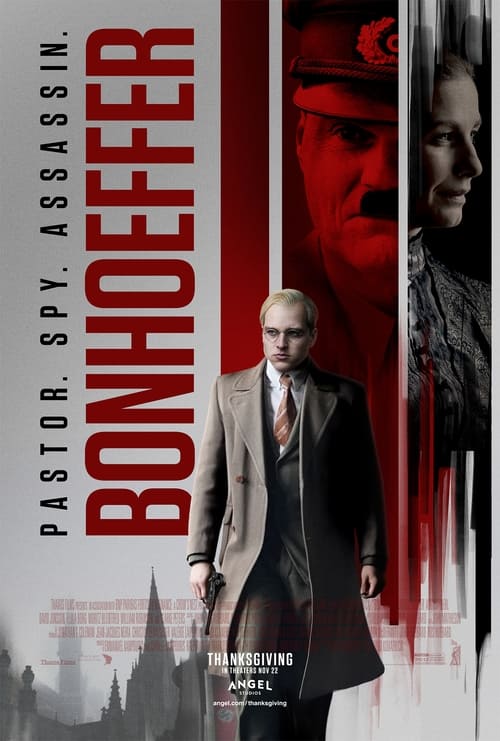

Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Spy, Assassin is, ostensibly, a film about the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German pastor and theologian who was murdered by the Nazis. Bonhoeffer’s works have been incredibly formative in my own life and faith formation. I’ve read and reread his works for over a decade, and I was incredibly excited to see an attempt to make his life into a blockbuster film. That being said, the movie was a great disappointment. It is important to discuss why and how it was disappointing, though, because I think that matters.

First, I think biopics almost always have to fudge on details and stories. That’s fine. Often, for the sake of time, films have to combine life events together, omit details, and tell aspects of one’s life in a more interesting (read: usually action packed) way in order to keep the movie flowing. I am not planning to critique the movie (much) for this apart from where it is necessary.

The most important critique I want to offer of the film, though, is that it turns Bonhoeffer’s life into something that is at its core, almost entirely pointless. In the movie, Bonhoeffer is arrested for attempting to kill Hitler (not historically accurate) and at his execution, that’s the reason (along with money laundering) that he is executed. But in the movie, Bonhoeffer’s alleged involvement in the plot to assassinate Hitler amounts to virtually nothing. This is what is actually depicted in the movie: 1. Bonhoeffer agrees with his brother-in-law Hans Dohnanyi to join violent resistance against Hitler, over the protestations of his friend Eberhard Bethge that he should remain committed to pacifism; 2. he prays with a guy who’s going to wear a bomb to try to kill Hitler; 3. he is asked by Dohnanyi to try to get a bomb from Churchill and fails. What exactly was this supposedly heroic act that Bonhoeffer did, according to the movie’s own narrative arc that makes him so incredibly amazing? What makes him into this wonderful martyr or hero of the resistance? Nothing, according to the movie. He barely had even tangential awareness of what was happening in the attempt to kill Hitler, even according to the film. But because the film makes that the central aspect of Bonhoeffer’s life, the culmination of his theological work, it drains Bonhoeffer’s life and theological work of its actual power. And because the assassination attempt was manifestly not the central aspect of Bonhoeffer’s actual life, the film struggles to shoehorn it in and then fails to even make that interesting.

The film thus turns Bonhoeffer’s life into a pointless footnote. It is Dohnanyi who is the real hero of the Bonhoeffer movie, a man who infiltrated the Abwehr, worked to save Jews, acquired the bomb, and planned the assassination attempt. Bonhoeffer did what? He prayed for the success of the mission? How does that make him into an interesting character?

The real parts of Bonhoeffer’s life that make his story so vital or interesting are, somewhat ironically, either glossed over or modified so much as to be comically overwrought or drained of all value. Bonhoeffer’s theology–his lived theology–is what makes him such a fascinating and important person to this day. Bonhoeffer, in the movie, lands in Germany and is kidnapped by a group of friends in what I can only hope is an attempt to ape the story of Luther being kidnapped and taken in to protect him from enemies. Bonhoeffer then is shown Finkenwalde Seminary, at which, in the movie, the most important thing he does is play a game of soccer and offer forgiveness to Niemoller for being wrong. The movie then immediately has Bonhoeffer sneak into Berlin to see how things are going there. In reality, Bonhoeffer helped plan and fundraise for Finkenwalde, sending letters to people all over Germany and even abroad to raise funds for the illegal seminary at which he developed his theology, wrote quite a bit, and trained a number of Confessing Church pastors. Scenes at this seminary could have shown the trials and tribulations of working through fraught political times while trying to train seminarians in the true Gospel against Nazi propaganda. These points are barely hinted at in the film, as Finkenwalde is but a tiny footnote.

Bonhoeffer’s struggle to decide how exactly to best help in the Confessing Church is occasionally present in the plotline of the film, but for some reason subordinated to the footnoted storyline of Bonhoeffer as assassin-adjacent. In reality, the resisting church was the absolute center of Bonhoeffer’s life for much of his latter years, and would have made a much more interesting and believable story. His concept of religionless Christianity comes up in the film in 1933 at a sermon in Berlin, weirdly, but in actuality that concept was a late development in his theology. I was thankful the film hones in a bit on this concept, but it does very little with it, mostly making it clear that Bonhoeffer saw a distinction between religion and Christ. An attempt was made to tie that to the Nazification of the German church, but it was not clear exactly how that connection was envisioned. I give kudos for at least trying here, but the messaging was so unclear that it is difficult to pinpoint what was going on. Like many other theological ideas presented, the religionless Christianity is hinted at and implied but never really explicated or put into practice.

Bonhoeffer’s ethics are also sacrificed in the movie for the sake of the central Bonhoeffer as vaguely related to an assassination attempt plot. There is no conviction to his positions. He thinks that in America the way they treat black people is clearly wrong, but has to be chastised for thinking nothing is wrong in Germany. He believes killing the Jews is bad (something we don’t historically know how aware he was of it even occurring), but that’s like, a “the bar is on the floor” level of ethics. When he receives pushback on his ethics related to pacifism, he sacrifices it. We don’t get to see any development of his thought in this or any other area. Instead, we are treated to a Bonhoeffer with several absolutes, but one shifting perspective (that on violence in stopping violence) that doesn’t even get more than a quick rebuttal to change his view. When he somehow goes to England to write the Barmen Declaration and publish it in London papers (amusingly read and commented on by nearly everyone in England, apparently), we get little of the meat of his ethics and the whole idea is invented anyway. Bonhoeffer’s ethics are fascinating precisely because they invite deep reflection. His view on pacifism and war and peace has many book length monographs dedicated to it because of its depth, so to see his view dismissed by a brief conversation between himself, Bethge, and Dohnanyi was deeply disappointing and, once again, robbed his life of one of the things that actually makes it worth learning about.

Bonhoeffer’s return to America and realizing he has to “take up a cross” is put in context of his work Discipleship and specifically the quote: “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” While powerfully placed within the context of the movie, it also is robbed of its force when he is then immediately confronted as if he is avoiding that very thing in America, despite his own inner turmoil and demons related to that decision in real life. Bonhoeffer very much did “come and die” for Christ, and even this moment is robbed of its power because one of the greatest quotes in his oeuvre is thrown back in his face almost immediately.

The movie does do a commendable job showing how important the black church was to Bonhoeffer’s time in America, though it does so only by white knighting Bonhoeffer, having him take the spittle and blow for his black friend, Frank Fisher. I didn’t hate the scenes of Bonhoeffer enjoying jazz and gospel music in black communities, something that seems obviously true and also deeply impactful on his life. These scenes actually made him seem more human than reading through his theological works can.

Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran through-and-through, gets a couple chances in the film to hint at or make explicit commitments to sacramental theology. A late scene in the movie has him offering communion to his fellow prisoners, and, for intentional shock/forgiveness value, a Nazi soldier. Bonhoeffer of course had quite a strong view of the church’s authority and certainly would have viewed excommunication as a real option for Nazis, but in context it wasn’t that surprising. He also mentions baptism at least once with the rising waters of a rainy London. Early on, when he’s at Abyssinian Baptist Church, the pastor asks him where he met Jesus (or some similar conversion experience story) and Bonhoeffer comments to the effect of “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran, affirmed infant baptism (even writing at least one sermon for such a ceremony) and baptismal regeneration and so would indeed have seen any kind of conversion moment as a part of one’s faith life as confusing when not tied to that sacrament. The movie did a surprisingly okay job showing this aspect of his theology.

Of course, the question of just how involved Bonhoeffer was in real life in the plot to kill Hitler is itself a question of no small amount of scholarly debate. Obviously there is very little record of what happened, as the conspirators would have intentionally attempted to hide and cover up any such records. Additionally, there is the question of whether Bonhoeffer ever did actually go past his pacifistic beliefs. For my part, I think it’s clear that Bonhoeffer’s ethic aligned with his Lutheranism, and when he wrote that “everyone who acts responsibly must become guilty,” he knew that both it is sinful to act violently against another and sometimes one must act sinfully–becoming guilty for the sake of responsibility to the other. There is a vast chasm between saying “this is the right thing to do, though it is sinful/guilt-inducing” and “this is a good thing to do” related to tyrannicide. The film had no time for such nuance, which is admittedly None of these interesting questions arise in the movie apart from a tiny scene in which Bonhoeffer, who we only find out in this scene is an “avowed pacifist” (apart from a tiny part where he says “I can’t even punch back” to a white racist who hits him in the face with a rifle), is convinced out of being a pacifist by the film’s hero, Dohnanyi.

The clear anti-elitist jab at Union Theological Seminary’s lectures made for a funny moment, but stands against just how clearly Bonhoeffer paid attention and worked hard in those classes. I get that Bonhoeffer was highly critical of the American church, but this isn’t presented apart from this brief look at class at Union. In reality, Bonhoeffer saw white American churches as being caught up in anything but the Gospel, and that was not exclusive to the professors.

Many, many aspects of Bonhoeffer’s life were modified for little apparent reason, and this is reflected time and again. I’ve already said a few things about it above, and while I get things like leaving out his entire time in Barcelona or deciding to have him present at Niemoller’s arrest, I was surprised that Maria von Wedemeyer, his fiancée, doesn’t even appear in the film. The invented scenes of Bonhoeffer’s being kidnapped to go to Finkenwalde and his being swept up as the prayer warrior for an assassination attempt all made it seem as though Bonhoeffer isn’t even the main character in his own life, but rather someone led around by events surrounding him. His friendship with Bethge is barely a plot–he meets him in the incredibly abbreviated Finkenwalde period of the movie, then dismisses his objections about pacifism before Bethge is largely excised from the plot. Bethge served, however, as a sounding board for Bonhoeffer’s ideas and his most intimate and important confidant for the rest of his days. I get taking him out for the sake of time in the movie, but if the film had turned just slightly toward reality, it would have, again, made Bonhoeffer a more interesting and human person.

There are so many other nitpicks that could be made. The end credits talk about Bonhoeffer’s writings filling 34 volumes. Bonhoeffer’s works are 17 volumes in German, and when translated are 17 volumes in English. I actually think they made the mistake of just adding these together as if they comprised his whole works, when they are in fact two copies of the same thing in different languages. Like, that seems to be actually what they did. A search for Bonhoeffer’s works with the number 34 shows up on Logos with 34 volumes–the German and English editions. That’s how thoughtful the research was that went into some aspects of this movie! Bonhoeffer was not arrested because of a plot to kill Hitler but rather because of his involvement in the Confessing Church and his work smuggling Jews to Switzerland. Bonhoeffer absolutely did not write the Barmen Declaration on his own in England. Bonhoeffer’s first sermon did not reference religionless Christianity. The movie “quotes” Bonhoeffer saying the “silence in the face of evil is itself evil, not to speak is to speak, not to act is to act,” a quote that has been proven is not from Bonhoeffer at all. Bonhoeffer didn’t even like strawberries (okay, I made that one up out of spite). These minutiae of incorrect details doesn’t matter that much compared to the overall pointlessness of the movie. I love Bonhoeffer. I wanted this to be a fantastic movie.

There is a vague anti-nationalist message found in the movie, but it would be all too easy for people to tie that only and directly to Nazism rather than realizing that Bonhoeffer’s critiques would absolutely be applied to Christian Nationalism today as found in America.

The worst part of all, though, is that because of the many, many changes to Bonhoeffer’s life, it starts to fall apart as a narrative and the film’s writing isn’t good enough to rescue it. The movie becomes a slog, somehow turning a fascinating life into a boring mess of a film that takes too long to get anywhere. It’s just boring, and that is so sad to me as such a great fan of the man’s life and work.

Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Spy, Assassin ultimately reduces its subject to a shell of the importance of his life. Rather than being a theologian who challenges us today to realize how we have become guilty through our complacency or our willingness to go along with the flow, it mostly writes him as a side character–at best–in an attempt to kill Hitler. The most impactful scenes are near his death, but at that point, everything about the how and why has been reduced down to a plot that it isn’t even clear he was involved in. His ethics, his theology, and his life are largely set to the side in favor of that narrative. And because he’s demonstrably not the main character in that narrative, the film is rather boring. And that’s a crying shame.

Links

Biographies of Dietrich Bonhoeffer: An Ongoing Review and Guide– Want to learn more about Bonhoeffer? You’ve come to the right place. I have a whole bunch of reviews of various biographies of Bonhoeffer, along with recommendations for their target audiences.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Thanks so much for this review! You state, “His view on pacifism and war and peace has many book length monographs dedicated to it because of its depth…” If there was only one I could read, what would you recommend?

Posted by Dave | November 24, 2024, 8:48 AMThanks for stopping by! “Peace and Violence in the Ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer” by Trey Palmasino is a good, short-ish work that shows how Bonhoeffer isn’t to be boxed in to a pacifist or just war type theory. I reviewed the book, highlighting some major themes, here- https://jwwartick.com/2019/08/07/peace-violence-palmisano/

Posted by J.W. Wartick | November 24, 2024, 11:58 AMHello,

I liked a lot of what you said. I heard Komarnicki, the director, speak at Wheaton and got the impression that the is a genuinely very good and likable person and a good artist, but not very knowledgeable, and he needed more than one consultant, especially given said consultant studied Bonhoeffer mostly in connection to Harlem.

On the topic of the England thing, I thing the writers pulled from the Bradford and Bethel confession stories, but I didn’t like that choice very much.

I will add to your list of nitpicking the bit about music: Bonhoeffer would not have hated on classical music (it was a huge part of his upbringing and cultural background!), and the movie does not differentiate between jazz and Black spirituals, meaning the larger reason for Bonhoeffer’s interest in American records (the theological content of the songs) is overlooked in favor of suggesting he just thought jazz was more interesting. And a very pedantic one: when Bonhoeffer and Niemöller preach, the collars on their robes are for Lutheran clergy (tabs apart) when they should be sewn at the top to symbolize the fact that they are part of the Prussian Union (and are united with the Reformed churches, whose collars are sewn together all the way). Of course, I’d have a hard time proving this so I may be wrong but I’m pretty confident in it.

THANK YOU so much for pointing out the thing about the 34 books. It made me roll my eyes. Also, that end credits lists a quote which is generally considered to be a misattributation. All this could have been figured out with light research.

All around a good article. Thanks!

Posted by Megan Norris | August 23, 2025, 2:41 AMThanks for coming by and for your comment. I suspect your insight about the collars is right and that it was intentionally made more recognizable for an American evangelical audience or, perhaps more disturbingly, wasn’t even remotely researched or known about.

The quote is indeed a misattribution.

Good point regarding classical music, Jazz, and Black spirituals, too!

Posted by J.W. Wartick | August 27, 2025, 2:16 PM