Jesus Christ

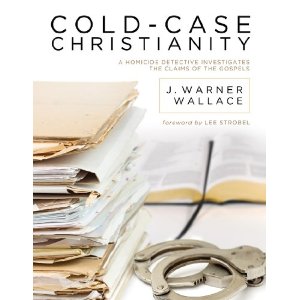

Book Review: “Cold Case Christianity” by J. Warner Wallace

I’ll forego the preliminaries here and just say it: this is the best introductory apologetics book in regards to the historicity of the Gospels I have ever read. If you are looking for a book in that area, get it now. If you are not looking for a book in that area, get it anyway because it is that good. Now, on to the details.

I’ll forego the preliminaries here and just say it: this is the best introductory apologetics book in regards to the historicity of the Gospels I have ever read. If you are looking for a book in that area, get it now. If you are not looking for a book in that area, get it anyway because it is that good. Now, on to the details.

Cold-Case Christianity by J. Warner Wallace maps out an investigative journey through Christian history. How did we get the Gospels? Can we trust them? Who was Jesus? Do we know anything about Him? Yet the way that Wallace approaches this question will draw even those who do not care about these topics into the mystery. As a cold-case homicide detective, Wallace approaches these questions with a detective’s eye, utilizing his extensive knowledge of the gathering and evaluation of evidence to investigate Christianity forensically.

He begins the work with a section on method. He argues that we must learn to acknowledge our presuppositions and be aware of them when we begin an investigation. Like the detective who walks into a crime scene with a preconceived notion of how the murder played out, we can easily fall into the trap of using our expectations about a truth claim to color our investigation of the evidence for that claim. Learning to infer is another vastly important piece of the investigation. People must learn to distinguish between the “possible” and the “reasonable” (34ff). This introduction to “abductive reasoning” is presented in such a way as to make it understandable for those unfamiliar with even the term, while also serving as great training on how to teach others to reason for those involved in apologetics.

Chapter 3, “Think Circumstantially” is perhaps the central chapter for the whole book. Wallace notes that what is necessary in order to provide evidence “beyond a reasonable doubt” is not necessarily “direct evidence.” That is, direct evidence–the type of evidence which can prove something all by itself (i.e. seeing it rain outside as proof for it actually raining)–is often thought of to be the standard for truth. Yet if this were the standard for truth, then we would hardly be able to believe anything. The key is to notice that a number of indirect evidences can add up to make the case. For example, if a suspected murderer is known to have had the victim’s key, spot cleaned pants (suspected blood stains), matches the height and weight a witness saw leaving the scene of the crime, has boots that matched the description, was nervous during the interview and changed his story, has a baseball bat (a bat was the murder weapon) which has also been bleached and is dented, and the like, these can add up to a very compelling case (57ff). Any one of these evidences would not lead one to say they could reasonably conclude the man was the murderer, but added together they provide a case which pushes the case beyond a reasonable doubt–the man was the murderer.

In a similar way, the evidences for the existence of God can add up to a compelling case for the God of classical theism. Wallace then turns to examining a number of these arguments, including the moral, cosmological, fine-tuning, and design arguments. These are each touched on briefly, as a kind of preliminary to consider when turning to the case for the Gospels. Furthermore, the notion of “circumstantial” or cumulative case arguments hints towards the capacity to examine the Bible and the Gospels to see if they are true.

Wallace then turns to examining the Gospels–Mathew, Mark, Luke, and John–in light of what he has learned as a detective. He utilizes forensic statement analysis as well as a number of other means by which to investigate witnesses and eyewitness reports to determine whether the Gospels can be trusted. He first turns to Mark and makes an argument that Mark had firsthand contact with Peter, one of the Disciples and an Apostle. He shows how we can search for and find “artifacts”–textual additions that were late into the accounts of the Gospels. None of these are surprises, because we know about them by investigating the evidence we have from the manuscript tradition. By piecing together the puzzle of the evidences for the Gospels, we form a complete picture of Christ (106ff).

It is easy to get caught up in “conspiracy theory” types of explanations for the events in the Bible. People argue that all kinds of alternative explanations are possible. Yet Wallace notes again that there is a difference between possible and reasonable. Simply throwing out possible scenarios does nothing to undermine the truth claims of the Gospels if the Gospels’ own account is more reasonable. Furthermore, drawing on his own knowledge from investigating conspiracy theories, Wallace notes that the Gospels and their authors do not display signs of a conspiracy.

A very important part of Cold-Case Christianity is the notion that we can trace back the “chain of custody” for the Gospels. By arguing that we are able to see how the New Testament was passed authoritatively from one eyewitness to disciple to disciple and so on, Wallace argues that conspiracy theories which argue the Gospel stories were made up have a much less reasonable explanation than that they are firsthand accounts of what happened. Much of the information in these chapters is compelling and draws on knowledge of the Apostles’ and their disciples. It therefore provides a great introduction to church history. Furthermore, Wallace notes that a number of things that we learn from the Gospels are corroborated not just by other Christians, but also by hostile witnesses (182ff). He also argues that we can know that the people who wrote the Gospels were contemporaries of the events they purported to report by noting the difficulties with placing the authors at a later date (159ff). This case is extremely compelling and this reviewer hasn’t seen a better presentation of this type of argument anywhere.

There are many other evidences that Wallace provides for the historicity of the Gospels. These include undesigned coincidences which interlink the Gospel accounts through incidental cross-confirmations in their accounts. I have written on this argument from undesigned coincidences before. Archaeology also provides confirmation of a number of the details noted in the Gospel accounts. The use of names in the Gospels place them within their first century Semitic context.

Again, the individual evidences for these claims may each be challenged individually, but such a case is built upon missing the forest for the trees. On its own, any individual piece of evidence may not prove that the Gospels were written by eyewitnesses, but the force of the evidence must be viewed as a complete whole–pieces of a puzzle which fit together in such a way that the best explanation for them is a total-picture view of the Gospels as history (129ff).

All of these examples are highlighted by real-world stories from Wallace’s work as a detective. These stories highlight the importance of the various features of an investigator’s toolkit that Wallace outlined above. They play out from various viewpoints as well: some show the perspective of a juror, while others are from the detectives stance. Every one of them is used masterfully by Wallace to illustrate how certain principles play out in practice. Not only that, but they are all riveting. Readers–even those who are hostile to Christianity–will be drawn in by these examples. It makes reading the book similar to reading a suspense novel, such that readers will not want to put it down. For example, when looking at distinguishing between possible/reasonable, he uses a lengthy illustration of finding a dead body and eliminating various explanations for the cause of death through observations like “having a knife in the back” as making it much less probable that accidental death is a reasonable explanation, despite being possible.

Throughout the book there are also sidebars with extremely pertinent information. These include quotations from legal handbooks which describe how evidence is to be viewed, explanations of key points within the text, and definitions of terms with which people may be unfamiliar. Again, these add to the usefulness of the book for both a beginner and for the expert in apologetics because it can serve either as a way to introduce the material or as helpful guides for using the book to teach others.

Overall, Cold-Case Christianity is the best introduction to the historicity of the Gospels I have ever read. I simply cannot recommend it highly enough. Wallace covers the evidence in a winsome manner and utilizes a unique approach that will cause even disinterested readers to continue reading, just to see what he says next. I pre-ordered two copies to give to friends immediately. I am not exaggerating when I say that this book is a must read for everyone.

Links

View J. Warner Wallace’s site, Please Convince Me, for a number of free and excellent resources. I highly recommend the blog and podcast.

I would strongly endorse reading this book alongside On Guard by William Lane Craig–which thoroughly investigates the arguments for the existence of God. With these two works, there is a perfect set of a case for Christianity.

Source

J. Warner Wallace, Cold-Case Christianity (Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook, 2013).

Disclosure: I received a copy of the book for review from the publisher. I was not asked to endorse it, nor was I in any way influenced in my opinion by the publisher. My thanks to the publisher for the book.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Jesus’ Birth: How undesigned coincidences give evidence for the truth of the Gospel accounts

There are many charges raised against the historicity of the birth narratives of Jesus Christ. These run the gamut from objections based upon alleged contradictions to inconsistencies in the genealogies to incredulity over the possibility of a virgin birth. Rather than make a case to rebut each of these objections in turn, here I will focus upon using undesigned coincidences to note how these birth narratives of Christ have the ring of truth. How exactly do undesigned coincidences work? Simply put, they are incidental details that confirm historical details of stories across reports. I have written more extensively on how these can be used as an argument for the historicity of the Gospels: Undesigned Coincidences- The Argument Stated. It should be noted that the birth narrative occurs only in Matthew and Luke. John begins with a direct link of Christ to God, while Mark characteristically skips ahead to the action. Thus, there are only a few places to compare these stories across different reports. However, both Mark and John have incidental details which hint at the birth account. These incidental details lend power to the notion that the birth narratives of Jesus are historical events.

There are many charges raised against the historicity of the birth narratives of Jesus Christ. These run the gamut from objections based upon alleged contradictions to inconsistencies in the genealogies to incredulity over the possibility of a virgin birth. Rather than make a case to rebut each of these objections in turn, here I will focus upon using undesigned coincidences to note how these birth narratives of Christ have the ring of truth. How exactly do undesigned coincidences work? Simply put, they are incidental details that confirm historical details of stories across reports. I have written more extensively on how these can be used as an argument for the historicity of the Gospels: Undesigned Coincidences- The Argument Stated. It should be noted that the birth narrative occurs only in Matthew and Luke. John begins with a direct link of Christ to God, while Mark characteristically skips ahead to the action. Thus, there are only a few places to compare these stories across different reports. However, both Mark and John have incidental details which hint at the birth account. These incidental details lend power to the notion that the birth narratives of Jesus are historical events.

Joseph

First, there is one undesigned coincidence that is such a gaping hole and such a part of these narratives most people will probably miss it. Namely, what in the world was Joseph thinking in Luke!? Do not take my word for this–look up Luke chapters 1-2. Read them. See anything missing? That’s right! Joseph, who is pledged to a virgin named Mary (1:27) doesn’t say anything at all about the fact that his bride-to-be is suddenly pregnant. There is no mention of him worrying at all about it.

So far as we can tell from Luke, Joseph, who we only know as a descendant of David here, is going to be wed to a virgin and then finds out that she’s pregnant. He’s not the father? What’s his reaction? We don’t find out until Luke 2, where Joseph simply takes Mary with him to be counted in the census, dutifully takes Jesus to the Temple, and that’s about it. Isn’t he wondering anything about this child? It’s not his! What happened?

Only by turning to Matthew 1:18ff do we find out that Joseph did have his second thoughts, but that God sent an angel explaining that Mary had not been unfaithful, and that the baby was a gift of the Holy Spirit. So we have an explanation for why Joseph acted as he did in Luke. Now these are independent accounts, and it would be hard to say that Luke just decided to leave out the portion about Joseph just because he wanted to have Matthew explain his account.

The genealogies of Jesus that Matthew and Luke include are different, but they reflect the meta-narratives going on within each Gospel. Luke’s narrative generally points out the women throughout in a positive light, and it is often argued that his genealogy traces the line of Mary. Matthew, writing to a Jewish audience, traces through Jesus’ legal father, Joseph. Now it could be argued that these are simply reflections of the authors’ imaginations within their fictional accounts, but surely including names with descendants tracing all the way back to Abraham and beyond is not a good way to construct a fictional account. No, Matthew and Luke include the genealogies because their accounts are grounded in history.

Incidental Details

Interestingly, the birth narratives of Jesus also help explain the events reported in Mark and John, which do not report His birth. What of the apparent familiarity John had with Jesus in Mark 1:3ff and John 1:19ff? It seems a bit odd for John to go around talking about someone else “out there” who will be better in every way than he himself is without knowing who this other person is. Well, looking back at Matthew and Luke, we find that Mary and Elizabeth (John’s mother) knew each other and had visited each other during their pregnancy. It seems a foregone conclusion that they continued to interact with each other after the births of their sons, which would explain John’s apparent familiarity with Jesus in Mark and John.

Strangely, Mark never mentions Joseph as Jesus’ father. If all we had was Mark’s Gospel, we would be very confused about who Jesus’ father is. The oddness is compounded by the fact that Mary is mentioned a number of times. Well okay, that still seems pretty incidental. But what about the fact that Mark explicitly has a verse where he lists Mary as well as Jesus’ siblings?

Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon? And are not his sisters here with us?” And they took offense at him. (Mark 6:3, ESV)

This verse seems extremely weird. After all, Joseph was a carpenter (well, a more accurate translation is probably “craftsman”) and yet despite Mark explicitly using that word for Jesus, as well as listing Mary and Jesus’ siblings, we still see nothing but silence regarding Jesus’ father. Well, of course! After all, when we turn to the birth narratives in Matthew and Luke, we find that Jesus was born of a virgin. Jesus had no human father. Thus, Mark, ever the concise master of words, simply omits Joseph from details about Jesus’ life. But to not mention Jesus’ father in a largely patriarchal society alongside his mother and siblings seems extremely strange. It is only explained by the fact of the virgin birth, with which Mark would have been familiar. However, Mark didn’t see the birth narrative as important in his “action Gospel.” Only by turning to Matthew and Luke do we find an explanation for the strange omission of Joseph from Mark’s Gospel.

Conclusion

I have listed just a few undesigned coincidences to be gleaned from the birth narratives of Jesus. The fact of the matter is that these can be multiplied almost indefinitely if one looks at the whole of the Gospels, and even moreso if one investigates the whole Bible. These incidental details fit together in such a way as to give the Gospels the ring of truth. The way that Matthew fills in details of Luke, Mark demonstrates his familiarity with the birth narratives, and the intimate connections of Jesus and John are all cross-confirmed is both incidental and amazing. The claim is not that based upon these incidences alone the Gospel accounts are true. No, the claim is that those who challenge the truth of these accounts must account for these incidences in a way that is more plausible than that they simply occur when people relate history. It seems that the only way to do that would be to resort to outlandish narratives that involve the four authors sitting together and discussing which portions of stories to leave out so the others can fill them in. No, instead it seems much more likely that these four authors were writing what they had witnessed–or received from eyewitness testimony, and just as we do when recounting events (think of 9/11, for example, and the different things people remember) they wrote specific details they felt were important or part of the narrative, while the others found other things more important or had other incidental knowledge related to the events they recorded.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

A Christian look at “John Carter”

Disney’s “John Carter” is based off a series of science fiction novels by Edgar Rice Burroughs which originated in 1912 and helped shape the genre. I admit I have not read the books–though I now plan to–so I can’t comment on how closely the movie adheres to the storyline of the novels. As always, there will be spoilers for the movie. I have left the outline of the plot out of this post, but as usual a succinct summary can be found on wikipedia.

Heroism and Just War

John Carter is a hero with a haunted past. The movie, unfortunately, never really explores his history much. From what I could tell, he went to war and came back to find his family had all been killed and his house burned as part of the conflict. He thus swore off fighting for a cause and instead decided to seek his fortune.

Once Carter reaches Mars (Barsoom), however, he is thrown into a conflict in which he realizes that the fate of an entire planet rests upon the victory of the city of Helium. Once he realizes the implications of this battle (and conveniently, finds the princess of Helium particularly attractive) Carter aligns himself with the Tharks, a race of aliens largely viewed as savages by the humanoid aliens on the planet. He is able to seal victory for Helium by making the Tharks realize that they, too, have a place on Barsoom which is influenced heavily by the conflict between Helium and Zodanga.

The movie touches, then, on the notion of a just war. Helium is trying to save the planet, while Zodanga does little but consume and subjugate. The Tharks view both sides as neutral and prefer them to continue fighting, as long as the war stays away from them. Yet it becomes clear that due to the influence of the Thern–an extremely advanced (technologically speaking) race which seeks to orchestrate the destruction of planets–that the conflict has implications for everyone on Barsoom, and indeed, on Earth.

Sin

The Tharks have a tradition in which they brand their people as punishment for their sins. The brands are placed so that they continue to cover one’s skin throughout their lives. If one has committed enough offenses that there is no longer any place for a branding, then one is either killed or thrown into the arena to fight against impossible odds. One’s sins literally cover their flesh. One cannot escape from one’s offenses. There is no redemption.

Christianity affirms that sin is something for which one can make no redemption for themselves. One’s sins are, in a sense, branded onto one’s past. Only by repentance and grace through faith can one be saved. There is no escape from one’s offenses except through the full and free forgiveness through Jesus Christ our Lord. There imagery in the movie of one’s sins being displayed on one’s flesh is powerful, and it resonates with the Christian view that our sins condemn us forever. Only by grace can we be saved. There is no removing the sins–branded onto us–by our own power.

Religion

The Therns are supposedly oracles of the goddess. However, it turns out that they are actually dedicated to manipulating civilizations across the galaxy. It is never discussed whether the goddess and the Therns were ever actually genuine, but it seems fairly clear that those calling themselves Therns are just using the title in order to gain power.

Religion is therefore seen as a kind of way to manipulate and enthrall the masses. All of the sides of the conflict are shown to be dedicated to the goddess, but none seems to have the full truth. However, it does seem that the dedication of the Tharks, in particular, shows a resonance with truth and a genuineness that reaches beyond the mere use of religion as subjugation. The movie, I would say, gives an overall neutral view of religion. In some ways it can be used for ill, but it nonetheless is not inherently evil.

Yet another aspect of religion in the movie, however, is that one can observe the difference between genuine faith and exploitative faith. It is clear that many of the Therns genuinely believed in the goddess and there are scenes which convey a sense of awe over the faith on Barsoom. Religious practice is seen as taking place on a genuine level and being an important part of the lives of the practitioners. These religious persons are seen as genuine and largely trustworthy. On the other hand, those who seek to exploit the faith are seen as inherently evil. Such a view should resonate with Christians, who are instructed to be aware of those within the church who would seek to lead us astray (antichrists).

Alien Life and social (in)justice

Alien Life and social (in)justice

Social justice is an underlying theme in the movie. By portraying the alien Tharks as the outsiders, the movie is able to focus on the notion that the downtrodden and overlooked can rise above the limitations of their position. Although viewed as unequals, they are equals.

One poignant scene early in the film showed a hatchery for the Tharks. They came to collect the hatchlings and it turned out that some eggs hadn’t yet hatched. The Tharks then fired on all the eggs with their gun and destroyed the “weak” young. I couldn’t help but think that this is largely what is happening in the real world with abortion [a topic I have written on extensively].

Here again, worldviews rear their ugly heads. The faith of Barsoom is a bit enigmatic. The goddess seems largely uninterested in the goings-on of everyday life. Furthermore, those who follow her are fully willing to kill their own young in order to ensure the survival of the strongest. One can’t help but think of the prioritization of desires over objective morality in our own world.

Conclusions

The film was a lot of fun. One can easily see how the source material influenced science fiction in a number of ways. As a huge fan of science fiction, I can’t help but love the movie. It is so awesome to see the origins of sci-fi play out on screen. Christians watching the film will find areas to discuss social justice, just war, and heroism. Furthermore, there are some poignant scenes which can bring up issues related to abortion and racism. A final talking point would be to discuss religion as a transcultural entity and see how it has been used in both good and bad ways. I go into this issue in my own post on the “Myth of ‘Religion.'”

“John Carter” is another film with a number of worldview discussions happening in the background and it’s worth a watch both in order to start discussions about religion, justice, and the like but also to explore the origins of science fiction, a genre steeped in religious dialogue.

Links

Check out another review of the movie over at Sci-Fi Christian, which looks into the background of the movie more, as well as exploring some Bible texts in relation to the movie: Barsoom or Bust!

Engaging Culture: A brief guide for movies– I discuss how Christians can view movies with an eye towards worldview.

Religious Dialogue: A case study in science fiction with Bova and Weber– I look at how science fiction is frequently used to discuss worldviews and analyze two major authors in the field along with their view of religious dialogue.

Alien Life: Theological reflections on life on other planets– What would it mean for Christianity if we discovered life on other planets?

Check out my other looks at movies, including the Hunger Games and the Dark Knight Rises here (scroll down for more).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“The Dark Knight Rises”- A Christian Reflection

The epic tale begun with Batman Begins

The epic tale begun with Batman Begins and continued with The Dark Knight

comes to a fruition in The Dark Knight Rises

. Batman has always been my favorite hero (I say hero and not superhero because he has no superpowers), and I couldn’t wait to see the finale to the trilogy I had been awaiting for some time. It didn’t disappoint. Herein, I reflect from my Christian background on the many themes in the movie.

Here’s the last warning: THERE ARE SPOILERS HERE. BIG ONES.

I’m going to eschew giving a plot summary because what I want to contribute to the conversation is a discussion on the themes. If you don’t feel like bothering with the movie, it would be good to at least know about the plot before reading this post. Check here for a brief summary.

Faith

Throughout the movie I kept noticing faith as a major theme. There were those who had maintained faith in a lie: Harvey Dent. Batman had taken the fall for him in The Dark Knight in order to provide Gotham with a needed hero. This faith was misplaced, and Jim Gordon, the police commissioner of Gotham City, almost destroyed himself keeping it inside himself. He said, at one point, “I knew Harvey Dent. I was his friend. And it will be a very long time before someone… Inspires us the way he did. I believed in Harvey Dent.” Yet the whole time Gordon knew he was speaking a lie. He believed in Dent, but he no longer believes in him.

Batman placed his faith in Catwoman/Selina Kyle. He firmly believed that there was more to her than the anger she continually expressed. This interplay was made more interesting by the interaction between Batman’s and Catwoman’s alter egos, Bruce Wayne and Selina Kyle. Selina Kyle, who seemed generally upset with all the rich and famous in Gotham and the decadence found therein–told the rich billionaire Bruce Wayne, “You think this can last? There’s a storm coming, Mr. Wayne. You and your friends better batten down the hatches, because when it hits, you’re all gonna wonder how you ever thought you could live so large and leave so little for the rest of us.” More on the interaction between the two later.

Alfred put his trust in Bruce Wayne. He strongly wanted Wayne to have a satisfying, fulfilling life, and throughout the film he worried that Batman would destroy Wayne. When push came to shove, Alfred was willing to leave Wayne in order to try to save him. Again, more on this later.

Finally, there were those who had faith in Batman. Batman, to them, was more than just a hero, he was a symbol of hope and justice.

One thing viewers should note is that the use of “faith” in The Dark Knight Rises is not some kind of hack definition. It doesn’t mean “belief in the face of insurmountable evidence to the contrary” or “belief in something you know ain’t true.” Instead, faith in the movie is faith in–a trusting faith based on evidence. Those who believed in Harvey Dent were mistaken, but that wasn’t due to evidence, it was active deception. Batman’s faith in Selina Kyle was firmly based on his ability to read her character. Others’ faith in Batman was based upon either a personal knowledge of the secret (Gordon) or knowledge of his actions as Batman (John Blake, others). It is very similar to the faith of the Christian, which is based upon knowledge.

The most obvious theme in the movie was that of “arising.” Bruce Wayne had to overcome his doubts, fears, and become something greater. Yet he had to rely on others to build this journey. The knowledge of his fellow prisoners in ‘the pit’–a prison into which people were thrown, but could climb out. Only one had ever managed it, however, and that was Ra’s Al Ghul’s daughter, who had subsequently saved Bane. Ironically, then, the rise of his enemies forced the Dark Knight to meet their challenge. He had to transcend his limits and become that which Gotham needed in order to save it.

Yet Batman/Wayne wasn’t the only one who rose in the movie. Selina Kyle also experienced a major transition. As a character, she was initially powerfully motivated by anger and a desire to escape. She was portrayed as being very frustrated and angry with the social imbalance of the world and determined to not only try to balance it–in her favor, of course–but also to punish those who made it so imbalanced. When Batman returns to Gotham after his exile by Bane, he confronts Selina. He points out that the storm she predicted earlier has hit, and it doesn’t seem like it was what she wanted. Still, however, she seems determined to be in it all for herself. Yet ultimately she comes back to fight with the Dark Knight against the evil powers that are trying to destroy Gotham. In the end, she does manage to rise, with the guidance and help of Bruce Wayne/Batman.

John Blake–the incorruptible cop–also rose. It is revealed shortly before the film’s end that he is Robin–and that he is about to take up the cowl of Batman, to become the symbol for Gotham. Here, I sensed a feeling of fulfillment. We encourage others to walk in our shoes and left them up when they are down. Without Batman, Blake would not have survived. Yet he goes on to [presumably] become the next Batman, to save others.

Corruption

The world is not all sunshine and daisies. The world is full of corruption and sin. Interestingly, The Dark Knight Rises has much less corruption on the part of the police force than the previous movies. The turn was a noticeable, perceptible shift. As far as the plot goes, I wonder if any of that was due to the “Dent Act” which effectively ended organized crime in Gotham. Despite the relative “cleanness” of the police force, however, there was plenty of corruption to go around. Once Bane overthrows the city, there are “people’s courts” where “justice” is dole out on those already deemed guilty. The prisons are ripped open due to the lie [Harvey Dent] that many were imprisoned by. One wonders, how much of this is justice? Is any of what Bane says true?

Furthermore, it is a powerful reminder of the human condition. Given the chance to rule themselves, Gotham erupted into violence and brutality. It is little wonder that this should happen, given a Christian worldview, because all are sinful and need grace. All deserve justice.

Justice and Freedom

Is there justice? Was Batman just in continuing his adventures as the Caped Crusader? Is violence ever a justifiable means to an end?

Within Christianity there is a long history–traceable to Augustine, at least–of the concept of a “Just War.” There will be much debate over whether the actions of someone like Batman could be justified. Is it ever permissible to take justice into one’s own hands? I leave the question open.

Yet more important questions loom. What is justice? Who is to determine it?

One wonders what worldview could plug these holes that continue to open as human nature is probed by director Christopher Nolan throughout the Batman Trilogy. From the irrational desire to cause fear and anarchy of Scarecrow to the anarchist nihilism of the Joker to the over-reactive retribution of Bane, Nolan has exposed viewers to the depths of human freedom. What price, freedom? Bane tells Gotham he has set them free, yet he has truly imprisoned them by their own nature. What occurs is a vivid portrayal of human nature and destruction.

Christian Threads- Redemption and Cleansing

Christian Threads- Redemption and Cleansing

I can’t help but think of Bruce Wayne’s ascension from the pit to the chants of “rise” without thinking of the Christian faith. We sinners are in our own pits of sin. Yet just as Wayne we have a very real lifeline. Yes, Bruce Wayne shunned the physical lifeline, but he clung to an idea: he clung to faith. Similarly, the Christian shuns the physical realm and is saved by faith. Rise.

There is the notion of a “clean slate.” Selina Kyle is primarily motivated by her desire to have such a clean slate. She wants to start over. Batman offers it as a tantalizing price to pay for her help in the final battle. Yet in the end, Selina comes back and redeems herself more than was required by the Bat. At the end of the movie, however, it is revealed that both Bruce Wayne and Selina Kyle have managed to use the “clean slate.” They have started afresh. Again, a Christian allegory or overlay could be applied here. We are all sinners in search of a clean slate, yet we cannot provide it for ourselves. While have no nearly-magical technology to give us a clean slate, we do have salvation by grace through faith. And that, my friends, is something worth considering.

Finally, Wayne’s “rise” coincides with the need I described earlier. The fact that enemies had arisen meant that Batman had to also rise to the challenge. Christians know that once sin came into the world, the only way to cure it would be for God to come into the flesh to save us. Such is poignantly portrayed when Jim Gordon talked to John Blake. Gordon talks about the evils of Gotham and describes how Batman transcends the filth, but he “puts his hands into the filth [with us]” [I believe he says filth, but I have a suspicion it may have been muck–correct me if I’m wrong here]. Wayne, though having no obligation to these people, still loves Gotham, and he is willing to condescend to get his hands dirty–to put his hands into the filthy muck and dirty them in order to save it. Is it an allegory? It certainly works as one. Jesus is God incarnate. A God who loved His creatures so much that He was willing to become one of them–to put his hands into the filth and reach down to save us. Just as Batman did what was necessary to save while also dealing justice, Christ did what was necessary in order to save humanity from its own sin. The Son Rises.

Links

Check out more of my reflections on movies. If you liked The Dark Knight Rises, check out my look at The Avengers.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Ehud the Judge/Assassin

Ever notice that the Bible is like an action movie? There are some seriously amazing stories in the Bible. Judges is full of them. Some of these stories can really make people think, whether they believe the Bible is the Word of God or not.

Ever notice that the Bible is like an action movie? There are some seriously amazing stories in the Bible. Judges is full of them. Some of these stories can really make people think, whether they believe the Bible is the Word of God or not.

Take Ehud. His story would make a really awesome action movie. It’s recounted in Judges 3:12ff. Here are the highlights:

The Israelites sin. The LORD punishes them by sending Eglon, King of Moab. Eglon gets some allies of his to come with him and they beat up Israel. The Israelites cry out for help, and the LORD sends help for them. Enter Ehud, the assassin. Ehud is left-handed, and the king’s body guards don’t discover his weapon (probably because they didn’t bother to search his right side–his sword would be on opposite hand to make it easier to draw). Ehud asks for a private audience and Eglon grants it. Ehud stabs Eglon so hard that it sinks all the way into the portly man’s flesh. Leaving his blade behind, Ehud escapes and rallies the troops, who unite around their new leader. He then strikes ten thousand Moabites down with his army, and none escape.

Yeah, it could make a pretty epic action movie. But what about a Bible story? How are we supposed to take this story in the context of Scripture? Note once more the beginning of the story: the Israelites did evil (Judges 3:12). Throughout Judges, we see the same pattern: the Israelites do evil, and God punishes them by oppressing them with one of the nations in the area. Then, the Israelites realize their evil, and they cry to God, repentant, and ask Him for help. He delivers them from their enemies, and there is peace in the land.

What can we take away from this story? Does it show another instance of evil in the Bible which Christians must hide? No, rather it shows the story that we can see woven throughout the Scriptures: a story of redemption and peace with God. Because of Jesus, we now live in an era in which we no longer have to wait for a deliverer, as Israel did. We’re told that all people have sinned and fall short (Romans 3:23), just as the Israelites did. And we all deserve punishment. But when we cry out to God, we know there is a redeemer close at hand. God forgives our sins because of Christ, and we can live in peace.

The cycle in Judges is repeated over and over. It reflects a time in which everyone did what they willed (Judges 21:25). God came to His people with the understanding they had. But in our time, we have Jesus who died once for all. The cycle is broken, and we may enjoy eternal peace.

See Judges 3 for more on Ehud.

This is part of a continuing series on “Awesome Person(s) of the Bible.” Other posts can be found here.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.