Uncategorized

James Barr- Inerrancy dominates all other doctrines of the Bible to their detriment

James Barr (1924-2006) was a renowned biblical scholar who, in part, made some of his life’s work pushing back against fundamentalist readings of Scripture and Christianity. I have found his work to be deeply insightful, even reading it 40 or more years after the original publications. His most controversial and perhaps best-known work was Fundamentalism (1977), in which he offered a survey and critique of fundamentalism, which applies incredibly strongly to Evangelicalism and conservative Christianity to this day. I have already written some about this book, and will likely continue to do so as I read more.

Barr notes, in his chapter on the Bible in Fundamentalism, that inerrancy doesn’t actually yield or submit to a “literal reading” of the texts, despite what fundamentalists like to assert. Instead, inerrancy makes all other things about the Bible subordinate to itself. Because inerrancy is of first order importance–it is a doctrine that, for fundamentalists, cannot be abandoned–it cannot be yielded for any reason whatsoever. This includes the attempt by people who hold to inerrancy to read the Bible. They must constantly seek to defend inerrancy above all other things, even changing how the read the Bible in order to keep the doctrine of inerrancy possible in their minds.

Barr writes, “The point of conflict between fundamentalists and others is not over literality but over inerrancy. Even if fundamentalists sometimes say they take the Bible literally, the facts of fundamentalist interpretation show that this is not so. What fundamentalists insist is not that the Bible must be taken literally but that it must be so interpreted as to avoid any admission that it contains any kind of error. In order to avoid imputing error to the Bible, fundamentalists twist and turn back and forward between literal and non-literal interpretation… In order to expound the Bible as thus inerrant, the fundamentalist interpreter varies back and forward between literal and non-literal understandings, indeed he has to do so in order to obtain a Bible that is error-free” (40).

Several examples of this are provided by Barr which were and remain of interest to interpreters today–how to interpret Genesis 1, how to read the ages of Adam, Methuselah, and others, what to do with genealogies, and more. Now, Barr could not and did not anticipate the rise of Young Earth Creationism (YEC) and its attempt to read the Bible literally and continue to ignore or dismiss mountains of scientific evidence against it. But for modern readers, one could point out that even YECs rarely, if ever, read the Bible literally when it tells us about the dome over the Earth or the shape of the Earth and its being flat. Whether it’s God being above the circle of the Earth (Isaiah 40:22) or winds from the four corners of the Earth (Revelation 7:1), YECs do not read these literally, proving Barr’s point about even the most committed literalists oscillating between readings of the text in order to desperately try to preserve inerrancy.

The conclusion is clear: “Inerrancy is maintained only by constantly altering the mode of interpretation, and in particular by abandoning the literal sense as soon as it would be an embarrassment to the view of inerrancy held” (46). Inerrantists can only hold to their position by constantly shifting their interpretive style to suit whatever needs they have in order to maintain inerrancy. This can be seen in many modern debates among inerrantists, such as whether the Gospel authors invented details such as people walking out of their tombs (Matthew 27:53) or if morality itself vitiates against a literal reading of the genocidal commands and actions of Joshua (not to mention the lack of archaeological evidence for this conquest). It is never inerrancy itself that is questioned; rather, the literalists are suddenly non-literal whenever it suits them so as to protect inerrancy.

Obviously inerrantists are aware of this difficulty. Having been a longtime defender of inerrancy myself, and one with a degree and deep interest in apologetics, I had no small series of justifications for why the interpretation changed. It wasn’t the interpretation style changing; it was that different verses or sections of the Bible needed a different approach; some where obviously non-literal. But those that were non-literal just happened to align with whatever challenged the literal reading of the text. Flat earth? The answer- obviously the author is being metaphorical there. Moral challenge from Joshua? The conquest was not genocidal but merely a “normal” conquest with hyperbolic language. &c. &c. forever. But of course, it absolutely was the interpretation style that was changing in these examples, all at the behest of inerrancy, a doctrine that was only invented in answer to modernist questions about the Bible!

I’ll continue writing about Barr’s seminal work, Fundamentalism. I have found it deeply insightful on many points.

SDG.

YHWH and his Asherah? – Biblical Archaeology and Avoiding Dogmatic Conclusions

It is incredibly easy to fall victim to the idea that by reading just a few things on a topic by experts, you are suddenly an expert on the topic–or at least know enough to expertly comment upon it. There have even been studies on this and the eventual name given has been the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Biblical archaeology is absolutely one of those areas in which it is simple to get caught up in that problematical space between expert and one with no knowledge. In part, that’s because archaeology and historical study are such impossibly complex topics that even getting to the details of methodology can be daunting. Reading one take and moving on as if we have the facts is far easier.

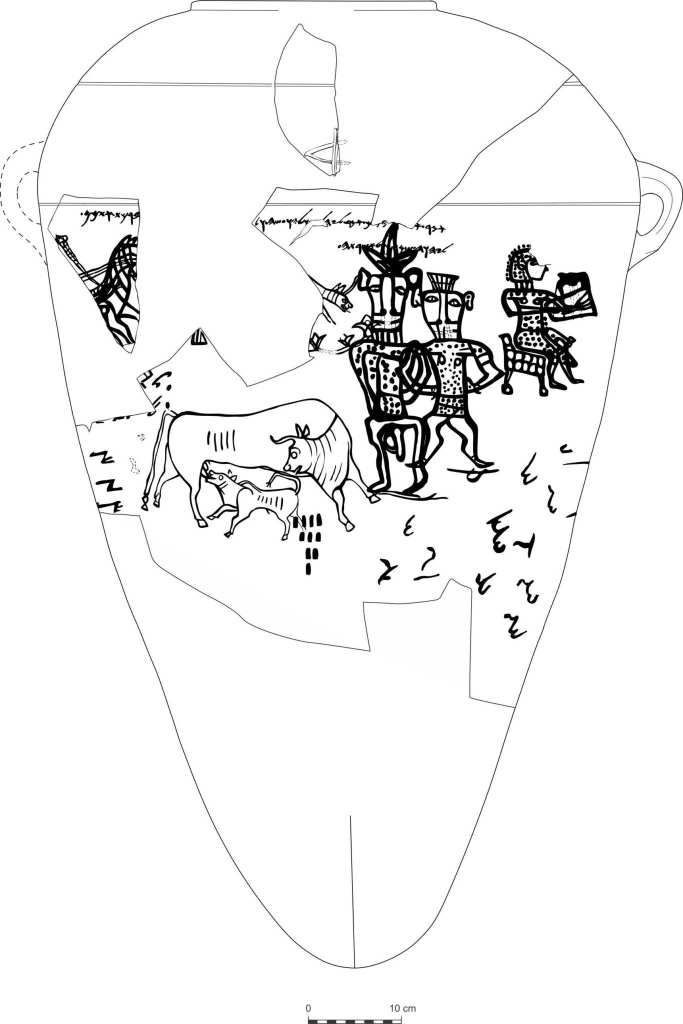

This was recently made clear to me personally when I encountered Theodore J. Lewis’s discussion of inscriptions found at Kuntillet Arjud in his book The Origin and Character of God. There, he notes that some scholars have seen “the female seated lyre player…” as a depiction of Asherah, accompanied by the text “Yahweh of Samaria and his asherah” ((a), 125). However, unlike Dever (discussed below) and others, Lewis notes that this is “inadvisable” because “There is no association of Asherah with music, nor would one expect to find the great mother goddess off center…” and the inscription and imagery likely “come from two separate times.” Additionally, this concept doesn’t account for there being three figures (ibid). Moreover, throughout this section, Lewis notes how difficult it is to parse the difference between asherah as a cultic symbol–an asherah pole or tree that was used in religious practices in Canaan–and citations related to Asherah the goddess, due to them being the same word. Indeed, it is difficult to even fully know whether such a distinction itself is valid.

By contrast, William G. Dever in his Beyond the Texts, cites the same find as depicting “two Bes figures and a half-nude female playing a lyre” ((c), 499). In a note, he argues that the depiction is a reference to Asherah as the goddess, not asherah as a cultic symbol, arguing that despite the missing possessive suffix, it is “graffiti” and so doesn’t need to apply all grammatical rules (ibid, n114, 543). He also argues that reading asherah as a cultic symbol in this inscription (and likely elsewhere) is reflective of “theological presuppositions” rather than the data (ibid).

This may seem a rather obscure fight to be having, but it is not. It would be indicative of at least some aspects of Israelite religion in the region if they saw Asherah as a divine consort of YHWH, something Dever argues elsewhere. However, Lewis does not see this same depiction as evidence of Asherah as YHWH’s consort, and Dever does not here suggest any reason for the third depicted figure (he apparently takes the figure next to the supposed YHWH figure as being Asherah, along with a third seated musician as a different figure).

Not only that, but Dever and Lewis’s approaches are markedly different related to how to treat archaeological and textual data more generally. Dever’s work’s name, Beyond the Texts, hints at his general approach, which he makes explicit therein–elevating archaeological data as perhaps just as significant as textual data. Lewis, however, notes repeatedly the difficulties inherent in using archaeological data to make points beyond the texts. One way this contrast can be seen is Lewis’s suggestion–backed by some scholars cited–that figurines found at archaeological sites should be seen as mortal–not divine–unless the figure being mortal is ruled out by some means (eg. a certain headdress known to be associated with a specific deity, see Lewis, 121ff).

I am by no means an expert in ANE material, archaeology, or historiography. I have studied each, including on master’s level courses, but only obliquely. This was another example that showed me how easy it is to be caught up in expert opinions. I read Dever first and found it utterly convincing, seeing the likelihood that in at least some times and places in ancient Israel, YHWH was likely depicted with a wife. Lewis, a work I’m still in progress of reading, seems to temper that expectation and conclusion somewhat. How do we know which to trust?

I think it is important to realize that as a non-expert, we don’t really need to have a firm opinion on this, in part because we don’t have the knowledge base to even do so. But it is important to be aware of our limitations. Additionally, it is important to realize additional limitations that both Lewis and Dever point out with both archaeology and texts. Archaeology is necessarily limited to what is found by archaeologists, which various studies suggest is an astronomically tiny percentage of all the material that might exist to be excavated. Additionally, the material that survives–even that not yet excavated, is only a tiny percentage of all the material of a culture. Not only were things reused and repurposed, but they were also destroyed, often intentionally. Thus, we are seeing only tiny parts of the true material culture of the ancient past. This applies to texts as well. There are untold numbers of texts forever lost to time that could give any number of clarification on so many fascinating topics. We should be thankful for what we can find, but realize that caution regarding conclusions is deeply important.

Regarding YHWH and Asherah–I don’t know. I think that some of this relies upon religious presuppositions, and I’m including Dever in on that. But I also think that there seems to be enough scattered evidence to suggest that there is some connection between the two. I’ll be interested to read the rest of Lewis’s book and see what he argues with the rest of the material about Asherah and asherah poles. For my readers here, I hope this can serve as a cautionary tale to be aware of how little we know, especially as non-experts.

That said, two things that are extremely clear are that: 1. the Biblical material itself shows evidence of religious development in Israel, and this can be extracted and shown alongside archaeological evidence; ancient Israel did not have a monolithic, exclusively monotheistic religion, though it seems the elites may have developed that and enforced it eventually; 2. there is so much more to the religion(s) of ancient Israel and the region that we have to learn, and certainly far more than the simplistic stories that we tend to learn in church. That doesn’t mean those simplistic stories are to be utterly rejected or seen as misleading or intentionally untrue; merely that there is, as almost always, more complexity than what we learned on a surface level.

Sources

(a) Lewis, Theodore J., The Origin and Character of God: Ancient Israelite Religion through the Lens of Divinity (New York, 2020: Oxford).

(b) Choi, G. (2016). “The Samarian Syncretic Yahwism and the Religious Center of Kuntillet ʿAjrud”. In Ganor, Saar; Kreimerman, Igor; Streit, Katharina; Mumcuoglu, Madeleine (eds.). From Shaʿar Hagolan to Shaaraim: Essays in Honor of Prof. Yosef Garfinkel. Israel Exploration Society.

Dever, William G., Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah (Atlanta, 2017: SBL).

SDG.

Book Review: “Migrations of the Holy: God, State, and the Political Meaning of the Church” by William T. Cavanaugh

It would be difficult for me to understate how much reading William T. Cavanaugh’s book, The Myth of Religious Violence, changed my perspective and set me on paths exploring my faith and its relations with the world. Now, re-reading Migrations of the Holy: God, State, and the Political Meaning of the Church, once again has my head spinning and my thoughts going. Cavanaugh challenges readers to see that “religion” has never left in the west, but our religious fervor has instead been migrated to a new object of worship: the nation state.

Cavanaugh’s work here was written before the recent rise of Christian Nationalism, and it feels utterly prescient in so many ways. But beyond feeling predictive, it also provides warnings and evaluative principles to see how Christians–and other religious persons–in the so-called “West” have preserved deeply religious, deeply committed lifestyles but have simply moved their loyalty from radical loyalty to God-and-other to radical loyalty to the nation state. This can be seen in any number of ways, whether through the veneration of the flag of one’s favored nation state, complete with elaborate ceremonies for the exactly right and proper way to fold the flag to the way people are honored for their “service” to the nation state in the military and other endeavors.

The language used by Cavanaugh helps frame the narrative. He also uses quotes and interlocutors effectively. One example of the latter is the framing of the first chapter, entitled “Killing for the Telephone Company.” The comparison to killing in the name of the nation state and killing for the telephone company creates a radical juxtaposition that shows how absurd it seems to do the former, just as it is the case in the latter.

Cavanaugh’s argument builds on itself. An early assertion that “the state is not a product of society, but creates society” (18) is backed by a number of quotes and commentators from Hobbes to modern political theorists. The migration of the holy from so-called “religious” realms to the supposedly secular nation state is traced along a number of lines. One example draws all the way back on Augustine, who argued that coercive government is a [necessary-ish in his argument] result of the Fall (61). The movement of holy from church to state also creates a crisis for the church, which could lead to a kind of separation from the state even as the state continues to assert sovereignty over all aspects of life.

One later chapter offers a “Christian theological critique of American Exceptionalism” (88ff). Here, we find Cavanaugh fully in his element: “[W]hen a direct, unmediated relationship is posited between America and a transcendent reality, either God or freedom, there is a danger that the state will be divinized” (89). The conceptual nature of “freedom” as highest ideal and seeing America along theological notions of the doctrine of election create a dangerous situation in which the nation state is the object of veneration even as it functions as the arbiter of truth through violence projected internationally. “We [Americans] know what is good for everyone and we have the power to enforce that vision anywhere in the world” (95). This was seen in the time of the publishing of the book (2011) in the continuation of the occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan and can be seen into today with American power being projected internationally for the sake of tenuous and rarely-defined ideals of freedom.

Part of the migration of holy from church to state is the same myth of religious violence Cavanaugh wrote of in his book of that title. By democratizing violence; by moving it directly and exclusively into the sphere of the nation state, we have created dichotomies that are enforced systematically through “us in the West and them, the less enlightened peoples of the world” (111). Violent conflict is reframed in a narrative of cosmic rightness and wrongness, again showing the concept of holiness and judgment as the purview of the nation state (ibid and following). One example of this is “The recent debate over the use and justification of torture by the U.S. government… On the one hand, we claim that we do not torture; on the other hand, we imply that we must” (112). Violence is only accepted in the hands of the nation state and for the sake of whatever ends that nation state has framed as righteous: freedom and liberty, for example.

Cavanaugh puts the reality of holiness as nation state even more starkly when it comes to the use of violence: “It is clear that, among those who identify themselves as Christians in the United States and other countries, there are very few who would be willing to kill in the name of the Christian God, whereas the willingness, under certain circumstances, to kill and die for the nation in war is generally taken for granted” (119). This, of course, is not intended to suggest that violence should be done in the name of the Christian God. The point is, instead, to show that violence itself as showing dedication is wholly in the realm of the sovereign state now. Cavanaugh reinforces this in writing on the Eucharist as God sacrificing God’s self for us, an entirely foreign concept to that of loyalty to the nation state (121-122). From here, Cavanaugh moves into a kind of political theory for the church, among other things.

Honestly, reviewing a book like this almost feels wrong to me. Both of these works by Cavanaugh have had such a massive impact on how I think about things that I worry I cannot convey that adequately in a simple book review. How many superlatives are too many? How much praise is too much? I don’t know. But suffice to say that I believe Migrations of the Holy is a paradigm-shifting book. I hope you’ll read it.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Universalism and Lutheran Anti-Rationalism: A way forward?

I’ve written already on The Foolishness of God: The Place of Reason in the Theology of Martin Luther. I found quite a bit of stimulating discussion within it. Here, I want to focus on the concept of grace and election in Lutheranism and essentially turn Becker’s argument around to see whether it could be used to argue for universalism rather than to simply punt the question of why some are not saved.

The Lutheran Positions on Humanity and God’s Will

There’s a section of the book called simply, “Antirationalism in the Lutheran Doctrine of Conversion.” Here, Becker argues that Lutherans should believe definitionally in humans being completely dead in spiritual things to the point where Lutherans could be seen as basically affirming total depravity. To this end, Becker quotes the Formula of Concord, directly from the Lutheran Confessions:

“[I]n spiritual and divine things the intellect, heart, and will of the unregenerate… are utterly unable, by their own natural powers to understand, believe, accept, think, will, begin, effect, do, work, or concur in working anything… there is not the least spark of spiritual power remaining… by which… [people] can accept offered grace…” (quoted in Becker, 201). On these points, Lutheranism appears to be Calvinism when it comes to the total inability of humankind to respond to, prepare for, or in any other way be credited for any aspect of saving faith.

Alongside this, however, Lutherans also, if they remain convinced by the Lutheran Confessions, “emphatically defend… the universal will of grace… It would be almost unthinkable that [anyone] call [themselves] a Lutheran and not accept the doctrines of universal atonement, universal reconciliation, and universal grace” (203). Despite this, Becker flatly states that all Lutherans and all evangelical Christians reject universalism. There’s no reason given for this rejection[note 1, below]. Thus, Becker’s position is left an unenviable question: why are some saved and not others? Indeed, this was a question I asked quite a bit as I was attempting to work out where I thought I stood on a number of theological questions, oscillating through a number of positions while still being amenable to the Lutheran one.

Becker’s Answer

Becker first outlines the situation in a series of simple charts contrasting numbers denoting how much God wills one to be saved vs. humanity’s resistence to salvation. Calvinism has 100 for humans resisting with 110 for God’s willing some and 90 for God’s willing others, resulting in some humans being saved (110) or not (90) depending on God’s will. Arminianism’s example has God’s willing 100, with human resistance being 90 for some and 110 for others, resulting in some humans being saved (90 resistance) and some not (110). “True Lutheranism” (Becker’s words) has both sides at 100.

So if God’s will and human resistance are at exacting odds, what explains salvation? For Becker, the “real Lutheran” answer is basically ‘we have no idea.’ He writes:

“Synergism, the doctrine that [humans] cooperate, even if only in the lightest degree… in conversion, was Melanchthon’s solution to this difficulty, and most modern Lutherans follow his lead[note 2]. But true historic Lutheranism holds that synergism is ‘the answer of reason.’ Yet true Lutheranism just as vehemently rejects every proposition which would establish either a ‘special grace’ or an ‘irresistable grace’ for the elect. In doing so, it finds itself in a rationally impossible dilemma.

“Because it is convinced that this is the teaching of Scripture, which does not explain the mystery, Lutheranism has simply resolved not to explain it either” (205).

Lutherans are generally inclined to appeal to mystery when there are things unexplainable within theology or doctrine, and I am not really opposed to that. Indeed, there is great appeal there. To assume we can know the intricacies of everything about God, assuming God exists and is infinite, is absurd on its face. So when we see things that are possibly contradictory but seem like they ought to be held, I do not really balk at holding them in tension and acknowledging the mystery of the same. So I do not fault Becker for this appeal. If one holds that the premises of Lutheranism are true AND that some are not saved, then appeal to holding these doctrines in tension and assuming they’re all true but that the way they are true is a mystery to humans isn’t, in my opinion, an invalid move. While I know Lutherans are not infrequently the butt of jokes for their appeals to mystery, I personally think this is both a more honest move and a better move than attempting to fully explain the intricacies of God’s workings. However, I also think that Becker’s imagination is limited by his theological precommitments here.

Lutheran Antirationalism Applied in Defense of Universal Salvation

Here’s the rub: could one not use Becker’s view of Luther’s anti-rationalism when it comes to theology and judging the Bible in order to support rather than reject universalism? Consider again the issue at hand: according to Lutheran theology [and using Becker’s arbitrary numbers], human nature is fallen and resisting God and turning away from salvation at 100 strength. Meanwhile, God wills all humans to be saved and even provided for that salvation, also at 100 strength. But why say that God’s will is only at 100 strength, why not also 110, outweighing the resistance? Lutheran theology, according to Becker, already includes the notion that God absolutely wills all people to be saved. So why doesn’t God get what God wants? As the infinitely powerful creator of the universe, doesn’t it seem odd that God would will all people to be saved and even provide the means by which they will be saved, and yet some are not saved?

Becker’s answer is the appeal to mystery–we just don’t know, and we simply hold in tension the apparently contradictory concepts in a kind of both-and relationship. But couldn’t we simply flip the script? The anti-rationalism involved here, then, is not in punting to mystery to explain why some are saved and not others. Instead, it is in appealing to antirationalism (or mystery) to explain why there are some passages that seem to suggest that some people are lost despite God’s universal salvific will and universal atonement through the Cross.[3] So on this view, instead of juxtaposing “God wills all are saved” and “Some are not saved” and holding those two premises in tension with each other, we are juxtaposing the propositions: “God wills all to be saved” and “There are some teachings in the Bible that appear to say some are not saved.” One can fully affirm that those passages teach Hell[4] and even that they teach it as a place populated eternally. But the tension here is the both and that we affirm that teaching even while affirming that God’s will for all to be saved actually comes to fruition. How is that possible? It’s a mystery, but, as Siegbert writes, “Because it is convinced that this is the teaching of Scripture, which does not explain the mystery, Lutheranism has simply resolved not to explain it either” (205).

Not So Hasty

There are a few counter-arguments here I’d like to briefly acknowledge. The first is the charge that universalism here is being presented in the Lutheran context, and it is essentially a rationalist answer to a question that Scripture doesn’t answer. That is, speaking along the same lines as Becker/Luther, Scripture does teach that God wants all to be saved and even provided for that salvation, but to insist upon actually affirming all are saved is a rationalist conclusion, using human reason to trump other Scriptural teaching [eg. on hell] or to go beyond the clear teaching of Scripture. In reply, it seems clear that the antirationalist Lutheran who attempts to affirm that some end up in hell is stuck with a very similar problem. After all, the only reason they are rejecting universalism, which does have clear passages teaching it in Scripture[5], is because they are reasoning and choosing to affirm some end up in hell as a stronger teaching of Scripture than that of universalism. Indeed, these non-universalists are reasoning that instead of teaching universalism, these passages only teach that God wants all people to be saved and has provided for that salvation. This is just as much a use of reason over Scripture as the contrary. Indeed, how does one really get out of choosing one of the options, with each being taught in Scripture? And since Becker himself admits that the Lutheran position is that God wills and has provided for all to be saved, why not embrace the absurdity of simply admitting that “therefore all are indeed saved, despite some apparent contradictory evidence”?

The second line of counter-argument is that my argument above is an unjustified use of the Lutheran position. Very often Lutheranism holds to both-and statements where Calvinist, Baptist, or other theology picks either-or. One clear example is that of Christ’s real presence in the Lord’s Supper. Whereas Calvinism and Baptist theology each insist upon an either present and detectable or not present and symbolic, Lutheranism teaches that Christ both is present and yet the bread and wine still remain. How is this true? Because Christ made the promise to be present there, and God breaks no promises. And how is that true when we cannot detect that presence? Because God said so. So for this counter-argument against universalism, the both-and is that both God wants all to be saved and yet some are not saved. However, there is nothing in Becker’s argument, nor in any specifically Lutheran position on this that I’m aware of, that suggests we cannot instead shift the both-and to is is true both that all are saved and God’s will succeeds and that Scripture teaches some are lost. How does this work? Because God’s will always succeeds and God’s promises to those who have had salvation provided for them (by Becker’s own admission, this means everyone) will not be broken.[6]

Obvious Other Possibility

Despite strong modern links between conservative Lutheranism and the modern doctrine of inerrancy, one obvious possibility within Lutheranism regarding universalism is to simply deny inerrancy and affirm a strong view of Scripture that isn’t bogged down by the modern invention of that doctrine. This has clear and repeated historic precedent in Lutheran theology, whether it was the questioning of books as canonical (including James and Revelation) by Luther and Lutherans early on or into later Reformers or even theologians like Dietrich Bonhoeffer or any number of German and American [and presumably elsewhere, though I’m not familiar enough to say so] Lutherans into today. For these Lutherans, one can simply accept the teaching that Becker strongly affirms just is basic Lutheranism: that God wants all to be saved and has provided the means for them to be saved and affirm universalism to basically make a set of non-contradictory doctrinal beliefs. In this case, the supposed clear teachings of Scripture that some are condemned to hell are simply mistaken or perhaps misinformed.

There is some obvious appeal to this strategy. For one, it eliminates the need to take an anti-rationalist or, minimally, a mysterian approach to affirm seemingly contradictory doctrines. For another, it eliminates the difficulty of trying to affirm teachings on hell that seem to be blatantly against God’s will in other passages. However, embracing an anti-inerrancy in Lutheranism simply to affirm universalism would clearly be a rationalist approach to the problem and perhaps then fall victim to the arguments to that effect. On the flip side, if Lutherans wish to simply follow what has long been the position of Lutherans throughout time–that of affirming the Bible as the authority on doctrinal teaching without rising the Bible up to the position of being on par with God as inerrancy does–this charge will not stick.

Whatever the case may be on this, even if it is mistaken, the anti-rationalist Lutheran defense of universalism seems possible.

A Final, Different Anti-Rationalist Defense

Adapting Becker’s nomenclature, he proposes {God 100% wills all humans are saved <=> Humans 100% resist being saved} as the Lutheran position. Thus, the question remains: how/why are some saved and not others?

However, it seems we could easily introduce a third part of this equation: {God 100% wills all humans are saved <=> Humans 100% resist being saved <=> all are saved}. Thus the question is “how are all saved?” and the answer is the same appeal to mystery Becker offers for his equation above. Really the only counter to this from the Lutheran perspective seems to be that you need to include a fourth part of the equation: {God 100% wills all humans are saved <=> Humans 100% resist being saved <=> all are saved <=> some are not saved}. This, however, would mean the Lutheran who is against universalism must defend the fourth term: that some are not saved. And since we both cannot know the mind of God and since Lutheranism is generally very keen to avoid making specific claims about the eternal ends of people and since Lutheranism allows for anti-rationalism in soteriology, at least according to Siegbert, this presents an enormous problem. Because even if the fourth term is defensible on a Lutheran view (and I genuinely believe any such defense would likely skew towards Calvinism or Arminianism instead of Lutheranism), one could simply affirm them all and say the blatantly contradictory terms are true and that we just don’t know how or why. And perhaps that means one affirms merely a “soft” or “hopeful” universalism, but it seems obvious that it could not entirely exclude universalism from the equation.

Conclusion

It seems to me that Becker’s explanation of salvation from a Lutheran perspectie is fairly accurate, but lacks theological imagination. For whatever reason, Becker has simply limited his perspective on what options are available for Lutherans to answer the question of why are some saved and not others. One possible answer is simply: all are saved. I should note I’m not claiming this is a distinctively Lutheran answer, nor am I claiming it is one that has deep roots in the Lutheran tradition. My main and basically only claim is that universalism simply is a possibility on Lutheran theology, and that supposed anti-rationalism when it comes to things like soteriology in Lutheranism can be applied to support it.

More interestingly, though, is the fact that it seems Lutheranism lends itself to this support. Is it possible that Lutheranism can be uniquely suited to affirm universalism, even for those who want to maintain affirmation of doctrines like inerrancy or of hell? It certainly seems so. The richness of Lutheran tradition is filled with both-ands. Here, we might affirm both that God desires all to be saves and that God succeeds at doing so.

Notes

[1] I suspect it is some sort of latent and inaccurate understanding of church history as seeing universalism as heretical despite it being affirmed by some of the most orthodox names in early Christianity (people like Gregory of Nyssa). There are a number of studies on universalism in Christian theology that demonstrate it was perhaps the majority position of the earliest church, and that multiple strands of Christianity preserved or reaffirmed the doctrine throughout history with little allegedly heretical fallout accompanying it.

[2] I’m quite curious about this side comment about “most modern Lutherans” following the lead of Melanchthon here. While Melanchthon is vehemently condemned in a lot of conservative Lutheran circles for a number of reasons, there are very few Lutherans I’m aware of who would appeal to synergism for… anything. And I’m being inclusive of conservative through progressive Lutherans here. If one claims to be Lutheran, synergism is typically out. I admit to not being knowledgeable enough of Melanchthon himself to know if he claimed synergism. Anyway, to me this claim of Siegbert’s needed quite the citation, and has nothing to back it up. Of course, he was also writing in a different time period (the book was published originally in 1982), so maybe whatever context he was in made it feel a reasonable statement to make.

[3] And this is, of course, assuming that we are reading those passages correctly. One universalist method of interpreting those passages is to see them as warning passages–calling on the Law to provoke people toward God or Godly living. I am not personally convinced of this, though I see it as a possible valid move.

[4] And here one could even affirm some kind of eternal conscious torment as the actual teaching of Scripture, despite much, much evidence to the contrary. Here, tipping my hand, it seems a much more likely reading of these passages is annihilationism or “conditional immortality” rather than eternal conscious punishment. It’s not my purpose here to argue for this, however, as it is not relevant to the point at hand. Instead, I’d direct readers towards arguments making the exegetical case for that position, such as Edward Fudge’s The Fire that Consumes.

[5] Romans 14:11 cf. Isaiah 45:23. In the latter, YHWH is speaking and swears that every knee will bow to YHWH. There are no exclusions. In the Romans passage this text is glossed with the same implication.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “When God Became White” by Grace Ji-Sun Kim

When God Became White by Grace Ji-Sun Kim shows the development of how Western Christianity shaped the narrative of God along lines that became more patriarchal and, ultimately, racist, than it had been.

I find it a little difficult to review this book. On the one hand, it provides quite a bit of stories and short, pithy points that will help readers looking for an introduction to these topics to come to a better understanding of how we got to where we are, particularly in the United States, with a white male patriarchal Christianity. On the other hand, as I read the book, I longed for deeper exploration of some of the topics.

For example, the book makes great points about mission work and how the whiteness of missionaries impacted perception of Christianity and race worldwide (61ff, see in particular 68 and following). Similarly, the author touches upon the fact that race is a humanly invented concept that relies upon social distinctions and contrast and that has historically been defined and redefined (27ff). But, while the latter points are utterly essential to the central thesis of the book–that whiteness has negatively thwarted Christianity in a number of ways–these historical impacts aren’t tied into the greater point, leaving the reader at times with the assumption that with the spread of Christianity came the spread of the concept of whiteness. But this goes against the very brief historical outline presented in the book and also against deeper studies like The History of White People. For me, it seems the thesis would be greatly strengthened with deeper exploration of the developing definition of whiteness and its moving goal posts alongside the differing depictions of Jesus and God and how these two interrelate. As it stands, the interrelationship is assumed, not argued for, and from that assumption comes many of the other theses of the book. And while I’m deeply sympathetic to these theses and the central concepts of the book, it felt like it needed a stronger backbone to link the concept of whiteness to Christianity, especially in light of the acknowledged historical development of that concept.

Much of the argument in the book relies, in fact, upon anecdotes. These are great for illustrative purposes (such as the famous portraits of white Jesus found ubiquitously in churches and grandparents’ foyers) to show the impact of white Jesus on our faith lives, but it doesn’t do as much to show how we can dismantle this or what historically happened to get from the Ancient Near Eastern God/Jesus to what we have today. Is it possible I was hoping for a different book than the one I got? Yes, that’s probably at least part of it. I wanted more depth. As it stands, though, this book does introduce readers to a number of important topics and difficulties with Christianity and the way it has changed into a white gendered God.

When God Became White is a pithy read that makes a number of great points. It doesn’t go deeply into some of the points contained, and relies maybe a bit too much on anecdote, but it remains a read well worth the time to struggle with the points it makes.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “All God’s Children: How Confronting Buried History Can Build Racial Solidarity” by Terence Lester

All God’s Children seeks to help heal racial division by reawakening a knowledge of Black history in its readers.

The way we tell stories matters, and when history is excised or whitewashed, that can create a new narrative that prevents racial justice from happening. Terence Lester confronts this directly, not only noting how everyone has a history (43-45) but also how the way we shape and re-shape narratives can have real world impacts. For example, when people refuse to see parts of history that may be unflattering, that can create divides between groups of people and make it more difficult to find reconciliation (53ff).

Alongside the discussions of history and reconciliation, Lester notes that God has called us to justice. Helpful charts and discussions of solidarity and how to build reconciliation into daily life are offered (eg. 74-75). Part of this includes an understanding that some history was taught through lies and distortions. It is not “erasing history” to bring forth real, firsthand accounts of history that show that much of what was learned is incorrect (92-102). Lester also moves the story forward into how we can engage in our own background and diversity in order to foster communities that bring about change.

All God’s Children provides a much needed way forward in figuring out how to read and contemplate history in the context of racial solidarity. Highly recommended.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “The Wonders of Creation: Learning Stewardship from Narnia and Middle-Earth” by Kristen Page et al.

Both The Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings are cemented into our cultural background. Even people who have never read them or seen any of the movies tend to at least know some of the basics of what each involves. Kristen Page, in The Wonders of Creation: Learning Stewardship from Narnia and Middle-Earth digs more deeply into each of these worlds in order to see how that wondrous landscape could inform our own concept of creation care.

The book is divided into three lectures with responses from various contributors. The first section is about finding insights into the real world in fictional landscapes. The second lecture is about responding to creation’s groaning and applying some of these insights into the real world. The third lecture is about renewal of wonder in regards to creation.

Fans of both Narnia and Middle Earth will be delighted to see these worlds explored with an eye towards the real world. Some of these reflections can be delightful, while others can be severe. For example, the question about the Clean Air act and how the U.S. stopped enforcing it for the sake of the economy set alongside the wonder of Edmund on the stirring of spring in Narnia is a stirring juxtaposition (50-52). Particularly lovely is the call to reinvigorate a love of creation and nature, found both in these fantastical worlds and in rediscovering myth and wonder for ourselves as adults (see, for example, the discussion on page 89 in which the enjoyment of landscapes stirs wonder in a childlike, Narnian way).

The Wonders of Creation is an exciting delve into two beloved fantasy worlds, applying the insights from the richness of each of their authors to our modern situation. I recommend it.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Ending Human Trafficking: A Handbook of Strategies for the Church Today” by Moore, Morgan, and Yim

Human trafficking is a global issue, but one that is difficult to understand without researching the topic. Ending Human Trafficking by Shayne Moore, Sandra Morgan, and Kimberly McOwen Yim seeks to provide individuals and especially churches with resources to understand this awful practice and to help thwart it.

After an introductory chapter, the authors dive into a history of human trafficking as well as groundwork-laying for understanding it today. One of the most important takeaways from these early chapters is that human trafficking probably doesn’t look like you might expect it. People can be living what seems like entirely normal lives on the outside while being trafficked–sometimes even without really knowing it themselves. This makes the topic incredibly complex and also makes it that much more important to dedicate time towards understanding it.

Much of the rest of the book is dedicated toward the goal of integrating understanding and advocacy related to human trafficking. Prevention, protection, prosecution, partnership, policy, and prayer are all aspects that individuals and churches can work towards related to the topic. Identifying risk factors for trafficking is an important task, but the authors also work towards prevention as a goal. The authors also identify and discuss several myths related to trafficking (such as the belief that people who are trafficked are necessarily immigrants). The book as a whole then provides a broad perspective on human trafficking and how to not just understand but also work against it.

Ending Human Trafficking is a necessary and important book that will help people work against this global plague. Recommended for church and individual libraries, but, more importantly, for actually taking action on.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“Women Pastors?” edited by Matthew C. Harrison and John T. Pless -a critical review Hub

I grew up as a member of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, a church body which rejects the ordination of women to the role of pastor. The publishing branch of that denomination, Concordia Publishing House, put out a book entitled Women Pastors? The Ordination of Women in Biblical Lutheran Perspective edited by Matthew C. Harrison (who is the current President of the LCMS) and John T. Pless. I have decided to do a critical review of the book, chapter-by-chapter, for two reasons. 1) I am frequently asked why I support women pastors by friends, family, and people online who do not share my position, and I hope to show that the best arguments my former denomination can bring forward against women pastors fail. 2) I believe the position of the LCMS and other groups like it is deeply mistaken on this, and so it warrants interaction to show that they are wrong. I will, as I said, be tackling this book chapter-by-chapter, sometimes dividing chapters into multiple posts.

Finally, I should note I am reviewing the first edition published in 2008. I have been informed that at least some changes were made shortly thereafter, including in particular the section on the Trinity which is, in the edition I own, disturbingly mistaken. I will continue with the edition I have at hand because, frankly, I don’t have a lot of money to use to get another edition. I’m aware the picture I used is for the third edition.

Chapter and Section Reviews

“The New Testament and the Ordination of Women” by Henry P. Hamann (Part 1)- I respond to the first part of Hamann’s chapter, in which he argues the NT gives no support at all for women pastors, provides a definition of ordination that no one in the NT meets, and then claims women aren’t given ordination in the NT.

“The New Testament and the Ordination of Women” by Henry P. Hamann (Part 2)– The second part of Hamann’s chapter attempts to show commands allegedly prohibiting women from being pastors are not arbitrary.

“Didaskolos” by Bertil Gärtner, Part 1– Gärtner attempts to leverage a broad swathe of Scripture to show that women cannot be pastors. However, his criteria, if pushed to their logical conclusions, would also exclude many the LCMS ordains.

“Didaskolos” by Bertil Gärtner, Part 2– Gärtner appeals to the order of creation to exclude women from ministry and also offers a self-contradictory argument against women pastors.

“1 Corinthians 14:33B-38, 1 Timothy 2:11-14, and the Ordination of Women” by Peter Kriewaldt and Geelong North, Part 1– Kriewaldt and North start with 1 Corinthians 14 to try to show how it absolutely restricts women from the ministry. Textual integrity issues are among the topics raised.

“1 Corinthians 14:33B-38, 1 Timothy 2:11-14, and the Ordination of Women” by Peter Kriewaldt and Geelong North, Part 2– the authors strangely leave off verse 15 of 1 Timothy 2, but that’s just one of the many issues with their interpretation here.

“‘As In All the Churches of the Saints’: A Text-Critical Study of 1 Corinthians 14:34, 35” by David W. Bryce– Bryce’s chapter, attempting to show the textual integrity of the 1 Corinthians passage, makes some mistakes and is also directly contradictory to the previous chapter’s assertion about the textual integrity of the same passage.

“Ordained Proclaimers or Quiet Learners? Women in Worship in Light of 1 Timothy 2” by Charles A. Gieschen– Gieschen’s selective reading of the text purports to show that the words to take literally are just those he takes literally, while those with deeper meanings are just those he needs to do so in order to hold his theological positions.

“The Ordination of Women: A Twentieth-Century Gnostic Heresy?” by Louis A. Brighton– Brighton follows the rule of “everything I disagree with is Gnosticism” when it comes to theology, apparently. The chapter is a practice in forcing your theological opponents to look like that which you think is the worst.

“Section II: Historical Studies” in “Women Pastors?” edited by Matthew C. Harrison and John T. Pless– I note the points that Harrison and Pless apparently believe this section will prove to readers.

“Women in the History of the Church” by William Weinrich– Weinrich attempts to show that while women were “learned and holy” in the history of the church, they were not and shouldn’t be pastors.

Why I Left the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod: By Their Fruits… (Part 1)

For several posts, I will be writing about specific things that came up while I was within the LCMS–that is, at its schools, churches, and university–that made me start to think that the LCMS way of things didn’t align with some aspect of reality, what I learned in the Bible, or something else. Here, I’m starting a miniseries within that about the fruits of our actions and how they tell about who we really are.

Points of Fracture: By Their Fruits… (Part 1)

“Thus, by their fruit you will recognize them.” – Matthew 7:20 (NIV)

Earlier in this series, I wrote about my time in the LCMS. I recalled: “What I thought when I decided to become a pastor is that I’d find a group of like-minded men… I did find several like-minded men, but I also found some of the most inward-looking, doctrine-obsessed, orthodox-rabid, self-righteous, and, unfortunately, misogynistic people I’d ever run into. I was one of them for a while.” Here, I begin a series in which I share my firsthand experience within the LCMS of people–pastors, those studying to go to seminary, and seminarians, primarily–showing the fruits of the LCMS. I have to share insights into my own background, too, because I was, as I said, unfortunately “one of them” in many ways for a while.

Due to the nature of this series, in that it is about why I left the LCMS, most of these posts are negative. I do here want to start with a positive, though. I want to make it very clear that in college I encountered a number of professional LCMS theologians and scholars, including pastors (many of whom were professors) who were and are great examples of humility, pastoral concern, and even equity. Some of these stories intersect with them. My experience with the LCMS is not universally negative, of course. I received quite a bit of real pastoral care from LCMS pastors and other professionals. That said, the experiences I had interacting with fellow seminarians and other pastors led me to believe that there was, at the core, something within the LCMS producing bad fruit. ‘By their fruits you will know them,’ spoke our Lord. The fruits of the LCMS are, at the most generous interpretation, ambiguous.

One of the things that drove me out of the LCMS was encounters with its pastors’ behavior as well as the acts of those who were studying to be its pastors. That sentence seems backwards. Thinking about the behavior of people, pastors are held to quite high standards. My time as a pre-seminary student, preparing to become a pastor, exposed me to some of the worst behavior I’d encountered from other Christians. This post has a lengthy story, but it helps draw out some of the themes I experienced time and again. It helps show how my own attitude shifted as I discovered how people who were growing to be leaders in the LCMS behaved did not align with what I’d been taught.

At the LCMS University I attended, we had Spiritual Life Representatives, (SLRs), who were essentially a kind of faith-focused RA equivalent. I was offered the position as one in my junior year, and took to it with gusto. From my own experience (part of which I wrote about in my previous post), I saw the role as almost a protective one–one in which I was to be there to help guide and shepherd my dormitory of students and help them connect with their faith lives.

Fairly early on in my time in this role, a series of pranks back and forth between cross-campus dorms started. The general consensus was it was all in good fun. We had a big water balloon fight early on in the year that involved at least a little bit of attempted sabotage. The pranks kept escalating, though. Our dorm had a large cross that members of our dorm would burn our names into. It was a kind of rite of passage, and the day we signed the cross, the members of my dorm would have a cookout. It was a hugely positive experience of belonging and bonding. Anyway, our rival dorm went to extreme efforts to steal this cross. I admit, the first time I thought it was kind of funny, but then I realized how upset some people in my dorm were getting about it.

The pranks continued. I don’t remember the exact details, but many of them centered very specifically around trying to upset one member of my dorm, likely because he was the one who got most upset by them. I think it was a kind of “poke the bear” mentality, trying to see how much of a rise they could get out of him.

It was around this time that I had taken place in my own kind of rivalry-stoking. I had a Martin Luther costume for Halloween and decided to put it on and take pictures in our rival dorm while they were all in class or elsewhere. I put it on Facebook–pictures of me preaching to the heathens or whatever in the other dorm. I thought it was a pretty good joke at the time. One or two students from the other dorm were incensed though, especially given my general attitude that we needed to cut out the pranks because of how much they were upsetting some people. They commented basically calling me a hypocrite, saying if I wanted to end the pranking I needed to lead by example, etc. It was very clear from their comments that much of this was sarcasm. I went back and forth a couple times. Then I found myself typing up a long response about how I was kind of justified in my own mind and the like. Then, just as I was about to send it, I felt that it was wrong. I felt I was in the wrong. Even though they were just trying to throw things in my face and I doubted whether they were actually upset–that didn’t matter. Maybe they were truly upset, and they certainly weren’t wrong–even if they were being sarcastic–that I needed to lead by example. So I deleted the comment and took down the pictures. I realized that I did need to lead by example, and thought that if I didn’t start now, why would anyone else try?

I finally went to speak to student leadership of the other dorm, explained the situation from my view–that the way they were behaving was causing real annoyance and anger in my dorm–and asking them to stop. I appreciated the willingness to meet and talk about it, but was basically told that people in my dorm needed to cool it and not take things so seriously. When I tried to point out that those of us involved in this were largely all people studying to be pastors or LCMS teachers, and that we should live lives worthy of that calling, I was literally laughed off.

One person in my dorm who was leaning towards agnosticism from being in the LCMS, as he was witnessing these events, came to me and said that it was things like this that led him to think Christianity wasn’t for him. If Christians treated each other this way and laughed off real concerns others raised, why bother with Christianity at all? I don’t remember what I said; I think it was something like Christianity could still be true even if Christians behaved badly, and I think I also apologized for the acts. But what was there, really, to say? I knew this young man had a point, and it was one I’d contemplated myself. If we, LCMS Lutherans, many of whom were studying to be pastors or teachers to train the next generation(s) of believers, couldn’t even lay off pranks that were causing real emotional trauma to others, what did that say about us? Another student who was struggling with his faith came to me and said similar things, essentially that he didn’t want to be considered a Christian any more given the way Christians–especially those who were studying to be pastors and religious teachers–treated each other here. The situation had evolved past silly attempts to sabotage another dorm’s balloon stockpile before a water balloon fight and had turned into something that was actually impacting people’s faith lives in real, measurable ways. They were coming to me and telling me that in almost those exact words.

I finally decided to go to a grown up about the situation. Yes, we were all adults, but this seemed to need intervention or at least advice on a level higher than myself. I asked one of my professors to speak with me about the issue. I sat wtih him for a while describing the situation, not mentioning names, but talking about the details of the pranking incidents, such as who they were against, the targeted antagonism, the fact that at least two different students had approached me about how it was impacting their faith and beliefs, and more. I ended up weeping in front of this professor because I was so intensely upset by the situation. It genuinely did not make sense to me that other Christians would not listen to me about this real impact their actions were having on others.

The professor was very concerned. He said he was especially upset that I was suggesting people who were pre-seminary were involved in this situation. I don’t remember the exact details, but I do remember it becoming clear that he wanted names so he could follow up, and he wanted to take serious action to sort things out. It was what I thought I wanted going in, but I was scared, and probably a bit cowardly. I feared this would lead to people getting taken out of pre-seminary programs or LCMS teaching programs. I didn’t want to name names, in part because I didn’t want to deal with the potential fall out. I ultimately said I’d try to figure it out myself.

The pranking did fall off the wayside fairly quickly after that. I had another conversation with a few people who had friends in the rival dorm and also took the roundabout way of talking with the instigators’ girlfriends to see if they could quell tensions. To this day, I suspect that the professor may have done some digging and helped behind the scenes too. That professor is an example of one of those LCMS leaders who genuinely cares and remains a positive impact on my life.

One of the students on the ‘other side’ of the controversy was especially angry with me, personally, though I’m not sure why. Years later, at which point I’d basically forgotten who he was, he attacked me on a friend’s Facebook post, firing vitriol and curses at me that went far beyond the brief disagreement we had. It was a reminder of just how amateur and juvenile we all were in college. But it was also a stark reminder that that kind of attitude is frequently tolerated and even cultivated within the LCMS. Disagreement there is often not able to end on amiable terms. Because of the doctrinal stance that everything is black and white, it means even ultimately dumb things like some controversy over whether pranking is harmful yielded dramatic, ultimately divisive stances.

These weren’t just random people in the pews, potentially disengaged from the theology. All the men involved in this large pranking controversy (I don’t know what else to call it) were people studying to be church workers. But even when someone came to them, told them the genuine spiritual problems that were happening because of their actions, and asked them to stop, they wouldn’t. It was a disturbing time for me. It was one in which I had to realize professed faith and lived faith didn’t always or even often align. And, as I’d discovered, I wasn’t immune to it.

Next time: By their fruits (part 2) will highlight a number of examples of fruits-based acts that I encountered.

Links

Formerly Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod (LCMS) or Wisconsin Synod (WELS)– A Facebook group I’ve created for people who are former members of either of these church bodies to share stories, support each other, and try to bring change. Note: Anything you post on the internet has the potential to be public and shared anywhere, so if you join and post, be aware of that.

Why I left the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod Links Hub– Want to follow the whole series? Here’s a hub post with links to all the posts as well as related topics.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.