to me.

The good Lord took the Martians to Him. He ended their trial of tears in this world and brought them to eternal paradise. They must have fulfilled their mission. They must have shown their Creator the love and faith that He demands from us all. So He gave them their eternal reward…

The light was getting so bright… Glaring. Brilliant… Like staring into the sun. Like looking upon the face of… (297-298)

So Bova does offer a counterbalance to fundamentalism, and I appreciate that portrayal. Although DiNardo’s death and his revelation receives very little further comment (and no further comment at all on the revelation), it seems as though it is positively portrayed.

A reason for criticism is that Bova is uncompromising with fundamentalists. I’ve already drawn out his portrayal of them, and it seems to me to be a bit disingenuous. Although there are plenty on the “religious right” who would be all too happy to be able to legislate all morality, control the media, and deny well-attested scientific findings, I have hardly found that to be the majority. And certainly, fundamentalism is not a homogeneous entity filled with people who are trying to control everyone else. I’ll grant that this is a work of fiction, but in light of how Weber was able to handle a fairly similar issue with respectful portrayals of the ‘other side,’ I had hoped for more from Bova, whose work I enjoy greatly. For Bova, it seems, religious dialogue is not a real possibility, with few exceptions. Fundamentalists are incapable of reasoning and are barely even convinced believers; rather they are using their positions of authority within their organizations to consolidate power and execute their own prerogatives on their witless followers.

Fair Discussion

It seems pretty clear to me that David Weber provided a better model for utilizing science fiction in religious dialogue than Ben Bova did. The people representing the ‘bad guys’ in Weber’s book did have some who were truly evil and/or beyond reason, but also had many with whom reason resonated. When confronted with rival views, they were thoughtful and even receptive. On the other hand, the characters with whom Bova disagreed were a true black/white dichotomy with the “good guys.” Fundamentalists were bad. Period. He portrayed them as power-hungry, censor-happy maniacs. Although there was one notable exception (the Catholic priest, DiNardo), who showed a bright spot for “believers” at large, he was by far the exception.

It seems clear this study has applications for real-world dialogue about religion. When we interact with other worldviews, we should be capable of treating the other side with the same kind of dignity we would like to be treated. Although other worldviews may have their extremists who will not respond to reason, our attitude should be that of the humble friend trying to explore the beliefs of the “other.” The “other” is not that which must be demonized, but rather understood and with which to interact.

More Reading

I explore the theological implications of life on other planets.

I discuss a book which will change the way you think about about the notion that religion is violent. It also deals with the notion of the religious “other” as a construct.- William Cavanaugh’s The Myth of Religious Violence.

Sources

Ben Bova, Mars Life (New York: Tor, 2008).

David Weber, The Honor of the Queen (New York: Baen, 1993).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Heresy: A History of Defending the Truth” by Alister McGrath

There is a trend today to see heresy as a forbidden fruit. What is heresy?; Who says these views are wrong?; Aren’t heresies just the losers in a power struggle?–these are but a few examples of the questions being asked about heresy. Alister McGrath’s book,Heresy: A History of Defending the Truth

There is a trend today to see heresy as a forbidden fruit. What is heresy?; Who says these views are wrong?; Aren’t heresies just the losers in a power struggle?–these are but a few examples of the questions being asked about heresy. Alister McGrath’s book,Heresy: A History of Defending the Truth seeks to explore many of these issues while providing a historical background for those looking into the topic.

“A heresy,” states McGrath, “is a doctrine that ultimately destroys, destabilizes, or distorts a mystery rather than preserving it… A heresy is a failed attempt at orthodoxy, whose fault lies not in its willingness to explore possibilities or press conceptual boundaries, but in its unwillingness to accept that it has in fact failed.” (31, emphasis his).

One might wonder why McGrath utilizes this view of heresy, and it is important to see that his definition stands between two misunderstandings of the historical context of the development of heresy. McGrath argues that there are two positions about the history of heresy which are extremely popular but also highly anachronistic. The first is that heresy is something from outside of the church which was able to somehow “get into” the church and corrupt it (34); the second erroneous view is that “What determines whether a set of ideas is heretical or not is whether those ideas are approved and adopted by those who happen to be in power. Orthodoxy is simply the set of ideas that won out, heresies are losers” (81). Both positions suffer from an anachronistic view of the history of heresy and tend to over-emphasize certain aspects of that development.

The notion that heresy is some kind of “Trojan horse” smuggled into Christianity from without is historically untenable (34). Furthermore, this view generally holds that “Heresy was a later deviation from [the] original pure doctrine” (65). Instead, “heretics were insiders who threatened to subvert and disrupt [the church]….” (35). However, the fact is that the notion of early Christianity holding to the best orthodoxy is a purely fictional historical concept. Rather, doctrine developed as new challenged were presented to the Christian faith or new truths were explored (66-67). Heresy was part of this development. Heresies were ideas that failed to take hold within Christianity because it was deemed to undermine the strength of the Christian faith as a whole (83).

Therefore, McGrath argues, it can be seen that the second view of the development of heresy is also historically mistaken. There was an orthodox core from which doctrine developed, and heresies were seen as defective (81ff). “The process of marginalization or neglect of these ‘lost Christianities’ generally has more to do with an emerging consensus within the church that they are inadequate than with any attempt to impose an unpopular orthodoxy on an unwilling body of believers” (81-82). Heresy was “an intellectually defective vision” of Christianity (83), rejected because it could not stand up to the theological challenges raised against it (83ff).

McGrath provides more development of the concept of heresy, and then turns from his analysis of the rise and rejection of heresy to a historical account of several early heresies. His analysis of these early heresies (ebionitism, docetism, valentinism, arianism, donatism, and pelagianism) provides significant historical support for his thesis that heresies are ultimately insufficient accounts of Christian theology and were rejected thereby. Against the thesis of Walter Bauer, who held that orthodoxy was an “ideological accident,” it is rather the case that “The relative weakness of institutional ecclesiastical structures at this time, including those at Rome, suggest that the quality of the ideas themselves played a significant role in their evaluation…” (133).

It is also important to note that heresies are not necessarily tools aimed to destroy Christianity from within. McGrath is particularly concerned with the contextualization of heresies. These were often developed within a context of a question, like “What is the nature of Christ?” (Ebionitism). “The problem [of heresy] lay not with the motivations of [heretics], but rather with the outcomes of their voyages of theological exploration” (171).

McGrath ends Heresy with an exploration of the origins and development of heresy. Heresy, he argues, develops through 5 major strands, each of which usually involves turning theology towards: cultural norms, rational norms, social identity, religious accomodation, and ethical concerns (180ff). Heresies will continue to emerge as Christianity faces new challenges. Furthermore, orthodoxy is itself a process of ongoing development (221).

McGrath concludes with a vision for orthodoxy: “If Christ is indeed the ‘Lord of the Imagination’… the real challenge is for the churches to demonstrate that orthodoxy is imaginatively compelling, emotionally engaging, aesthetically enhancing, and personally liberating. We await this development with eager anticipation” (234).

Heresy is indeed something which has caught the popular imagination. McGrath’s book offers a reasonable, sound defense of Christian orthodoxy in an era wherein heresy is often portrayed as an unfairly suppressed system which should be resurrected. By providing a significant investigation of the historical background and development of heresy, McGrath avoids the two ahistorical extreme views of heresy: that it was entirely a plague from outside the church or that it was merely one of many competing ideas that happened to lose.

Christians would do well to have knowledge of the development of Christian doctrine. As more challenges are raised to the Christian faith, orthodoxy will have to continue to respond. Without a historical grounding firmly in place, Christianity is liable to change with the winds. Heresies repeat themselves (232), and Christians need to be ready to respond to these alterations of the faith. Heresies have historically been rejected not due to an internal power struggle, but rather due to their insufficient intellectual bases.

Alister McGrath’s Heresy: A History of Defending the Truth is one of those books Christians should have within reach on their shelf in order to readily access it as challenges arise. He provides an enormously useful historical evaluation of heresy which allows readers to avoid the pitfalls of ahistorical views. Furthermore, McGrath convincingly demonstrates the reasoning behind labeling a position as heretical follows from a corruption of Christianity which makes it less theologically or intellectaully viable. By providing Christians with a vision of orthodoxy and heresy that is both aware of its past and looking towards the future, McGrath has written an invaluable source.

Heresy: A History of Defending the Truth (New York: HarperOne, 2009).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Think Christianly” by Jonathan Morrow

Jonathan Morrow’s new book, Think Christianly

Jonathan Morrow’s new book, Think Christianly seeks to provide Christians with ways to think about and interact with the culture surrounding them, while critically exploring their own perspectives.

Central to the work is the notion that “Due to the unprecedented influence and availability of constant media… the thoughts, attitudes, perceptions, convictions, values, and lifestyles of those inside the church are rapidly growing indistinguishable from… those outside the church” (19). The key is to see how to help Christians “think Christianly” about every aspect of life. The Christian life is not “Sunday only” or “in church only” but rather it is an every day, every second, every interaction life. Morrow, throughout the book, seeks to touch upon nearly every area of Christian interactions with culture, providing brief introductions along with recommendations for a way forward in each area.

Part one of Think Christianly focuses on our own culture and the need to equip the next generation to interact with the issues brought up around them. Morrow provides a survey of ways people try to avoid interacting with Christianity (54ff) and suggests a threefold way to engage with our youths so they do not fall victim to the challenges to our faith. This threefold engagement is composed of 1) mentors, “people to learn from and imitate in the faith” (57); 2) peers, “people to run the race with and to spur us on” (57); and 3) a robust Christian worldview, a challenge to youths to explore what they believe and why it matters (58). Conjoined, these help provide a valuable base for youths to explore their faith among their peers and mentors who can guide them towards resources and answer questions.

Part two provides ways to integrate the Christian worldview into every aspect of one’s life. Chapter four discusses three worldviews- naturalism, postmodernism, and Christian theism. These are the worldviews pervasive currently in western cultures, and Morrow provides several ways to interact with the competing views and analyze them. Chapter five provides ways to “cultivate a thoughtful faith” and chapter six provides some ways to be confident about engagement (along with a helpful discussion of forgiveness and breaking away from anger on pages 98-99). Part Two continues with a couple chapters about living like Jesus, which are extremely insightful–we need to be sure we think of Jesus as who He was and is: the Lord of all professions, master of all crafts. Finally, part two wraps up with what may be the most important chapter of the book: “Can We Do That in Church?” Morrow argues that we must see “The local church” as “God’s vehicle to reach the world with the good news… it is also the primary place where Christians are to be equipped for the ministry” (130). By utilizing some small portion in time in church to equip believers to engage, Christian leaders can radically change the perception of Christianity as a “Sunday only” venture. If believers do not get equipped, where will they be equipped? The truth is they’ll “google it” and find people without good credentials or intentions and learn from them instead (not saying there’s nothing good online–plenty of scholars and wonderful teachers are out there, but sifting through the muck can be difficult). This chapter, I think, is the most important in the whole book and provides a number of insights that church leaders must take to heart.

Part three provides a number of areas in which Christians need to engage and ways to engage with them. For example, taking the Bible seriously is a top priority and Christians need to know how to interact with the text. Of particular importance are the chapters on sex–which talks about porn addiction and same-sex attraction; and Christianity in the public square.

Morrow has peppered the book with brief interviews of leading Christian thinkers on a number of topics. While short, these interviews provide a number of great insights and will lead readers to explore many issues in greater detail. They range from “Leveraging the Internet to Make God Known” (with Randall Niles) to “Jesus Among World Religions” (with Craig Hazen), and beyond. Another helpful aspect are the lists of resources for further study, included at the end of each chapter. These include a list of books, DVDs, and websites for interested readers to explore.

There are few books that span as broadly as Think Christianly while also giving solid background discussions of each topic touched. Morrow continually provides valuable insights at a basic level which Christians can apply right now to start to “Think Christianly” about every aspect of life. If our churches and the members therein embrace many of the suggestions found in Morrow’s important book, we will be able to grow and positively impact the world in a major way. The book comes very highly recommended–it is the kind of book anyone involved in the church must have on their shelf and seek to apply to their lives.

I received a review copy of the book from Zondervan publishers. My thanks to Zondervan for the opportunity to review the book. I was not asked to write anything positive or negative about the book.

Think Christianly is available on Amazon (follow link) or at many local bookstores.

Book Review: “Where the Conflict Really Lies” by Alvin Plantinga

There are few names bigger than Alvin Plantinga when it comes to philosophy of religion and there are few topics more hotly debated than science and religion. Plantinga’s latest book, Where the Conflict Really Lies

There are few names bigger than Alvin Plantinga when it comes to philosophy of religion and there are few topics more hotly debated than science and religion. Plantinga’s latest book, Where the Conflict Really Lies (hereafter WCRL) has therefore generated much interest as it has one of the foremost philosophers of religion taking on this highly contentious topic.

Plantinga minces no words. The very first line of the book outlines his central claim: “there is superficial conflict but deep concord between science and theistic religion, and superficial concord and deep conflict between science and naturalism.”1

The first part of the book is dedicated to the superficial conflict between science and religious belief. The reason this alleged conflict is important is due, largely, to the success of the scientific enterprise. Because science has shown itself to be a reliable way to come to know the world, if religion is in direct conflict with science, then it would seem to discredit religion. Not only that, but, Plantinga argues, Christians should have a “particularly high regard” for science due to the foundations of the scientific enterprise on a study of the world.2

In order to examine this alleged conflict, Plantinga first takes on the article of science most often taken to discredit religion: evolution. Here, readers may be surprised to find that Plantinga does not try to argue against evolution itself. Rather, Plantinga draws a distinction between the notion of evolution and Darwinism. The former, argues Plantinga, is consistent with Christian belief, whether or not it is the way the variety of life came to be, while the latter is not consistent with Christianity because central to its account is the notion that the process of evolution is unguided.3

WCRL then turns to Richard Dawkins. Plantinga argues that “A Darwinist will think there is a complete Darwinian history for every contemporary species, and indeed for every contemporary organism.”4 Here again there is nothing which puts such a theory in conflict with Christian belief. Writes Plantinga, “[The process of evolution] could have been superintended and orchestrated by God.”5 But Dawkins (and others) claim that evolution “reveals a universe without design.” But what argument is provided towards this conclusion? Plantinga draws out Dawkins reasoning and shows that the only logic given is that evolution could have happened by way of unguided evolution. But then:

What [Dawkins] actually argues… is that there is a Darwinian series of contemporary life forms… but [this series] wouldn’t show, of course, that the living world, let alone the entire universe, is without design. At best it would show, given a couple of assumptions, that it is not astronomically improbable that the living world was produced by unguided evolution and hence without design. But the argument form ‘p is not astronomically improbable’ therefore ‘p’ is a bit unprepossessing… What [Dawkins] shows, at best, is that it’s epistemically possible that it’s biologically possible that life came to be without design. But that’s a little short of what he claims to show.6

Plantinga then moves on to argue that Daniel Dennett’s argument is similarly flawed.7 Paul Draper’s argument that evolution is more likely on naturalism than theism is more interesting, but assumes that “everything else is equal.”8 But then, everything is not equal. Theism provides a number of relevant probabilities which weigh the argument in favor of theism instead.9

The arguments against theism from evolution are therefore largely dispensed. What of the possibility of divine action? Some argue that God doesn’t actually act in the world—in fact, the argument is made that even most theologians don’t believe this, despite writing that God does act in various ways. The argument is made that because of natural laws, God cannot or does not intervene.10 However, one can simply argue that the correct view of a natural law is that “When the universe is causally closed (when God is not acting specially in the world), P.”11

Plantinga does acknowledge that there are some fields in science which do provide at least superficial conflict with theism. These include evolutionary psychology and (some) historical critical scholarship.12 Evolutionary psychology generally doesn’t challenge religious belief. “Describing the origin of religious belief and the cognitive mechanisms involved does nothing… to impugn its truth.”13 Now some suggest that religious beliefs are due to devices not aimed at truth, and this would provide a reason to doubt religious belief.14 However, the way that most do this is by conjoining atheism with psychology or operating under other assumptions which undermine religious belief a priori. While this may mean that specific conclusions in psychology are in conflict with theism, these conclusions only follow from the anti-theistic assumptions at the bottom. Thus, while some accounts of evolutionary psychology are in conflict with theism, they don’t provide a solid basis for rejecting it.15 Similarly, varied methods of historical concept may draw some conclusions which are in conflict with Christian theism, but these methods are themselves undergirded by assumptions that theism is, at best, not to be entered into historical discussion.16

There are, Plantinga argues, significant reasons to think that theism is in concord with science. First, the argument from cosmological fine-tuning, he argues, gives “some slight support” for theism.17 The section on fine-tuning has responses to some serious criticisms of such arguments. Most interesting are his responses to Tim and Lydia McGrew and Eric Vestrup—in which Plantinga argues that we can indeed get to the point where we can assess the fine-tuning argument;18 Plantinga’s discussion of the multiverse;19 and his discussion of relevant probabilities regarding fine-tuning.20

Michael Behe’s design theory is discussed at length in WCRL.21 Plantinga offers some additional insights into the Intelligent Design debate. He argues that one can view design not so much as a probabilistic argument but instead as simple perception.22 He reads both Behe and William Paley in this light and argues that they are offering design discourses as opposed to arguments.23 This, in turn, allows him to argue that design is a kind of “properly basic belief” and he offers a robust discussion of epistemology to support this intuition.24

Further, there is deep concord between Christian Theism and Science when one looks at the very roots of the scientific endeavor. Here, rather than simply listing various theists who helped build the empirical method, Plantinga argues that science relies upon various theistic assumptions in order for its methods to succeed. These include the “divine image” in which humans are capable of rational thought;25 God’s order as providing regularity for the universe;26 natural laws;27 mathematics;28 induction;29 and simplicity and “other theoretical virtues” (like beauty).30

Finally, Plantinga turns to naturalism: does it really resonate so well with science? Plantinga grants for the sake of argument that there is at least superficial concord between naturalism on science, if only because so many naturalists trumpet this “fact.”31 Yet there is, he argues, a deep conflict between science and naturalism: namely, that if evolution is true and naturalism is true, there is no reason to trust our cognitive abilities.32 “Suppose you are a naturalist,” he writes, “you think there is no such person as God, and that we and our cognitive faculties have been cobbled together by natural selection. Can you then sensibly think that our cognitive faculties are for the most part reliable?”33

Plantinga argues you cannot. The reason is because we have no way to suppose that evolution is truth aimed, but rather it is merely survival aimed (if indeed it is aimed at all!). He also argues that because naturalists are almost all materialists, there is no way to adequately ground beliefs.34 Finally, because naturalism and evolution conjoin to give a low probability that our rational abilities are reliable, we have received a defeater for every belief we have, including naturalism and evolution.35 Thus, the conflict “is not between science and theistic religion: it is between science and naturalism. That’s where the conflict really lies.”36

WCRL covers an extremely broad range of topics, and will likely be critiqued on each topic outlined above and more. The book touches on issues that are at the core of the debate between naturalists and theists, and as such it will be highly contentious. That said, the book is basically required reading for anyone interested in this discourse. Plantinga provides extremely valuable insights into every topic he touches. His discussion of biological design, for example, provides unique insight into the topic by locating it within epistemology as opposed to biology alone. Further, his “evolutionary argument against naturalism” continues to live despite endless criticism. The list of important topics Plantinga illumines in WCRL is extensive.

Where the Conflict Really Lies will resonate deeply with those who are involved in the science and religion discourse. Theists will find much to think about and perhaps new life for some arguments they have tended to set aside. Naturalists will discover a significant challenge to their own paradigm. Those on either side will benefit from reading this work.

——

1 Alvin Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies (New York, NY: Oxford, 2011), ix.

2 Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies, 3-4. (Unless otherwise noted, all references are to this work.)

3 12 (emphasis his).

4 15 (emphasis his).

5 16.

6 24-25.

7 33ff, esp. 40-41.

8 53.

9 53ff.

10 69ff.

11 86, see the arguments there and following.

12 129ff.

13 140.

14 141ff.

15 143ff.

16 152ff.

17 224.

18 205-211.

19 212ff.

20 219ff.

21 225-264.

22 236ff.

23 240-248.

24 248ff; see esp. 253-258, 262-264.

25 266ff.

26 271ff.

27 274ff.

28 284ff.

29 292ff.

30 296ff.

31 307ff.

32 311ff.

33 313.

34 318ff.

35 339ff.

36 350.

This review was originally posted at Apologetics315 here: http://www.apologetics315.com/2012/02/book-review-where-conflict-really-lies.html

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Contest: “How My Savior Leads Me” by Terri Stellrecht

Recently, I reviewed How My Savior Leads Me by Terri Stellrecht. I now have the opportunity to host a free book giveaway in which one winner will be selected to receive a copy of the book. I highly encourage readers to check out the book and Terri’s site, How My Savior Leads Me.

Recently, I reviewed How My Savior Leads Me by Terri Stellrecht. I now have the opportunity to host a free book giveaway in which one winner will be selected to receive a copy of the book. I highly encourage readers to check out the book and Terri’s site, How My Savior Leads Me.

Rules:

Those who wish to participate need only to post a question for the author of the book. The author and I will select a few questions for her to answer, and we will select the winning entry randomly from the total pool of questions selected. (All valid entries will have a chance to win, including those with questions not selected.)You Must Provide a Valid E-Mail Address To Be Selected As A Winner. Please note that only entries that ship to addresses within the Continental United States are eligible. Only one entry per person is allowed, but entrants can choose to enter more than one question should they desire.

“How am I supposed to know what to ask, if I haven’t read the book?”

Well, read the review to get some insight into the book, or check out the handy “look inside” feature on Amazon! Or, if you’re feeling particularly lazy: it’s a book which beautifully reflects on the passing of Trent, Terri’s son. She focuses upon God’s sovereignty and his plan throughout it all and rejoices in the fact that Trent is saved in heaven. So, questions can be asked on anything from divine sovereignty to Christianity generally to personal questions about coping with the loss of a child. But for more, I’d suggest reading the review.

The questions chosen to be answered will be featured following the contest in a follow up post, “Q and A with Terri Stellrecht.”

Any entry deemed offensive will be deleted. The contest will be open through midnight, central time, on February 19th, 2012. The winner will be selected by February 26, 2012.

Disclaimer:

This contest is being held at the sole discretion of J.W. Wartick and Terri Stellrecht. They reserve the right to cancel or amend the details of the contest in any way at any time. Specifically, they will not be held accountable if the book is lost in the mail; if an entry is missed; etc. In other words, this contest is in no way legally binding for any who participate. By submitting an entry, you agree to the stipulations and rules provided in this post.