J.W. Wartick

Book Review: “The New Testament in Color: A Multiethnic Bible Commentary”

The New Testament in Color: A Multiethnic Bible Commentary is an attempt to bring together people from many different backgrounds to offer commentary on the New Testament.

After an introduction, readers get essays on African American, Asian American, Hispanic, Turtle Island, and Majority-Culture biblical interpretation. Then, the book launches into individual authors offering commentaries on each book of the New Testament. Interspersed are a few selected essays on gender in the New Testament, resources for the mental health of the oppressed in the NT, multilingualism, and immigrants in the Kingdom of God.

The commentaries on individual books of the Bible are usually close to chapter-by-chapter, with authors seemingly getting a good amount of leeway with how focused they ought to be verse-by-verse. The format lends itself to deeper discussion of individual topics each author wants to write about, but makes it a bit less useful if one is looking specifically for a verse-by-verse commentary.

The commentary itself is consistently excellent and thought-provoking. I recall especially one moment while reading the commentary on Luke in which the author, Diane G. Chen, whose parents are Chinese, reflected on the passage about treasures in heaven (Luke 12:13-34). Chen wrote about her parents teaching her to save, live within her means, and how to balance that with the concern of a safety net turning into worldliness and power. Time and again insights are offered into the Bible that spring from the cultural traditions of the authors included. The contributors hail from all over the world, with many different background represented.

There are a number of ways a commentary like this could have been formatted. I think about the series of Reformation Commentaries in which individual verses or sections are given comments from multiple different Reformers. I’m glad the editors chose a mode which allowed the authors to give running commentary on entire books of the Bible as it allows readers more insight into the thoughts and breadth of ideas of each individual author.

The New Testament in Color serves as a fantastic resource and, frankly, a fascinating read. I highly recommend it for those interested in diving deeply into what the Bible is telling us today.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

YHWH and his Asherah? – Biblical Archaeology and Avoiding Dogmatic Conclusions

It is incredibly easy to fall victim to the idea that by reading just a few things on a topic by experts, you are suddenly an expert on the topic–or at least know enough to expertly comment upon it. There have even been studies on this and the eventual name given has been the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Biblical archaeology is absolutely one of those areas in which it is simple to get caught up in that problematical space between expert and one with no knowledge. In part, that’s because archaeology and historical study are such impossibly complex topics that even getting to the details of methodology can be daunting. Reading one take and moving on as if we have the facts is far easier.

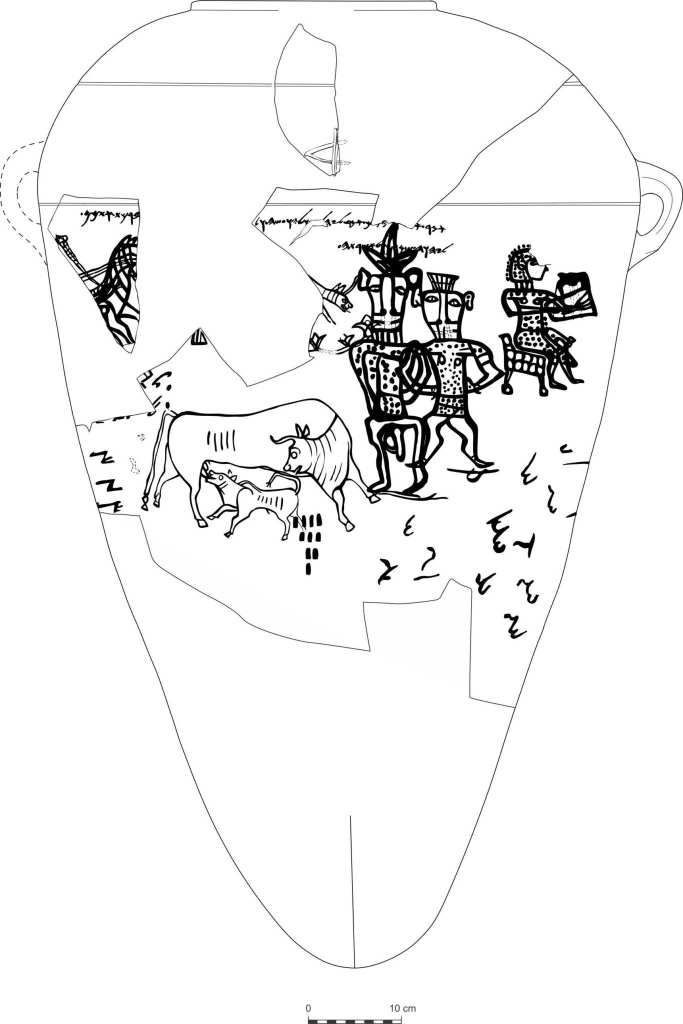

This was recently made clear to me personally when I encountered Theodore J. Lewis’s discussion of inscriptions found at Kuntillet Arjud in his book The Origin and Character of God. There, he notes that some scholars have seen “the female seated lyre player…” as a depiction of Asherah, accompanied by the text “Yahweh of Samaria and his asherah” ((a), 125). However, unlike Dever (discussed below) and others, Lewis notes that this is “inadvisable” because “There is no association of Asherah with music, nor would one expect to find the great mother goddess off center…” and the inscription and imagery likely “come from two separate times.” Additionally, this concept doesn’t account for there being three figures (ibid). Moreover, throughout this section, Lewis notes how difficult it is to parse the difference between asherah as a cultic symbol–an asherah pole or tree that was used in religious practices in Canaan–and citations related to Asherah the goddess, due to them being the same word. Indeed, it is difficult to even fully know whether such a distinction itself is valid.

By contrast, William G. Dever in his Beyond the Texts, cites the same find as depicting “two Bes figures and a half-nude female playing a lyre” ((c), 499). In a note, he argues that the depiction is a reference to Asherah as the goddess, not asherah as a cultic symbol, arguing that despite the missing possessive suffix, it is “graffiti” and so doesn’t need to apply all grammatical rules (ibid, n114, 543). He also argues that reading asherah as a cultic symbol in this inscription (and likely elsewhere) is reflective of “theological presuppositions” rather than the data (ibid).

This may seem a rather obscure fight to be having, but it is not. It would be indicative of at least some aspects of Israelite religion in the region if they saw Asherah as a divine consort of YHWH, something Dever argues elsewhere. However, Lewis does not see this same depiction as evidence of Asherah as YHWH’s consort, and Dever does not here suggest any reason for the third depicted figure (he apparently takes the figure next to the supposed YHWH figure as being Asherah, along with a third seated musician as a different figure).

Not only that, but Dever and Lewis’s approaches are markedly different related to how to treat archaeological and textual data more generally. Dever’s work’s name, Beyond the Texts, hints at his general approach, which he makes explicit therein–elevating archaeological data as perhaps just as significant as textual data. Lewis, however, notes repeatedly the difficulties inherent in using archaeological data to make points beyond the texts. One way this contrast can be seen is Lewis’s suggestion–backed by some scholars cited–that figurines found at archaeological sites should be seen as mortal–not divine–unless the figure being mortal is ruled out by some means (eg. a certain headdress known to be associated with a specific deity, see Lewis, 121ff).

I am by no means an expert in ANE material, archaeology, or historiography. I have studied each, including on master’s level courses, but only obliquely. This was another example that showed me how easy it is to be caught up in expert opinions. I read Dever first and found it utterly convincing, seeing the likelihood that in at least some times and places in ancient Israel, YHWH was likely depicted with a wife. Lewis, a work I’m still in progress of reading, seems to temper that expectation and conclusion somewhat. How do we know which to trust?

I think it is important to realize that as a non-expert, we don’t really need to have a firm opinion on this, in part because we don’t have the knowledge base to even do so. But it is important to be aware of our limitations. Additionally, it is important to realize additional limitations that both Lewis and Dever point out with both archaeology and texts. Archaeology is necessarily limited to what is found by archaeologists, which various studies suggest is an astronomically tiny percentage of all the material that might exist to be excavated. Additionally, the material that survives–even that not yet excavated, is only a tiny percentage of all the material of a culture. Not only were things reused and repurposed, but they were also destroyed, often intentionally. Thus, we are seeing only tiny parts of the true material culture of the ancient past. This applies to texts as well. There are untold numbers of texts forever lost to time that could give any number of clarification on so many fascinating topics. We should be thankful for what we can find, but realize that caution regarding conclusions is deeply important.

Regarding YHWH and Asherah–I don’t know. I think that some of this relies upon religious presuppositions, and I’m including Dever in on that. But I also think that there seems to be enough scattered evidence to suggest that there is some connection between the two. I’ll be interested to read the rest of Lewis’s book and see what he argues with the rest of the material about Asherah and asherah poles. For my readers here, I hope this can serve as a cautionary tale to be aware of how little we know, especially as non-experts.

That said, two things that are extremely clear are that: 1. the Biblical material itself shows evidence of religious development in Israel, and this can be extracted and shown alongside archaeological evidence; ancient Israel did not have a monolithic, exclusively monotheistic religion, though it seems the elites may have developed that and enforced it eventually; 2. there is so much more to the religion(s) of ancient Israel and the region that we have to learn, and certainly far more than the simplistic stories that we tend to learn in church. That doesn’t mean those simplistic stories are to be utterly rejected or seen as misleading or intentionally untrue; merely that there is, as almost always, more complexity than what we learned on a surface level.

Sources

(a) Lewis, Theodore J., The Origin and Character of God: Ancient Israelite Religion through the Lens of Divinity (New York, 2020: Oxford).

(b) Choi, G. (2016). “The Samarian Syncretic Yahwism and the Religious Center of Kuntillet ʿAjrud”. In Ganor, Saar; Kreimerman, Igor; Streit, Katharina; Mumcuoglu, Madeleine (eds.). From Shaʿar Hagolan to Shaaraim: Essays in Honor of Prof. Yosef Garfinkel. Israel Exploration Society.

Dever, William G., Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah (Atlanta, 2017: SBL).

SDG.

Learning about Reformation History: “Melanchthon: The Quiet Reformer” by Clyde L. Manschreck

I have long wondered about Philip Melanchthon. He seemed to get vilified in a lot of Lutheran circles I ran in, but he also was clearly at the forefront of Lutheran theology at the time of its formation. Luther rarely seemed to have said anything negative about Melanchthon, but the charge was that he turned away from Lutheranism later in his life and compromised. Enter Clyde L. Manschreck’s excellent biography, Melanchthon: The Quiet Reformer. Manschreck presents a fascinating, balanced perspective on Melanchthon, one of the most intriguing of Reformation persons.

Manschreck starts off, appropriately enough, with looking at how Melanchthon has been treated historically. Surprisingly few biographies exist of the Reformer, especially compared to other luminaries of the period who had less of an impact. After his death, there was criticism from three fronts: he was too Lutheran for Catholics, too Calvinist for Lutherans, and too Catholic for Calvinists. That’s oversimplifying it a bit, but it becomes clear that his legacy was marred by attacks from all sides. So who was the man, and what did he really believe–and was he an infamous compromiser?

Manschreck moves very swiftly past Melanchthon’s early life, almost immediately settling into the time that brought him to Wittenberg. But as Manschreck paints the picture of Melanchthon’s time there, first as an extraordinary lecturer with phenomenal skill and later as a Reformer, we also get deep insight into his character and beliefs. Melanchthon, like many early Lutherans (and a huge amount of the surrounding population) believed in astrology. It’s a strange thing when you look back on it, but it was conceived as a kind of science. Melanchthon was a firm believer, even lamenting the sign a child-in-law was born under when he came to dislike them. Melanchthon also was a champion for public schools, creating the first publicly funded schools across Germany, and advocated for (and got) living wages for teachers. His reasoning was that if a teacher had to work yet another job to just be able to eat or live, the wouldn’t be able to focus on bettering their mind and, in turn, their students’ minds.

Melanchthon and Luther hit it off almost immediately, and Melanchthon joining the Reformation was an organic thing, rather than something one can just point to a single moment as the moment of changing of heart. He clearly believed in the arguments of justification, and ultimately became one of the primary (or the primary) authors of much of the Lutheran Confessions. Setting the writing of these alongside the circumstances in which they occurred makes them more understandable. The Augsburg Confession being prepared to try to, in part, make it clear that their movement wasn’t heretical and could be defended on Scriptural grounds is a fascinating story. Additional clarification due to attempts to unite with other Reformers–attempts that ultimately failed with Zwingli and Calvin–is also set in its historical perspective. The writing of the Confessions should not be separated in understanding from their historical circumstances.

Fascinating historical details about Melanchthon’s life can be found in abundance. Did you know that he had no small amount of correspondence with Henry VIII? The latter desired Melanchthon’s comments on his marriage, hoping the Reformer might be open to giving him an out. Even when Melanchthon failed to deliver for Henry VIII, the King realized the political expediency of an alliance and, perhaps, even was swayed ever so slightly towards some Protestant points. Manschreck makes it clear Henry VIII’s interest was almost certainly political–how to get out of an undesired marriage in a desirable way.

Ultimately, Manschreck paints Melanchthon as a man of convictions who was willing to change his beliefs as he learned more. One of the most obvious examples was Melanchthon’s shift towards a kind of spiritualized view of real presence regarding the Lord’s Supper. What’s interesting with this is that Manschreck is able to document that Luther was aware of this shift and yet explicitly did not condemn it, despite multiple means and opportunities to do so. Was it out of respect for Melanchthon? Or was it a recognition that Melanchthon’s position was somewhere within the Lutheran fold (a fold that is anachronistic to apply to the situation anyway)? I don’t know, but it is worth reading the whole account, including Luther’s non-condemnation. Perhaps Melanchthon could be somewhat welcomed back into Lutheran teaching on some level? Again, I know not. But what’s clear is that Melanchthon sought to go back to the source (the ad fontes of the Reformation and Renaissance) and to understand Scripture’s teaching without trying to invent new doctrines.

Melanchthon: The Quiet Reformer is a superb biography that is well worth the read by any wishing to learn more about one of the most important figures of the early Reformation. I found it informative, balanced, and of interest to even broader world events.

Links

Reformation Theology– Check out all my posts on various topics related to the Reformation (scroll down for more).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Spy, Assassin” or, how to turn a martyred theologian’s life into a pointless, directionless slog

Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Spy, Assassin is, ostensibly, a film about the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German pastor and theologian who was murdered by the Nazis. Bonhoeffer’s works have been incredibly formative in my own life and faith formation. I’ve read and reread his works for over a decade, and I was incredibly excited to see an attempt to make his life into a blockbuster film. That being said, the movie was a great disappointment. It is important to discuss why and how it was disappointing, though, because I think that matters.

First, I think biopics almost always have to fudge on details and stories. That’s fine. Often, for the sake of time, films have to combine life events together, omit details, and tell aspects of one’s life in a more interesting (read: usually action packed) way in order to keep the movie flowing. I am not planning to critique the movie (much) for this apart from where it is necessary.

The most important critique I want to offer of the film, though, is that it turns Bonhoeffer’s life into something that is at its core, almost entirely pointless. In the movie, Bonhoeffer is arrested for attempting to kill Hitler (not historically accurate) and at his execution, that’s the reason (along with money laundering) that he is executed. But in the movie, Bonhoeffer’s alleged involvement in the plot to assassinate Hitler amounts to virtually nothing. This is what is actually depicted in the movie: 1. Bonhoeffer agrees with his brother-in-law Hans Dohnanyi to join violent resistance against Hitler, over the protestations of his friend Eberhard Bethge that he should remain committed to pacifism; 2. he prays with a guy who’s going to wear a bomb to try to kill Hitler; 3. he is asked by Dohnanyi to try to get a bomb from Churchill and fails. What exactly was this supposedly heroic act that Bonhoeffer did, according to the movie’s own narrative arc that makes him so incredibly amazing? What makes him into this wonderful martyr or hero of the resistance? Nothing, according to the movie. He barely had even tangential awareness of what was happening in the attempt to kill Hitler, even according to the film. But because the film makes that the central aspect of Bonhoeffer’s life, the culmination of his theological work, it drains Bonhoeffer’s life and theological work of its actual power. And because the assassination attempt was manifestly not the central aspect of Bonhoeffer’s actual life, the film struggles to shoehorn it in and then fails to even make that interesting.

The film thus turns Bonhoeffer’s life into a pointless footnote. It is Dohnanyi who is the real hero of the Bonhoeffer movie, a man who infiltrated the Abwehr, worked to save Jews, acquired the bomb, and planned the assassination attempt. Bonhoeffer did what? He prayed for the success of the mission? How does that make him into an interesting character?

The real parts of Bonhoeffer’s life that make his story so vital or interesting are, somewhat ironically, either glossed over or modified so much as to be comically overwrought or drained of all value. Bonhoeffer’s theology–his lived theology–is what makes him such a fascinating and important person to this day. Bonhoeffer, in the movie, lands in Germany and is kidnapped by a group of friends in what I can only hope is an attempt to ape the story of Luther being kidnapped and taken in to protect him from enemies. Bonhoeffer then is shown Finkenwalde Seminary, at which, in the movie, the most important thing he does is play a game of soccer and offer forgiveness to Niemoller for being wrong. The movie then immediately has Bonhoeffer sneak into Berlin to see how things are going there. In reality, Bonhoeffer helped plan and fundraise for Finkenwalde, sending letters to people all over Germany and even abroad to raise funds for the illegal seminary at which he developed his theology, wrote quite a bit, and trained a number of Confessing Church pastors. Scenes at this seminary could have shown the trials and tribulations of working through fraught political times while trying to train seminarians in the true Gospel against Nazi propaganda. These points are barely hinted at in the film, as Finkenwalde is but a tiny footnote.

Bonhoeffer’s struggle to decide how exactly to best help in the Confessing Church is occasionally present in the plotline of the film, but for some reason subordinated to the footnoted storyline of Bonhoeffer as assassin-adjacent. In reality, the resisting church was the absolute center of Bonhoeffer’s life for much of his latter years, and would have made a much more interesting and believable story. His concept of religionless Christianity comes up in the film in 1933 at a sermon in Berlin, weirdly, but in actuality that concept was a late development in his theology. I was thankful the film hones in a bit on this concept, but it does very little with it, mostly making it clear that Bonhoeffer saw a distinction between religion and Christ. An attempt was made to tie that to the Nazification of the German church, but it was not clear exactly how that connection was envisioned. I give kudos for at least trying here, but the messaging was so unclear that it is difficult to pinpoint what was going on. Like many other theological ideas presented, the religionless Christianity is hinted at and implied but never really explicated or put into practice.

Bonhoeffer’s ethics are also sacrificed in the movie for the sake of the central Bonhoeffer as vaguely related to an assassination attempt plot. There is no conviction to his positions. He thinks that in America the way they treat black people is clearly wrong, but has to be chastised for thinking nothing is wrong in Germany. He believes killing the Jews is bad (something we don’t historically know how aware he was of it even occurring), but that’s like, a “the bar is on the floor” level of ethics. When he receives pushback on his ethics related to pacifism, he sacrifices it. We don’t get to see any development of his thought in this or any other area. Instead, we are treated to a Bonhoeffer with several absolutes, but one shifting perspective (that on violence in stopping violence) that doesn’t even get more than a quick rebuttal to change his view. When he somehow goes to England to write the Barmen Declaration and publish it in London papers (amusingly read and commented on by nearly everyone in England, apparently), we get little of the meat of his ethics and the whole idea is invented anyway. Bonhoeffer’s ethics are fascinating precisely because they invite deep reflection. His view on pacifism and war and peace has many book length monographs dedicated to it because of its depth, so to see his view dismissed by a brief conversation between himself, Bethge, and Dohnanyi was deeply disappointing and, once again, robbed his life of one of the things that actually makes it worth learning about.

Bonhoeffer’s return to America and realizing he has to “take up a cross” is put in context of his work Discipleship and specifically the quote: “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” While powerfully placed within the context of the movie, it also is robbed of its force when he is then immediately confronted as if he is avoiding that very thing in America, despite his own inner turmoil and demons related to that decision in real life. Bonhoeffer very much did “come and die” for Christ, and even this moment is robbed of its power because one of the greatest quotes in his oeuvre is thrown back in his face almost immediately.

The movie does do a commendable job showing how important the black church was to Bonhoeffer’s time in America, though it does so only by white knighting Bonhoeffer, having him take the spittle and blow for his black friend, Frank Fisher. I didn’t hate the scenes of Bonhoeffer enjoying jazz and gospel music in black communities, something that seems obviously true and also deeply impactful on his life. These scenes actually made him seem more human than reading through his theological works can.

Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran through-and-through, gets a couple chances in the film to hint at or make explicit commitments to sacramental theology. A late scene in the movie has him offering communion to his fellow prisoners, and, for intentional shock/forgiveness value, a Nazi soldier. Bonhoeffer of course had quite a strong view of the church’s authority and certainly would have viewed excommunication as a real option for Nazis, but in context it wasn’t that surprising. He also mentions baptism at least once with the rising waters of a rainy London. Early on, when he’s at Abyssinian Baptist Church, the pastor asks him where he met Jesus (or some similar conversion experience story) and Bonhoeffer comments to the effect of “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran, affirmed infant baptism (even writing at least one sermon for such a ceremony) and baptismal regeneration and so would indeed have seen any kind of conversion moment as a part of one’s faith life as confusing when not tied to that sacrament. The movie did a surprisingly okay job showing this aspect of his theology.

Of course, the question of just how involved Bonhoeffer was in real life in the plot to kill Hitler is itself a question of no small amount of scholarly debate. Obviously there is very little record of what happened, as the conspirators would have intentionally attempted to hide and cover up any such records. Additionally, there is the question of whether Bonhoeffer ever did actually go past his pacifistic beliefs. For my part, I think it’s clear that Bonhoeffer’s ethic aligned with his Lutheranism, and when he wrote that “everyone who acts responsibly must become guilty,” he knew that both it is sinful to act violently against another and sometimes one must act sinfully–becoming guilty for the sake of responsibility to the other. There is a vast chasm between saying “this is the right thing to do, though it is sinful/guilt-inducing” and “this is a good thing to do” related to tyrannicide. The film had no time for such nuance, which is admittedly None of these interesting questions arise in the movie apart from a tiny scene in which Bonhoeffer, who we only find out in this scene is an “avowed pacifist” (apart from a tiny part where he says “I can’t even punch back” to a white racist who hits him in the face with a rifle), is convinced out of being a pacifist by the film’s hero, Dohnanyi.

The clear anti-elitist jab at Union Theological Seminary’s lectures made for a funny moment, but stands against just how clearly Bonhoeffer paid attention and worked hard in those classes. I get that Bonhoeffer was highly critical of the American church, but this isn’t presented apart from this brief look at class at Union. In reality, Bonhoeffer saw white American churches as being caught up in anything but the Gospel, and that was not exclusive to the professors.

Many, many aspects of Bonhoeffer’s life were modified for little apparent reason, and this is reflected time and again. I’ve already said a few things about it above, and while I get things like leaving out his entire time in Barcelona or deciding to have him present at Niemoller’s arrest, I was surprised that Maria von Wedemeyer, his fiancée, doesn’t even appear in the film. The invented scenes of Bonhoeffer’s being kidnapped to go to Finkenwalde and his being swept up as the prayer warrior for an assassination attempt all made it seem as though Bonhoeffer isn’t even the main character in his own life, but rather someone led around by events surrounding him. His friendship with Bethge is barely a plot–he meets him in the incredibly abbreviated Finkenwalde period of the movie, then dismisses his objections about pacifism before Bethge is largely excised from the plot. Bethge served, however, as a sounding board for Bonhoeffer’s ideas and his most intimate and important confidant for the rest of his days. I get taking him out for the sake of time in the movie, but if the film had turned just slightly toward reality, it would have, again, made Bonhoeffer a more interesting and human person.

There are so many other nitpicks that could be made. The end credits talk about Bonhoeffer’s writings filling 34 volumes. Bonhoeffer’s works are 17 volumes in German, and when translated are 17 volumes in English. I actually think they made the mistake of just adding these together as if they comprised his whole works, when they are in fact two copies of the same thing in different languages. Like, that seems to be actually what they did. A search for Bonhoeffer’s works with the number 34 shows up on Logos with 34 volumes–the German and English editions. That’s how thoughtful the research was that went into some aspects of this movie! Bonhoeffer was not arrested because of a plot to kill Hitler but rather because of his involvement in the Confessing Church and his work smuggling Jews to Switzerland. Bonhoeffer absolutely did not write the Barmen Declaration on his own in England. Bonhoeffer’s first sermon did not reference religionless Christianity. The movie “quotes” Bonhoeffer saying the “silence in the face of evil is itself evil, not to speak is to speak, not to act is to act,” a quote that has been proven is not from Bonhoeffer at all. Bonhoeffer didn’t even like strawberries (okay, I made that one up out of spite). These minutiae of incorrect details doesn’t matter that much compared to the overall pointlessness of the movie. I love Bonhoeffer. I wanted this to be a fantastic movie.

There is a vague anti-nationalist message found in the movie, but it would be all too easy for people to tie that only and directly to Nazism rather than realizing that Bonhoeffer’s critiques would absolutely be applied to Christian Nationalism today as found in America.

The worst part of all, though, is that because of the many, many changes to Bonhoeffer’s life, it starts to fall apart as a narrative and the film’s writing isn’t good enough to rescue it. The movie becomes a slog, somehow turning a fascinating life into a boring mess of a film that takes too long to get anywhere. It’s just boring, and that is so sad to me as such a great fan of the man’s life and work.

Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Spy, Assassin ultimately reduces its subject to a shell of the importance of his life. Rather than being a theologian who challenges us today to realize how we have become guilty through our complacency or our willingness to go along with the flow, it mostly writes him as a side character–at best–in an attempt to kill Hitler. The most impactful scenes are near his death, but at that point, everything about the how and why has been reduced down to a plot that it isn’t even clear he was involved in. His ethics, his theology, and his life are largely set to the side in favor of that narrative. And because he’s demonstrably not the main character in that narrative, the film is rather boring. And that’s a crying shame.

Links

Biographies of Dietrich Bonhoeffer: An Ongoing Review and Guide– Want to learn more about Bonhoeffer? You’ve come to the right place. I have a whole bunch of reviews of various biographies of Bonhoeffer, along with recommendations for their target audiences.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Reading the Bible Against Ourselves- Bonhoeffer’s Ethical Insight on Scripture

Christians today, especially in the United States, seem to be completely incapable of engaging in one of the most important and powerful ways of reading Scripture. Dietrich Bonhoeffer saw a similar lack in his own time, and at an ecumenical International Youth Conference in Gland, Switzerland, he implored the youths there to engage in this important practice. What is it? It is the practice of reading the Bible as though its prophecies or ethical were written against us. As Bonhoeffer put it:

“[H]as it not become terribly clear, again and again, in all that we have discussed with one another here, that we are no longer obedient to the Bible? We prefer our own thoughts to those of the Bible. We no longer read the Bible seriously. We read it no longer against ourselves but only for ourselves…” (DBWE 11:377-378).

Elsewhere, Bonhoeffer writes of some of the discomfort of being part of the classes in Germany that don’t have to worry about money, and this is the kind of thing I think that reading the Bible against ourselves can forcefully mean. The point was brought home to me recently when I was engaging with a number of other Christians on social media about wealth. Many of them were defending not just rival political theories that favored the wealthy, but actually defending the wealthy and themselves as people who have wealth. The art of reading the Bible against ourselves is completely lost in such circles.

It should not be possible to read the Bible’s words on how difficult it is for the rich to enter the Kingdom of Heaven; or the obligation to feed, clothe, and house others; or to read James’s words for the rich and fair wages; or to read 1 Timothy’s words about love of money and not feel discomfort in the United States. As a country we are filled to the brim with wealth, even as that wealth is horded by the upper echelons of society. But individually, even many of our poor are wealthy in terms of the world. So many don’t have to worry about where they’ll find their next meal, or whether they’ll have a shirt on their back, or anything of the sort. Yet we–even I–are the people who are called to sell everything we have and give it to the poor, and do not do so. And then to turn around and defend not just policies that favor the rich over the poor, but to argue that that is what Christians ought to do–it’s alarming at best.

We no longer read the Bible seriously. We read it only for ourselves. If it’s inconvenient, we re-interpret it, using our privileged position to see it as something that doesn’t really demand that we sell what we have to feed the hungry. We hide behind political systems or economic systems and ignore the horrors that those very systems bring, whether through the exploitation of child labor or the destruction of God’s green Earth.

We absolutely must learn again to read the Bible against ourselves so that we may walk more humbly and seek to correct wrongs, even as we realize we cannot correct every wrong and that only God can bring complete healing of the world and its ills.

Source

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, Volume 11: Ecumenical, Academic, And Pastoral Work: 1931-1932 (Fortress Press).

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Migrations of the Holy: God, State, and the Political Meaning of the Church” by William T. Cavanaugh

It would be difficult for me to understate how much reading William T. Cavanaugh’s book, The Myth of Religious Violence, changed my perspective and set me on paths exploring my faith and its relations with the world. Now, re-reading Migrations of the Holy: God, State, and the Political Meaning of the Church, once again has my head spinning and my thoughts going. Cavanaugh challenges readers to see that “religion” has never left in the west, but our religious fervor has instead been migrated to a new object of worship: the nation state.

Cavanaugh’s work here was written before the recent rise of Christian Nationalism, and it feels utterly prescient in so many ways. But beyond feeling predictive, it also provides warnings and evaluative principles to see how Christians–and other religious persons–in the so-called “West” have preserved deeply religious, deeply committed lifestyles but have simply moved their loyalty from radical loyalty to God-and-other to radical loyalty to the nation state. This can be seen in any number of ways, whether through the veneration of the flag of one’s favored nation state, complete with elaborate ceremonies for the exactly right and proper way to fold the flag to the way people are honored for their “service” to the nation state in the military and other endeavors.

The language used by Cavanaugh helps frame the narrative. He also uses quotes and interlocutors effectively. One example of the latter is the framing of the first chapter, entitled “Killing for the Telephone Company.” The comparison to killing in the name of the nation state and killing for the telephone company creates a radical juxtaposition that shows how absurd it seems to do the former, just as it is the case in the latter.

Cavanaugh’s argument builds on itself. An early assertion that “the state is not a product of society, but creates society” (18) is backed by a number of quotes and commentators from Hobbes to modern political theorists. The migration of the holy from so-called “religious” realms to the supposedly secular nation state is traced along a number of lines. One example draws all the way back on Augustine, who argued that coercive government is a [necessary-ish in his argument] result of the Fall (61). The movement of holy from church to state also creates a crisis for the church, which could lead to a kind of separation from the state even as the state continues to assert sovereignty over all aspects of life.

One later chapter offers a “Christian theological critique of American Exceptionalism” (88ff). Here, we find Cavanaugh fully in his element: “[W]hen a direct, unmediated relationship is posited between America and a transcendent reality, either God or freedom, there is a danger that the state will be divinized” (89). The conceptual nature of “freedom” as highest ideal and seeing America along theological notions of the doctrine of election create a dangerous situation in which the nation state is the object of veneration even as it functions as the arbiter of truth through violence projected internationally. “We [Americans] know what is good for everyone and we have the power to enforce that vision anywhere in the world” (95). This was seen in the time of the publishing of the book (2011) in the continuation of the occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan and can be seen into today with American power being projected internationally for the sake of tenuous and rarely-defined ideals of freedom.

Part of the migration of holy from church to state is the same myth of religious violence Cavanaugh wrote of in his book of that title. By democratizing violence; by moving it directly and exclusively into the sphere of the nation state, we have created dichotomies that are enforced systematically through “us in the West and them, the less enlightened peoples of the world” (111). Violent conflict is reframed in a narrative of cosmic rightness and wrongness, again showing the concept of holiness and judgment as the purview of the nation state (ibid and following). One example of this is “The recent debate over the use and justification of torture by the U.S. government… On the one hand, we claim that we do not torture; on the other hand, we imply that we must” (112). Violence is only accepted in the hands of the nation state and for the sake of whatever ends that nation state has framed as righteous: freedom and liberty, for example.

Cavanaugh puts the reality of holiness as nation state even more starkly when it comes to the use of violence: “It is clear that, among those who identify themselves as Christians in the United States and other countries, there are very few who would be willing to kill in the name of the Christian God, whereas the willingness, under certain circumstances, to kill and die for the nation in war is generally taken for granted” (119). This, of course, is not intended to suggest that violence should be done in the name of the Christian God. The point is, instead, to show that violence itself as showing dedication is wholly in the realm of the sovereign state now. Cavanaugh reinforces this in writing on the Eucharist as God sacrificing God’s self for us, an entirely foreign concept to that of loyalty to the nation state (121-122). From here, Cavanaugh moves into a kind of political theory for the church, among other things.

Honestly, reviewing a book like this almost feels wrong to me. Both of these works by Cavanaugh have had such a massive impact on how I think about things that I worry I cannot convey that adequately in a simple book review. How many superlatives are too many? How much praise is too much? I don’t know. But suffice to say that I believe Migrations of the Holy is a paradigm-shifting book. I hope you’ll read it.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Thriving with Stone Age Minds: Evolutionary Psychology, Christian Faith, and the Quest for Human Flourishing” by Justin L. Barrett with Pamela Ebstyne King

Thriving with Stone Age Minds is a fascinating journey into looking at a combination of evolutionary psychology and Christian faith.

First, this book is not located in the space of debating Christianity and evolution. It simply assumes mainstream science is correct and that Christianity remains viable given that. Frankly, that makes the book more useful, in my opinion, than it would have been if it spent pages trying to justify those premises. There is an introductory chapter that goes over some basic assumptions and background knowledge necessary for at least diving in to the later chapters.

Next, there’s the question of what it means to “thrive.” The definition is more complex than a reader may think, especially when one is attempting to balance both evolutionary and Christian theological assumptions. Thriving in this space means there can be gaps in understanding, and that finding a niche means more than successful procreation and passing on of genetic code. Humans also tend to expand into whatever space they find and modify nature to suit their needs; this creates a kind of nature-niche gap that is crossed repeatedly by humans, but might not also yield thriving.

The authors go over various features of human anatomy and what those features might suggest about human nature. For example, humans have large white sclerae in our eyes that allows others to see where we’re directing our attention. The nature-niche gap also refers to how quickly humans are moving various aspects of our lives ahead of nature. For example, our nutrition is linked to our evolutionary past, when finding sugar and fat-rich foods would have been important sources of large nutritional importance; but they are hyper-abundant now and our bodies and minds haven’t been trained or evolved to combat this massive availability.

Some focus of the book is on contrasting the pace of revolutionary change and adaptation and the extremely rapid advancement of technology and–tying into the above–diet and availability of food. Evolutionary psychology can help us understand some of the gaps in understanding and the necessity of learning more about how technology is changing our minds and bodies. Each chapter has a number of ways to focus on the concept of thriving and tying it into both Christian theology and evolutionary biology.

Thriving with Stone Age Minds is a highly recommended read. It rewards careful reading and spurs quite a bit of thought.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Bonhoeffer and the Challenge of Ecumenism

Ecumenism–the work of bringing unity to worldwide Christianity–is a constantly challenging work throughout the history of the church. Dietrich Bonhoeffer was deeply involved in ecumenical movements in his own time. One fascinating aspect of this is that while Bonhoeffer worked for ecumenism, he also was quite clear that the German Christian Church, which had been taken over by the Nazis, was no longer a Christian church and could not be designated as such. In calling out the German Christians, Bonhoeffer presented one of the great challenges of ecumenism: how to define “in” or “out” when it comes to Christianity.

The obvious and immediate objection here, of course, is that the German Christian church was actually being run by Nazis. Historical retrospect with 20/20 vision allows us to say that clearly, such a church had indeed lost the Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ. However, at the time, such historical vision did not exist. Instead, we can see some of the challenges inherent in ecumenical work in a fascinating exchange Bonhoeffer had with Canon Leonard Hodgson[1]. The exchange can be found in Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Works in English, Volume 14: Theological Education at Finkenwalede: 1935-1937. Bonhoeffer was invited by Hodgson in 1935 to come to the World Council of Churches as a visitor to the meeting of the Continuation Committee. Bonhoeffer declined, writing, “I should very much like to attend the meeting. But there is first of all the question if representativies of the Reichskirchenregierung [Reich Church Government (of the Nazi-sanctioned German Christian Church)] will be present, which would make it impossible for me to come” (DBWE 14, 68). Hodgson wrote back, imploring Bonhoeffer to attend. After noting that representatives of the German Christian church would be attending, Hodgson wrote, “I think you will understand our position when I say that we cannot, as a Movement [the World Council of Churches and the ecumenical movement], exclude the representatives of any Church which ‘accepts our Lord Jesus Christ as God and Saviour.’ Right from the start, there has been a general invitation to all such churches, and we cannot arrogate to ourselves the right to discriminate between them…” (Ibid, 69).

Defining a Christian church as one which “accepts our Lord Jesus Christ as God and Savior” seems like a reasonable step, especially within an ecumenical movement. But is it enough? That must always be the lingering question, and I’m not sure it is one I can answer. Bonhoeffer, however, answered Hodgson directly. After thanking Hodgson for the repeated invitation to attend, he wrote, “Can there be anything finer and more promising to a Christian pastor and teacher than to co-operate in the preparation for a great oecumenical[2] synod…?” But, then he went on to note that the Confessional Church in Germany did not believe the German Christian church did in fact believe that Jesus Christ is God and Savior. Wrote Bonhoeffer, “There may be single representatives…. who propound a theology which is to be called a Christian theology… But the teaching as well as the action of the responsible leaders of the Reich Church has clearly proved that this church does no longer serve Christ but that it serves the Antichrist… The Reich Church…. continues to betray the one Lord Jesus Christ, for no man can serve two masters…” (DBWE 14, 71-72).

It is hardly possible to issue a more direct and explicit statement than Bonhoeffer did regarding the status of the German Christian Church. He simply asserted: it serves the Antichrist. He went on to note the Confessional Church’s condemnation of the German Christian Church and some specific points thereof.

Hodgson, however, persisted. And his letter is one that highlights so many difficulties with ecumenism. Before diving in further, it is worth noting I am in favor of ecumenism, generally. Just as Bonhoeffer quoted Jesus’s words in John 17:21 to note that Christ wishes all of His followers to be one; so we should also wish for that and work towards it. However, where do lines get drawn, if at all? And surely, a church being taken over by a Nazi state is enough to draw the line? But even so, the historical difficulty of doing so, reflected in the words of Hodgson, should give us some fuel for thought in our own time.

Hodgson countered first by noting the 400+ years of the Ecumenical Movement, always seeking to unite the churches that had been separated. The Movement itself, Hodgson argued, must never act in behalf of individual church bodies; instead it worked as a kind of outside guiding body to bring those individual churches together. Hodgson highlighted that acceptance of Jesus Christ as God and Savior is the “one and only qualification” for a Christian church and that “the Movement has never taken upon itself to decide which churches conform to this definition and which do not” (DBWE 14, 78). He raised a neutral example of a Czechoslovakian National Church and internal debates with others over whether that church was Trinitarian or Unitarian. Turning to the Confessional and Reich church in Germany, Hodgson noted that the former appeared to have stated that the latter no longer accepted the sole criterion required by ecumenism. However, he also argued that the Reich church did not seem to see itself as outside the bounds of that confession; and who is the Ecumenical Movement to arbitrate such disagreements (Ibid)? After all, if they took up the question of the Confessional vs. Reich Church, where does it end? Could not various American churches raise charges against each other that, even while denying such a denial existed, one church does not really believe in Jesus Christ as God and Savior? Wrote Hodgson, “If we once begin doing this kind of thing, would there be any end to it?” (Ibid, 79). Finally, Hodgson wrote that the Movement doesn’t necessitate setting aside all differences. Instead, it allowed for people from different churches to stand side-by-side and even highlight differences; not with the goal of eliminating or washing them over, but with the goal of understanding and to “speak the truth in love” (Ibid, 80).

Bonhoeffer wouldn’t attend the conference, and while he would reach out to Hodgson four years later in 1939, Bonhoeffer would again be met with the kind of “open to interpretation” answer Hodgson gave in the letters of 1935.

This fascinating historical insight into arguing over the inclusion (or not) of a church literally overtaken by Nazis should serve as at least a partial warning to those interested in ecumenism. And, again, I am largely favorable to the idea. But is it possible that the definition defended by Hodgson is too broad? Or, is it possible that Bonhoeffer’s own certainty was too strong? I don’t think the latter is true. It should be possible for someone to look at a church body and say “the teaching as well as the action” of some church body, Christian leader, or whatever can be defined as no longer reflecting Christ as God and Savior. But how does one go about doing that? And how much should a body like the World Council of Churches stand back from seemingly intramural conflict?

Surely in today’s era, there are American churches that would label others as outside the bounds of Christianity or serving the Antichrist. Anti-LGBTQ+ church bodies might say that affirming church bodies are un- or anti-Christian and vice versa. The rise of Christian Nationalism begs the question of how one can serve two masters–the Nation State and Christ. The prominent sacrifices of orthopraxy for the sake of purported orthodoxy could yield countless other difficulties even as those who claim orthodoxy for themselves argue the contrary.

All of this is to highlight what is a very frustrating situation in which we find ourselves. It is one in which we cannot easily navigate our Lord’s wishes that we might truly be one. One temptation is to give it all up and say we may just have to wait for the eschatological future in which Christ will be all in all before any of this happens. But is it worth just giving up? I don’t think that’s the case, either. Instead, I think it is worth seeing this back-and-forth between Bonhoeffer and Hodgson about a church literally overrun by Nazis as a warning. What is confessed with lips must also be done in deed. What that means for ecumenism is something we must work out with fear and trembling.

[1] Fun fact- Hodgson unsuccessfully proposed to Dorothy L. Sayers. I couldn’t see that on Wikipedia and not share it.

[2] Simply an alternate spelling of ecumenical.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

John Warwick Montgomery (1931-2024)

John Warwick Montgomery died on September 25, 2024. John Warwick Montgomery is the most well known apologist from Lutheran circles in decades. From within the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, he fought not just external threats to apologetics, but also internal ones. As a Lutheran, he was forced by turns to defend even the prospect of apologetics from those who would lean towards fideism or some form of Lutheran irrationalism.

Montgomery was highly prominent in discussions about apologetic method. When the presuppositional method arose within Reformed circles, Montgomery was perhaps its most vocal and engaging critic. His famous (or infamous, depending on one’s stance) essay “Once Upon an A Priori” used fables to engage with presuppositional method and showed that the method would likely collapse under its own arguments when faced with an equally staunch presuppositionalist from another faith tradition. He wrote quite a bit in defense of evidentialist apologetics, and generally believed and argued that the Resurrection was historical fact and can and should be investigated as such.

Inerrancy was another of Montgomery’s pillars of argument. He argued against positions which would qualify inerrancy more, and attempted to defend it within the Lutheran tradition. He argued against other Lutherans who left his own denomination, asserting that their changed stance on inerrancy was the “fuzzification” of inerrancy to the point at which it would become unrecognizable as such. Indeed, I find his arguments to that effect fairly convincing, and that is part of the reason I don’t hold to inerrancy; it simply does not work with how the Bible was written. Montgomery would vociferously disagree, but I’m thankful to him for clarifying quite adroitly how qualifying a position like inerrancy begins to make it difficult to pin down.

Montgomery was a lawyer as well. He wrote on a vast range of topics, from law to demonology, from apologetics to historiography. His texts show a man whose mind was capable of absorbing and expanding on countless theologically-inclined topics in ways that, if they didn’t reflect particular expertise, still would show a general grasp of the topic and drive engagement with it. I have read and re-read some of his books to the point where covers are beginning to fall off. It’s often popular to read only those with whom one agrees, or to read one with whom one disagrees only to challenge and condemn. Montgomery, for me, is a constant challenging duelist. Where I disagree, I continue to find reading his works fruitful and challenging. Where I agree, I find pleasure in seeing his defense ably lay out points of impact.

I had the pleasure of meeting him at a conference in 2012. He was friendly and vivacious. The lecture he gave on religious conversion was fascinating to me at the time. I wrote up the lecture notes for a blog post here, and he sent me an email about my post, apparently thinking I had simply re-posted his lecture. He wrote, “Can you inform me as to where you obtained it and whose permission you obtained for doing so? I am willing to have you retain it on your website–but I need to know your source for posting it.” I wrote him back, explaining I had based my post upon my own notes based upon his lecture. His response was gracious, and to the point, thanking me for my detailed response and exposition of his lecture. It was my last interaction with him–I wish I’d had the courage to e-mail him again later.

Montgomery’s voice will be missed. He was an able defender of his positions and his mind wriggled into the logical holes in others’ positions in ways that made it uncomfortable to disagree with him. I admire the man, and I hope to see him in the hereafter.

SDG.

Links

John Warwick Montgomery– See all my posts tagged about John Warwick Montgomery (scroll down for more).

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“Bearing Sin as Church Community: Bonhoeffer’s Harmartiology” by Hyun Joo Kim- A fascinating look at the doctrine of sin through Bonhoeffer’s theology

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology continues to contribute enormously to discussions of theology today. What is especially rewarding about the work being done on Bonhoeffer’s corpus is finding topics that haven’t been explored as deeply as others. Hyun Joo Kim’s Bearing Sin as Church Community: Bonhoeffer’s Harmartiology specifically explores Bonhoeffer’s theology for the doctrine of sin, and the book richly rewards careful reading.

One of the central beliefs of Lutheranism, Catholicism, Calvinism, and several other branches of Christianity is that of original sin. For my own part, I find it an incredibly fruitful doctrine when contemplating the state of the world. Humans are incredible adept and finding imaginative ways to bring harm to each other. The horrors of the world are immense, and for me, one way to explain humanity’s awfulness to itself is to hold to a notion of original sin. Bonhoeffer’s views, by Kim, also make the position of original sin less incredible to believe, particularly in regards to explaining how it works. Instead of being linked to a (likely non-extant) original human couple, or being passed along through intercourse, Bonhoeffer’s view makes original sin and the Fall linked to human community and brings it into his ecclesiology. It all helps lend itself to his broader ethical stance, while still preserving the Lutheran view of original sin and guilt.

Before diving into Bonhoeffer’s doctrine of sin (harmartiology), Kim dives into the Augustinian doctrine of original sin. Augustine’s doctrine of original sin is closely linked with the notion of concupiscence–original sin as being transferred through the act of intercourse. Obviously, there is much more to it, but for Augustine, explaining original sin eventually boiled down to a kind of generational passing down through the act of intercourse itself. This saddled the doctrine of original sin with quite a bit of theological and other baggage. Kim then outlines Luther’s move from Augustinian original sin to a shift of seeing original sin integrated within Luther’s Christocentric theology. In essence, Luther’s focus on Christocentrism leads to a holistic theology that, while maintaining several aspects of Augustine’s view of original sin, centers Christ even in the doctrine of original sin. Luther’s view already started driving a wedge between concupiscence and original sin because while he apparently viewed the former as an essential aspect of transmitting the latter, he also held that original sin is forgiven in Baptism but that concupiscence remains a powerful influence on humankind (43).

Next, Kim turns to Bonhoeffer’s view of original sin. This includes a rejection of concupiscence as the basis for original sin. Rather than framing original sin in the “the biological and involuntary transmission of culpability…” Bonhoeffer frames original sin in “the relational and ethical bearing of the sin of others” (71). One of the main aspects of Bonhoeffer’s ethic is that the Christian has freedom for the other, and in this case, his doctrine of sin echoes that but in the bearing of sin for the other; it remains an alien guilt imputed, but a guilt nonetheless. Bonhoeffer’s reflection on original sin moves the alien culpability of Augustine’s doctrine of original sin from the sovereignty of God and to the church community. For Bonhoeffer, “the culpability of Adam is not biologically inherited; however, it is inseprably related to all human beings individually and corporately by the universal sinfulness after the fall” (72). This has some relation to Orthodox understandings of the fall [so far as I know from thinkers like Richard Swinburne–I admit very little direct knowledge of Orthodox teaching on the topic]. Bonhoeffer’s move, however, neither requires an original couple from whom all humanity is descended, such that the culpability can be passed down from one to another like a genetic lineage; nor does it need a specific means by which the original sin can be passed along. By sidestepping these two issues, essentially assigning guilt not to the individual through inheritance but rather through the very nature of humanity as sinful beings, he avoids many of the modern challenges to original sin, such as the question of human evolution–despite this clearly not being in Bonhoeffer’s mind as he wrote about the doctrine.[1]

Kim does draw some distinctions between Bonhoeffer’s earlier thinking on the doctrine of sin and his later theology, but to me these largely seem to be things that could be reconciled together as a continuum of the same theology. And of course the whole story is not told simply through Bonhoeffer’s views on original sin. Quite a bit more is featured on Bonhoeffer’s thoughts on sin and Christian life and ethics. Kim pays careful attention to Bonhoeffer’s book Creation and Fall and his exegesis of the Genesis narratives here. Kim’s argument is that Creation and Fall exists in the same sphere as his other works, Sanctorum Communio and Act and Being, and as such, it focuses on communal personalism and still integrates aspects of Lutheran and Augustinian notions into the reading.

Bearing Sin as Church Community is an absolutely essential read for those wishing to dive deeply into Bonhoeffer’s theology. It also is an exceptionally powerful theological work that demands close and careful reading. It provides new ways forward in understanding some of the core doctrines of some branches of Christianity, and new challenges to those that do not hold those doctrines. Highly recommended.

Notes

[1] It seems fairly clear in reading Bonhoeffer’s corpus both that he was largely aware of scientific consensus on his day on various topics, which would have included the evolutionary lineage of humankind, and also that he was supremely unconcerned with scientific truths related to theology. For him, it seems, there was no conflict between Christianity and science unless Christians themselves decided to make such a conflict by purposely moving theology into the sphere of science (or vice versa) when that is an utterly inappropriate move. See, for example, his brief comments about science near the beginning of Creation and Fall.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.