Christianity

Book Review: “The Way of Dante: Going Through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven with C.S. Lewis, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Charles Williams” by Richard Hughes Gibson

The Way of Dante explores how Dante’s works influenced C.S. Lewis, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Charles Williams. Richard Hughes Gibson leads readers through an introduction to these thinkers, followed by a number of chapters highlighting each and how Dante inspired them.

Gibson leads readers across a wide array of topics related to these authors. The topics relate directly to the notions of hell, purgatory, and heaven (as noted in the book’s subtitle). Readers are presented with the writers’ wide array of thoughts and interactions on these topics, from reflections on the concept of hell to how a concept of the glory of heaven might be most adequately described.

By way of critique, I would note that I think the book is a bit in search of its audience. Gibson seems to assume at least some amount of background knowledge not just of Dante’s works but also of scholarship related to all of the authors mentioned. This assumption of background knowledge allows Gibson to dive into deeper themes more quickly, but can leave the reader feeling a bit lost without guidance. For example, a whole chapter dedicated to allegory notes not just the use of allegory in Dante, but also interplay between authors Sayers and Lewis on the topic of allegory. But readers are mostly left to their own devices to know the finer points of what the debate is even about. Also, because the book is exploring the interactions between three major Christian thinkers and Dante, there’s a necessary brevity to the points Gibson makes. But this brevity surely makes the book less useful to the scholar (the one with all the relevant background necessary to understand or know all the references being made) who may be looking for deeper insights. In short, the book leaves readers to dive into the deep end, sink or swim.

The Way of Dante touches on a lot of interesting themes. Readers will find quite a bit to digest here, though it can feel disorienting at times with the way the information is presented.

SDG.

Book Review: “Worth Doing: Fallenness, Finitude, and Work in the Real World” by W. David Buschart & Ryan Tafilowski

Worth Doing by W. David Buschart and Ryan Tafilowski explores the concept of “work in the real world” through a lens of fallenness and finitude.

The authors first introduce the concepts of finitude and fallenness, noting that their goal is to provide a theology of work for the “real world.” They use a few intriguing examples of how perspective can change attitudes related to workers. One is a comparison of the thoughts of both construction workers and office workers about the other–wishing they had what the other had not.

There are a few things that are notable for their absence. For example, there is little-to-no linkage of the concept of work to the capitalist system, nor are there critiques of unfettered capitalism and the exploitation of the worker. This, despite how neatly such a topic fits into the exploration. What could be more fallen than turning finite workers into mere numbers or cogs in the machine? The subject index, for example, doesn’t even have capitalism as a reference, while far more general terms (economics) or hyper-specific concepts (gig economy) get entries. Is it because there’s an avoidance of what could be a controversial critique of capitalism from a theological standpoint? I don’t know. What I do know is that the whole book seems to have such a topic looming in the background. When questions about how certain theologies of work might lead to the oppression of workers are right there and even being asked, the conspicuous absence of how capitalism can set up such an exploitation is all the more alarming.

The section on the goodness of work is another area where the critique of exploitative systems is notably so subtle as to be absent. Despite commenting on the goodness of work, it does so alongside the insights form Qoheleth (the teacher of Ecclesiastes). Even as discussing how everything is meaningless under the sun, the need for and even goodness of the harvest can be emphasized. Turning to the very end of the book, the authors urge readers to “still make hay while the sun rises” for creation is growning in need of redemption and renewal, but we must “come to terms with the kinds of creatures we are…” and that work, while “constrained… by finitude and haunted as it is by the curse, work is nonetheless a good gift from the good God and therefore worth doing” (195). I appreciate this ending note, though linked as it is with some of the discussion on vocation (see below) and the lack of critique of exploitative systems, it can feel a little empty or trite.

One section (190-193) has a scintillating discussion of the concept of “vocation” and how such a concept could be “easily put to exploitative use” through the notion of “doing what you love” (190). The authors call this a kind of “work mythology” that can use an “agency-dignity-power narrative” that “works well for those whose work is creative and satisfying” but perhaps not so much for those whose work is “degrading or unfulfilling” (190-192). Many scholars are referenced here–but one of the major thinkers on the concept of vocation, Martin Luther, is not. While the authors turn back on the concept of vocation and find some benefits, they do so in an explicitly theological framework that essentially sidelines the concept of work rather than integrating it into the concept of work. Here, Luther’s insights on the topic of vocation feel almost painfully absent. While the authors simply say that people were made for communion and union in Jesus Christ (193) and that “it is this; it is not a job or career or even a vocation” as the one thing we should be passionate about (ibid). Yet closing the discussion of vocation with this, moments after noting the lack of fulfillment that might be found in “degrading or unfulfilling” work reads almost as if the entire foregoing discussion on work and the “mythologies” involved in it is solved by a kind of “thoughts and prayers” response. Well, it’s one thing to have a job that we might feel is degrading; but worry not, our true fulfillment is found in union with Christ! Saying this is one thing; living it is another. And living it requires, ironically (based on the emphasis on “real world” in the subtitle), a more real world approach that has God entering into the world, entering into our suffering, and entering into our vocations.

The concepts of finitude and fallenness work well alongside discussions of work, and Buschart and Tafilowski are to be commended for bringing these insights alongside the concept of work. They do this alongside also finding the goodness of work. It’s a fine balance that the authors mostly navigate well (though, see above). Readers looking to start a theological exploration of work will certainly find plenty of depth to think on here.

Worth Doing is, well, worth reading if you’re interested exploring the intersection of theology and work. Readers of this review will, perhaps, think my thoughts are largely negative. But where I’m offering critique, I’m seeking more. There’s a wealth of information and topics to mine here, I just wish that some of them were turned to more incisive points made against what seems to be invisible problems lurking in the background. The book provoked quite a bit of thinking for me, and I believe it will for other readers, as well.

SDG.

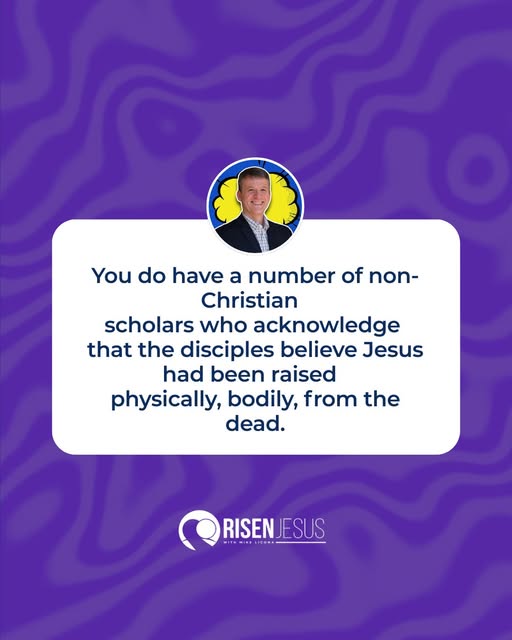

Sensationalism through banality in Apologetics and Counter-Apologetics- Be skeptical (with examples)

Sensationalism sells. We know this in basically every field. But when it comes to faith, unfaith, apologetics, and counter-apologetics, we need to be especially aware of this. Confirmation bias is a major thing and we often want to jump on or share things with which we agree. What’s especially surprising to me is how often apologists and counter-apologists sensationalize points that are actually extremely banal to anyone who has read almost anything in the related field. I wanted to share two recent examples of this, with some commentary on why it matters.

First, Christian apologist Michael Licona shared the image that I put leading this post. He writes, “You do have a number of non-Christian scholars who acknowledge that the disciples believe Jesus had been raised physically, bodily, from the dead.” Conversational tone aside (“you do…”), the point is mundane and would be obvious to just about anyone with any awareness of anything in the field. Licona doesn’t necessarily “sensationalize” this one, but the fact that it’s being shared in a block quote as if it’s some kind of revolutionary point in apologists’ favor is disturbing to me. With any such point, whether it’s pro- or anti-Christianity, there will be someone coming along to disagree, of course. The point I’m making isn’t that such naysayers don’t exist; it’s that they’re fairly obvious in their extreme bias against what are basically indisputable facts. That there were some disciples who believed Jesus was raised bodily from the dead is a pretty easily established thing in the Gospel narratives and coming from early church history as well. It’s not just unsurprising but obvious that even some who aren’t Christian would grant this.

Licona–whether intentionally or not–seems to be setting this quote up to imply a bigger point, though. Something like “and this supports the notion that Jesus actually did bodily raise from the dead” is an inference any apologist would want someone to make. And of course, in the narrowest sense, this is true. If Jesus did, in fact, raise from the dead, then having disciples who believed that would be a likely outcome. And having those beliefs demonstrated in at least one disciple provides some very minimal support to the notion that it might have actually happened (else where did that belief come from?). I’m not intending to start a debate over that here, what I’m trying to say is that it seems this fairly banal point is intended to make some bigger implication, and leaving it unstated disturbs me. I’d much rather an apologist just come out and make the argument. And, to be fair, this is just the style Licona has on his page: share a rather mundane quote from his works somewhere and let people infer and argue as much as they want about it in the comments. I think that’s a potentially misleading way of interacting, especially as an apologist.

An example from a counter-apologist standpoint was a recent video put up by Paulogia, who markets himself as “A former Christian takes a look at the claims of Christians, wherever science is being denied in the name of ancient books.” Paulogia, as Licona, makes some good points occasionally. But he’s also prone to sensationalizing points as if they’re something major, when they absolutely are not.

The recent video was entitled “Paul Wasn’t a Christian — The Shocking Truth From a Scholar.” With such a title, I was expecting… a shocking truth. Instead, the point made in the video is that [I paraphrase] “Paul wasn’t a Christian, because there was no Christianity to convert to. So he didn’t convert, he instead saw his beliefs as making Jesus part of his already existing Jewish faith.” I mean, of course that’s true. Anyone who has done even the slightest amount of studying the formation of Christianity would know this. Reading the Bible alone would fill one in on Paul being Jewish. It’s not some revelatory point.

But Paulogia stresses this numerous times in the video. When introducing the issue with the scholar he’s featuring (Dr. Paula Fredriksen), he even says that when he was a Christian this kind of point would have made his formerly Christian self “very uncomfortable.” Dr. Fredriksen chuckles and says “Oh dear, I don’t want to alarm anybody.” She’s just there sharing some great insights into the development of the early church, but Paulogia keeps pushing to make her points sensational. I think this is intentional in this case due to the “shocking truth” tagline. He wants to make it seem like these relatively obvious points about the early church are somehow “shocking” to Christians in a way that might make them deeply “uncomfortable.”

Now, I don’t want to deny that some Christians would likely find it uncomfortable to acknowledge that Paul wasn’t a Christian in the historical sense. But that point is… obvious. There was no Christianity in the broad sense to convert to, so having him build upon his Jewish foundation with a Jewish Messiah is completely unsurprising. Paulogia in the description even says the interview is “explosive” and that while apologists “have built entire arguments on Paul’s story” it’s possible that “their foundation is completely wrong.” I mean, come on. This is absurd to the extreme, and I’m kind of surprised that someone who’s as careful a thinker as Paulogia often seems to be would even frame this discussion in this way.[1]

So we have here two simple points being framed in ways that make them seem more than they are. I think we should not do that. Banality isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Making obvious points can be helpful to those who don’t already know them. But to then sensationalize the banal as if it is some major point that can shift a paradigm, that’s something that I think we need to be very careful about and quite skeptical of.

[1] I think Paulogia’s critique of Habermas’s work counting scholars, for example, is a somewhat crucial and destructive takedown. Also, Paulogia and Fredriksen discuss other points which may be deeply uncomfortable for very conservative Christians, such as how the Gospels differ (to the extent where Fredriksen says we might categorize some of it as historical fiction if written today) and the like. But even here Fredriksen answers Paulogia’s question about whether there’s anything we can take as reliable in the Gospels with a more positive review–we have to take some of it as a real basis for things that historically happened. Paulogia seemed briefly defalted by Fredriksen’s (I’ll use the word again) banal point. But come on, this is silly to even deny.

SDG.

The Suffering God and Impassibility in Bonhoeffer

“Only the suffering God can help”- Dietrich Bonhoeffer

The quote from Bonhoeffer is one of the most beloved and cited quotes of Bonhoeffer’s works. Bonhoeffer’s conceptualizing of God as a God who suffers is central to his Christology. But what does that mean related to the concept in classical theism of divine impassibility? Matthew Grebe’s essay, “The Suffering God: Bonhoeffer and Chalcedonian Christology” seeks to provide at least some way forward in this discussion.

Grebe’s essay centralizes the question: Is it theologically or biblically “correct to speak of the suffering God”? (138). Before diving into it, he outlines the notion of divine impassibility, with a look at church fathers and the Greek language behind impassibility. Classically, for example, Cyril of Alexandria notes that the suffering of Christ was only in regards to the human body, not to God, because God does not have a physical body. There is a kind of paradoxical theology present here, as the divine impassible is passible in the incarnate Word (141). Divine impassibility held that “God is not (negatively) affected by anything which transpires in God’s creation” (142).

Martin Luther’s concept of the communicatio idiomatum (the communication of attributes) contained in it a “protest” against divine impassibility (143). Thus, the attributes of the human are impacted by the divine and vice versa. However, Luther’s theology might be seen, in the abstract, to agree with patristic theology on the question of passibility (144)*. Bonhoeffer follows Luther in developing his concept of the humiliation of Christ and the suffering God (147). The Lutheran concept of condescension–God choosing to take on suffering and human attributes–is adopted by Bonhoeffer to discuss the notion of the suffering God. God’s suffering recontextualizes human suffering by having a “God who in Christ enters into suffering… [God] has changed sides to be in the place of those who are suffering, alongside those show suffer” (150). Because of this, human concepts of religiosity are challenged–“the religious person seeks an all-powerful God to help in [their] need… the cross shows that it is not possible to ‘appeal to an almighty God to intervene in our circumstances like a deus ex machina from the outside'” (151).

Thus, for Bonhoeffer, a truly “impassible god cannot really help humanity, as this god would be conceived of as distant and as a counter model to the world” (151). Therefore, God’s suffering “helps humanity” by forcing “human beings to take initiative, and stand autonomously and self reliantly. In a ‘world come of age’ Bonhoeffer suggests that we have to live… ‘as if there were not God.’ This means that instead of fleeing from the world, the individual is called to independent, responsible living before God, and with God, and yet simultaneously also without God. This independence brings about growth and development as she must live as one who manages her life without God… we need to learn to lie without the god of metaphysics, without the ‘working hypothesis of God’ who is omnipotent and always intervenes, knowing that the God of the Bible is with us… and guides us by his divine love.”

I especially found this last passage deeply edifying, as it presents the idea of religionless Christianity with much greater accuracy than I have often seen it. It’s not a rejection of God, but rather an invitation into responsibility before God, a God who suffers.

*Grebe notes that Luther himself would have objected to the focus on the concept of the abstract.

Inerrancy Undermines Interpretive Method?

James Barr’s work, Fundamentalism (1977) remains incredibly relevant to this day. I have been reading through it and offering up thoughts as I go. I’m reading the chapter about the Bible and Barr has enormous insight into the Fundamentalist (and here it is okay to substitute in “Evangelical”) reading of the Bible.

I’ve already written about how Barr notes that fundamentalists do not have a consistent hermeneutic of the Bible because their adherence to inerrancy forces them to read passages in light of their own understanding of truth. Barr isn’t done firing his salvoes at this issue, though he also notes that many people misread fundamentalists on their use of literalism:

“It is thus certainly wrong to say… that for fundamentalists the literal is the only sense of truth. Conservative apologists are right in repudiating this allegation. Unfortunately, the truth is much worse than the allegation that they rightly reject. Literality, though it might well be deserving of criticism, would at least be a somewhat consistent interpretative principle, and the carrying out of it would deserve some attention as a significant achievement. What fundamentalists do pursue is a completely unprincipled – in the strict sense unprincipled, because guided by no principle of interpretation – approach, in which the only guiding criterion is that the Bible should, by the sorts of truth that fundamentalists respect and follow, be true and not in any sort of error” (49).

Here Barr notes first that fundamentalists/evangelicals are right to push back against the accusation that they simply see literalism as the only way to read the Bible. However, he goes on to point out that their approach is significantly more problematic, because they eschew all principles of interpretation other than the one that the Bible should not be found to be in error on any point.

Who determines how to interpret any given passage, then, and how? Pontius Pilate asked “what is truth?” and has been lampooned time and again–but the question could be posed to conservative readers of Scripture, who, in their attempts to define truth, go to extraordinary lengths to massage the word into what they need it to mean to preserve the Bible (the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy is full of this). Who determines what is an error?

In my own life, I experienced this unprincipled–again, using the word technically as meaning literally without principle–approach to reading the Bible. At a Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod college, I was taught that we needed to use certain principles of interpretation, specifically those following a supposed “historical grammatical” method of interpretation. This method, among other things, aims at attempting to find the authors’ original intent in meaning in the Biblical text. Yet, when I pointed out that our knowledge of the thinking of the Ancient Near Eastern world meant that interpreting the passages which depict a flat earth with four corners seem to be the right interpretation, I was told that we suddenly didn’t follow a method that went to the authors’ original meaning. Another pastor told me very specifically that we couldn’t know the authors’ original intent in writing the words of Scripture, but the same pastor later countered my doubting of young earth creationism by claiming that the author of Genesis knew the Earth was young–and so intended us to believe so as well.

The shifting sand of interpretation would seem entirely odd if it wasn’t placed in the context of inerrancy, which is the tail that wags the dog. All conservative interpretation now centers itself around this new doctrine. Reading books about the Canaanite conquest from conservative scholars is telling in this regard, as are questions about exactly what happened with certain miraculous events in the Bible. The debates often center around just how far one can push inerrancy without it breaking. Can one say that the walls of Jericho didn’t literally fall to pieces after being marched around and shouted at a certain number of times and still hold to inerrancy? It seems silly, but this is a real debate that is happening in literature right now. The same question is asked, time and again, for any number of things–whether Jonah was really swallowed by a fish (or a whale?)–whether one has to affirm Job was a real person to affirm inerrancy. The questions in evangelical and conservative scholarship related to the Bible are so often not about what the text is actually teaching us but rather on what exactly is allowed to be said in the context of inerrancy. And when someone does do some serious hermeneutical work that pushes at a supposed boundary of inerrancy, they are inevitably called to account in conservative academic journals.

Inerrancy controls the narrative, it controls the hermeneutic, and it strangles the interpretation of the Bible. It ought to be abandoned.

Fundamentalism continues to provide fruit for thought, almost 50 years after its initial publication. I highly recommend it to readers.

SDG.

Bonhoeffer and Universalism?

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology is hotly debated to this day, from his views on pacifism to his stance on various ethical issues that face us now. One area that I haven’t seen discussed as much in Bonhoeffer scholarship is his view of universalism. Tim Judson’s recent work, The White Bonhoeffer: A Postcolonial Pilgrimage addresses Bonhoeffer’s stance on this doctrine in a short section. Judson’s insights are illuminating, showing that this is a topic fruitful for further discussion.

Judson notes, first, that the topic is grounded in Bonhoeffer’s theology of the cross and its universality. Second, Bonhoeffer’s thinking seems to be tied up in the ultimate stance of creation rather than individual salvation. Indeed he saw the hyper-focus on individual salvation as entirely the wrong starting point. Individual salvation isn’t the starting point, but rather something caught up in God’s working both through sacrament and the Cross. Third, this focus on the eschaton–the final end of creation–lead Bonhoeffer to brief defenses of the view of apokatastasis: the notion that all creation will have ultimate restoration. He defends this in Sanctorum Communio, for example, noting that “The strongest reason for accepting the idea of apocatastasis [alternate spelling of the Greek word] would seem to me that all Christians must be aware of having brought sin into the world, and thus aware of being bound together with the whole of humanity in sin, aware of having the sins of humanity on their conscience…” (DBWE 1, 286-287, cited in The White Bonhoeffer, 56). The universality of the sinfulness of humanity is, paradoxically, linked therefore to the hope for all humanity’s salvation in Christ. Bonhoeffer concedes this can only be a hope, not a certainty (ibid), but it seems his stance is in favor of the concept.

There are many things of interest in this brief analysis of Bonhoeffer’s universalism. The first is that there seems to be a connection between Lutheran soteriology and universalism, though that is not what Luther himself held. Lutherans explicitly hold to the cross as universally applicable. On the cross, God reconciled the whole world to Godself. If that’s true, then sin as the barrier between humans and God has been removed. As such, what can there be a reason for not having such reconciliation? A second point of interest is that Bonhoeffer sees soteriology as much more corporate- than individual-focused. This is something that is often difficult for theologians who come from backgrounds focused on individual salvation to understand, but it is a stance that I think is correct. The focus on individual soteriology has displaced the focus in Scripture which is on God’s work in Christ, not on an individual. None of this is to say that the individual is unimportant or not discussed in Scripture, but rather that the focus is mistaken when it is on the individual rather than the whole. Finally, Bonhoeffer’s view that we can have hope for final reconciliation, despite his own questions and affirmation of reprobation, lends itself to a very Lutheran stance of merely affirming what one finds in Scripture without trying to always reconcile potential paradoxes. (I have argued that a Lutheran non-rational stance can be taken for universalism in a post here.)

The White Bonhoeffer is a thought-provoking work overall. I am thankful to Judson for shedding light on so many intriguing topics. The book is recommended.

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Was Bonhoeffer “Lutheran or Lutherish” – a look at Michael Mawson’s essay

Michael Mawson’s Standing Under the Cross features several essays about Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology. It’s been a fascinating read. I was struck, however, by one essay that reads like an outlier. “Lutheran or Lutherish: Engaging Michael DeJonge on Bonhoeffer’s Reception of Luther” seeks to engage with Michael DeJonge’s Bonhoeffer’s Reception of Luther (reviewed by me here) and argue, at least in part, that there needs to be more complexity regarding Bonhoeffer’s relationship with Lutheranism than DeJonge presents. I found this essay an outlier–and perplexing–because Mawson himself cites Luther in conjunction with Bonhoeffer more than 20 times outside of this essay, which certainly lends itself to the interpretation of seeing Bonhoeffer as consciously Lutheran.

At the outset, I must note it is possible there is some subtlety to Mawson’s argument I’m missing. Following DeJonge, Mawson engages with Alasdair MacIntyre’s definitions of tradition, and draws from that a different conclusion–that Bonhoeffer should be approached to see “whether there are other, less determinate and more fluid ways of attending to this presence, of framing Bonhoeffer’s complex reception of Luther” (70). Interpreting this conclusion is difficult. Is Mawson saying that we need to view Bonhoeffer more along “Lutherish” lines than “Lutheran” ones–the latter being DeJonge’s claim? Or is he merely saying we ought to allow for broader influence on Bonhoeffer than Lutheranism?

If the latter, the point doesn’t actually seem to be outside of DeJonge’s purview either. While DeJonge certainly argues that Bonhoeffer is “consciously” Lutheran, that doesn’t preclude other influences. One can be Lutheran and still be influenced by and interacting with other authors of your own time. Mawson notes Hegel and Nietzsche as others with whom Bonhoeffer interacts (68). But again, this is hardly precluded by saying Bonhoeffer was Lutheran.

Mawson also makes some slight points about how Bonhoeffer refers to himself as Evangelical first, rather than Lutheran (67)–but the German Lutheran church referred to itself as Evangelical, anyway. Additionally, Mawson criticizes DeJonge for framing the debate as between Lutheran and Reformed positions. DeJonge’s complaint about scholars not paying enough attention to Bonhoeffer as Lutheran leading to misinterpretations of Bonhoeffer is counted by Mawson’s question: “does… the very existence of such diverse readings (and misreadings) itself complicate attempts to organize and stabilize Bonhoeffer theology as straightforwardly inside of ‘the Lutheran tradition’?” (69). I would argue that such diverse readings and misreadings does not do that at all. The fact that death of God theologians glommed onto Bonhoeffer’s works to extract “religionless Christianity” as meaning the same as “God is dead” hardly means we have to take as seriously the idea that Bonhoeffer might have believed God is dead as we do his stance on the theologia crucis (theology of the cross) which he consistently taught through his life. Diversity of opinion or interpretation does not entail diversity of the thing itself.

I already noted some confusion as well about Mawson’s own writings related to Bonhoeffer and Luther. Right before this essay, Mawson offered up two essays on Bonhoeffer’s view of Scripture and Bonhoeffer on discipleship, respectively, which heavily cite Luther in context of Bonhoeffer’s own view. Indeed, in the latter essay Mawson himself concludes by linking the theologia crucis with Bonhoeffer and Lutheranism specifically, not even bothering to distinguish between the Lutheran view and Bonhoeffer’s (see 58). Apart from all of this, though, looking at Bonhoeffer’s own works it becomes incredibly difficult to take seriously the notion that Bonhoeffer was anything but Lutheran. That doesn’t preclude him having other influences, advancing ideas that critiqued some parts of Lutheranism, or anything of the sort. But it does mean that reading Bonhoeffer correctly means reading him as a Lutheran pastor, which he was.

Just a few examples can serve to demonstrate Bonhoeffer’s deep commitment to Lutheranism. Bonhoeffer actively sought to catechize students within Lutheran traditions, including writing a catechism for students which closely followed Luther’s own catechism. Bonhoeffer’s discussion of the extra Calvinisticum includes a critique of Lutheran attempts to ground the counter to Calvinistic/Reformed doctrine in the concept of ubiquity precisely because Bonhoeffer argues that attempting to answer the Calvinist critique abandons the Lutheran answer which can simply be that Christ promised His presence and to leave it at that. Bonhoeffer defends infant baptism in more than one place in his works (for example in DBWE 14:829-830). He grounds the church on word and sacrament–the very way that Luther speaks of the church (again DBWE 14:829). He cites Luther more than any other theologian or scholar, and does so many, many times simply to settle the answer to a question such as saying [I paraphrase here] “Luther wrote [x]” and letting that settle the matter. He rarely critiques anything of Luther, rather citing Luther almost always in supporting a point or merely to cite something only to elucidate it afterwards. Mawson himself notes Bonhoeffer’s incredibly close interpretations of the theologia crucis–the very concept Luther wielded to differentiate himself from other theologians. Again, this isn’t a broader Christian concept but one that was explicitly and repeatedly taught and used by Martin Luther himself and one that Bonhoeffer cites again and again throughout his work such that it became the grounding for his notion that “only the suffering God can help.” Bonhoeffer doesn’t cite the Lutheran confessions as often as Luther, but when he does it is always done positively. For example, Bonhoeffer, after quoting the Formula of Concord, wrote: “The ‘expediency’ of any given church regulation is thus to be gauged solely by its accordance with the confessions. Only such accordance with the confessions is expedient for the church-community” (DBWE 14:704). How can one possibly read this passage, in which Bonhoeffer explicitly states that the way to judge a church regulation must be only in accordance to the Lutheran confessions–and he must mean Lutheran specifically because he just cited the Formula of Concord!

Examples could be multiplied ad nauseum, and DeJonge has done good work doing so, along with a handful of other authors who have put in the legwork to show that reading Bonhoeffer correctly means reading him as a Lutheran. I add my voice to this chorus, and as much as I enjoy Mawson’s work, I have to strongly question this specific essay. It is impossible to rightly interpret Bonhoeffer apart from realizing that he is Lutheran. And doing so does damage to his theology. None of this is to say other influences are impossible; it simply means that Bonhoeffer himself followed the Lutheran Confessions and Luther, even while engaging with them in a constructive way.

Standing Under the Cross continues to be a thought-provoking work that has led me to much reflection on Bonhoeffer’s theology–and my own. I recommend it.

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Markus Barth: His Life & Legacy” by Mark R. Lindsay

Markus Barth, son of the well-known theologian Karl Barth, was also a theologian. He is less-discussed and his legacy less well-established, but Mark R. Lindsay seeks to offer some corrective to that in Markus Barth: His Life & Legacy.

Lindsay offers this study in a work that is biographically and chronologically organized, but splits the focus with a look at Markus Barth’s theology and thought. What’s especially interesting is how Barth got caught up in controversies in Baptist and Reformed theology at his time, many of which touched upon events in the “real world” (read: life outside academic theology). For example, he criticized adoption of new Sunday School curricula as accommodation to coddling of children. While he didn’t use that very phrase, he was taken as being hyper-critical of children’s education in church, rather than the actual point he was making about integrating children into the life of the (adult) church as well. At other times, his views got him in hot water about various topics related to the Cold War (such as a divided Germany).

Barth also united his ethical-theological thought with the real world. His book, Acquittal by Resurrection argued that Christian ethical perspectives must be grounded in the Resurrection life of the church. This was doubly controversial due to his reliance upon the actual historicity of the Resurrection and the way he saw societal justice as being caught up in the theological narrative of the Bible (see 166-167).

One topic that occupied Barth at multiple points in his life was the Eucharist, which he taught in an anti-Sacramental way. He wrote on it as early as 1945, but returned to the topic in 1980. Then, he argued that because the Eucharist was a remembrance, it couldn’t be a Sacrament meant to be repeated. Despite his claim to go back to Scripture here, it is intriguing that Christ himself commanded his followers to “do this”–suggesting repetitive, Sacramental nature.[1]

Markus Barth: His Life & Legacy offers a solid look at the theology of Markus Barth. It’s unlikely the younger Barth will step out of the shadow of his father any time soon, but Lindsay offers some reasons to think that his theology should be explored as well. Whatever the topic, Lindsay offers a number of intriguing insights from Barth’s theology alongside contemporary events. It is a fascinating read that deserves careful study.

[1] I say this, of course, as a Lutheran with all the biases that entails. But I am admittedly baffled by Barth’s arguments here.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“Only a Suffering God can help” – Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Theologia Crucis

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology is heavily based upon the Theologia Crucis or the Theology of the Cross which he inherited from Martin Luther. H. Gaylon Barker’s The Cross of Reality is a book-length exposition of this important aspect of Bonhoeffer’s theology that brings an enormous amount of material and analysis to bear.

Barker’s analysis of Bonhoeffer’s theology of the cross is worth quoting at length:

“One problem… religion produces , from Bonhoeffer’s perspective, is that it plays on human weakness. In the world in which people live out their lives… this means a disjuncture or contradiction. Daily people rely on their strengths, in which they don’t need God. In practical terms, therefore, God is pushed to the margins, turned to only as a ‘stop-gap’ when other sources have given out. Then God, perceived as a deus ex machina, is brought in to rescue people. This, in turn, leads to the religious conception of God and religion in general as being only partially necessary; they are not essential, but peripheral. All of this leads to intellectual dishonesty, which is not so unlike luther’s description of the theology of glory. The strength of the theology of the cross, on the other hand, is that it calls a thing what it is. It is honest about both God and the world, thereby enabling one to live in the world without seeking recourse in heavenly or escapist realigous practices. Additionally, such religious thinking leads to the creation of a God to suit human needs… For Bonhoeffer and Luther, however, the real God is one who doesn’t appear only in the form we might expect, one whom we can incorporate into our worldview or lifestyle. God is one who is always beyond our grasp, but at the same time is a hidden presence in the world” (394).

Barker highlights Bonhoeffer’s own words to make this point extremely clear:

“[W]e have to live in the world… [O]ur coming of age leads us to a truer recognition of our situation before God. God would have us know that we must live as those who manage their lives without God. The same God who is with us is the God who forsakes us (Mark 15:34! [“And at three in the afternoon Jesus cried out in a loud voice, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?‘ (which means ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’)”]). The same God who makes us to live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God, and with God, we live without God. God consents to be pushed out of the world and onto the cross; God is weak and powerless in the world and in precisely this way, and only so, is at our side and helps us. Matt. 8:17 [“This was to fulfill what was spoken through the prophet Isaiah: ‘He took up our infirmities and bore our diseases.’] makes it quite clear that Christ helps us not by virtue of his omnipotence but rather by virtue of his weakness and suffering!” [388, quoted from DBWE 8:478-479]

Thus, for Bonhoeffer, God is not there as the divine vending machine, there to send out blessings when needed or called upon due to human inability. Instead, God enters into the world and by suffering, alongside us, helps us.

Bonhoeffer put it thus: “Only a suffering God can help.” Bonhoeffer, seeing the world as it was in his time, during the reign of terror of the Nazis, imprisoned, knew and saw the evils of humanity. And he knew that in seeing this, theodicy would fail. A God who worked only through omnipotence and only where human capacities failed was a God that did not exist. Instead, the God who took on our suffering and came into the world, who “by viture of his weakness and suffering” came to save us, is the only one who acts in the world–in reality.

Only a suffering God can help.

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Triune Relationality: A Trinitarian Response to Islamic Monotheism” by Sherene Nicholas Khouri

Triune Relationality: A Trinitarian Response to Islamic Monotheism is more than a modern work of Trinitarian theology in conversation with Islam. Khouri brings centuries of historical conversations on this topic to light in a survey of the history of Trinitarian and anti-Trinitarian arguments between these two faiths. This, alongside an appeal to modern analytic theology and the argument that theology based upon the Greatest Possible Being must inherently be relational.

The first four chapters of the book work to survey the history of the Muslim-Christian dialogue on Christianity. Modern tools are brought to this analysis, but it also provides excellent background on the arguments involved. It is only in the final chapter that Khouri turns fully to modern Christian answers to Muslim anti-Trinitarian apologetics.

Any topic of this specificity requires engagement with seemingly obscure points, but readers interested in the topic will find it a wealth of information. Where mileage will vary is on how much readers adhere to the use of analytic theology and whether they believe that arguments for the Greatest Possible Being have a place in theology.

Triune Relationality is a challenging, informative read. People interested in Trinitarian theology and, specifically, how it might come into conversation with Muslim apologetics for absolute monotheism should check it out.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.