Eschatology

Eternal Conscious Torment, Degrees of Suffering, and Infinite Punishment

One argument for affirming Eternal Conscious Torment (hereafter ECT) is that it allegedly makes more sense of divine justice.* So, for example, the argument is that awful dictators like Stalin or Hitler being simply executed by God (such as in some views of Conditionalism) is unjust, but rather their punishment must be much more severe in order to satisfy justice. To rework ECT and allow for a more palatable sense of justice, the concept of degrees of punishment is sometimes introduced, such that those who did not commit great atrocities suffer less than those who did. Another argument for ECT is that because God is infinite and God is the wronged party when creatures sin, those finite creatures must suffer infinite punishment for justice to be served. Below, I’ll argue that these arguments related to ECT fail.

Degrees of Punishment

Intuitively, it seems unjust that someone who say, did not come to belief in Jesus Christ due to not hearing the Gospel proclaimed have the same level of punishment in eternity as someone like Stalin does or someone who intentionally misleads people about Christ. Thus, the argument goes, to preserve that sense of justice, there are degrees of punishment in hell. Instead of debating the merits of that argument, I’d like to highlight a significant problem for the ECT position on this view. Namely, ECT does not, in fact, allow for degrees of punishment on the basis of it being eternal.

Eternity is a long time. It is infinite. Defenders of ECT are adamant: this punishment goes on forever, without end. However, once one introduces the infinite into real life situations, such as eternal conscious torment, some difficulties appear. To explain, examples like Hilbert’s Hotel can help explain some of these situations. In Hilbert’s Hotel, there are infinite rooms which are all full with infinite people. But, alas, a guest would like to check in! No problem, Hilbert just moves every guest down one room, thus making room for another guest! It sounds paradoxical because it is. That’s not how things in the real world seem to work. Nothing truly seems infinite.

For defenders of ECT, hell is infinite. Let’s say we have two people in ECT’s view of hell. One, Jill, has a degree of punishment significantly smaller than that of Joseph Stalin. Let’s say that Jill’s suffering is only 1/1000 that of Stalin. Now, to determine how much suffering any individual suffers, one can multiply the amount of suffering by the amount of time they’re suffering that amount. But infinity multiplied in such a fashion remains infinity. In both Jill and Stalin’s case, that amount of time is infinite. Thus, their total suffering is equal, because the quantitative suffering they receive moment to moment ultimately multiplies to be an equal, infinite amount of suffering. The aggregate suffering which each endures is infinite. All of the unsaved, regardless of who they are or what actions they did in this life, ultimately suffer an equal amount: infinitely.

This means that the argument about degrees of punishment related to ECT fails, because all of the lost suffer the same ultimate fate: infinite suffering.

Different Infinites

It is true that there are different kinds of infinities in math. However, those differences aren’t relevant in this case for a few reasons. One reason is that no individual’s suffering is infinite at any given moment (this is important, as we will see in the next section). That is, we can quantify one’s temporal suffering, say, on a range of 1-1000. Because of that, the calculus of infinites doesn’t change here. Though there are different kinds of infinite, the degrees of punishment being discussed here are not–and cannot–be significant enough to impact that ultimate amount of aggregate suffering in a way that makes the infinites mathematically discernable.

The other problem is that mathematical proof can show that the different type of infinites don’t matter in the case of ECT. See the Appendix below.

Infinite Suffering and the Justice of an Infinite God

Another argument in favor of ECT is that, because one has wronged an infinite being, the punishment must be infinite. If I’m right about the above problem for ECT, ECT succeeds at providing infinite aggregate punishment, but only at cost of undermining any possibility of degrees of punishment. But the fact that it is only aggregately infinite yields another problem: no finite being actually suffers an infinite amount, which undermines another argument for ECT.

Humans are finite–this is a given and indeed is part of the proponent of ECT’s argument for needing an infinite punishment for wronging an infinite God. However, because humans are finite, they are incapable of suffering, at any given moment, an infinite amount. So, while their suffering will be an aggregate or ultimate infinity, given the infinite time of eternity, at no point in time can one say “Stalin has suffered infinitely.” The reason for this is that, at any given moment in eternity, the amount of suffering would still be finite, having not yet reached an infinite amount. For every given moment, t, there is another moment, t +1, that would yield more suffering.

What this means, then, is that no one in hell, at any given moment, has suffered or will have suffered infinitely (excepting the abstract ultimate or aggregate eternity). But if God’s justice can only be served by meting out infinite suffering to finite creatures, then God’s justice is never satisfied, for all such creatures doomed to infinite suffering must continue to suffer without ever reaching the actual infinite amount of suffering. Therefore, the argument in favor of ECT from God’s infinite justice fails.

Addendum: Infinite Life in Christ

Another outcome of my reasoning is that degrees of reward in heaven must ultimately be the same as well. Thus, any view which deems it necessary for there to be varying degrees of eternal bliss faces the same difficulties as ECT does, for all of the saved will experience infinite bliss. Therefore, views of eternal rewards which rely upon infinite rewards fail.

*Interestingly, the opposite is also often held by those who argue for positions apart from ECT.

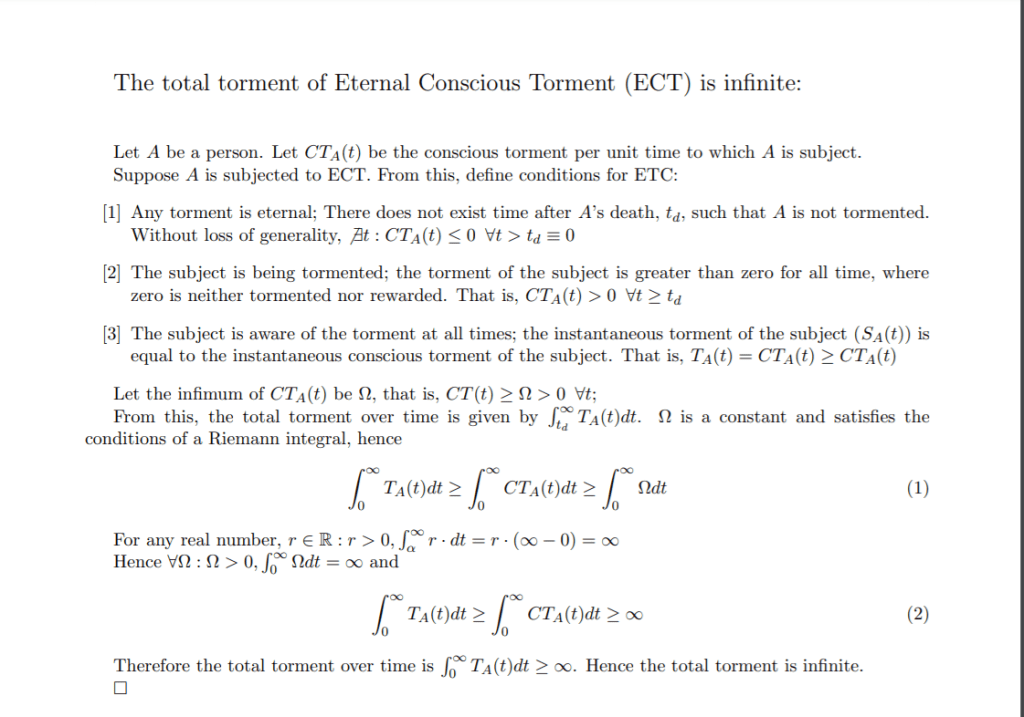

Appendix: Mathematical Proof and Infinite Suffering

This mathematical proof was made by Jonathan Folkerts, a Physics Doctoral Student.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Down with Millenarianism- Reconstructing Faith

There are theological stances that are worth making standards of faith. Increasingly, one’s view of the “millennium” is becoming one of the stances that schools, seminaries, universities, and church bodies are making a standard of faith. I cannot emphasize this enough: this is a terrible mistake.

When I was getting my graduate degree, I signed off on a doctrinal statement with reservations for the school I was attending. That statement, at the time, allowed one to disagree with the school’s position (premillennial dispensationalism) so long as they were willing to learn about that position. I was and am Lutheran and hadn’t learned much about any endtimes position, so was perfectly willing to agree to learn about their own teachings on the topic. That school’s statement of faith has hardened on eschatology, to the point where it now seems to imply that their own particular brand of premillennialism is one of those make or break, in or out views related to sound Christian teaching. It’s not.

One thing that immediately struck me as I was learning about the eschatological position of millenarianism more generally (reading some multiple view books, for example, to try to understand the different positions) was that the supposed plain and simple reading of the text I was told led to premillennial dispensationalism strangely yielded an untold number of divergent charts, timelines, and theories about exactly how it would all play out. One author was absolutely certain some events would happen in a seven day period, while another would say it would take place over 7 years, and another would have a timeline showing how the 7 days were correct but that they were not consecutive days. It was bewildering, coming from an outside perspective, trying to even understand the basics of why anyone would hold to such a view. Surely, if one’s view of eschatology and even the timeline of events of Revelation (usually borrowing selectively from parts of the Old Testament to bolster one’s case) is the clear reading of Scripture that anyone who was being honest about the Bible should come to, it shouldn’t be the case that basically every single adherent of the position would have slight or major differences in something as simple as when a major event should occur.

Of course, logically, divergence of opinion does not necessarily entail that a position is wrong or unclear. However, on the face of it, if someone makes a claim that something is clear and simple, and all the evidence at hand suggests that virtually no one can come to agreement on what this clear and simple fact means, then there seems to be very good reason to doubt that the initial claim of clarity is correct. And this, in part, is why I think we need to say “Down with milllenarianism.” Look, I have no problem with someone who wants to read about rapture theories or make some extensive timeline in which they splice a verse from Daniel into a prediction from Isaiah in order to clarify what sort of military hardware might exist in the endtimes. Go for it! But the problem is when people insist that everyone else must also do the same or else they’re rejecting God’s Word–that’s when it needs to be cut off (if not before). Here are some reasons I think we ought to be extremely skeptical of basically any form of millenarianism.

- Millenarianism is unnecessarily divisive. The fruit of the Spirit does not seem to include divisiveness. Moreover, it seems like millenarianism is producing “bad fruit” if it means that churches and people are splitting when they need not be.

- The forms of eschatology united with millenarianism are fairly recent innovations. In one theology class I took (I can’t remember which), the professor would often say that if some aspect of theology is new, it’s probably heretical. While it’s true that theological innovation continues to happen, when an entirely new way of reading portions of Scripture comes onto the scene that insists on being the one true teaching about the end times, we ought to be highly skeptical. While attempts are made to tie premillenialism to early church theology (see the Wikipedia page on premillennialism, for example, which humorously refers to Irenaeus as an “outspoken premillennialist”), these attempts are misguided and tend to read views back onto historical figures that they did not have. Shared theological statements on eschatology does not mean that an historical figure is a premillenialist. Premillennialism is a system of thought that makes numerous claims, and attempting to ground it in early church history either makes one confused or dishonest.

- Millenarianism reads Scripture poorly. Attempting to go through today’s headlines and find where they might be shoehorned into Scripture is effectively the exact opposite of how we ought to approach applying the Bible to modern times. Any number of books on eschatology, particularly those which attempt to elucidate the exact events of the supposed “Millennium,” do this constantly. Moreover, most forms of Millenarianism insist upon reading prophetic literature “literally,” despite overwhelming evidence that these writings were not intended to be read in that way whatsoever.

I think I could probably continue this list for quite a while, and each of these points will probably be endlessly debated, but this is the core of my objection. Millenarianism is divisive, a poor reading of Scripture, and suspect given its theological history.

I’ve written before about how I’m reconstructing faith. For me, a complete rejection of millenarianism is part of that. It is important to take God’s word seriously, and I think it’s time to take it seriously enough to reject the poor readings that most forms of millenarianism require. Insisting on reading the Bible in a way that it was never intended is to do damage to the word of God.

Links

Reconstructing Faith– Read other posts as I search for truth and navigate the messiness that is faith.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Bible Verses Edited for Eternal Conscious Punishment

The Bible has a lot to say about the final end of both the redeemed and the lost. It’s often said that the Bible is extremely clear on eternal conscious punishment–as though this is just read of the pages of Scripture and delivered as a whole doctrine to us. I have taken the liberty here of looking at a number of well-loved and well-known passages (and some lesser loved and known) through the lens of eternal conscious punishment, editing them as needed to actually support the allegedly biblical doctrine of eternal conscious punishment. Edits to the verses are in italics, to make it clear where editing has occurred.

The Bible has a lot to say about the final end of both the redeemed and the lost. It’s often said that the Bible is extremely clear on eternal conscious punishment–as though this is just read of the pages of Scripture and delivered as a whole doctrine to us. I have taken the liberty here of looking at a number of well-loved and well-known passages (and some lesser loved and known) through the lens of eternal conscious punishment, editing them as needed to actually support the allegedly biblical doctrine of eternal conscious punishment. Edits to the verses are in italics, to make it clear where editing has occurred.

John 3:16

For God so loved the world, that he gave his one and only son, that whoever believed in him should not have eternal life[the bad kind], but have eternal life [good kind].

Romans 6:23

For the wages of sin is eternal life [bad kind], but the gift of God is eternal life.

Matthew 10:28

Do not be afraid of those who kill the body but cannot make eternal the soul. Rather, be afraid of the One who can make eternal both soul and body in hell.

Revelation 20:13-14

The sea gave up the dead that were in it, and death and Hades gave up the dead that were in them, and each person was judged according to what they had done. Then death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. The lake of fire is eternal life.

Psalm 9:17

The wicked go down to eternal life, all the nations that forget God.

Matthew 25:46 (The Sheep and the Goats)

“Then they will go away to eternal life, but the righteous to eternal life.”

2 Thessalonians 1:9

They will be punished with everlasting life and shut out from the presence of the LORD and from the glory of his might…

Jude 1:7

In a similar way, Sodom and Gomorrah and the surrounding towns gave themselves up to sexual immorality and perversion. They still stand today because they were not destroyed and serve as an example of those who suffer the punishment of eternal fire.

Psalm 37:8-11

Refrain from anger and turn from wrath;

do not fret—it leads only to evil.

For those who are evil will live forever,

but those who hope in the Lord will inherit the land.

A little while, and the wicked will be still alive;

though you look for them, they will be found alive but suffering.

But the meek will inherit the land

and enjoy peace and prosperity.

Conclusion

Eternal conscious punishment is not a “literal” reading of Scripture, nor is it simply read off the pages of scripture. To affirm it, one has to effectively redefine the meaning of “death” and other words constantly throughout the Bible. Generally, this requires the one teaching eternal conscious punishment to turn the word “death” into “eternal life,” for they believe that the lost are given eternal life, just a kind that involves punishment.

Life as a Cubs Fan – Eschatology Fulfilled

I’m writing this as the Cubs are tied 1-1 in the 2016 World Series with Cleveland. I’ll be finishing it just after the World Series, and I hope beyond hope that it will be in celebration of a victory of the Cubs in the World Series, for the first time in 108 years. I’ll clearly mark the point I wrote after the World Series. Go Cubs!

I’m writing this as the Cubs are tied 1-1 in the 2016 World Series with Cleveland. I’ll be finishing it just after the World Series, and I hope beyond hope that it will be in celebration of a victory of the Cubs in the World Series, for the first time in 108 years. I’ll clearly mark the point I wrote after the World Series. Go Cubs!

There was one night I was in bed but could not fall asleep. I believe it was when the Cubs had just tied the NLCS 2-2 with the Dodgers. I was bubbling with joy because they’d just tied the series. It meant there was a chance, however remote, that the Cubs could make it to the World Series for the first time since 1945. It meant that, maybe, there wouldn’t have to be a “Next Year” this year. Maybe, just maybe, it could happen.

As I was lying there, thinking, I realized that it was at this point I truly understood the joyful anticipation that the writers of the New Testament experienced. Jesus Christ had promised to return, and soon. How great that joyful day would be! But each day, each year, there was the thought: there’s always tomorrow. One day we will experience the reality that there is no more tomorrow, and our joy will be complete.

With our eschatological hope, we know that there’s not just a chance. It’s a matter not of if Christ will return, but when. And that is something that I feel overjoyed about and also terrified. What does it mean to say Christ will return? The world will be not just a different place–a changed place–it will be made anew.

Post World Series

I just re-read a blog post I wrote back in 2012 entitled “The Eschatology of a Cubs Fan.” In that post, I wrote:

I still hold out hope though, it’s almost like an eschatological promise: “There’s always next year.” Boy, we’ve been saying that for a long time. But I really do believe it: one day, the Cubs will win one, and it will be during my lifetime. When they do, I’ll be like the fan standing up, looking at the skyline, and just rejoicing. I’ll say “This one was for you, grandpa” and I’ll see him sweeping the streets in heaven [my grandpa would get a broom out and sweep the floors when the Cubs swept a series]. If it happens, I will get to Chicago, I don’t care when it is or how it happens. I won’t have to be at a game, or even there while one happens, but I’ll get back to Chi-town, the place I love, and I’ll kiss the walls of Wrigley, wearing my “World Series Champions” hat.

One day, Cubs.

One day.

That day has come. I can’t believe it. I will write up a lengthy reflection on the win later, but for now I want to put it in perspective of this post. The consummation of so much hope, so many shattered dreams that suddenly got repaired, is one of the greatest feelings I’ve had in my entire life. But this is nothing to compare to that which will come at the final eschaton–the return of Jesus Christ. That’s not to say the World Series win for the Cubs doesn’t matter–far from it, the world really did change, and it feels new as I wake up each morning. What I’m saying, instead, is that this feeling, this joy, is one of the ways God gives us to see a greater thing to come. It’s a kind of typology, but one that can be found in the mundane–even something as simple as a human swinging a stick at a ball.

And that, really, is what Christianity (and, really, Lutheranism) is all about. Christ has come into this world, become incarnate, and is in this world now. Our God came and dwelt among us. And those blessings given us reflect God’s good reality, and a better one that is to come.

I think it is true that I, and many other Cubs fans, can now say we know what a slice of heaven looks like, what it feels like. Hope will one day be fulfilled. That long-awaited day shall come. Christ will return. Come quickly, Lord Jesus. Amen.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Eclectic Theist– Check out my other blog for my writings on science fiction, sports, history, movies, and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Bound for the Promised Land” by Oren Martin

Oren Martin’s Bound for the Promised Land is a canonical-perspective look at the land promise throughout the Bible. His central thesis is that “the land promised to Abraham advances the place of the kingdom that was lost in Eden and serves as a type throughout Israel’s history that anticipates the even greater land… that will… find… fulfillment in the new heaven and new earth won by Christ” (17).

The book advances a broad argument for this thesis by surveying what the Bible has to say about the land promise and its fulfillment. Martin does not offer a comprehensive look at every verse in the Bible that deals with the land promise, but rather puts forward a canonical view in which he surveys what various books of the Bible say about the promise and puts them in perspective alongside each other. He thus develops the promise from Eden in Genesis through Abraham, into Canaan, exile, through prophetic hope of return, the ushering in through Christ, and the ultimate consummation in the New Creation.

The book isn’t going to blow readers away with stunning insights. Frankly, that can be a good thing when it comes to theology texts. Martin’s exegesis is sound, based on firm principles and clearly drawn from the texts themselves. By connecting these verses to wider canonical strands, he demonstrates that his position is capable of dealing with the whole teaching of the Bible on the land promise rather than isolating it and trying to trump these threads with individual out-of-context verses.

Though not stunning or necessarily new, the insights Martin puts forward provide a great resource for those interested in eschatology and the issues raised by dispensationalists regarding the land promise. Martin does not support the dispensational view and argues cogently that it cannot be supported by the texts that teach on the land promise. The notion that we must take the land promise “literally” does not do full justice to the texts themselves and cannot account for the broadness of teaching on the topic.

Bound for the Promised Land is an insightful work that will lead to much flipping back and forth in readers’ Bibles as they go through it. I enjoyed making some new notes and re-highlighting some key points. Martin’s exegesis is solid, and the work is great for those interested in eschatology and biblical prophecy. By putting together a book focused exclusively on the land promise from a perspective that takes seriously the whole of biblical teaching on the topic, Martin has done a service for those interested in eschatology. I recommend it as a worthy read.

The Good

+Clearly outlines presuppositions the author maintains throughout the study

+Solid exegesis

+Canonical view gives picture of whole teaching of Bible on topic

+Applicable insights put forward

The Bad

-Skims over arguments very briefly at points

Disclaimer: InterVarsity Press provided me with a copy of the book for review. I was not obligated to provide any specific kind of feedback whatsoever, nor did they request changes or edit this review in any way.

Source

Oren Martin, Bound for the Promised Land (Downers Grove, IL: Apollos/InterVarsity Press, 2015).

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

The Binding of Satan: An Eschatological Question

When does the binding of Satan occur? Is it something yet to come, or is it something which has already happened? Here, I will analyze the futurist position on these questions: the notion that Satan and his minions are yet to be bound.*

When does the binding of Satan occur? Is it something yet to come, or is it something which has already happened? Here, I will analyze the futurist position on these questions: the notion that Satan and his minions are yet to be bound.*

Futurism is, essentially, the position that the prophecies in Daniel and Revelation (and many elsewhere) are largely yet to be fulfilled. This is in contrast to historicism– the view that these prophecies have been fulfilled through the church age (with some yet future); preterism– the view that many of these prophecies have already been fulfilled in the past; and idealism– the view that these prophecies have spiritual meanings which may be fulfilled multiple times through history until the End.

The central passage for the question at hand is Revelation 20:1-3:

And I saw an angel coming down out of heaven, having the key to the Abyss and holding in his hand a great chain. He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the devil, or Satan, and bound him for a thousand years. He threw him into the Abyss, and locked and sealed it over him, to keep him from deceiving the nations anymore until the thousand years were ended. After that, he must be set free for a short time. (NIV)

The futurist interpretation of this passage would be fairly straightforward: at some point in the future, before the millennium, Satan will be bound. Many futurists hold that this also includes Satan’s minions. Representative is Paul Benware: “With the removal of Satan comes the removal of his demonic forces and his world system” (Benware, 334, cited below). It is on this point that the question I have turns. Consider Jude 6:

And the angels who did not keep their positions of authority but abandoned their proper dwelling–these he has kept in darkness, bound with everlasting chains for judgment on the great Day. (NIV)

Note the interesting parallels with the passage from Revelation 20. Both use the language of “chains” and reference a time when something will happen after this binding. Yet Jude 6 seems to imply the definite binding of these demonic forces from the time it was written or even before. Why? Jude 5 gives the temproal context, which is sandwiched in between discussion of the Exodus and Sodom and Gomorrah. Of course, Sodom and Gomorrah predate the Exodus, but the overall context of the passage is given by Jude as being around that time period (“I want to remind you…” v. 5).

Moreover, 2 Peter 2:4 states:

For if God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell and committed them to chains of gloomy darkness to be kept until the judgment…

Again, in context Peter is discussing a number of past events. So it certainly seems that at least some demonic forces have already been bound. Benware writes of these passages: “The Scriptures reveal that Satan and his angelic followers will be judged for their sin and rebellion…” (329, emphasis mine). Now, Benware is clearly saying that there will be a judgment in the future, and that seems correct from both passages. However, he does not note anywhere in his major work the difficulty these verses present to his own view, for he insists elsewhere that amillenialists are incorrect when they view this binding as being a present reality (129ff). But he does grant that at least some demonic forces are bound now.

The question, then, is how is it that futurists can consistently insist upon the impossibility of Revelation 20:1-3 being a present reality while already granting that it is, at least in part, fulfilled? That is, if one grants that at least some demonic forces are bound, it seems that one cannot insist that certain spiritual forces cannot possibly be bound at present. Thus, it seems to me this particular aspect of futurism is not on as strong a ground as many insist.

Indeed, one may read Jude 6 and 2 Peter 2 and get the impression that these things have already occurred. There is no stipulation within the text to say that only some wicked angels have been bound. Indeed, they both seem to imply the total binding of all demonic forces. But this would not be compatible with the standard futurist interpretation of Revelation 20:1-3.

*Readers should note that I am not here intending to critique the overall futurist position. Instead, I am merely wondering about one specific aspect of some futurist interpretations.

Links

Check out my other posts on eschatology (scroll down for more).

Also, read my review of Benware’s massive work on premillenial dispensationalism, Understanding End Times Prophecy.

Sources

Paul Beware Understanding End Times Prophecy (Chicago: Moody, 2006).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Four Views on the Book of Revelation” (Zondervan Counterpoints Series)

I have been researching eschatology quite a bit of late. Please be aware, therefore, that this review comes from one who has only read a limited amount on the subject. I will not be offering insights from an expert, and am fully ready to admit that I am still learning. That said, I chose Four Views on the Book of Revelation

I have been researching eschatology quite a bit of late. Please be aware, therefore, that this review comes from one who has only read a limited amount on the subject. I will not be offering insights from an expert, and am fully ready to admit that I am still learning. That said, I chose Four Views on the Book of Revelation because I enjoy reading from different sides of debates like these. I think it is important to have an understanding of each position from proponents of the different views. I will here offer a brief review of the book. [If you decide to get the book, please use the links in this post support my ministry through Amazon.]

Overview of Content

Introduction

The work begins with a rather lengthy introduction to the book of Revelation and the various views regarding its content. The bulk of this section is its introductions to each of the views featured in the work. Interestingly, the historicist view is basically dismissed out of hand in the introduction:

This volume incorporates the current, prevailing interpretations of Revelation. Thus, while the historicist approach once was widspread, today, for all practical purposes, it has passed from the scene. (18)

Preterist View

Kenneth Gentry, Jr. begins his exposition of preterism with a bold claim: “I am firmly convinced that even an introductory survey of several key passages, figures, and events in John’s majestic prophecy can demonstrate the plausibility of the preterist position” (37). Before diving into this survey, however, Gentry outlines the importance of understanding that Revelation “is a highly figurative book that we cannot approach with… literalism” (38). He defends this claim with a number of points, including the precedent of earlier prophets who used symbolism and the difficulty of consistent literal readings (38-40).

Gentry’s case for preterism focuses squarely on the introduction to the book. This is not to suggest that is the only part of his argument, but rather than he himself recognizes the introduction as a central tenant of preterism. He notes the continued refrain of Jesus “coming soon” and argues that this suggests a reading of the text as real prophecies occurring within the lifetimes of those present.

Much of the rest of Gentry’s survey is built upon tying the prophecies in Revelation to the historical events of the attack upon Jerusalem. A good representation can be found in tying the “Beast” 666 to Nero and the seven mountains to Rome (67-69).

Idealist View

Sam Hamstra, Jr. argues that the core of the idealist view of Revelation is found in a message: “While at this moment the children of God suffer in a world where evil appears to have the upper hand, God is sovereign and Jesus Christ has won the victory” (96).

The idealist case centers around seeing Revelation as apocalyptic literature, and interpreting it through that lens (97). However, Revelation is not exclusively apocalyptic but is rather “a mixture of literary styles” (99). The idealist interpretation sees the use of “like” throughout the descriptions of Christ and elsewhere as supportive of the non-literal nature of the book (101ff).

Hamstra’s survey of the book of Revelation continues to note what he holds are the symbolic use of symbols and other imagery. Representative is the use of the number seven, which suggests “completeness… the author is speaking of the church at all times and in all places” (102).

For the idealist, then, the book of Revelation can have multiple fulfillment throughout time. It is a book which comforts Christians who see the constant wars, plagues, and the like seen in Revelation by reminding them that God is in charge. Ultimately, Pate’s view can be summarized easily: “the best understanding… is that Jesus’ utterances about the Kingdom of God were partially fulfilled at his first coming… but remain forthcoming until his return” (175).

Progressive Dispensationalist View

C. Marvin Pate’s progressive dispensationalism is grounded in the theme of “already/not yet” (135). This notion hints at eschatological tension which can be found throughout the book of Revelation, according to Pate. That is, there are things which may seem fulfilled “already” but have “not yet” reached their fullest completion. As an example, he notes “with the first coming of Jesus Christ the age to come already dawned, but it is not yet complete; it awaits the Paraousia for its consummation” (136).

The notion of already/not yet allows Pate to interpret some texts in a kind of preterist light, while maintaining that they still have yet to find their fullest realization. An example can be found in the letters to the churches in which Pate notes that these are set against the background of Caesar worship while also pointing forward to future events (139ff).

Pate’s view is decidedly focused on the millennium and a more literal reading of the texts than the previous two views. The interpretation of Christ’s return is illustrative (166ff).

Classical Dispensationalist View

Robert Thomas argues that dispensationalism must be viewed in light of its hermeneutical system, which attempts to remain as literal as possible throughout the itnerpretation of a text (180). Thus, Thomas is an ardent futurist, waiting for the events recorded in Genesis to come about.

A major challenge for this view is the interpretation of texts about Christ coming “soon” and “quickly.” Thomas notes that this theme can be grounded in the notion of imminence in which we are to always be ready for Christ’s return as opposed to a notion of immediacy (189).

A typical classical dispensationalist reading of Revelation can be found in Thomas’ interpretation of the horsemen. He notes that the first “portrays a rider on a white horse, who represents a growing movement of anti-Christian and false Christian forces at work early in the period… the third… rider on a black horse [represents] famine-inducing forces….” (193-194). Thomas also argues that Israel is not the church and so must have the promises fulfilled to Israel as a nation (196ff).

Thomas argues that the major issue is dependent upon which hermeneutical system one employs. If one employs a literal hermeneutic, he contends, one will be dispensational. Period (211-214).

Analysis/Conclusion

I will only briefly comment on each view here.

Preterism

Gentry’s case is quite strong, but I have to wonder about the appeal to the language of “coming soon,” particularly in light of the constant refrain in the Hebrew Scriptures of the day of the Lord being “near.” These prophets clearly did not witness the “day of the Lord” (which, on preterist views is either the 70AD destruction of the Temple or still is yet to come), and so such language has a precedent for longer periods of time than the preterist appeals to.

Overall, however, some of the themes Gentry points to does hint at the possibility for interpreting certain prophecies as fulfilled in the destruction of Jerusalem.

Idealism

The idealist position has some draw for me because it focuses on the applicability of the book to all Christians in every time and place. In particular, the idealist interpretation of the letters to the churches is, I think, spot on. It allows for historicity while also noting the fact that we continue to live in an age in which all those types of churches still exist.

Yet I can’t help but also note that the idealist interpretation at times seems to play too fast and loose with the text, assuming that certain persons or events are types when it seems more clearly to point to a future fulfillment. Of course, the idealist could respond by saying many of these still are in the future after all.

Progressive Dispensationalism

There is great appeal in the notion of the already/not yet aspects of Revelation, which seems to give proper deference to the historical background of the book while also grounding it ultimately in the future promised fulfillment.

It is interesting to see that Pate is willing to interpret some aspects of the text figuratively, yet remains convinced that there will be a literal 1000 year reign, among other things. One could charge him with inconsistency here (as Robert Thomas does).

Classical Dispensationalism

I admit Thomas’ view was the most confusing for me. He insists that one must read the text literally, but then says that the white horse is not a white horse with a rider but rather “anti-Christian and false Christian forces.” Frankly, that is not the literal meaning of the text. It is commendable to desire to stay as true to the text’s meaning as possible, but using the word “literal” in this way seems to be abuse of language.

But Thomas’ view also has more to recommend it, such as his focus upon the future fulfillment. It is hard to read Revelation and not see many of the events as yet to occur, particularly if one desires to read the text as literally as possible.

General remarks

One thing I must note is that I did experience some great disappointment with the book in that it did not follow the standard format of the Zondervan Counterpoints series. Specifically, the book does not have each author interacting with the others after each view. Although the authors clearly had access to the other essays and were given the opportunity to interact via footnotes throughout their own essay, the level of interaction was not on par with other books in the series.

Others have expressed displeasure with the fact that the book does not present the historicist view of Revelation. I share some of that, though I would still maintain that–despite other reviewers [mostly on Amazon] are saying–there are definitely four distinct views presented in this book. They do not cover all the views as comprehensively as some might like, but the views which are included are each unique and worth reading. The quick dismissal of historicism in the introduction may be the consensus of scholarship, but historicism remains a major view among the laity as well as many clergy and some scholars. To have it not included is not the greatest crime, but it does hint at a lack of completeness with the survey here.

Overall, I would recommend this book as a way for those interested in Revelation and eschatology more generally to read. It presents four major views of the interpretation of Revelation by giving each author a rather lengthy section to make their case. Readers will be familiarized with the different views, along with arguments for and against each view. Although the book could be improved by the inclusion of the historicist position and greater interaction between the views, Four Views on the Book of Revelation is a worthy read. Let me know what you think. What is your view on Revelation?

Links

Like this page on Facebook: J.W. Wartick – “Always Have a Reason.”

Book Review: “Understanding End Times Prophecy” by Paul Benware– I review a book on eschatology written from the premillenial dispensationalist position.

Source: Four Views on the Book of Revelation edited by C. Marvin Pate (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1998).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Understanding End Times Prophecy” by Paul Benware

Understanding End Times Prophecy

Understanding End Times Prophecy by Paul Benware certainly deserves its subtitle: “A Comprehensive Approach.” Benware presents a lengthy tome defending his position, dispensational premillenialism (more on that soon), while also outlining and critiquing many other views on various eschatological concepts.

Wait, What?

Yes, I just used the words dispensational premillenialism together in a sentence as though it made sense. It does. That is one of the many views Benware surveys in the book. Before reading Understanding End Times Prophecy (hereafter UEP), I admit I could not have distinguished a dispensational premillenialist from an amillenialist. Nor could I have identified a pre-wrath view in contrast with a post-wrath view. Benware’s book touches all of these and more, explaining the various positions out there on the various eschatological themes while also providing a thorough critique of those with which he disagrees.

Outline of Contents

Benware starts by outlining some principles for interpreting Biblical prophecy. Primary among these is the notion that prophetic passages must be interpreted literally. Benware explains: “Literal interpretation assumes that… [God] based His revelatory communication on the normal rules of human communication. Literal interpretation understands that in normal communication and in the Scriptures figures of speech are valuable as communication devices…” and it is therefore “not… a rigid ‘letterism’ or ‘mechanical understanding of the language’ that ignores symbols and figures” (23-24).

UEP then outlines a broad understanding of Biblical covenants, noting that the covenant God made with Abraham was unconditional, and so must be fulfilled.Next, Benware turns to a number of passages which outline the Palestinian, Davidic, and New Covenants. These he discusses in the context of promises God makes to Israel which must be fulfilled.

The next major section outlines the major views on the millennium. Benware favors the dispensational premillenial view and so spends some time outlining it.The dispensational view focuses on the covenants found throughout the Bible. It holds that there are different “economies” of God’s working. These dispensations are not time periods, nor are they different ways of salvation. Instead, they are specific truths about how God chooses to work with His people (86ff). This view also holds that God will fulfill promises through Israel as a literal nation in the place that God promised them (88ff).

The premillenial view holds that Christ returns before the millennial kingdom. It holds that the millennium is a literal thousand-year reign of Jesus on earth. Thus, there are two resurrections: first, before the millennial kingdom; second, after the millennial kingdom. Israel factors prominently into this view; Israel will be part of the thousand year reign and will occupy the land that God promised unconditionally to Abraham (94ff). Benware argues against the notion that Israel has become displaced or fulfilled in the church (103-120).

Then Benware turns to the view of amillenialism. Essentially, this view holds that the “millennium” is non-literal and is being fulfilled now during the church age. There is one resurrection, and the judgment comes immediately upon Christ’s return. Thus, the current period is the millennial kingdom (121-137).

Postmillenialism is the subject next discussed in UEP. This view tends to be tied into the notion that we are now living in the kingdom of God and so will usher in a golden age through social justice or action. After this undefined point, Christ will return to judge (139ff). Benware is highly critical of this view, noting that it relies upon the notion that we will continue improving the world (yet the world seems to be falling farther rather than progressing); as well as its rejection of the notion of a literal reign of Israel (150ff).

Finally, Benware evaluates preterism. Essentially, this view holds that the events prophesied in Revelation and elsewhere have either all or mostly been fulfilled already. There is much diversity within this perspective, but largely it is tied in with the notion that the destruction of the temple ushered in the end times (154ff).

The next major area of evaluation in UEP is that of the rapture. Benware analyzes pre-tribulation; post-tribulation; and other rapture views. Pre-tribulation is the view that the rapture will happen before the tribulation period. Post-tribulation is the view that the rapture happens after the tribulation. These directly tie into how one views the coming of Christ and the millennial kingdom (207ff).

Finally, UEP ends with outlines of the seventieth week of the book of Daniel, the Kingdom of God, death and the intermediate state, and the final eternal state. An enormous amount of exposition and discussion is tucked into these final chapters. For example, Benware includes a critique of annihilationism.

I have here only touched on the surface of UEP. Benware is exceedingly thorough and has managed to write an amazing resource on the issues related to End Times Prophecy.

Analysis

As has been noted, UEP is a simply fantastic resource for those who want to look at the various views which are discussed in contemporary evangelicalism. Benware has also provided an extremely detailed exposition of the dispensational premillenialist position. If someone wants to critique that view, UEP will be a book which they must reference. It is that good and that comprehensive.

Furthermore, Benware provides a number of excellent insights through the use of charts. Throughout UEP, there are charts scattered which summarize the content of what Benware argues, show pictorially what various views teach, and more. These charts will become handy for readers to reference later when they want to discuss the issues Benware raises. They also help interested readers learn what various views and positions teach.

Benware rightly shatters false notions that Biblical prophecy is some kind of indiscernible mystery language which humans weren’t meant to think on. His care for making clear what the Bible teaches on a number of issues is noteworthy.

Unfortunately, there are several areas in the book which are cause for caution. Benware’s use of proof texts is sometimes questionable. There is great merit to utilizing a series of related texts after an assertion in order to support one’s argument, but upon looking up several texts that Benware cites to make his points, it seems that he often stretched texts far out of their context or even cited texts which had nothing to do with the argument he made in the context in which he cited them. For just one example, Benware writes “The second phase of his [the Antichrist’s] careerwill take place during the first half of the tribulation… During his rise to power he will make enemies who will assassinate him near the midpoint of the tribulation (cf. Rev. 13:3, 12, 14). But much to the astonishment of the world, he is restored to life and becomes the object of worship (along with Satan)” (300). Note that Benware specifically says that the Antichrist will be assassinated and resurrected. Now, turn to the passages that Benware cites. Revelation 13:3, 12, and 14 state:

3: One of the heads of the beast seemed to have had a fatal wound, but the fatal wound had been healed. The whole world was filled with wonder and followed the beast… 12: It exercised all the authority of the first beast on its behalf, and made the earth and its inhabitants worship the first beast, whose fatal wound had been healed… 14: Because of the signs it was given power to perform on behalf of the first beast, it deceived the inhabitants of the earth. It ordered them to set up an image in honor of the beast who was wounded by the sword and yet lived. (NIV)

Now, where in this section does it say the Antichrist will be assassinated? Where in this section does it talk about the Antichrist dying and being raised to life? Strangely, Benware seems to reject the literal hermeneutic he advocates, and begins to interpret texts in ways that bend them to the breaking point.

The issue of these proof texts opens a broader critique of UEP. Benware constantly insists upon a literal reading of Revelation and other prophetic texts, while also criticizing those who hold other views of using an inconsistent hermeneutic. Yet, as I believe I demonstrated above, Benware often goes well beyond the literal meaning of the texts and comes to conclusions which stretch them past literal readings. In fact, it seems that Benware balances an often literalistic reading of the text with a non-literal reading. Thus, Benware seems to fall victim to the very error he accuses all other positions of falling into.

An overall critique of the position Benware holds would take far too much space and time for this reader to dedicate in this review, but I would note that the conclusions Benware comes to are often the result of the combination of literalistic readings and/or taking texts beyond what they say that I noted above. Some of the worrisome issues include the notion that the sacrificial system will be reinstated (334ff); a view in which the notion that the church seems in no way fulfill the Biblical prophecies about Israel (103ff); hyper-anthropomorphism of spiritual beings (i.e. demons, which are spiritual beings, being physically restricted [130]); and the insistence on literalizing all numbers in the Bible (168), among issues. It’s not that Benware doesn’t argue for these points; instead, it was that it seems his method to get his conclusions was sometimes faulty, and the case not infrequently was overstated.

One minor issue is Benware’s use of citations. It’s not that he fails to cite sources; rather, the difficulty is that he inconsistently tells the reader where the source is from. Very often Benware block quotes another text (with proper end note citation) without letting the reader know who or what he is quoting. Although this may be better for readers only interested in the argument, it can be very frustrating for those interested in knowing where Benware is getting his information to have to flip to the back of the book all the time to trace down sources. The problem is compounded by the fact that sometimes he does tell the reader where the quote is from (for example, he’ll write “so-and-so argues [quote]”) while at other times he just dives directly into the quote. The inconsistent application here may be a minor problem, but it did cause major frustration through my reading of the text.

Conclusion

Understanding End Times Prophecy is worthy reading. It provides an extremely in-depth look at the dispensational premillenial position. More importantly, Benware gives readers an overview of every major position on the millenium, the rapture, and the tribulation. The book therefore provides both an excellent starting point for readers interested in exploring eschatological views while also giving readers interested in the specific position of dispensational premillenialism a comprehensive look at that view. It comes recommended, with the caveat of the noted difficulties above. It would be hard to have a better introduction to the issues of Biblical prophecy from a premillennialist perspective than this one. The question remains, however, whether that view is correct. So far as this reader is concerned, that question remains unsettled.

Source

Paul Beware Understanding End Times Prophecy (Chicago: Moody, 2006).

Disclaimer: I was provided a review copy of this book by the publisher My thanks to Moody Books for the opportunity to review the book..

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Review of “Love Wins” by Rob Bell: Preface and Chapter 1

I know I am late to this party. It has taken me a while to get around to reading Love Wins

I know I am late to this party. It has taken me a while to get around to reading Love Wins by Rob Bell. There are many other looks at Love Wins available online, both critical and positive. What do I hope to offer here? I will analyze Rob Bell’s arguments in three primary ways: in light of historical theology, in light of methodology, and in light of analytic theology. I believe this will offer a thorough look at several of Bell’s claims. I hope to offer as even-handed an analysis as possible.

Rob Bell’s argument will be examined for historical accuracy and philosophical rigor. Furthermore, I will examine how Rob Bell makes his argument, because method is often one of the primary ways that people err in their theology. I begin with an analysis of the Preface and Chapter 1. I am hoping to release one post a week as I analyze this text. I will post each section with an outline of the arguments followed by my analysis.

Before I begin, one more note on this analysis: I have not read the book yet. My reason for this is I want to have it fresh in my mind as I do the analysis instead of coming to the text with a preconceived notion of what I remember it saying. Thus, these analyses will be based on a reading of the book chapter by chapter. I will end with an overall review once I wrap up the book. See the end of the post for links to other chapters.

Preface- “Millions of Us”

Outline

Rob Bell begins his book with a fairly simple statement “I believe that Jesus’s story is first and foremost about the love of God for every single one of us” (vii). Bell asserts that “Jesus’s story has been hijacked by a number of other stories… it’s time to reclaim it” (vii-viii). He points out that some teachings about Jesus have caused people to stumble, and that others do not discuss the issue of hell for various reasons.

Analysis

Bell is to be commended for taking on an issue that many are afraid to discuss. It is true that some people and even churches will not delve into the topic of hell. It is important to talk about this doctrine, as it has been part of Christian teaching from the beginning.

Unfortunately, it seems that Bell has already made a methodological mistake. He implored readers to “please understand that nothing in this book hasn’t been taught, suggested, or celebrated by many before me. I haven’t come up with a radical new teaching… That’s the beauty of the historic, orthodox Christian faith. It’s a deep, wide, diverse stream that’s been flowing for thousands of years…” (x-xi).

There are actually two errors here. First, simple diversity on a topic doesn’t somehow automatically validate all positions. Just because there was diversity about the doctrine of the Trinity doesn’t mean that the Arian position is somehow a valid theological perspective. Thus, it seems that Bell’s point here is moot. Diversity does not mean validity.

Second, historic, orthodox faith is not a diverse array of beliefs. The historic Christian faith has been define in universally acknowledged creeds which state what the universal church teaches on various essentials for the Christian faith. In fairness to Bell, he may be using “orthodox” to mean a denominational perspective, wherein the wider spectrum of beliefs is what may be considered “orthodox.”

Chapter 1: “What About the Flat Tire?”

Outline

Bell starts with a story about a quote from Gandhi, which prompted someone to write “Reality check: He’s in hell.” Bell reacts to this with a series of questions: “Really? Gandhi’s in hell? He is? We have confirmation of this? Somebody knows this? Without a doubt?” (1-2). Elsewhere, he focuses in on the individual again, asking whether it is true that the Christian message for someone who claimed to be an atheist during life has “no hope” (3).

He goes on to ask: “Has God created millions of people over tens of thousands of years who are going to spend eternity in anguish? Can God do this, or even allow this, and still claim to be a loving God? Does God punish people for thousands of years with infinite, eternal torment for things they did in their few finite years of life?” (2).

After focusing on the case of an individual’s salvation and whether there is an age of accountability, Bell focuses on the nature of salvation. “[W]hat exactly would have to happen… to change [an individual’s] future? Would he have had to perform a specific rite or ritual? Or take a class? Or be baptized? Or join a church? Or have something happen somewhere in his heart?” (5). Bell notes that some hold that one has to say a sinner’s prayer or pray in a specific way in order to get saved.

Bell continues to contemplate what it is to be saved, and points out that some believe that it is about a “personal relationship” but that that phrase is never used in the Bible. He asks why, if it is so central to salvation, would such a phrase not be in the Bible? (10-11). Bell asks whether “going to heaven is dependent on something I do” and then asks “How is any of that grace?” (11).

Then, Bell looks at various Biblical narratives, including the faith of the centurion, the discourse with Nicodemus, Paul’s conversion, and more, providing a constant stream of questions and noting apparently different things said about faith and salvation (12-18).

Analysis

Bell is right to focus on the notion of one’s personal fate. It is indeed impossible to declare with certainty that a specific person is in hell. It is always possible that God called them to faith in Christ before they died, even at the last moment. We should never say with 100% certainty that someone is in hell.

Bell is also correct to raise doubts about various things that people allegedly need to do in order to “get saved.” His critique of such theologies is again based around questions instead of head-on arguments, but even that is enough to poke holes into works-based theologies.

There seems to be a rather major methodological error in Bell’s analysis of a “personal relationship” with God.” His argument against using this notion to discuss salvation is to say that the phrase is not used in the Bible anywhere. As noted in the outline, he asks a number of very pointed questions regarding this and notes that the phrase isn’t in the Bible. But there are other phrases not used in the Bible which are central issues for Christianity, like “Trinity.” A phrase not appearing in the Bible does not automatically mean it isn’t taught by the Bible. Things can be derived from Biblical teaching without having the exact phrase we use to describe that teaching appear in the Bible. Just to hammer this home, let me point out that the phrase “Love Wins” nowhere appears in the Bible. One using Bell’s methodology here might come to the conclusion that his book is unbiblical.

Just as an aside, I found it a bit of a methodological problem that Bell begins the book with a chapter that is almost entirely questions. He promises answers later, but for now it seems like all the reader is left with is a bunch of–make no mistake about it–leading questions. I think that leading questions are appropriate for teaching, but not so much for defense of a position.

Conclusion

So far, we have seen that Bell makes a few methodological errors, each at a central part of his chapter. First, he made the assumption that diversity of views means validity of all. We have seen that such is not the case, diversity of views does not put them all on a level playing field. Second, he argued that because a phrase isn’t in the Bible, it doesn’t seem to be Biblical. We pointed out that this would collapse Bell’s own work because “love wins” is not found in the Bible. Even if it were, however, we noted that the mere absence of a phrase does not entail its falsehood or unbiblical nature.

However, we have also had several good things to say about Love Wins. In particular, his analysis of works-based systems of salvation was helpful. The fact that Bell is willing to discuss a controversial topic and ask the hard questions is also commendable.

Next week, we’ll analyze Chapter 2, which is about heaven. I look forward to your comments!

Links

Review of “Love Wins” by Rob Bell: Chapter 2– I review chapter 2.

Review of “Love Wins” by Rob Bell: Chapter 3– I look at Chapter 3: Hell.

Review of “Love Wins” by Rob Bell: Chapter 4– I look at Chapter 4: Does God Get what God Wants?

Review of “Love Wins” by Rob Bell: Chapter 5– I analyze chapter 5.

Love Wins Critique– I found this to be a very informative series critiquing the book. For all the posts in the series, check out this post.

Should we condemn Rob Bell?– a pretty excellent response to Bell’s book and whether we should condemn different doctrines. Also check out his video on “Is Love Wins Biblical?”

Source

Rob Bell, Love Wins (New York: HarperCollins, 2011).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

All will be made New: Mayans, end times, and eschatology, oh my!

Is it the end? People are rushing to stores stocking up on bottled water and the necessities, preparing for the latest “end” which our world will endure. We’ve endured a few just this year. Some are now saying that the Mayan Calendar counts down to December 21, 2012 and that this was their prediction of the end of the world. The Mayans were extremely accurate in their calendar, so some people are thinking maybe they knew something we do not.

Is it the end? People are rushing to stores stocking up on bottled water and the necessities, preparing for the latest “end” which our world will endure. We’ve endured a few just this year. Some are now saying that the Mayan Calendar counts down to December 21, 2012 and that this was their prediction of the end of the world. The Mayans were extremely accurate in their calendar, so some people are thinking maybe they knew something we do not.

It just so happens that one of my random interests for quite some time has been ancient Mesoamerican history. I love reading about the Maya, Aztec, Inca, and Olmec cultures. Here, I’ll be drawing on those years of study (I am no expert–please don’t get me wrong here) along with my thoughts on Christian eschatology to provide a discussion of the latest “end of the world.”

The Mayans

Cultural Understanding

People often talk about the Mayan Calendar without placing it in its cultural context. The Ancient Maya were a very advanced people. It is easy to think that the people who inhabited ancient South America were a bunch of paganistic simpletons who knew little of the goings on in the world until a boat of enlightened Europeans showed up and taught them better. Such a view is, of course, extremely Eurocentric, and I would suggest it is also betrays a certain lack of knowledge over what it means to be an advanced civilization. The Maya certainly fill that role well, albeit with different types of advancement.

One could argue that the differences in advancements was due, in part, to the radically different worldviews operating in independent spheres of influence. The values of European cultures were shaped by the Christian worldview, and so their concepts of what was important were very divergent from that of the polytheistic Maya. Indeed, this could account for a number of the extreme differences in practical areas, such as the differences in military technology, and of course in the development of religious doctrine. The Maya were not, as some have argued in the past, necessarily a bunch of noble people. Their artwork portraying their religious ceremonies and conquests makes this explicit, with all kinds of atrocities being glorified through their art. An extended comparison of the development of Western and pre-Columbian societies would be fascinating but it is beyond the realm of my discussion here. My point is that the ancient Maya were a very different people and culture from our own.

Why emphasize this point? Well, for one, because the interpretations which have been given to the Mayan Calendar have largely been using a western view of meaning for calendars, dates, and events to interpret a distinctly non-western culture’s apparatus for interacting with reality. The Mayan Calendar is not some construct in a void to be interpreted by various persons from whatever presuppositional strata in which they operate. No, it must be placed within its cultural context in order to even begin to understand what it means that the calendar should have an end.

The Mayan Calendar

Robert Sharer and Loa Traxler discuss the Mayan Calendar extensively in their monumental work, The Ancient Maya. Their work has just a phenomenal outline of how the calendar worked, but to outline it all would take a lot of room. Here, we’ll focus on two things: The Long Count in the Mayan Calendar and its interpretative framework.

Sharer and Traxler note that:

We take for granted the need to have a fixed point from which to count chronological records, but the ancient Maya seem to have been the only pre-Columbian society to use this basic concept. Different societies select different events as a starting point for their calendars. Our Western chronology, the Gregorian calendar, begins with the traditional year for the birth of Christ. (110, cited below)

The Mayan calendar, on the other hand, uses the end of the last “great cycle” as their starting point for the calendar. They measure something called “The Long Count” which is an extended way to determine a great cycle of 13 “bak’tuns” which are each periods of about 5,128 solar years (110). The previous long count had ended in 3114 BC, and that was the date the Mayans held “established the time of the creation of the current world” (110). And yes, the current “Long Count” will be ending December 21, 2012. What does this mean?

The calendar was not just used for chronology, but rather served more uses, such as divination. Sharer and Traxler note that the calendar was “a source of great power” in the Maya society (102). The Long Count “functioned as an absolute chronology by tracking the number of days elapsed from a zero date to reach a given day recorded by these lesser cycles” (104). Thus, the Long Count served to place the entire calendar cycle into a context: it established a measurable starting point and ending point for their calendar, which was itself extremely accurate due to its use of various astronomical measurements.

The Mayan Calendar shares one distinctive with that of the other Mesoamerican societies, namely, the use of a 52 year cycle. This cycle was celebrated as the end of the world by the Aztecs. The close of one of these 52 year periods literally meant that “the world would come to an end” (107). Yet this end of the world, which happened every 52 years, was not something feared, but rather celebrated due to the dawn of a new Sacred Fire, “the gods had given the world another 52-year lease on life” (107).

We thus have two possible ways to interpret the end of the Mayan Calendar. First, we can see it as simply the terminus of 13 bak’tuns and the end of the unit of measurement of absolute time, which would simply inaugurate the beginning of another cycle of 13 bak’tuns. Second, we can extrapolate from the cultural context that perhaps each terminus of this cycle would be anticipated as the beginning of another “lease on life.” But this is of the utmost importance: neither interpretation suggests some kind of cataclysmic ending of the space-time universe. To call the Mayan Calendar a “prophecy” of endtimes is nothing more than sensationalism. What cause is there to fear this?

Christians know that the end will come. However, this should not be surprising to anyone with knowledge of astronomy and physics. Indeed, our universe is ticking down to a cosmic heat death. Our universe itself will end. The energy will disperse, the stars will burn out, and all that will be left will be hulks of matter strewn about an ever-expanding galaxy. Or, perhaps there will be a “great crunch”–something I admit I am highly skeptical about–which will lead to an explosion of a new universe. But Christians have a unique perspective on the end of the world.

…[C]oncerning that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but the Father only. Matthew 24:36a.

First, no one will know when the end is come. The end is coming, but it will be like a thief in the night. Jesus tells us that it will be like in the days of Noah, where people continued to live their lives despite the impending doom.

Second, the Christian expects God to be the one to usher in this end. The end will be a new creation. Tears will be wiped away (Revelation 21:4) and creation will be restored. Unfortunately, some Christians have taken this to mean the utter annihilation of all things in the spatio-temporal universe. These Christians will sometimes have a dismissive attitude over the stewardship of the earth. After all, they argue, this universe will be utterly destroyed and we will have a perfect one made for us. Why bother conserving resources? This attitude is simply wrong, and as I have noted elsewhere, we are called to care for creation, something which evangelicals who disagree on certain topics unanimously affirm.

As Christians we are called to always be ready for Christ’s triumphant return. But that preparation does not mean being fearful of every end-time “prophecy.” Indeed, Jesus tells us that many will say the end has come but they are false prophets (Matthew 7:15; 24:4-5; 24:10-11; Luke 21:8; Mark 13:21-23). No, the preparation is the call to make disciples of all nations and to care for those in need.

We will endure another “end of the world” on the 21st of this year. Let’s take the time to reflect on what our Lord tells us in His Word. We do not know how or when, but God knows. We do not know the day or the hour, but God knows. God will take care of us. Let us thank Him.

Links

December 22nd, 2012– A poignant comic which speaks to the reality of what will happen on December 22, 2012.