Apologetics of Christ

Problems for the Minimal Facts Argument for Jesus’s Resurrection?

The minimal facts argument for Jesus’s Resurrection is one of the more popular arguments I’ve read–and learned–in apologetics-related circles. Basically, it goes like this: there are certain facts which the majority of scholars agree upon regarding Jesus’s resurrection such that, when considered together, make the resurrection the most reasonable or only possible explanation of the facts. I have personally used this argument to great effect and for some time thought it a fairly strong argument. However, I believe there are some problems with the argument. These make me hesitant to continue using it as I did before.

I was considering the minimal facts argument recently and something a philosopher* said stuck with me. Namely, that the minimal facts argument conflates sociology with epistemology. Now, what does that mean? Essentially, it means that the argument attempts to use a sociological method–counting up which scholars believe (or don’t believe) a certain historical fact occurred–in place of epistemology–“it is reasonable to believe x.” I’ve oversimplified this, because I want readers to think more about the problem than about my wording of it. This is important, because A) I’m not an epistemologist and so don’t have the skillset to present the point as well as one with training in that area would and B ) I think it’s still a powerful objection that needs to be weighed instead of debating my own wording of the argument.

It shouldn’t be downplayed that this at least appears to be a major problem. The minimal facts argument essentially smuggles in a kind of epistemology along with the sociological data. In other words, the skeptic–or Christian–is expected to move from “the majority of scholars believe these facts” to “these facts are reasonable for me to believe.” Or, minimally (sorry), that “it is reasonable to believe these facts.” But without an epistemic support system, once the argument is laid bare like that, it seems almost farcical. While I’d not go so far as to say it’s logically fallacious,** it does have the look of an unwarranted move.

Another way the argument conflates epistemology with sociology is just that–it essentially treats the counting up and tallying of scholars*** as a genuine way to find and ground knowledge. And while this may not seem entirely unreasonable–after all, I would tend to see a significant majority of immunologists agreeing that a vaccine is safe and effective as a good reason to believe that myself–the move itself needs more argument. Moreover, because the argument is dealing with historical facts, it has additional wrinkles to the move from “scholars think x” to “it is a fact that x.” The aside about vaccines is a good counterpoint, because it is possible to physically test and confirm scholars’ opinions in that regard. However, for an historical fact, the opinions of numerous scholars about whether an event took place stands on somewhat less firm ground. As someone interested in historiography, myself, I realize it is tenuous ground indeed.

In most popular versions of this argument, there’s a kind of hand-waving that occurs regarding these minimal facts. The argument goes that a “majority of scholars” agree upon whatever fact. That fact may be, for example, that the disciples believed Jesus appeared to them after his death. Another fact may be that Jesus died from crucifixion. Now, let’s say of 100 scholars of history, 95 believe the first, and 95 the second. That’s a great majority! They may not be the same 95, of course, but 95 is still a solid number. The more facts that get introduced/discussed, the more acute this problem seems. So, let’s say you introduce the empty tomb, and 85 scholars believe in that. Are they all included in the other 95? If not, does it seem to take away something from the argument? I believe it may, though I’m not sure I can put my finger on exactly what the problem is.

Another issue with the argument, and the epistemology/sociology point is relevant here, is that the opinions of scholars is subject to change. I’ve read before how in many fields of science it often takes a generational shift before a theory can be fully accepted, despite massive evidence for its being true. The reason is because people tend to cling to what they know–or believe–to be true even in the face of evidence to the contrary. What this means for historical scholarship is that it is entirely possible, generation to generation, that the “majority of scholars” could have rather large shifts in opinion. If, for example, death by crucifixion were to drop off the map for a majority of scholars in relevant fields, would that mean it is unreasonable to believe that Jesus died by crucifixion? Hardly. But according to how this argument is used, it would be. Or, perhaps, it would seem to be.

Questions about what is meant by “majority” abound, though in the strictest and strongest versions of the minimal facts argument, the entry point for “majority of scholars” is kept quite high instead of appealing to any amount over 50%. When one considers this, though, it again makes the problem of arbitrariness loom. Who gets to determine what percentage of scholars is required for reasonable acquiescence on the part of laity? And are those scholars in the minority inherently irrational for disagreeing?

There’s also the question of how the scholars themselves are being represented. For example, is it really true that all scholars lumped together as agreeing about Jesus’s death by crucifixion actually agree to the same minimal fact in the same way? Maybe. But it’s hard to know unless one is presented with exactly how the question is presented to the scholars and what they said in response. This seems a minor point, until one begins to explore what could be meant by it. Jesus died by crucifixion seems straightforward, but the mental baggage that comes with that sentence for many people is huge. Of course, one could potentially counter this by saying “But what is truly meant is, on the simplest level, simply that Jesus died by execution on a cross. Surely that’s simple enough that we can know whether a scholar believes that or not.” I basically agree with the heart of that, but still wonder about things like whether those scholars would agree about what is meant by “Jesus,” for example. I don’t mean whether they believe Jesus is God in human flesh–that’s beyond what I mean. Instead, I wonder whether some of those scholars in the “agree” category might say “yes, there was probably a first century man named Jesus who was executed by crucifixion.” But would they agree that was the Jesus born of Mary, with Joseph as (surrogate) father, and even other details? I’m not so sure about that. And that does make a huge difference. Moreover, without seeing the method behind how we got “majority of scholars” in agreement about this very basic historical claim, it’s difficult to analyze it in any meaningful way.

All of this is to say that I think we ought to be quite careful in our use of the minimal facts argument. I’m not entirely convinced we should be using it at all, to be honest. Much scholarly work needs to be done to lay the groundwork for the argument, and a surprising amount of that groundwork needs to be on the side of epistemology, because one of the biggest problems is that the argument itself doesn’t seem to do the work it claims to be able to do. Finally, because it is unfortunately the case that questioning people’s beliefs happens when one questions established apologetic arguments, I want to very clearly say that I believe Jesus physically rose from the dead and that that is an historic fact. I am just unconvinced that this argument is the way to establish that.

*The philosopher was Lydia McGrew. I credit her with being the on to point out this problem to me and several others. I’ve expanded on some reflection on that here.

**I’ve seen some claim it is basically an argumentum ad populum or appeal to authority, but the former is inaccurate given that the argument is, in its strongest form, based upon actual scholars in relevant fields and the latter is a mistake because appeal to authority is only fallacious when it is done, er, fallaciously.

***I mean this literally, because some apologists (notably Gary Habermas) have done extensive work literally tallying up opinions of scholars in relevant areas to make the argument.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Jesus, the Demon-Possessed Man, and Christology- Luke 8:26-39

A recent reading in church struck me because I’ve been in conversations with some who deny the deity of Christ of late. The reading was from Luke 8. Verses 38-39 are what caught my attention:

The man from whom the demons had gone out begged to go with him, but Jesus sent him away, saying, “Return home and tell how much God has done for you.” So the man went away and told all over town how much Jesus had done for him (NIV).

Did you catch that? Jesus says “tell how much God has done for you.” How does the man respond? By telling what Jesus had done for him. The text goes to a different story immediately after this. There is no correction of the man’s behavior or any implication that the man did the wrong thing. Jesus tells him to speak of what God has done, and he obeys by telling what Jesus had done. Who, then, is Jesus?

One may respond by saying that Jesus is the means by which God healed the man. Thus, it was proper for the man to speak of Jesus without implying that Jesus is God. However, this misses the crucial linking of the terminology: the parallelism in “how much God has done for you” with “how much Jesus had done for him” is quite clear in both the English translation and the Greek original. This parallelism does not suggest any kind of difference between the two, or some kind of intermediary in between the two.

Thus, it appears that here in Luke we have a subtle acknowledgement of the deity of Christ.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Jeremiah teaches that the Messiah is God

“In those days and at that time

I will make a righteous Branch sprout from David’s line;

he will do what is just and right in the land.

In those days Judah will be saved

and Jerusalem will live in safety.

This is the name by which it will be called:

The Lord [ Hebrew = YHWH] Our Righteous Savior.’” – Jeremiah 33:15-16 (NIV)

These verses are clearly a prophecy about the coming Messiah. They also clearly state that that Messiah, a human from David’s line, will be called YHWH. In other words, this prophecy proclaims, hundreds of years before the birth of Christ, that the savior would be God incarnate. The one from the branch of David will be called YHWH, the righteous one.

Did the Son have a beginning? – Origen vs. heresies

Image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Origen3.jpg – Public Domain

Origen (184-253 AD) was one of the earliest defenders of the Christian faith.* In his work, Contra Celsum, he engaged with a Greek skeptic who brought many arguments against Christianity. In his De Principiis, he laid out the foundations of the Christian faith. (Both works are availble in The Works of Origen.) The latter work demonstrates key points to understanding the relationship between God the Father and God the Son:

John… says in the beginning of his Gospel, “And God was the Word, and this was in the beginning with God.” Let him, then, who assigns a beginning to the Word or Wisdom of God, take care that he be not guilty of impiety against the unbegotten Father Himself, seeing he denies that He had always been a Father, and had generated the Word…

This Son, accordingly, is also the truth and life of all things which exist… For how could those things which were created live, unless they derived their being from life? (Origen, De Principiis, Book I Chapter 2)

Origen, then, notes that the very descriptor of “Father” for God the Father entails that the Son has always been generated. Otherwise, one must deny that God was always the Father. But in that case, the Son must also always have been. And to deny this, one would have to deny creation itself, for all things were made through the Son.

Again, this point must not be lost: Origen, one of the earliest defenders of the church, saw the Father and the Son as distinct from each other and also co-eternal. Effectively, this goes against many false teachings, including modalism (the idea that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are different aspects of one God), any form of Arianism (that Jesus is not fully God), and the like. For a modern example, Jehovah’s Witnesses teach that Jesus is not fully God and not co-eternal with God the Father (whom they call Jehovah). Origen would repudiate this, noting that the Father can only right so be called in eternity, which entails the Father has always been the Father, and so the Son is co-eternal with the Father.

Reading many of these ancient historians reveals much truth about Christianity and helps to correct false teachings of today. I recommend readers read the Works of Origen.

*Origen did hold many unorthodox views which were later condemned as heretical. His faith was clearly one influenced by Platonic thought in which the human soul pre-existed and was eternal. Moreover, his view of the relations between the persons of the Trinity is deficient on many levels. My point in this post is specifically to show that Origen showed that the Son is co-eternal with the Father.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Faith is Belief Without Evidence? Origen contra Boghossian (and others)– Origen countered the claim that faith is to be categorized as belief without evidence, as many atheists continue to claim to this day.

Eclectic Theist– Check out my other blog for posts on Star Trek, science fiction, fantasy, books, sports, food, and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

What evidence should we expect about Jesus? Smithsonian Magazine answers

I was browsing magazines at the library and saw the cover of the January/February Smithsonian (pictured). I grabbed it because it caught my interest with the article title. What impressed me most, however, was the several points made within the article. Though it at times took a conspiratorial tone, overall the point of the article was to show what daily life would be like in 1st Century Palestine.

One of the most interesting points is one that I think is often missed by the recent resurgence of those who are arguing that Jesus never existed. Namely, what kind of evidence should we expect to find when looking for the historical Jesus (if any). From the article:

“The sorts of evidence other historical figures leave behind are not the sort we’d expect with Jesus,” says Mark Chancey, a religious studies professor at Southern Methodist University and a leading authority on Galilean history. “He wasn’t a political leader, so we don’t have coins, for example, that have his bust or name. He wasn’t a sufficiently high-profile social leader to leave behind inscriptions. In his own lifetime, he was a marginal figure and he was active in marginalized circles.” (49, cited below)

I think this quote shows much of the confusion that exists in Jesus mythicist circles. We can’t read 21st century expectations onto 1st century realities. Although Jesus is certainly an influential figure now, when he was crucified, he had disciples who had abandoned him and the only followers who stayed with him were women. Women were seen as unreliable witnesses in that time and place, and so the notoriety of Jesus, was of course, quite low. He was another messianic figure who had been crucified. It was only when some of these same women claimed to have seen the Christ as the first evangelists, spreading the message to the aforementioned disciples and beyond, that the message and fame of Jesus began to spread.

We cannot measure the evidence for Jesus’ life by what we would expect of similar figures today–or, worse–of what we’d expect from someone with Jesus’ influence now.

Source

Ariel Sabar, “Unearthing the World of Jesus” in Smithsonian (January/February 2016).

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Eclectic Theist– Check out my other blog for my writings on science fiction, history, fantasy movies, and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Constantine’s Faith and the Myth of “Constantine’s Takeover”

There is a narrative within some branches of Christianity (and some… “offshoots”) regarding church history. It is a narrative in which Constantine is seen as the great evil (whether intentionally or not) which corrupted Christianity. The narrative basically goes like this: Constantine rose to power, then everything went wrong in Christianity. He made Christianity the state religion, which introduced scores of nominal Christians into the church. He made service in the church a well-paying position, which corrupted the office of the ministry. He himself was probably not even a Christian!

There is a narrative within some branches of Christianity (and some… “offshoots”) regarding church history. It is a narrative in which Constantine is seen as the great evil (whether intentionally or not) which corrupted Christianity. The narrative basically goes like this: Constantine rose to power, then everything went wrong in Christianity. He made Christianity the state religion, which introduced scores of nominal Christians into the church. He made service in the church a well-paying position, which corrupted the office of the ministry. He himself was probably not even a Christian!

So the story goes. Is it accurate?

From Narrative to History

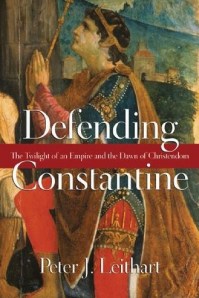

The question of Constantine is one of history. Too often, people have subjected Constantine to psychoanalysis, analyzing an ancient historical figure’s mental state to determine his motives. Historical study may indeed speculate about such things, but to suggest, as some do, that one may uncover some nefarious ancient plot to take over Christianity and lead it into heresy is to engage in writing historical fiction. So what may we actually learn from the historical accounts? Peter Leithart’s work, Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom directly addresses this question to pursue the “real” Constantine.

Leithart notes that it seems clear that Constantine actually paid much deference to Christianity (Leithart, 93; 121ff; 128-129; 326-328, etc., cite below). He was keen to prevent major divisions within the Church which could have resulted, for example, from the Arian controversy. Hence, he called a council at Nicaea which would define Christian orthodoxy for centuries to come. Constantine himself likely favored the view of Arius, but when the Nicene Council ultimately came against Arianism, Constantine submitted to the defining of orthodoxy.

Constantine’s life appears to be one not of a plot to take Christianity over for political gain, but rather as a life lived struggling with newfound faith and attempting to integrate that faith into public policy. Alister McGrath notes that Constantine’s faith led him to legalize Christianity and sanction it, with some interesting and perhaps unforeseen side-effects:

The new imperial status of Christianity meant that its unity and polity were now matters of significance to the state. (McGrath, 139, cited below)

The much-discussed question of why, if Constatine’s faith were genuine, he would have waited until his deathbed to get baptized is easily answered by his belief that he should wait until the last possible moment to gain the purifying from sins which baptism would provide (Leithart, 299-300).

Frankly, the more one reads about Constantine, the more difficult it becomes to imagine him as someone whose faith was not genuine. Like any Christian, he had his faults–he was a sinner-saint–but he also worked through his position to try to spread and unite Christianity. Leithart notes that many of Constantine’s laws were “more often Christian in effect than in intent” (304). What he means by this is that many laws he made spring from a Christian worldview, though not being explicitly Christian themselves. For example, he outlawed gladiator shows–hardly something which can be said to be explicitly Christian–and this demonstrated Constantine’s genuine concern for human life and the “image of God” in humanity which was noted in yet another law he made (303-304).

In another work, a collection of essays on Apologetics in the Roman Empire, Mark Edwards, having traced various lines of thought in Oration to the Saints (and arguing that it was a work by Constantine), notes:

[The work] reveals an emperor who was able to give more substance to his faith than many clerics, and an apologist whose breadth of view and fertile innovations make it possible to mark him with the more eminent theologians of his age (275).

It’s time to set aside the notion that Constantine was somehow “faking it.”

Constantine’s Takeover?

Constantine’s Takeover?

The “narrative” of Constantine has, unfortunately, often dipped into the notion that he was indeed a Pagan who overthrew traditional Christianity and condemned Christianity to political power-plays for centuries after his death. This notion simply does not line up with historical reality. Although Constantine’s enriching of the church’s coffers did lead to church positions becoming a political gain, it also provided a counter-balance to Imperial authority (Leithart, 304).

Moreover, Leithart argues that the notion that Constantine himself brought about so many wrongs to the church is historically fictitious: “[T]here was a brief, ambiguous ‘Constantinian moment’ in the early fourth century, and there have been many tragic ‘Constantinian moments’ since. There was no permanent, epochal ‘Constantinian shift'” (287). Indeed, the notion of church and state was something found seeded in Augustine’s writings (286) and although Constantine did bring about some monumental changes, the effects they had could only take place over vast amounts of time. It would be impossible to argue that the Catholic Church of the Medieval Period was directly the same or even the exact result of Constantine’s policy.

Finally, Constantine’s policies and actions “Baptized Rome” (Leithart, 301ff). He built churches, empowered bishops, called for unity, and deferred to church teaching. His laws, as noted above, were rooted in a genuinely Christian worldview and sprung from faith.

Conclusion: Defending Constantine

Was Constantine a perfect human? Obviously not. But was Constantine a Pagan who dramatically undermined Christianity; was he a usurper of the Church’s authority who did incalculable damage to Christianity? It does not seem so. Whatever your views on the matters, one must contend with strong historical evidence for the genuineness of Constantine’s faith. His policies indeed may have (and at points certainly did) damage the church, but was that his intent? Again, psychoanalysis of ancient figures is dubious, but the actions Constantine took were those of someone with genuine concern for the stability of Christianity. Most telling, perhaps, were his actions that were not explicitly stamped with Christianity but reflective of his background beliefs: by seeking to end violence, help alleviate poverty, and the like, he demonstrated his faith.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Sources

Peter Leithart, Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom

Alister McGrath, Heresy: A History of Defending the Truth (New York: HarperOne, 2009).

Mark Edwards, Martin Goodman, and Simon Price, eds., Apologetics in the Roman Empire (New York: Oxford, 1999).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “How God Became Jesus” edited by Michael Bird

Bart Ehrman has made a name for himself through critical scholarship of Christianity. His latest challenge, a book called How Jesus Became God, contains an argument that the notion that Jesus is God was a later development in the church and not reflective of the earliest teaching. Interestingly, the book was published alongside a response book, How God Became Jesus, in which multiple scholars argue that, far from being a late development, high Christology was the belief of the church.

Bart Ehrman has made a name for himself through critical scholarship of Christianity. His latest challenge, a book called How Jesus Became God, contains an argument that the notion that Jesus is God was a later development in the church and not reflective of the earliest teaching. Interestingly, the book was published alongside a response book, How God Became Jesus, in which multiple scholars argue that, far from being a late development, high Christology was the belief of the church.

The book is a series of essays organized around responding to Ehrman’s book essentially point-by-point. Ehrman’s central thesis, that Jesus Christ was exalted from human to deity over the course of theological reflection and some centuries, is directly confronted in a number of ways. First, Michael Bird challenges the thesis by pointing out some major errors in the Ehrman’s use of angels and other exalted beings. Later, a kind of death blow is dealt to the thesis by pointing out that even within the earliest writings there is the alleged full “range” of development of the doctrine of Christ as divine (136ff). Simon gathercole provides interesting philosophical insight into the use of types of change in relation and actuality (114-115).

Other challenges brought against Ehrman include critical analysis of his methodology (Chris Tilling, 117ff), historical insight into the development of orthodoxy (Charles Hill, 151ff), and insight into Christ’s own claims of deity (Bird, 45ff). These present a broad-spectrum approach to analysis of Ehrman’s arguments and demonstrate the difficulty of maintaining his thesis. Readers are exposed to methodological, factual, exegetical, and other errors in Ehrman’s work.

However, the book should not be seen merely as a response to Ehrman. Although it is structured around just such a response, it is a worthy read in its own right because it provides background for exploration of the deity of Christ found throughout Scripture. It also helps readers place these writings in context by showing the cultural surroundings of the discussions over the deity of Christ. Moreover, by analyzing many of Ehrman’s skeptical claims, the authors provide responses to a broader range of objections to the Christian faith. For example, Craig Evans’ essay on the evidences for the burial traditions provides insight into how crucifixion worked in practice and, importantly, how the Biblical narratives line up with these practices.

Various excurses provide documentary evidence for things like 2nd and 3rd century belief in Christ’s deity. These help to break up the book, which can easily be read chapter-by-chapter or as individual essays.

How God Became Jesus is a great read. It provides insight not only for a response to Ehrman’s thesis but also for a number of other issues that come up when talking about the incarnate Lord Jesus Christ. Each essay has much to commend it, and the excurses found throughout provide ways forward to research various other topics. The book is a solid resource for those interested in the deity of Christ.

My thanks to Baker Book House for the book as a gift. Check out their awesome blog to read a number of theological posts a week.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Source

How Jesus Became God edited by Michael Bird (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2014).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Dying for Belief: An analysis of a confused objection to one of the evidences for the resurrection

There is an objection to one of the evidences for the resurrection which is, frankly, terribly confused. I most recently ran into it on the discussion page for the radio show Unbelievable? Essentially, the objection goes like this: Christians say the fact that the disciples died for what they believe is evidence for its truth, but all kinds of religious people die for what they believe; are they all true?

There is an objection to one of the evidences for the resurrection which is, frankly, terribly confused. I most recently ran into it on the discussion page for the radio show Unbelievable? Essentially, the objection goes like this: Christians say the fact that the disciples died for what they believe is evidence for its truth, but all kinds of religious people die for what they believe; are they all true?

The objector then often proceeds to note that some Muslims will die in suicide bombings due to their beliefs; they will note events like Thich Quang Duc burning himself to protest persecution; they will note other events in which religious people die for their beliefs. The implication, it is alleged, is that this cannot count for evidence for the truth of what they belief. People die for false things all the time; it doesn’t make what they believe true.

The objection seems compelling at first because it is, in fact, largely correct. The simple fact that people are willing to die for something does not make whatever they are wiling to die for true. However, this objection shows that the objector is badly misrepresenting the Christian apologetic argument.

The apologetic argument is intended to be used against those who would allege that the disciples made up or plotted for the notion of the resurrection for some reason. It therefore presents a major disanalogy with people of other faiths (or even later Christians) dying for what they believe. The major difference is that the Christian is claiming the disciples who went willingly to their deaths would have known what they were dying for is false, if it were.

Suppose you and a group of friends decided to make up a story to get some money. You decided that you were going to pretend that a buddy had died and risen again. You managed to set up circumstances in which your buddy appeared to die; then smuggled him off to Argentina–because that’s where everyone likes to hide, apparently. Later, you ran about the streets proclaiming that you’d seen your buddy walking around. He had been risen from the dead. And, you’d tell the story for the right price. To your delight, the story spreads like wildfire. But eventually it attracts attention of the wrong kind, and people are coming to kill you. Now, suppose that you could easily get out of it alive by simply confessing you’d made up the whole story. What would you do?

Alleged explanations for the evidence for the resurrection which appeal to purported conspiracies are much like this. The disciples would have known they were lying. Thus, the fact that they willingly went to their deaths does indeed count as evidence for the truth of what they were claiming. Otherwise, one would have to claim that these people quite seriously and willingly went to their deaths for something they knew was a lie they themselves had invented.

Thus, it is not enough for the objector to simply point out that other people die for faith not infrequently. That is not the core of the apologetic argument. Instead, they must argue for the implausible notion that the disciples willingly died for what they knew was a lie. It was not something they simply thought might be a lie; it would have been something that they were certain was false.

I do not think it is too far afield to suggest that the objection fails. It seems far more likely that they certainly believed what they professed were true, and they were in the unique position of knowing whether or not they were lying. Thus, the explanation of the resurrection is more credible than the explanation of a conspiracy. There are, of course, other attempts to explain away the historical argument for the resurrection, but those are arguments for a different time.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus” by Adam English – A Seasonably Appropriate Book Review

In the quest for the real Santa Claus, what is discovered more often than not is that he can assume any shape. He can accommodate anyone… (191)

There are many discussions floating around about the “real” Santa Claus, Saint Nicholas. I have a bit of a side interest in the topic because I was never a believer in Santa Claus and so I’ve always been interested in the reality behind the myth. So, when I received The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus

for Christmas last year, I was excited to dive in for the season this year

Perhaps the most interesting portion of the work is English’s discussion of the historiographical difficulties related to unearthing the historical Nicholas of Myra. The difficulty with discovering the “real Santa Claus”–Saint Nicholas–is compounded by the fact that Nicholas of Myra (the Nicholas in question) is often confused with Nicholas of Sion (10; 80; 120; 174). Historical accounts of the life of Nicholas have often conflated these two persons, which means historians must extract them from each other in order to make an account of either. English confronts the possibility that Nicholas did not exist–a possibility put forth by some scholars, in fact–head-on by noting the multiple, independent sources for his life. Although Nicholas did not leave behind a legacy of his own writings, the extant evidence, argues English, is enough to acknowledge his existence as well as a historical core of stories about his life (11ff).

English does a great job of reflecting upon the apparently historical narrative while also drawing out the legends and apologetic tales which grew up around the narratives. Throughout the book, he reports a number of stories related to the life of Nicholas of Myra. He reports these stories seemingly in order of legendary development. For example, the famous story of Nicholas’ gift of gold to three women in need (about to be sold into prostitution) received more embellishment as time went on (57ff). However, English does not always do a great job of making the distinctions clear when these various types of tales are discussed. Part of this is probably due to the historiographical difficulties noted above, but it would have been nice for English to at least offer his opinion regarding the stories he related as to which he felt might be accurate as opposed to inaccurate. At some points he does, but at others he simply offers a series of increasingly surprising accounts without any commentary as to the possible historicity of the accounts.

A central part of the work focuses upon the council of Nicaea and the famous incident of Nicholas’ alleged slapping or punching of Arius or a different heretic (Arian) at the event. English argues that it is unlikely that it would have been Arius, because Arius was not a bishop and so likely would not have been present at the council itself (101-107). Moreover, English believes that a different story, in which Nicholas reasons with an avowed Arian to change his view, is more likely the historical background for the story (107-109). Nicholas’ own place at the council is disputed, but his orthodoxy is acknowledged by all his biographers, and it is likely that he defended the orthodox position at the council itself (107ff).

Apart from his participation at Nicaea, Nicholas also, of course, performed the basic functions of a bishop, which at his time included helping to resolve issues in Myra and the surrounding area (115ff). He helped with the struggle against pagan belief and practice, and at this point some of the stories and legends of Nicholas of Sion were often intermixed with those stories of Nicholas of Myra (120-125).

English’s work also draws out the way that Nicholas of Myra has been adapted for multiple purposes and occasions. Whether this is through the adaptation of his apparently real, historical life to various theological discussions (including Aquinas) or legends which were developed to supplement his legacy and individual viewpoints, Nicholas’ story continues to have widespread appeal.

The Saint Who Would be Santa Claus is an interesting read on a compelling man. Perhaps the most interesting part is the frequent fusion of myth and legend with the historical account. Those interested in the life of the “real Santa Claus” should immediately grab the book for their collection.

Links/Source

Adam English, The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus: The True Life and Trials of Nicholas of Myra (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2012).

Saint Nicholas- A Christian life lived, a story told– I wrote about the interplay between myth and reality in the stories about Nicholas. I wrote about how the myth of Nicholas actually bolsters the Christian worldview by pointing toward our longing for the ideal.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Guest Post: Rev. Kent Wartick on “The Virgin Birth”

“Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son,

and they shall call his name Immanuel”

(which means, God with us). Matthew 1:28 ESV.

Familiar words to most Christians, aren’t they? Along with His Death and Resurrection, the virgin birth of Jesus is among the most celebrated and unifying events in all of Christianity. Nativity scenes can be found in front of Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Baptist, Methodist, and all sorts of churches of all denominations. The virgin birth is counted as among the fundamental doctrines of Christianity, and was important enough to be counted as one of the twelve articles of the Apostolic Creed. For centuries, the account that Jesus Christ was born of a virgin woman, Mary of Nazareth, was undisputed, at least as far as any known challenges can be documented.

But, then, along came the Enlightenment. With it came the idea that science and reason were the test of Scripture and all truth, and not the reverse. Therefore, if Scripture says that Jesus was born of a virgin, and that is not logical nor scientifically provable, then it must be rejected. Thus, the Jefferson “Bible” excludes any reference to the virgin birth as well as Jesus’ miracles, Deity, resurrection, etc. As time went on, through the historical critical method and other destructive methods of using reason not to teach but to judge Scripture, the Enlightenment principle of reason and science over Scripture slowly infiltrated the thinking of many churches. Surveys confirm this infiltration.

1998: A poll of 7,441 Protestant clergy in the U.S. showed a wide variation in belief. The following ministers did not believe in the virgin birth:

- American Lutherans- 19%

- American Baptists- 34%

- Episcopalians- 44%

- Presbyterians- 49%

- Methodists- 60%

2007-DEC: The Barna Group sampled 1,005 adults and found that 75% believed that Jesus was born to a virgin. 53% of the unchurched, and 15% of Agnostics and Atheists believe as well. Even among those who describe themselves as mostly liberal on political and social issues, 60% believe in the virgin birth. (Source for surveys.)

It is a great travesty in the Church today that many clergy find themselves looking at their positions only as a job, and will say what they must to preserve their positions. From the source of the polls previously cited comes this quote:

“…one Hampshire vicar was typical: ‘There was nothing special about his birth or his childhood – it was his adult life that was extraordinary….I have a very traditional bishop and this is one of those topics I do not go public on. I need to keep the job I have got.’

Such hypocrisy and blatant deceit is unworthy of anyone, let alone one who claims to proclaim the Word of God and represent Him to the people. yet such is the state of much of the clergy, as indicated by the above polling figures. No wonder the Church is in such disarray, and seems so powerless in the world today!

If Christianity is only a “nice” way of life that is only about love and compassion, then I suppose the virgin birth is not so essential, But if Christianity is an intimate and personal relationship by faith with the Creator of the Universe, then Who that Creator is makes all the difference. And if being born of a virgin is something He says about himself, even once, in His Book, then it might be best if we believe it. After all, wouldn’t you like to know a bit about, say, the pedigree of a dog or horse that you were to buy, or even more so, wouldn’t you like to know all about a future spouse that you profess to love before marriage? (Please forgive the analogy, which is not meant to cheapen God, spouses, dogs, or horses).

The virgin birth of Christ—and I would say, the historical fact that Jesus was conceived by a miracle like unto creation itself—does not travel alone. It ties intimately into other doctrines-the Holy Trinity, the Deity of Christ, the substitutionary atonement, the inspiration, inerrancy, and infallibility of Scripture, and more. “Scripture cannot be broken”, Jesus said in John 10:35. Even so, the most basic teachings of the Christian faith cannot be broken off and accepted like items on a buffet table. They are all one. Accept all of them-or none of them. That is the challenge that the catechumen, the seeker, the growing disciple of Christ is faced with. Finally, you see, the importance of the virgin birth is found, like all things, bound in the Person and Work of Jesus Christ.

As far as the prophecy quoted by Matthew, namely Isaiah 7:14, much ink has been spilled on this by scholars with more degrees than I have. Some modern Bible translations, notably the NRSV, CEB, TEV and others use “young woman” to translate the Hebrew word almah. Others, such as the NASB, ESV, NKJB, TNIV (=NIV 2011), use the more traditional “virgin.” The LXX also translates the word “virgin.” While the matter is not as simple as some might make it, certainly I would think that the Septuagint scholars would have known Hebrew and Greek well enough to have chosen a different word besides the Greek word for “virgin” if “young woman” would have been indicated. They had no agenda to support a virgin birth or not. The same cannot be said of some modern translators. The sainted Dr. William Beck wrote a study on this subject, available at www.wlsessays.net/.

Human reason helps us put all of these things together systematically from Scripture; but human reason cannot accept and believe them itself. That, too, is a special creative work of the Holy Spirit. What a delight to know that God wants everyone to know Him as He reveals Himself in Scripture. It is through the very words of Scripture that God creates faith. Through those Holy Spirit given and empowered words He keeps one in the faith. As I stand in awe that God chose this supernatural way to join our human race, so I stand in awe that He created faith in my heart, and has kept that faith to this day. All glory and praise to Him forever!

Finally, though, the virgin birth is a matter of faith. For the individual, it is a matter of personal faith whether one accepts what Scripture says about the miraculous conception and birth of Jesus or not. But the virgin birth is also a matter of THE Faith; that is to say, it is an article of Christian doctrine that is beyond dispute. To accept it is to accept a fundamental, essential doctrine of all Christianity. To reject it is to put one outside the bounds of the Christian faith. I pray that this Advent and Christmas season you will join with me, and with all the Christian world, in celebrating the supernatural way that God chose to enter our human race to bear our sin and be our savior.

Rev. Kent Wartick is the pastor of Faith Lutheran Church in Kent, Ohio. He has been preaching for over 26 years in the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod. He’s my dad, and an inspiration for the faithful.