Islam

Is Islam Violent? – A response to a meme

I saw a few friends sharing or commenting on the meme I’ve shared here the other day and thought it was definitely worth a response. Here at the start I want to note that I do not condone the image shared here and think it’s deeply problematic for reasons that will become clear in what follows.

I think that we need to be careful when discussing things like this primarily for two reasons: 1) verses quoted out of context can be used to support anything; for example, I often run into atheists quoting from Joshua and arguing that it means that Christianity is inherently violent or has violent roots; 2) the picture itself doesn’t really do much to make me think any effort was made to understand what is being quoted. See below.

I’m not an expert in Islam, but I have taken a graduate level course on the topic. Moreover, there are some basic problems with this meme. One issue with this picture is that it quotes from “Koran chapter:verse” when the proper term would be “Surah chapter:verse.” Saying “Koran” instead of “Surah” is similar to saying “Bible 12:3:15.” The Qu’ran is one book, so this does not cause distortion of where to find the quotes, but in my reading this method of citation seems not quite proper. [Thanks to several readers for pointing out a need to edit here.]

Another issue is that in the Qu’ran, people aren’t referred to as Muslims but rather believers, etc. Again, this is a fairly basic misunderstanding that would be like putting the word “Christian” into the Bible all over the place when it’s not there.

I took the liberty of looking up a couple of these Surahs. Surah 8:65 is quoted in this picture as “The unbelievers are stupid; urge the Muslims to fight them” in fact says, according to the Sahih international version of the Qu’ran, ” O Prophet, urge the believers to battle. If there are among you twenty [who are] steadfast, they will overcome two hundred. And if there are among you one hundred [who are] steadfast, they will overcome a thousand of those who have disbelieved because they are a people who do not understand.” Not only does this not have the word Muslims, but it is also much longer, and doesn’t call unbelievers stupid. In fact, a comparison of the major English versions show that almost every one says “without understanding” or “do not understand.” The closest it comes to “stupid” is “without intelligence.”

The alleged quotation of 22:19 is particularly problematic, because it completely rips the verse out of context. According to the picture, it says “Punish the unbelievers with garments of fire, hooked iron rods, boiling water, melt their skins and bellies.” Not only is this actually a reference to 22:19-20 but it also is not a command at all. The context of 22:19-20 is the day of judgment and this punishment is that described of for those in hell (see Surah 22:16-17 for more context). Quoting this verse to say Islam is violent would be akin to quoting a passage about weeping and gnashing of teeth from the Bible, turning it into a command to Christians without justification from the text itself and then saying it proves Christianity is violent.

I checked a couple more references and they too not only shortened the alleged “quotes” but also largely took them out of context.

Yet another problem with a picture like this is that it doesn’t account for the fact that in actual practice, the overwhelming majority of Muslims are not violent. I’m not sure of the actual number of Muslims in the U.S. alone, but with over a billion Muslims in the world, if every single one were indeed violent, I would imagine that fighting would be occurring in the streets of Dearborn, MI; New York, Minneapolis, etc. Yet I don’t see this happening. Isolated incidents? Yes. A complete totality of violence everywhere? No. I would argue this is because the vast majority of Muslims have a more nuanced approach to the Qu’ran and its interpretation than simply quoting verses out of context allow; just as Christians would argue for nuanced interpretations in much the same way.

I have not entered into a wider discussion of Islam and religious violence, nor is this the place to do so [see some posts in the links]. I conclude simply by noting that the use of memes like this are, I think, deeply problematic. If we as Christians expect to be treated fairly and have real differences among Christian beliefs and interpretations acknowledged, if we think that people unfairly quote our holy texts out of context and that we deserve to have our nuances of thought also conveyed, then we should do the same for those of other faiths.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

The Myth of “Religion” – Constructing the Other as Enemy– How has the category of “religion” been used to support the premise of religious violence and making the “other” into an enemy?

Book Review: “The Myth of Religious Violence” by William Cavanaugh– Here is a book which discusses the notion of “religious” violence at length with sometimes startling conclusions.

I am not sure who was the original user that put the image up, so I can’t cite it appropriately. I make no claim to owning the image and use it under fair use.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

The Crusades: Wanton Religious Violence?

The Crusades are often cited as the prime example of the evils of religion and of Christianity specifically. The picture is often painted of an innocent world on which Christians came in violent fervor, raping and pillaging as they went. But this picture of the Crusades is inaccurate on a number of levels. Here, I’ll explore the historical context of the Crusades with an eye towards seeing why they occurred. I’ll wrap it up with a discussion on violence and religion.

The Crusades are often cited as the prime example of the evils of religion and of Christianity specifically. The picture is often painted of an innocent world on which Christians came in violent fervor, raping and pillaging as they went. But this picture of the Crusades is inaccurate on a number of levels. Here, I’ll explore the historical context of the Crusades with an eye towards seeing why they occurred. I’ll wrap it up with a discussion on violence and religion.

The Historical Context of the Crusades

The Crusades were not just some bubbling up of violence latent within all religions. Instead, they were part of a history of conquest across the Asian and European continents. Prior to the Crusades, there was a sweeping conquest by the Muslims of territory formerly possessed by various Christian nations.

Muslim invasions had pressed in on all sides. Rodney Stark, in his extremely important work on the Crusades, God’s Battalions, notes the conquests which had pressed in on Europe from all sides. After surveying a number of Muslim conquests, he notes:

Many critics of the Crusades would seem to suppose that after the Muslims had overrun a major portion of Christendom, they should have been ignored or forgiven… This outlook is certainly unrealistic and probably insincere. Not only had the Byzantines lost most of their empire, the enemy was at their gates… (32-33)

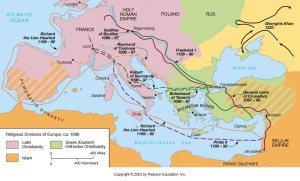

Prior to the Crusades, it is absolutely essential to note that the invaders were, quite literally, at the gates. Constantinople was threatened in the East, and Spain was overthrown in the West. Europe was under assault. The map below illustrates the situation in the time during and before the Crusades well.

The question of the Crusades must be understood within this historical setting: much of the land which European countries had controlled had been taken, by force. Furthermore, those who had taken these lands were knocking on the very gates of Europe, having already crossed into Europe in many places. Stark’s words, therefore, seem to ring true: is it really genuine to assume that these invaders should have been ignored or forgiven? Is that the reality of “secular” nations? It seems to me the very fact that so much land had been lost, as well as so much wealth, would lead many to war for “secular” reasons rather than religious reasons.

Regarding the beginning of the Crusades, Stark writes:

[T]hat’s when it all [The Crusades] started–in the seventh century, when Islamic armies swept over the larger portion of what was then Christian territory: the Middle East, Egypt, and all of North Africa, and then Spain and southern Italy, as well as many major Mediterranean islands including Sicily, Corsica, Cyprus, Rhodes, Crete, Malta, and Sardinia. (9)

So the Crusades were not unprovoked mass murders of innocents. But they were indeed quite brutal, and involved no small amount of very un-Christian activities. Raping and pillaging has no part in the Christian worldview. But Stark once again has a sobering point: war was hell. “[I]t was a brutal and intolerant age” (29). The criticism of brutality equally applies to both sides, but it is also equally anachronistic about the realities of that time. This is not to say that the horrors which occurred were not awful; it is to say that to criticize the Crusaders or Muslims as though they were doing something extraordinarily brutal for their time period is extremely short-sighted.

The Crusades as a Polemic Device

The Crusades were not all-good or all-evil affairs. Like virtually any part of human history, both good and evil intentions and outcomes were involved. To view the Crusades as either an entirely evil affair showing how religion is ultimately prone to violence or as a benevolent attempt by loving people to liberate lands that were rightfully theirs is to grossly oversimplify the historical reality. Unfortunately, modern looks at the Crusades have largely leaned towards the former of these positions, without any acknowledgement of the historical context as noted above.

Instead, the Crusades were a complex of historical events which were often brutal, often provoked, and never motivated for just one reason. To say that the Crusades are a typical example of the violence of religion is, frankly, ahistorical. Was religion involved? Yes. Were there even “religious reasons” involved in the motivations for the Crusades? Clearly. But the general movement with recent attacks on Christianity has been to argue that the Crusades were purely religious instances of religious brutality. The historical perspective provided above provides evidence against that limited perspective.

The Crusades have been used as a kind of polemic device against Christianity. Whenever it is argued that Christianity is reasonable, someone inevitably brings up this historical period. Readers will note that this historical perspective has not attempted to explain away the Crusades. Instead, I have argued for the notion that these events were historically complex, involving a number of factors beyond purely war for the sake of a faith.

As Keith Ward has noted:

It is… beyond dispute that the Crusades were a major disaster… The Crusades can be seen as justified defense… but their conduct and continuance rapidly became unjustifiable on any Christian principles. (68-69, Is Religion Dangerous?

cited below)

The point is simple: there were many motivations behind the Crusades, some of them justified. Yet in carrying out the Crusades, many horrible actions were taken which were unjustifiable. Does this somehow disprove Christianity? Not on Christianity’s own principles, on which we expect to see people acting as sinner-saints in the process of sanctification.

Religious and Secular Violence

Religious and Secular Violence

Apart from the historical outline given here, there is another, equally important point: the dichotomy between religious violence and secular violence is simply a myth. The reason for this is because human actions are far more complex in their motivations than a simple dichotomy of one or the other reason. In our everyday experience, we know that the decisions we make are very rarely made for only one reason.

Oddly, Stark is able to note that “many historians have urged entirely material, secular explanations for the early Muslim conquests…” (13). This, in contrast to the many historians and new atheists who continue to press that the Crusades were entirely religious in their provocations. The unfortunate truth this reveals is the very human tendency to simplify history beyond the point of breaking. Human actions, particularly corporate human actions, have extremely complex motivations behind them. They are not all-or-nothing affairs which happen due to one reason or another. Very often we make decisions for a combination of reasons of differing strengths, weighing options against each other whether we realize it or not.

By utilizing the Crusades as a rhetorical device–a polemic weapon–many have done damage to the historical events themselves. Worse, they have engaged in faulty reasoning and attacked the religious other due to their own emotional hatred. The Crusades were not all-good or all-evil affairs. They were affairs of human history. To forget that is to drown them in a sea of obfuscation. Let us get beyond simple polemical attacks on the “other.” Let us instead engage in honest history and dialogue with our neighbors.

Links

The Myth of “Religion”: Constructing the Other as an enemy– I explore the notion that religion is violent and argue that one of the major difficulties with this notion is that the distinction between secular/religious is a myth.

For an interesting exploration of some aspects of Muslim Philosophy, see my book review: The Closing of the Muslim Mind.

Essential reading: Rodney Stark, God’s Battalions (New York: HarperOne, 2009).

Pacifism, Matthew 5, and “Turning the other cheek”– Glenn Andrew Peoples discusses pacifism in the Christian tradition and some of the arguments in its favor. Ultimately, he finds these arguments wanting.

Sources

Rodney Stark, God’s Battalions (New York: HarperOne, 2009).

Keith Ward, Is Religion Dangerous? (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2006).

Image Credit:

The image of the map is from this page with free resources for instructors. I do not claim credit for this image, nor do I claim that the makers of this resource in any way endorse this post.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “The Closing of the Muslim Mind” by Robert Reilly

One can tell from the outset that Robert Reilly’s The Closing of the Muslim Mind

One can tell from the outset that Robert Reilly’s The Closing of the Muslim Mindwill be highly controversial. The title alone will spark anger and conflict. Yet when one gets to the content of the book, what will be found therein is a thought-provoking discussion about the consequences of particular beliefs.

The central point of the book is “the story of how Islam grappled with the role of reason after its conquests exposed it to Hellenic thought and how the side of reason ultimately lost in the ensuing, deadly struggle” (1). Reilly contrasts this with how the West dealt with some of the same issues: “The radical voluntaraism (God as pure will) and occasionalism (no cause and effect in the natural order) found in them [Muslim theologians in the 9th-12th centuries] were not seen to any significant extent in the West until… David Hume began writing in the eighteenth century. By that time the recognition of reality had become firmly enough established to withstand the assault… Unfortunately, this was not true in Sunni Islam, where these views arrived much earlier” (7).

Reilly maps out the history of the development of Muslim thought. Initially, once Islam came into contact with western philosophy, there was a great amount of interplay (11ff). One early struggle was between man’s free will and fate. This struggle was over the meaning of key verses in the Qur’an as well as a debate over whether the Qur’an is temporal or eternal and uncreated. The notion that the Qur’an is eternal and uncreated, in turn, restricted rationality from evaluating the meaning therein (19).

The development of Muslim reflection on the Qur’an and Allah’s will led to the replacement of reason with rationality (45-46). Similarly, because the Qur’an was Allah’s will, and it did not explicitly endorse kalam (a branch of Muslim philosophy and theology), this rational discourse was to be abandoned (47). Furthermore, this entailed the destruction of the notion of the “autonomy of reason.” Only within the structures of revelation could reason operate effectively (48).

Furthermore, creation itself has no inherent reason. Each moment is merely a “second-to-second manifestation of God’s will” (51). While one may be tempted to say Christianity is exactly like this (and some branches may indeed hold to this teaching), there is an important distinction between the two views, for on the Christian view of God, God’s action is driven by His nature, and so He will operate within His promises as well as within the boundaries He has set for himself. God, on most Christian views, is inherently rational and so will operate in rational ways. So while creation indeed subsists moment-by-moment because of the will of God, God does not arbitrarily change His will (56ff). On the Muslim view, Reilly argues, God’s will is absolute (as opposed to His nature) and so there is absolute voluntarism. At any time, Allah could will that which before Allah did not will (51-53). Furthermore, one cannot say one “knows” God because God is pure will. As pure will, there is no reason for any particular action, and so God is inherently unknowable (54ff).

Another consequence of viewing God as pure will is that good and evil are essentially vacuous terms. “If Allah is pure will, good and evil are only conventions of Allah’s–some things are halal (permitted/lawful) and others are haram (forbidden/unlawful), simply because He says so and for no reasons in themselves” (70). Allah is therefore above morality and the problem of evil is made meaningless, for evil is merely that which God forbids. Essentially, the system is voluntaristic theism (71ff).

Reilly argues that these theological positions have had dire consequences for Islam in the political realm as well. These positions undermine the inherent worth of human beings and posit the primacy of power over reason (128); democracy is the answer to a question the Muslim world has not asked (130), for if God is pure will, then His regents on earth are operating merely under his whims, and can be just as arbitrary in their decisions (131); “Man’s only responsibility is to obey” (131); finally, “there is no ontological foundation for equal human rights in Islam, which formally divides men and women, believer and unbeliever, freeman and slave” (133).

The consequences reach farther, however, and touch the sciences as well. For if Allah’s will is that which causes all things, then to say that there are “natural” explanations is to insult Allah. Instead of saying that hydrogen and oxygen yield water, people are instructed to say “when you bring hydrogen and oxygen together… by the will of Allah water was created…” (142). Of course, the denial of secondary causation touches upon more pragmatic areas of life as well. After all, if Allah wants something to happen, then it will; if not, then it won’t.

Reilly presents a number of contemporary sources demonstrating how these aspects have been radically undermined in the Muslim world, where often anything can pass as a news story and anything can be stated as true (147ff). Furthermore, the Muslim world trends towards underdevelopment and illiteracy. Reilly maintains that some of this is due to the consequences of the theological views outlined above.

Historically, the dilemma within Islam over reason vs. voluntarism came to a head when the Muslim conquests began to be turned back. When defeats happened, Muslims had to ask why it was that they were losing when, presumably, Allah desired them to win (165ff). Some viewed it as a consequence of the stagnation of science and intellectual development in the Muslim world. Others, however, viewed it as a need to go back to the roots of Islam and become even more radical. The world, therefore, according to Reilly, is faced with a crisis: can reason be re-introduced into the Muslim theology and trickle down into every aspect of life, thus freeing the Muslim world from the shackles of voluntarism? Or, will Islam continue down its path and overemphasize the radical occasionalism of nature and God, while undermining reason? Such is the crisis.

It is striking how well Reilly has supported his theses with quotes from the writings of various Muslim theologians and philosophers. Throughout the work, he quotes numerous scholars from both modern and ancient sources. What these quotes reveal is that his points are not found in a vaccuum–rather, the notion that the absolute, determinating, arbitrary will of Allah underlies everything that happens does indeed undermine rationality.

It is interesting here to reflect briefly upon the notion that some of these same themes are found within certain branches of Christianity. Whenever God’s will is placed as the ultimate source of all activity on earth (voluntarism/occasionalism) rather than as a providential will which guides such activity, reason and rationality can be jettisoned just as easily as they were in the development of Muslim thought. Similarly, if Scripture is seen as above any kind of rational inquiry to determine its meaning, one can replace man’s cognitive abilities with blind faith. Reilly’s book can therefore serve as much a warning for Christians engaging in doctrinal reflection as it is a call to Muslims to restore rationality to their faith.

Reilly’s work, The Closing of the Muslim Mind should be seen as required reading for those interested in interfacing with the Muslim faith. Reilly ties together compelling chains of thought which have led to the current Muslim crisis and demonstrates how current thinking is a result of the past. It is a thoroughly researched book and those opposed to his conclusions will be hard-pressed to show the cracks in his theses. I highly recommend this work. Once one gets past the title, which may be seen as inflammatory by some, Reilly presents well-reasoned, compelling, historically grounded argument about how the theology of Islam has led to the destruction of its intellectual capacity.

Robert Reilly, The Closing of the Muslim Mind (Wilmington, Delaware: Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 2010).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.