bible

The Bible as Human word and God’s word in Bonhoeffer- God’s Word as “other than” and historically bound

I have said many times that the Lutheran view of the Bible is actually antithetical to doctrines like inerrancy. I say that for a number of reasons. The first is that reading Luther commentating on things like the book of James makes it very difficult to think that he would have held to inerrancy. But more concretely, I make this claim because Lutheran theology affirms that the Bible is both human word and God’s word. And as human word, it can indeed have error, even as this doesn’t undermine our ability to use the Scripture as normative for our faith.

Such a claim seems odd to outsiders and even insiders like me who grew up believing that one had to affirm inerrancy of Scripture or just throw the whole thing out. How could one affirm both that the Bible could have error and still take it as authoritative? Analogies could be made here (such as knowing a rulebook for a game has a misprint or an error in it and still using it for the rules of a game–and one could make this even more complex, imagining a massive, rules-heavy game like a tabletop role-playing game and how often those do have some foibles with the rules, yet players manage to make entire masterpieces of storytelling and gaming despite those), but I also think it is good to look at what people write about Lutheran theology related to this issue.

Michael Mawson’s book, Standing Under the Cross: Essays on Bonhoeffer’s Theology is a thought-provoking collection of looks at Bonhoeffer’s views. In one essay, “Living in the forms of the word: Bonhoeffer and Franz Rosenzweig on the Apocalyptic Materiality of Scripture,” Mawson makes a series of points about Bonhoeffer’s view of scripture that hammers home what I was claiming above:

“…Bonhoeffer consistently understands the Bible as God’s word and witness to Christ… from our side we are to attend to these texts as the place where God claims us and directs us towards Christ.

“On the one hand, this suggests that attending to the Bible as God’s word requires affirming the alterity of the biblical texts. In these texts, God comes to us and encounters us from without… there is always a sense in which the texts themselves stand over against us. As God’s word and witness, they continually exceed and disrupt our best attempts to interpret and make sense of them…

“On the other hand, Bonhoeffer is clear that reading the Bible as God’s word and witness – in its alterity – in no way undermines its status as a set of fully human and historical texts… God’s word remains bound to human history and language. As Bonhoeffer continues, ‘the human word does not cease being temporeally bound and transient by becoming God’s word.’ The Bible, as God’s word and witness to Christ, is bound to all the ambiguities and contingencies of history. We encounter God only in the unstable and fragile histories and lanugage of the Bible’s authors, not otherwise or more directly….” (41)

Mawson here notes what Bonhoeffer holds, apparently without internal tension: that the Bible can both be seen as “other than” us, as coming to us from without, while also being bound within human history, understanding, and language. And as such, the Bible cannot be embraced as some kind of systematically affirmed inerrant text. Indeed, that would be to effectively di-divinize Scripture, making it something that could be wholly analyzed and understood by human endeavor. And this point absolutely must be emphasized, for Bonhoeffer’s–and Luther’s–theology, God is found in weakness. This is, again, the theologica crucis – the theology of the Cross. God is experienced as the God who suffers, who comes to us in weakness, not in dominance and conquest. And this is indeed reflected in God’s word being delivered to us as well, even in the form of human fragility and language.

Mawson makes this point again in a later chapter, entitled, “The Weakness of the Word and the Reality of God: Bonhoeffer’s Grammar of Worldly Living.” In this chapter, Mawson’s focus is more upon Christian discipleship, but here he again affirms Bonhoeffer’s Lutheran perspective as seeing God in weakness, specifically in the Scriptures themselves: “As [for Bonhoeffer, so] with Luther… God’s presence in revelation – in Christ and through Scripture – remains a hidden presence. In both cases, GOd’s revelation remains concealed under the form of fragility and weakness… God’s word is ineluctably tied to human suffering and weakness” (56).

Therefore, for both Bonhoeffer and Luther (certainly excellent representatives of the Lutheran perspective on Scripture), Scripture as God’s word does not and indeed cannot entail that is perfection in whatever human terms we come up with–inerrant, for example. Instead, God is found exactly in human weakness and fragility. Scripture itself, due to it being written by humans, must remain bound historically, linguistically, and otherwise to humanity, despite still being God’s word.

Again, this may seem paradoxical to people from traditions that firmly affirm inerrancy. But Luther and Bonhoeffer would, as can be seen from their writings on human weakness in Scripture, see inerrancy as a human effort to make comprehensible Scripture and therefore put God in a box, rather than to elevate Scripture. Ironically, by clinging desperately to a human-made definition of what the word of God must be in order to remain the word of God, they have put that very word under human authority.

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Inerrancy With No Autographic Text?

The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, perhaps the most well-known and oft-cited affirmation of biblical inerrancy, declares that inerrancy as a doctrine applies explicitly to the autographic text of Scripture- “Article X. WE AFFIRM that inspiration, strictly speaking, applies only to the autographic text of Scripture, which in the providence of God can be ascertained from available manuscripts with great accuracy.” The reality is that inerrancy as defined by the majority of inerrantists, including the Chicago statement, simply cannot stand up to the reality of how the Bible was formed. What makes this point most starkly, in my opinion, is that conservatives who affirm inerrancy are now finding themselves in the unenviable position of learning and having to acknowledge that for some of the Bible, the very concept of an autographic text is an impossibility.

One example of this is Benjamin P. Laird. Laird is associate professor of biblical studies at the John W. Rawlings School of Divinity of Liberty University. Liberty University’s statement of faith includes a clause about the Bible which states, in part, “We affirm that the Bible, both Old and New Testaments, though written by men, was supernaturally inspired by God so that all its words are the written true revelation of God; it is therefore inerrant in the originals and authoritative in all matters.” Once again, at question is the “original” text of Scripture. But what if there is no original? I want to be clear, I’m not asking the question, which is oft-discussed in inerrantist writings, of what happens if we don’t have the original. Textual preservation has made that almost impossible for any ancient text, and inerrantists have long argued that this is no problem because while inerrancy only applies to the original or autographic text, the Holy Spirit has worked to preserve the text faithfully to the extent that we can be assured that we know enough to have proper faith and practice.[1] No, the claim I’m discussing isn’t whether we have the original text, but whether we can definitively point to any (imagined) autographic text as the original or the autograph at all.

Laird’s discussion of autographs in his book, Creating the Canon, is informative. The book focuses on the formation of the canon of the New Testament. Laird notes that the longtime assumption of [some] scholars was that the original text was the inerrant one. However, he goes on to look at how letters and other works were produced in antiquity, including a number of difficult questions this raises: “When we refer to an original autograph, are we referring to the initial draft of a work, a later revision or expansion, the edition that first began to circulate, or to the state of the writing at some later stage in the compositional process?” (48). Additionally, after noting that “it would seem most appropriate to identify the original autograph of a work not as the initial draft but as the final state of the writing that the author had reviewed and approved for public circulation” (49), he notes that letter writing in the ancient world often included the writer using a scribe and having that scribe produce “one or more duplicate copies” for themselves, including copies that may have differed depending upon the audience to whom they were sent (49, 54ff).

A concrete example is the ending of Romans, which Laird notes has some problematic textual history (56-57). After noting the difficulty of determining just how long the “original” letter to the Romans was, Laird notes various scholarly responses, including the possibility that there were two different “original” editions of Romans, one with a longer doxology that would have been intended for local audiences and one which omitted it, which were eventually combined (60-61). This leads to the remarkable conclusion that “it is a strong possibility that at least three copies of the text of Romans were produced at the end of the compositional process: one for the Romans, one for those in Corinth, and one for Paul and/or his associates” (61-62). In the conclusion of this fascinating section, Laird states, “Rather than assume that the compositional process of the canonical writings culminated with the production of a single ‘original autograph,’ it is therefore best to think of something that might be described as an original edition” (64).

I admire Laird’s dedication to highlighting the problematic nature of the concept of “autograph” when it comes to the biblical text, but have to wonder what kind of cognitive dissonance that might create for someone who teaches at a place where the statement of faith explicitly refers to inerrancy in the “originals.” Sure, Laird could punt the issue to whatever he means by “original edition” as opposed to “original autograph,” but at that point, what does inerrancy even mean?

I affirmed and defended inerrancy for many years. I finally let go of it for a number of reasons which are largely beyond the scope of this post. But I understand inerrancy, and understand how to defend it. I have even done so on this very blog. What I know included things like we defended the doctrine as applying to the autographic text. But if, as Laird and many, many others are pointing out, it’s true that there is no autographic text for at least some of the Bible, how can a defense of inerrancy even make sense? It’s like a constantly retreating battle for inerrantists: declare the Bible inerrant; but which Bible?; declare it only applies to the autographs; but we don’t have the autographs; so say that the autographic text is preserved at least to the extent that it doesn’t impact essentials of the faith; but autographs don’t exist to begin with. What’s supposed to follow that? For Laird the answer seems to be “say the original edition is inerrant.” But what is an original edition? And Laird’s questions, which are quite helpful, would absolutely apply to any such discussion- is it the drafts made along the way to the “final product,” and which final product- the one(s) Paul kept for himself or the one(s) to the local church or the one(s) to the church(es) at large?

The massive import of these questions for any doctrine of inerrancy must be made explicit. The Chicago Statement makes its stand upon the autographic text. If there is no autograph to which we can point, that statement falls. Almost every definition of inerrancy in modern times does the same. They are written as if we could travel back and time and point to a text, fresh off the pen of a scribe or writer, and say “this text is inerrant.” The reality is that not only do we not have such a manuscript today, but it is becoming increasingly clear that such a scenario needs to be rewritten, with a number of different texts directed towards different audiences, with different inclusions and exclusions in the text. Would the time traveler have pointed to a text of Romans with a doxology or without it? Would they point to a work in progress or a final draft? Would certain stories that seem to have been edited into the text be part of the inerrant text or not? The time traveler scenario is now complicated beyond imagining. We don’t have a single text of Romans we could point to definitively and say “there it is.” This is admitted even by those who wish to affirm inerrancy. And so again, what does it even mean to affirm that doctrine?

It’s worth at this point stopping the discussion to ask a simple question: is inerrancy worth it? Is there something about inerrancy that makes it an unassailable doctrine that all Christians must affirm such that we must continue to circle the wagons in ever smaller circles in order to try to be able to point at something that is inerrant in Scripture? Or–hear me out–or is it possible that evangelicals have made the wrong thing inerrant? Instead of making a text inerrant and essentially equivalent to God, what if we allowed that place to stay with Christ, the God-Man Himself, and the person whom the Bible attests as the divine Word of God? This has been, historically, the position of the church[2], and is a position which requires far less retreating whenever a new discovery is made that seems to call into question some potential error in the Bible or some problem with how modern statements on how the Bible must work are read. Rather than trying to constantly revise and salvage a doctrine that appears to need a revisiting every few years, Christians should focus instead upon God, whose steadfast love never changes.

Notes

[1] See, for example, the Chicago Statement, again Article X- “WE DENY that any essential element of the Christian faith is affected by the absence of the autographs. We further deny that this absence renders the assertion of Biblical inerrancy invalid or irrelevant.”

[2] A history of the doctrine of inerrancy is very revealing and shows it to be a largely American invention in the late 19th to early 20th centuries. The statements on this doctrine were not found in ecumenical councils, nor creeds, nor really anywhere until the 20th century. Efforts to read the doctrine back onto history are just that- reading into history rather than reading history. For example, there is not discussion of the “autographic text” in early Christian writings on the canon. They didn’t even have a concept of why that would be important. The doctrine is totally dependent upon post-Enlightenment and modernist categories. Ironically, it is parasitic upon textual criticism, developing essentially in opposition to that which those who affirm the doctrine wished to deny. When textual criticism pointed out difficulties in the text as it stood, inerrantists punted the doctrine to the autographs. This is just one example of how inerrancy is entirely dependent on categories foreign to historical Christian doctrine or to the Bible itself.

As a Lutheran, an additional note- I mention here the Lutheran church explicitly because even in the earliest times for Lutherans, some Lutherans–including Luther–had questions about the canonicity of some accepted books of the Bible, along with some other issues that were raised. Lutherans have held almost from the beginning that, as Luther said, the Bible is the cradle of Christ; the Bible is not God. Some Lutheran denominations today hold explicitly to inerrancy (eg the LCMS and WELS), but this does not seem continuous with global Lutheranism or Lutheran doctrine specifically.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the New Testament”

When I saw the First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the New Testament was coming out, I was intrigued. What kind of new things might it bring to the table? The editors of this version provide some explanation of choices made in the brief introduction. For example, they translated names while leaving the Anglicized version of the name in parentheticals in smaller font. Thus, Jesus is “Creator Sets Free (Jesus)” whenever the name appears. The editors tried to bring as many First Nations peoples into the process as possible, but of course there are so many that it wasn’t possible.

Even small things like the decision made about names made for some fascinating reading as I saw so many names with meanings I would have known if I’d sat and thought about them (or consulted my Hebrew or Greek Lexicons if I couldn’t remember the roots), but that I never had done the work for. It was amazing time and again to see these names with their meanings right in front of the reader.

The editors also added occasional italicized texts to help the story get told in a more oral fashion. Thus, there are occasional places in the text where an italicized portion (which the editors make very clear are not part of the original text, but there to help emphasize the oral recitation/hearing aspect of the text) adds some flare, such as Jesus “turning powerfully” to do something or confront someone. There are also some explanatory notes, italicized and set apart from the text that offer either context for passages or additional insight into reasoning behind some of the passages. For example, 1 Peter 3, with its discussion of the Flood and Baptism (translated as “purification ceremony”), has a brief explanatory note about the Flood so hearers unfamiliar with it may know what’s happening. These italicized portions are a remarkable addition that makes the text more readable and which give key insights into some passages.

I was driven near to tears time and again by the beauty of the text. I knew that “Jesus” meant “He Saves,” but to see Jesus’s name time and again translated as “Creator Sets Free” really drove the point home in a way that knowing it abstractly didn’t do. Headings occasionally made me sit back and think, such as the Transfiguration (Matthew 17:1-13) having the heading “He Talks to the Ancestors.” Growing up and hearing how “ancestor worship/veneration” would be seen as syncretism and bad, I had never thought of this particular passage as a species of the same. It’s just a fascinating and challenging way to put the passage, an this happens many times throughout the NT (another example is the Temptation of Christ being called in Mark, “His Vision Quest”). Parables are sometimes reworded entirely, such as substituting horses for talents (the coins) in some parables. These are examples of contextualizing the NT and I found them to be quite beautiful.

One way I analyze a translation of the Bible is by looking up some specific passages and seeing how they are translated. One I look at is Romans 16:7. This passage has a history of obstruction, as some biblical scholars have attempted to turn Junia into a man due to her being listed as an apostle. I was gratified to see the FNV translation: “I send greetings also to Victory Man (Andronicus) and Younger One (Junia), my fellow Tribal Members and fellow prisoners, who have a good reputation as message bearers. They walked with the Chosen One before I did.” The translation as “message bearers” is interesting, as the same term is used occasionally for the disciples (eg. Matthew 10:1). Thus, the FNV does a good job noting that Junia was both a woman and among the apostles/disciples/etc. Of course, this study shows that some of our theological interests aren’t necessarily shared by the translators of the FNV, as they are more free with using varied terms for offices than some other translators are. Again, the equivalence between “disciples” (translated in various way) as “message bearers” and “apostles” as the same suggests this.

Other passages are 1 Timothy 3, in which many translations add masculine pronouns where the are none. The FNV reads naturally on this section, speaking of spiritual leaders. Problematic passages like 1 Corinthians 11:5-6 have explanatory notes (see above) that show how the cultural expectations may be applied here, and contextualizing it for First Nations believers (in this specific passage, with a reference to women not sitting around the drum).

Overall, time and again I found some of the more difficult passages translated in ways I thought caught the meaning of the text. Some were given explanatory notes, while others were not. It’s clear the text provides one of the more egalitarian readings of the New Testament in any translation. Additionally, discussions of Baptism (called the “Purification Ceremony”) and the Lord’s Supper are well done.

The First Nations Version is a phenomenal work. It is poetic, beautiful, and striking time and again. It captures the feel of hearing God’s word spoken, and it corrects some mistakes other translations make. I cannot recommend it highly enough. I honestly might start using it as my preferred version for personal reading. It’s that wonderful.

Disclaimer: I was provided with a copy of the book for review by the publisher. I was not required to give any specific kind of feedback whatsoever.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: ” Letters for the Church: Reading James, 1-2 Peter, 1-3 John, and Jude as Canon” by Darian R. Lockett

Darian R. Lockett provides an introduction to numerous books of the Bible in Letters for the Church: Reading James, 1-2 Peter, 1-3 John, and Jude as Canon. These books of the Bible are often entirely overlooked or skimmed through simply for the sake of proof texts or quotes, but Lockett makes a case for reading them canonically–that is, set within the whole of Scriptures. To that end, he provides summaries of each book along with discussion of major themes, specific points of instruction and other interest, and more.

Lockett tackles several of the more difficult issues related to these books of the Bible throughout. Authorship is a major question, and he largely presents the evidence for who is thought to have authored the book, what evidence we may have for that, and his own conclusions. Another example of Lockett dealing with a more difficult issue is with Jude’s use of non-canonical works to make points in its own text. Jude clearly uses 1 Enoch in Jude 9, and this raises the question of whether Jude saw 1 Enoch as an authoritative or inspired work. Lockett notes that it has been a thorny issue through much of church history before outlining a few major points. Ultimately, this reader wonders whether the specific interest in whether Jude lends to making 1 Enoch inspired or canonical is a kind of anachronistic concern with reading over our ideas onto the text. Lockett’s own analysis could yield that, as he notes that what we can ultimately say is that 1 Enoch was “an important part of [the author of Jude’s] argument and [that author] does not distinguish it from other prophetic texts from the Old Testament–beyond this we can only speculate” (205).

Lockett also doesn’t shy from some of the more hotly debated texts within the books he’s writing about. For example, the question of wives submitting to husbands in 1 Peter 3 is discussed at some length (77-80). Lockett notes the context regarding doing so for the sake of Christ, and ultimately aims at the notion that such submission could potentially win non-Christian spouses over, which makes more sense of other parts of the book as well. Reading 1 Peter 3 as an intentional way to tell all wives to submit to all husbands in all circumstances, as is often done, is therefore a mistaken reading of the text.

Letters for the Church is a strong introduction to numerous books of the Bible that are often skimmed over. No matter where readers come from theologically, it is an enlightening, challenging read. Recommended.

Disclaimer: I was provided with a copy of the book for review by the publisher. I was not required to give any specific kind of feedback whatsoever.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Every Leaf, Line, and Letter: Evangelicals and the Bible from the 1730s to the Present” edited by Timothy Larsen

Timothy Larsen is an author whose works have fascinated me time and again, so when I saw his edited volume on evangelicals’ reading of the Bible, I knew I had to hop in. Every Leaf, Line, and Letter: Evangelicals and the Bible from the 1730s to the Present is a superb look at some specific ways evangelicals have engaged with the Bible throughout the last several centuries.

Collections of essays are often hit-or-miss affairs, but Larsen has compiled a selection of essays full of excellent topics and insights. The essays are grouped by century, starting in the 18th and terminating in the 21st. They rnage fro mearly evangelical readings of the Bible to global evangelical mindset in today’s contexts. Instead of providing an overview of every one of these great works, I’ll highlight a few I found especially insightful.

With “British Exodus, American Empire: Evangelical Preachers and the Biblicisms of Revolution,” Kristina Benham introduces readers into the ways in which American evangelicals and their British forebears used the biblical narrative–particularly those of the Exodus–to draw parallels to their own situations in colonial and Revolutionary America. It’s a fascinating look at how one’s own context can shape how one reads Scripture. Mark A. Noll’s “Missouri, Denmark Vesey, Biblical Proslavery, and a Crisis for Sola Scriptura” engages with readings of the Bible and advocates of slavery. Indeed, at times the proslavery position claimed the high ground of reading the Bible more literally or even accurately than did those who opposed slavery. Such readings of the Bible in evangelicalism are too often ignored or skirted around.

Malcom Foley’s essay about resisting lynching, “‘The Only Way to Stop a Mob’: Francis Grimke’s Biblical Case for Lynching Resistance” seems poignant to this day, despite being part of twentieth century readings of Scripture. Catherine A. Brekus’s examination, “The American Patriot’s Bible: Evangelicals, the Bible, and American Nationalism,” shows how evangelicalism in the 21st century has so often conflated nationalism, patriotism, and theology. Her detailed analysis of what may seem an aberration also highlights how emblematic of American Evangelicalism the American Patriot’s Bible actually is.

This short sampling of just a few topics out of the 12 essays offered shows the broad array of topics available to the reader. I can’t emphasize just how refreshing this collection was. Yes, the topics are focused around a single subject: evangelical readings of the Bible; but they did so from such broad categories that each essay felt it broached new and intriguing avenues of exploration for the reader.

One drawback of collections of essays does loom here, though: there is, again, an unbalance in authors selected. I’m unsure of the racial breakdown in authorship, but the contributors are heavily weighted towards males, with at least 2/3 being men. Though each essay is excellent on its own merits, one wonders whether there couldn’t have been more attention paid to a diversity of voices.

Every Leaf, Line, and Letter gives readers a broad swathe of topics related to evangelicals’ reading of the Bible both past and present. Each essay brings a unique perspective and whole avenues of new reading and insight along with it. This volume is highly recommended.

Disclaimer: I was provided with a copy of the book for review by the publisher. I was not required to give any specific kind of feedback whatsoever.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Yes, Christians (and I’m looking at you, apologists) should affirm that Black Lives Matter, and here’s why

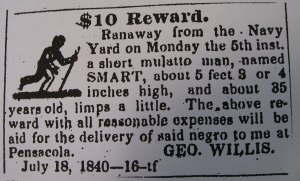

Image Credit: By George Willis, Navy Agent Pensacola Navy Yard placed July 18 1840. – Pensacola Gazette, runaway slave reward for “SMART” dated July 22 1840,p.3 National Archives and Records Administration Washington DC, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68445221

When justice is done, it is a joy to the righteous,

but dismay to evildoers.

I have an MA in Christian Apologetics. Because of the circles I run in due to my interest in apologetics, I’ve seen dozens, if not hundreds of posts bemoaning Christians supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. These posts often center around the notion that the organization Black Lives Matter is inextricably tied to critical race theory, which itself is alleged to be completely anathema to Christianity.

I’m going to suggest the opposite. I’m going to say Christians absolutely must support Black Lives Matter as a movement because black lives do matter. Full stop. And this argument doesn’t need to be over whether critical race theory may be used by Christians or not. I don’t need to wade into those waters for my point.

If you’re asking the question “Should Christians support ‘Black Lives Matter’?” the first thing you should ask immediately following that question is a simple one. Do black lives matter? If they do, then you’ve answered the question. And the reason I’m saying this is because the answer needs to be simplified. People have been, intentionally or not, conflating the entire movement with one organization with which they disagree. I’ve directed this post somewhat at apologists because I’m an insider there, and I’m quite frustrated. We need to do better, fellow apologists, at leading the way as people who want to be thought leaders in Christianity. We need to do better. We need to express more care with our thinking, while also expressing more care for following what the Bible actually tells us to do.

You see, no Christian apologist worthy of the name would agree that if an organization arose that went around saying #JesusisLord, every Christian ever has to agree with everything that person or organization says or does. yet it is a fact that Jesus is Lord. Right? Right? But it would be absolutely absurd to insist that every single person who ever has said anything like “Jesus is Lord” or #JesusisLord must therefore be intrinsically tied up in whatever the organization or person who made the phrase popular said or did. Indeed, looking at the history of Christianity, we better be very, very careful to make the point that support of a statement–even one made by members of an organization with the same name as a movement–does not entail support of everything in that movement or organization. If that were true, then all Lutherans must agree with Luther’s antisemitic statements; all Southern Baptists need to agree with the many, many antebellum Baptists who preached pro-slavery sermons; all Christians have to be indicted by the raping that occurred during the Crusades; and the sad, awful, and sordid history of every aspect of Christianity anywhere done by anyone who has ever said “Jesus is Lord” would be applied to every single one of us.

But that’s wrong, because that’s not how reality works. I can affirm Jesus is Lord without also affirming everything even every other modern Christian says. In fact, I’m sure you do the same thing. That’s because we realize that Jesus is Lord is true, but not everything said or done by Christians is true or good. Guess what: the statement “black lives matter” is true. It is.

None of this is to say that the specific Black Lives Matter organization is right or wrong about any- or everything. But I’ll tell you one thing: they are 100% totally correct in saying that black lives matter. And if you disagree with that, the problem is with you, not with the organization, not with people who you see as rioting, and not with anything else. It’s with you.

If we’re Christians, we believe the Bible speaks to us today. It teaches us to this day. The quote with which I started this post was from Proverbs 21:15. It is just one of a great many Bible passages that urge us to seek justice. And believe it or not, the way God’s justice comes is sometimes surprising. Sometimes, even the chosen people of God get things wrong. That’s why, for example, Jonah’s anger over God’s justice speaks so clearly to some of us today. We are too often like Jonah, fleeing rather than trying to bring God’s loving forgiveness to people with whom we disagree. But God is a God who works in ways we don’t always understand. God used even the ungodly to bring justice. Be careful, lest we stand in the way of God’s justice in a moment in which we as Christians should be standing up and also declaring that yes, black lives matter and yes, we should seek justice for them.

Learn to do good; seek justice, correct oppression; bring justice to the fatherless, plead the widow’s cause. – Isaiah 1:17

It’s a powerful thing when we can sit and listen to our neighbors who say they are oppressed without rushing to explain it away as an aspect of critical race theory or some other straw man we’ve set up so that we don’t have to do what the Bible tells us to do. Yes, those are strong words, and they are so needed right now, however unfortunate that is. Think about it. If you’re a Christian apologist- which have you spent more time doing of late: critiquing critical race theory and trying to correct people about the Black Lives Matter movement or actually seeking to learn from those who are crying out for help? Which do you think is more valuable for the building of God’s Kingdom?

What about lawbreakers? I chose the picture for this post for a reason. It’s from an 1840 advertisement for capturing a fugitive slave. This ad was before the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, but it is still a fact that trying to escape from slavery was unlawful. These fugitive slaves were lawbreakers. But who was in the right–the “fugitive” or the enslaver? Let’s practice some extreme, tremendous care that we do not align our Christian morality to that of the law of the state. Laws change, but God’s will and justice never change. Justice came for those evildoers who enslaved others in the United States. We should pray that justice continues to roll from God to our nation to this day.

Finally, we as apologists need to practice better care for our thoughts. When confronted by a new idea, our tendency is to analyze it, break it apart, and see how it fits together. Too often, this also becomes a practice in self-affirmation. Is it any wonder that so many apologists who were unconcerned about racism in the United States before the recent protests are suddenly up in arms about Critical Race Theory and calling on other Christians to disavow any kind of “social justice movement.” We need to think long and hard about that. Why was that our instinct–including my own? How do we break out of it? For me, it was going and actually reading books about racial injustice and disparities in the United States. Yep, we have to do that thing that apologists love doing: read books. But there’s a big caveat here: not just books that support our own views. We need to humble ourselves and acknowledge we might just be wrong on this topic, and do the work to learn about it. Because we absolutely cannot and must not make new stumbling blocks for Christianity. In my apologetics classes, I remember hearing time and again how “Christianity is offensive enough.” How do you think people feel when they see people like us–trained apologists–lining up to explain how Christians cannot support the Black Lives Matter movement, conflating it entirely with the organization? Is that actually a good witness? Is it even a good use of our time? No. It’s not. Why not? I’ll tell you:

Black. Lives. Matter.

It’s time to be humble; to act justly; and to love mercy. It’s time for apologists to do what the Bible says.

He has shown you, O mortal, what is good. And what does the LORD require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God. – Micah 6:8

Links

Book Review: “Rethinking Incarceration: Advocating for Justice that Restores” by Dominique DuBois Gilliard– Learn about our criminal justice system and how it needs to be reformed.

“Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom” by David W. Blight– A prophet for then and now- Learn about Frederick Douglass, a powerful Christian voice who helped speak for justice in ways that continue to resonate into our own time.

“How to be an Antiracist” by Ibram X. Kendi– I review and summarize major aspects of this book on antiracism on my other site.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“The Once and Future King” by T.H. White – Honor, King David, and Justice

T.H White’s classic Arthurian tale, The Once and Future King is an absolute delight to read. I had never read it before, and I was surprised to see the sheer amount of humor found therein. The depth of the work’s story is immense. Here, I will look at some of the worldview level themes found in the book. There will be SPOILERS in this post.

T.H White’s classic Arthurian tale, The Once and Future King is an absolute delight to read. I had never read it before, and I was surprised to see the sheer amount of humor found therein. The depth of the work’s story is immense. Here, I will look at some of the worldview level themes found in the book. There will be SPOILERS in this post.

Honor

Young Arthur, known as “The Wart,” shows his character in one discussion with Merlyn-

If I were to be a Knight… I should pray to God to let me encounter all the evil in the world in my own person, so that if I conquered there would be none left, and, if I were defeated, I would be the one to suffer for it. (174)

Arthur is an honorable man–and was even an honorable boy. That doesn’t mean he never makes poor choices, but he is ultimately motivated by faith and a desire to take on evil directly.

King David… Arthur

In many ways, the story of Arthur parallels the biblical story of David. Like David, Arthur desires to follow justice and walk in the way of God. Like David, it is illicit affairs which lead to his undoing. Like David, Arthur’s downfall ultimately comes from within his own family. Each has a kind of guide in the early stages of their rule (Merlyn or Samuel), but neither takes on such guidance later in life. Each is guided by faith, and it each attempts to capture a kind of ideal in their monarchy. Their ideals are never quite reached, and it is evident in the story of each that their own choices limit their capacity to reach that ideal. In the end, each turns to God for the final answers.

Justice

One of the best portrayals of justice in the book can be found in the way White portrayed injustice. The knights are operating under a principle of “Might makes Right.” They expect the lower class soldiers to be slaughtered, while they themselves are so heavily armored they can barely be harmed (as hilariously depicted in an early scene that young Arthur gets to witness). Arthur seeks to go against this principle–to wage war on Might. Yet, even that battle ends in failure as it becomes corrupted. A question the book seems to point us towards is whether violence to overcome violence is a realistic means.

The conclusion to the book catches Arthur at his most reflective. White’s own view begins to peek through the words of Arthur’s thoughts. What is it that failed Arthur? How did his quest for good become so embroiled in deceit and betrayal? Yet Arthur finds that there was a crucial flaw in his plan: “[T]he whole structure depended on the first premise: that man was decent” (637). He had forgotten about the sinfulness of humanity:

For if there was such a thing as original sin, if man was on the whole a villain, if the Bible was right in saying that the heart of men was deceitful above all things and desperately wicked, then the purpose of his life had been a vain one. (638)

The purpose was vain, because it was not pursued alongside God’s will but rather as Arthur’s will imposed upon humanity–the very thing that Merlyn had come back through time (or was it forward?) to discover. Yet that which Arthur wished to bring about–the defeat of Might–was not itself an evil end. Indeed, it is the King’s page who reveals the ultimate judgment on Arthur’s plan: “I think it was a good idea, my lord”–thus said the page; and Arthur’s response: “It was, and it was not. God knows” (644).

Ultimately, it seems, justice is defined on God’s terms and humans are incapable of seeing the whole picture. White was an agnostic, but was apparently scornful of the evil he saw in the world. A kind of pessimism about human capacities is found throughout the book. The fact that, in the end, “God knows” is the answer that can be given towards whether humans can accomplish an ideal is telling. Without God, endeavors of that sort are impossible.

Other Topics

There are some pretty interesting parables included within the text, particularly in the “Sword in the Stone” section. One of them is from the Talmud–a story in which Elijah travels with a Rabbi and perplexes the Rabbi with his apparent lack of concern for the poor while he aids the rich. Yet this parable shows that God is indeed working towards justice, and a God’s-eye perspective of justice is impossible. Another parable tells a story about humanity as a kind of capstone of creation, while limiting humanity to being an “embryo” for all time- a creature in development. This capacity-laden view of humanity points to White’s worldview once more. Human choices matter, but we so often choose poorly.

The Dark Ages, White notes, may have been a bit of a misnomer:

Do you think that they [those times sometimes called “The Dark Ages”], with their Battles, Famine, Black Death and Serfdom, were less enlightened than we are, with our Wars, Blockade, Influenza and Conscription? (544)

Here again we see White’s own world creeping back into the novel. The novel was published in 1939, the year World War II officially began, though there was plenty going on before that. It was difficult to see the War coming and think that another age was to be singled out as the “Dark” age. There is a kind of intellectual hubris in dismissing the ideas of the past and seeing one’s own time as somehow enlightened. White did not think that was a route to take.

Merlyn (yes, Merlyn, not Merlin) is a character whose interactions with Arthur bring up all kinds of questions. He seems to be guiding a young Arthur towards the attempt to bring about justice in the world, but he also allows himself–seemingly willingly–to be cast aside when Arthur is at his most vulnerable. He only reappears at the very end of the book as a kind of wind. I am left feeling rather ambivalent about Merlyn, who had so much power but who did not ultimately use it very effectively.

Conclusion

The Once and Future King is a simply phenomenal book layered with many levels of meaning. There are so many avenues to explore from a worldview level that I’m sure repeated readings will be rewarding. The central theme, however, is incredibly powerful: humans cannot complete their own ideals. We are imperfect. God knows.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Popular Books– Read through my other posts on popular books–science fiction, fantasy, and more! (Scroll down for more.)

Source

T.H. White The Once and Future King (New York: Ace, 2004 edition).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“Jesus was a Young Earth Creationist” – A Problem

“Haven’t you read,” he replied, “that at the beginning the Creator ‘made them male and female…'” – Matthew 19:4 (NIV)

“But from the beginning of creation, ‘God made them male and female.’”- Mark 10:6 (ESV)

Jesus states here that God made human beings. These passages have been used for any number of exegetical points, but the one I want to focus on now is that of certain Young Earth Creationists. Almost without fail, when I have a discussion about creationism and what the Bible says about creation, it is asserted that “Jesus was a young earth creationist.” When I ask for evidence of this claim, one (or both) of these verses inevitably are raised. But the question is: do these verses actually say what Young Earth Creationists (YECs) want them to say?

The implication the YEC wants to take from these verses is that humans were on the stage at creation, so there could not have been any millions or billions of years of time from the start of creation until humans arrived on the scene. Thus, by saying that “at the beginning” or “from the beginning of creation” humans were created and on the Earth, the YEC argues that Jesus was endorsing and giving evidence to their position.

It ought to be clear from this that the YEC must read these verses quite literally for this implication to follow. After all, the point of this passage is definitely not to speak to the age of creation–Jesus is making a point about divorce in context. Thus, to draw from these passages a young earth, the YEC must insist on a strictly literal reading of the passage and then draw out the implications from that literal reading. The problem for the YEC, then, is that on a strictly literal reading of this passage, the implication becomes that Jesus was mistaken; or at the least, that the YEC position is mistaken on the order of creation.

Read the passages again. They don’t merely say that humans were created in the beginning. Rather, they clearly state that God created them male and female “at the beginning” or “from the beginning of creation.” This must not be missed. A strict literal reading like the one required for the YEC to make their point from these passages must also take literally the word beginning. But if that’s the case, then it becomes clear the YEC reading of this passage breaks down. After all, humans in the Genesis account were the last of creation. They were the final part of creation. But these passages say at the “beginning” not at the “end” of creation. So if the YEC insists that we must take these words as literally as they want us to in order to make their point that Jesus is a young earth creationist, they actually make either Jesus, Genesis, or their own reading of the creation account wrong. Again, this flows simply from the way the YEC insists upon reading these texts. If Jesus says that humans were made at the “beginning” of creation and Genesis literally teaches that humans were the end of creation, then something has to give.

Counter-Argument

The most common objection I’ve gotten from YECs as I make this point is that my own position still would not be justified in the text. After all, if the Earth is really billions of years old, and most of that time lapsed without any humans being around, why would Jesus then say that “at the beginning” or “from the beginning of creation” humans were around? A fuller answer to what Jesus is saying in these passages is found in the next section, but for now I’d just say it is pretty clear that Jesus is making a point unrelated to the time of creation and simply using language anyone would understand. “Back in the day”; “ever since humans have been around”; “for as long as anyone knows about”; these are ways that we can make similar ideas shine through. Moreover, because a strictly literal reading of this passage to try to rule out any time between creation and humans implies the difficulties noted above, it is clear that such a reading is untenable.

A Proper Interpretation?

The final point a YEC might try to counter here would be to demand my own exegesis of this text. After all, if they’re wrong about how to read the text, how do I read it such that it doesn’t make the same implications? That’s a fair point, and I’ve already hinted at my answer above. It is clear these texts are about divorce, as that is the question that Jesus was addressing. Thus, he’s not intending to make a statement about the age of creation or really its temporal order at all. He simply says “from the beginning” as a kind of shorthand for going back to the first humans. Humans, Jesus is saying, have been created like this ever since God made them. Period. The problem the YEC reading brings to this text is nonexistent, but only when one does not try to force it to answer questions it wasn’t addressing.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

What options are there in the origins debate? – A Taxonomy of Christian Origins Positions– I clarify the breadth of options available for Christians who want to interact on various levels with models of origins. I think this post is extremely important because it gives readers a chance to see the various positions explained briefly.

Origins Debate– Here is a collection of many of my posts on Christianity and science.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “The Book of Isaiah and God’s Kingdom” by Andrew Abernethy

Andrew Abernethy’s The Book of Isaiah and God’s Kingdom has a kind of dual purpose: introducing readers to the overarching themes of the Book of Isaiah and to show that Kingdom in particular is central to understanding the Book of Isaiah.

Andrew Abernethy’s The Book of Isaiah and God’s Kingdom has a kind of dual purpose: introducing readers to the overarching themes of the Book of Isaiah and to show that Kingdom in particular is central to understanding the Book of Isaiah.

Abernethy acknowledges a number of difficulties with Isaiah, including the difficulty of tying down its historical context, the problem of a “meta-history” of the book and its composition and getting to its final form, and the sheer size of it going against several attempts at a unified meaning. Nevertheless, he takes on that latter task, and on the way manages to deal with the other difficulties, at least in passing.

Abernethy traces the concept of “Kingdom” in Isaiah through five chapters that each focus on one aspect of the Kingdom: God as King now and to come; God as saving King, God as warrior/compassionate king; lead agents of the king; and the people of God’s kingdom. The first three of these provide a broad thematic overview of Isaiah, splitting it into three parts, and the latter two cover each of the three parts related to the thesis.

The book is quite dense despite having a somewhat introductory idea. That is almost certainly because Isaiah itself is so dense that in order to do it justice, Abernethy was forced to introduce a vast amount of information. What makes the book particularly useful is that Abernethy ties Isaiah not just together, but also into the canonical narrative, and this is perhaps most prominent in the God as saving King and people of God’s kingdom sections. As an example, in the section on God as saving king, there is a small (two-page) section on Isaiah 40:1-11 and 52:7-10 in canonical context which contains over a dozen references to other canonical references (this at a glance). Abernethy thus deftly balances reading Isaiah on its own terms with understanding it both in its historical and canonical context. The fact that such a sentence can be written itself speaks highly of the work.

Perhaps the biggest strike against the book is that because it does have a rather basic feeling to it, and because Isaiah is itself so dense, the work feels much longer than it actually is. It stands at 200 pages sans the appendix, but feels much longer simply because so much space is covered, with multitudes of Scriptural references on each page. This makes me question what audience the book was written towards, as beginners will likely feel it is a daunting read, while those who’ve done a good amount of reading on Isaiah already will have picked up on most of the themes contained here. That said, the book can easily serve as a great reference and tool to glance over when one wants to explore the book of Isaiah in more depth. It is about as compact an introduction–while still being useful–as one could expect.

The Book of Isaiah and God’s Kingdom isn’t trying to forge much new ground. Rather, it is a dense survey of a book of the Bible that is packed full of information. Abernethy does readers a service by helping to unpack Isaiah while sticking to broad themes rather than individual debates.

The Good

+Focus on broad themes makes it more readable

+Good reference work for themes in Isaiah

+Highlights many of the more interesting questions about the book of Isaiah

The Bad

-Incredibly dense for such a short read

-May be off-putting to some of the target audience

Really Recommended Posts 10/21/16- Reading the Bible, a pro-life argument, and more!

The What-He-Did: The Poetic Science Fiction of Cordwainer Smith– Cordwainer Smith was a Christian who also happened to be an expert in psychological warfare, among other things. He wrote science fiction that is strange and alluring and poetic all at once, and imbued with his worldview.

Spoilers– Too often, we assume that because we’ve read it before, or know the “spoilers” of the story, we know exactly what the Bible is teaching. Is that really the case?

The Most Undervalued Argument in the Pro-Life Movement– A defense of a rather simple argument for the pro-life position.

Let’s All Be Nicene– The continuing debate over eternal subordination of the Son is, frankly, disturbing to me. I think the call to be Nicene is an appropriate one. This is a post highlighting some of the issues with those who are for eternal subordination of the Son and its problems.

6 Myths About Advocating for Women in Ministry– Don’t be deceived by false arguments that advocating for women in the ministry is somehow detrimental to the church.

“Here I stand, I can do no other, so help me God. Amen.”– A brief account and reflection on Luther’s famous words.