Bonhoeffer

“Discipleship in a World Full of Nazis: Recovering the True Legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer” by Mark Thiessen Nation

Discipleship in a World Full of Nazis: Recovering the True Legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer is an alluring title that promises to push at scholarly boundaries. Any time a book seeks to “recover” a “true legacy,” there are a number of ways it could go on the subject. It could be a sensationalist look at the topic, or a more measured look at something that has, heretofore, been sensationalized. Mark Thiessen Nation seeks here to rethink Bonhoeffer’s alleged participation in the plot to kill Hitler, among other things.

Mark Thiessen Nation’s thesis is fairly straightforward: consensus scholarship regarding Bonhoeffer’s involvement in the plot to assassinate Hitler is grounded upon shaky historical ground and should be rejected in light of his apparent and actual pacifism. In order to argue for this end, he makes three early points in favor of that thesis- Eberhard Bethge leaves the impression that Bonhoeffer was involved in the plot to kill Hitler; the evidence for why Bonhoeffer was arrested point in another direction; and, finally, the starting point for evaluation of Bonhoeffer’s life, legacy, and theology ought to be located in a place other than as a resisting pastor involved in the plot to kill Hitler (3).

What is interesting is that I doubt many Bonhoeffer scholars would dispute almost any of these theses. Eberhard Bethge clearly gives the impression Bonhoeffer was involved. There’s no reasonable way to dispute that. The evidence for Bonhoeffer’s being arrested does not suggest it was due to a plot to kill Hitler. No Bonhoeffer scholar I am aware of actually suggests that Bonhoeffer’s involvement in a plot to kill Hitler is the lens through which his whole life should be read. What this means is that Mark Thiessen nation, in picking these theses early on, essentially gives himself an easy hit, teeing it up so that he can knock it out of the park. By doing so, it gives the arguments that follow a veneer of support. After all, his earliest theses were proven to be at least mostly correct! One could be forgiven for thinking the rest of the argument would flow from these points, but one would be mistaken.

An important aside about these early theses is warranted. The evidence regarding Bonhoeffer’s arrest not being related to a plot to kill Hitler does not help Thiessen Nation’s narrative, because none of those arrested around the same time as Bonhoeffer were arrested for that reason either! If Hitler had known of a plot to assassinate him, does anyone actually think he would have let those would-be assassins sit in prison rather than torturing and murdering them immediately (as he did once he discovered the plot)? The reasons for the arrests of these others is a matter of historical record, but by emphasizing that Bonhoeffer, uniquely, was not arrested due to a plot to assassinate Hitler, Thiessen Nation makes it seem as though this is some major point against historical arguments for his involvement. But that’s an unwarranted leap, again, given that the plot had not yet been discovered. No one could have been arrested for a plot that those doing the arresting didn’t know about yet! Unless Thiessen Nation is aware of some historical data that says they were aware of that plot contemporaneous with Bonhoeffer’s arrest (having read much literature on this, I don’t know of any, but I can hardly claim to have universal knowledge of the topic), this point is superfluous at best, disingenuous at worst, because it sets up readers to doubt Bonhoeffer’s involvement based on this lack of reason for the arrest.

Another salient historical point that Thiessen Nation only raises occasionally is that there is no evidence directly linking Bonhoeffer to the plot to kill Hitler. While this seems possibly correct in regards to a paper trail, it seems incorrect regarding those who knew Bonhoeffer personally. Again, this would include Eberhard Bethge. Time and again, our author here notes that there is little to no evidence for Bonhoeffer’s involvement; yet testimonial evidence is evidence, and we have that. Additionally, nothing is made of the relevant point that those involved in a plot to assassinate a brutal dictator would hardly keep everything on paper for posterity. It shouldn’t be that surprising in this case to hold to the dictum that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Still more, Thiessen Nation does not acknowledge that, after World War II in Germany, those who had worked against the Third Reich were still viewed with suspicion for many years. Bonhoeffer was not exempted from this, and it would surely be a point in favor of additional secrecy regarding those involved in any plot to kill Hitler. It’s not a particularly delightful thing to acknowledge, but all of these are facts of history that are borne out in research of the time period.

Thiessen Nation goes on to argue that various points are in favor of reading Bonhoeffer as a committed pacifist. While noting some difficulties with earlier writings, he finds great support in Discipleship and argues for this as a core point of Bonhoeffer’s ethics (see chapter 4). Then, he turns to Ethics and this is where I think the argument starts to come apart. First, he sees Bonhoeffer’s rejection of Kantian absolutism and even applauds it (125-126). This is a point often missed in examination of Bonhoeffer’s–and Lutheran–ethics generally. This ethic rejects a kind of totalitarian deontology in favor of a more situational ethic. This point would actually obviate against a reading of Bonhoeffer as purely pacifistic, as this would require a kind of Kantian commitment to pacifism, but the topic is not explored further.

Thiessen Nation next hones in on the quote from Bonhoeffer that “everyone who acts responsibly becomes guilty.” He suggests that this quote should not be read contextually related to a background of a plot to assassinate Hitler, but rather as a way of understanding the broader context of the war. This certainly resonates with me, and I think that it would make sense. Indeed, I would not personally limit that quote or the general discussion of Bonhoeffer’s thought on responsibility to his involvement (or not) in the plot to kill Hitler. If he was involved, his reasoning on responsibility certainly makes sense of how it would work within his ethical system. Taking away this involvement, Thiessen Nation casts about for another motivation for the reflection on responsibility. He lands on it coming from Bonhoeffer’s reading of letter(s) from his student(s) regarding their own involvement in the Third Reich (129-130). Such is a fascinating thesis, and allows for additional areas of research regarding Bonhoeffer’s life. However, Thiessen Nation pushes it farther, tying Bonhoeffer’s reflection on responsibility to the awful acts of his students, including “cold-blooded murder of civilians and surrendered soldiers” (129, see also 129n21). This is, in my opinion, one of the worst re-readings of Bonhoeffer I’ve read. Bonhoeffer’s entire discussion of responsibility is set against the background of becoming guilty not for oneself but for the sake of the other. To read that as a justification of “cold-blooded murder” simply because Bonhoeffer was somehow struggling to justify his students’ actions makes this a horribly motivated and specious justification for, well, cold-blooded murder! And it doesn’t make any sense of Bonhoeffer’s own words, as he wrote this all in context of taking on guilt for one’s neighbor! How could one do that if one is too busy murdering them?

I would almost second-guess my reading of Thiessen Nation here, because it seems such an off-base reading of Bonhoeffer, but he makes it quite clear that it is his intent to suggest Bonhoeffer was somehow justifying this cold-blooded murder: “Might [Bonhoeffer] have been thinking of [his students’] letters when he wrote that it worse to be evil than to do an act of evil? …in the midst of extremely difficult circumstances, Bonhoeffer is quite sensitive toward his former students who either were not convinced by his teaching on nonviolence or who couldn’t face the consequences of formally claiming to be a conscientious objector, which was a capital offense” (130). He goes on to say that “my hypothesis is more likely than any notion that he is writing reflections to justify his ‘involvement’ in any attempts on Hitler’s life” (ibid). This removes any doubt of this reading: Thiessen Nation is genuinely suggesting that Bonhoeffer wrote this section on responsibility to justify his students’ and friends’ actions of choosing to murder civilians instead of die as a conscientious objector. If he’s right in this reading, he has turned one of my favorite sections of Bonhoeffer’s work into a heinous justification of evil.

Bonhoeffer’s words themselves appear to obviate against this reading, however, because in the section on responsibility in Ethics, he explicitly states that human beings must become guilty not for the sake of themselves or their own attempts to be guiltless, but “entering into community with the guilty of other human beings for their sake. Because of Jesus Christ, the essence of responsible action intrinsically involves the sinless, those who act out of selfless love, becoming guilty” (Ethics, DBWE: 276). Where can one truly justify murder of innocent others for the sake of preserving one’s own life in this text? Where could one read it at as Thiessen Nation does? It is an utterly nonsensical reading of Bonhoeffer to read him as justifying murder to avoid capital offense.

Mark Thiessen Nation himself, according to this profile, was a conscientious objector to Vietnam. I hesitate to speculate, but is it possible that he is looking at his own situation, likely knowing others who committed awful acts in Vietnam, and trying to provide some kind of a posteriori justification for those acts, roping Bonhoeffer into such a defense?* The reading seems radically American and individualistic, putting one’s own well-being as such a high good that becoming guilty of “cold blooded murder” to avoid one’s own capital punishment is seen as good for the sake of the other. Again, none of this makes sense in light of Bonhoeffer’s own work. Thiessen Nation concludes this section acknowledging we can’t know the exact reason for Bonhoeffer’s deliberations on guilt, which would have been a better overall point (though still hotly disputed) (130). Yet this last minute broadening of scope does little to overcome the fact that he asserted earlier that his reading of Bonhoeffer justifying mass murder for the sake of one’s own life is somehow more likely than Bonhoeffer justifying tyrannicide for the sake of the other. Again, it is ludicrous to the point of the absurd to read Bonhoeffer this way in the context in which these words were set.

Belaboring the point even a little more, Chistine Schliesser, in the aptly titled Everyone Who Acts Responsibly Becomes Guilty, argues that one can see this thread of guilt for the sake of the other throughout Bonhoeffer’s entire works. It’s more complicated than that, of course, but that book offers an excellent overview of the concept of guilt in Bonhoeffer.

Another problem with Thiessen Nation’s overall theses related to Bonhoeffer’s pacifism is that he is only capable of reading Bonhoeffer as wholly pacifistic through revisionism (see the discussion above); through arguing against some early biographers and friends of Bonhoeffer (eg. Bethge- who would almost have to be accused of lying if Bonhoeffer were not involved in the plot against Hitler in any way); or through arguing that Bonhoeffer changed his mind not infrequently, only settling on pacifism after a number of other ethical stances were attempted. The former two points have been spoken for already, but I think the latter point is worth a very slight reflection. Thiessen Nation, while critiquing other authors who seek to place Bonhoeffer in his Lutheran perspective (eg. Michael DeJonge), fails to take Bonhoeffer’s Lutheranism seriously. Bonhoeffer quoted Luther more than any other theologian, and it is not difficult to trace many aspects of Bonhoeffer’s theology directly to Luther. This includes his ethics. Thiessen Nation was right earlier to note the rejection of Kantian ethics in Bonhoeffer. Bonhoeffer (and Luther) rejected deontology. This rejection allowed for a more dynamic or situational ethic that could be adjusted to current contexts rather than delivering principles that would last for eternity. It seems to me that a better reading of Bonhoeffer that doesn’t require re-interpreting or rejecting parts of his ethic would simply be to take it as a development of Lutheran ethics, in which sometimes pacifism is the right response and even perhaps a broad ideal, but at others, taking on guilt for the sake of the other is required.

Discipleship in a World Full of Nazis is a provocative look at Bonhoeffer’s alleged pacifism. I believe it largely misses the mark, and misses it badly in some cases. The author’s [with others] earlier Bonhoeffer the Assassin? (my review here) made a more limited argument. It is clear to me, having read this work, that trying to double down on reading Bonhoeffer as a pacifist will only work if one shoehorns his ethics into corners that don’t make sense contextually. Overall, I think this book does not succeed in its argument.

*Rev. Beth Wartick made this point to me in conversation.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

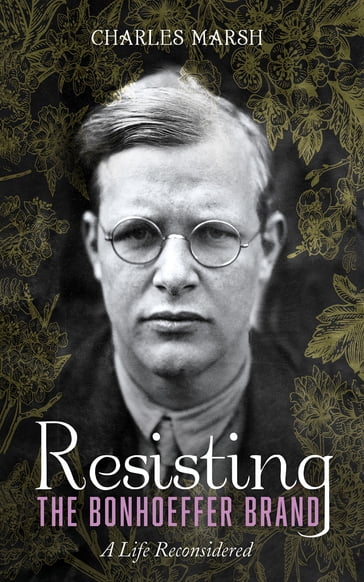

“Resisting the Bonhoeffer Brand: A Life Reconsidered” by Charles Marsh

Charles Marsh’s biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Strange Glory, sparked quite a bit of discussion when it was released. What many readers might not have realized, however, is that it also led to quite heated debate in scholarly circles related to Bonhoeffer studies. With Resisting the Bonhoeffer Brand: A Life Reconsidered, Marsh responds to scholarly critique of his biography, highlights some of the difficulties and joys of writing biographies, and calls readers to push to better understanding of the life and theology of Bonhoeffer.

The book’s short length should not deter readers looking for deep exploration of Bonhoeffer’s life. It’s essentially an extended essay on writing Strange Glory, writing biographies generally, how to evaluate the accuracy and impact of history, and, most extensively, a response to another Bonhoeffer scholar’s persistent critiques of Marsh’s biography. That other scholar is Ferdinand Schlingensiepen, whose own biography of Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Bonhoeffer 1906-1945: Martyr, Thinker, Man of Resistance remains a book I recommend to readers as well. But Schlingensiepen took great issue with Marsh’s exploratory directions in the latter’s life of Bonhoeffer, ultimately going a bit off the rails at points, not just criticizing Marsh for the kind of small mistakes all biographers make (eg. geographical, a few temporal, etc.) but also arguing that Marsh’s biography is entirely useless because it doesn’t focus on Schlingensiepen’s own preferred trajectory of reading Bonhoeffer.

Specifically, Schlingensiepen takes a nearly obsessive interest in critiquing Marsh for not focusing on minutiae of the church struggle in Germany and upbraids him for not following Bethge’s biography of Bonhoeffer more closely. Marsh, in turn, notes the errors with such a critique, both for pigeonholing Bonhoeffer’s own life into less impactful and radical than it was and in failing to allow for new avenues of research into Bonhoeffer. It appears that, for Schlingensiepen, the Confessing Church must be entirely without error, while narratives of Bonhoeffer’s life must never depart from prior research.

Marsh effectively answers Schlingensiepen’s critiques time and again, all while pushing for a resistance to a kind of “Bonhoeffer Brand” that would limit exploration of his life and theology to only that which is approved or has been done before.

Resisting the Bonhoeffer Brand is a book I would consider essential reading for those interested in studying Dietrich Bonhoeffer. It also is a great look at the challenges and delights of writing biographies more generally. Highly recommended.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

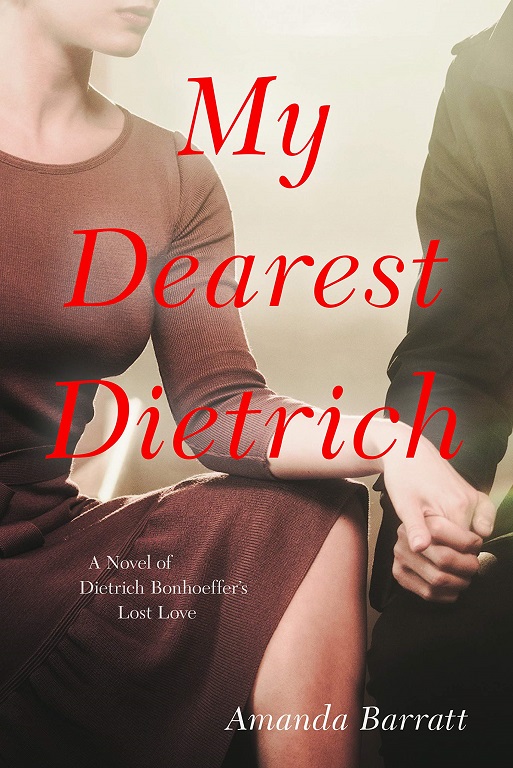

Bonhoeffer’s Life in Fiction- Critical Review of “My Dearest Dietrich: A Novel of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Lost Love” by Amanda Barratt

Amanda Barratt offers an historical novel based on the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer with My Dearest Dietrich. As the subtitle states, it is “A Novel of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Lost Love.” Specifically, Barratt delves into Bonhoeffer’s letters and writings and builds a narrative around them focused on his relationship with Maria von Wedemeyer.

Barratt does a fine job of weaving that narrative around Bonhoeffer’s letters. I wouldn’t consider myself an expert on Bonhoeffer, but having read many books about him as well as his collected works, the narrative seems to at least largely follow the course of his life. Bonhoeffer’s close relationship with Ruth von Kleist-Retzow, Maria’s grandmother, is highlighted. Interestingly, Bonhoeffer’s first meeting with Maria is only presented in the briefest type of flashbacks. Historically, Maria’s grandmother had tried to get Bonhoeffer to accept Maria into his confirmation class, but he refused after seeing her as “too immature” to do so. In the novel, she’s upset about having embarrassed herself in front of him some years before.

In a sense, My Dearest Dietrich is a reframing of Bonhoeffer’s life. Essentially, Barratt turns many of his encounters with Maria or others into a kind of building of and reflecting upon growing love in order to make the plot work. However, much of this is done inside Bonhoeffer’s head rather than being drawn from historical documents. This is, of course, the way historical novels must work. Barratt’s goal of showing Bonhoeffer’s growing relationship and love for Maria requires this kind of internal monologue throughout in order to make sense. Thus, it has to be invented for the sake of the story.

Those who have studied Bonhoeffer extensively know that there is some question about his sexuality and more specifically his relationship with Eberhard Bethge. The most thorough look at these questions may be found in The Doubled Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer by Diane Reynolds. Reynolds argues extensively that Bonhoeffer was in love with Bethge. Moreover, she argues that Bonhoeffer’s relationship with Maria von Wedemeyer was a kind of cover as his imprisonment loomed. His relationship with the much younger Maria would solidify him as a “masculine” German–something emphasized in Nazi propaganda–while also providing a cover for any hints of homosexuality. Gay people were one of the oppressed classes of the Nazis who were rounded up and murdered by them (homosexuality remained outlawed in Germany for sometime after, as well). Thus, Maria would serve as a kind of double cover for any questions about Bonhoeffer’s conforming to cultural expectations.

Reynolds’s book presents a strong, thoughtful argument with which any scholarship related to Bonhoeffer must contend (see my full review of the book here). Barratt’s novel ignores that and essentially offers a counter-narrative in which Bonhoeffer is struck almost immediately by the thoughtfulness of young Maria and eventually comes to fall in love with her and get engaged with the intent to marry. For Barratt, none of these questions about sexuality arise. The absence of Bonhoeffer’s growing love and thoughts of love in some of his other works is explained largely through having no time to reflect upon it and actively resisting reflecting on it because he believed, in Barratt’s account, that other things were more important.

My Dearest Dietrich, then, is not just a novel about Bonhoeffer’s life. It is a retelling of the events and framing them in a way that cuts away some of the more intriguing questions about his sexuality and love for Maria. Bonhoeffer’s relationship to Maria, and the age difference between them (he was her senior by 18 years) has perplexed some Bonhoeffer scholars. Reynolds’s exploration helps make sense of some of these questions. Indeed, even setting aside his sexuality, simply offering the explanation that he saw Maria as a way to show his German virility to the Nazi interrogators is plausible enough.

What one makes of My Dearest Dietrich, then, is what one may. Barratt’s clear influence from Eric Metaxas’s pseudo-biography of Bonhoeffer is found in her acknowledgements, where she makes it clear that she was most influenced by that work. Metaxas’s biography, however, is largely ignored or rejected by broader Bonhoeffer scholarship due to its transformation of Bonhoeffer into a character of Metaxas’s own choosing. That Barratt was so deeply influenced by this biography and then wrote a novel of Bonhoeffer’s life with virtually no reference to any of the possible controversies it may raise is an interesting detail.

Barratt does make a compelling narrative, though, and one which, if she’s right about Bonhoeffer’s relationship, does a good job explaining those historical anomalies she does acknowledge. For example, Maria’s constant theme of doubting Bonhoeffer’s love is partially balanced by Bonhoeffer actively resisting the same for the sake of what he sees in the novel as his more important work of resistance. If Barratt’s view of Bonhoeffer’s love and sexuality (again, the latter being wholly ignored as a topic here) are correct, then her novel at least offers a way to make more sense of it all.

My Dearest Dietrich, then, is not merely an historical fiction. Rather, it is a kind of apologetic for one vision of Bonhoeffer. One that stretches the man in ways that go beyond the historical record, his own writings, and perhaps even the deepest parts of his character. As Stephen R. Haynes put it, the “battle for Bonhoeffer” continues. This novelization of his life is another battle front offering an alternate narrative of the man’s life and legacy.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Pacifism, Just War, and Tyrannicide: Bonhoeffer’s Church-World Theology and His Changing Forms of Political Thinking and Involvement” by David M. Gides

The question of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s view on subjects related to war: Just War, Pacifism, Tyrranicide, and related issues is one that is hotly contested in Bonhoeffer scholarship. David M. Gides’s Pacifism, Just War, and Tyrranicide: Bonhoeffer’s Church-World Theology and His Changing Forms of Political Thinking and Involvement makes the case that Bonhoeffer did not experience a unity of thought on the subject and instead changed over time. Gides argues that Bonhoeffer ultimately developed a church-world theology that went beyond a conservative Lutheran Two Kingdoms position as well as against a time in his life in which he held to pacifism.

The question of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s view on subjects related to war: Just War, Pacifism, Tyrranicide, and related issues is one that is hotly contested in Bonhoeffer scholarship. David M. Gides’s Pacifism, Just War, and Tyrranicide: Bonhoeffer’s Church-World Theology and His Changing Forms of Political Thinking and Involvement makes the case that Bonhoeffer did not experience a unity of thought on the subject and instead changed over time. Gides argues that Bonhoeffer ultimately developed a church-world theology that went beyond a conservative Lutheran Two Kingdoms position as well as against a time in his life in which he held to pacifism.

Gides separates Bonhoeffer’s thought on church-world relations into four phases, in contrast with what he says is the majority opinion that separates his thought into three stages. These phases are the church and world in mild tension, the church and world in heightened tension, the church against or apart from the world, and the church as the world. Gides argues that, too often, interpreters of Bonhoeffer’s thought have taken quotes from different parts of his life in order to try to form a cohesive picture, when instead Bonhoeffer’s thought had significant development through these phases (xii-xiii).

In the earliest phase, Bonhoeffer was decidedly not a pacifist and saw violence as potentially being sanctified through certain actions like laying down one’s life for the neighbor or to take up arms to defend the Volk (folk = the nation/people) (112-114). Gides argues this earliest statement and those like it were driven by a conservative or traditional Lutheran understanding of the Two Kingdoms theology which allowed for this lack of engagement with the state by Christians. Heightened tension in the world led Bonhoeffer to back off these early statements. Later in his life, Bonhoeffer felt a drive for ecumenism and pacifism, but this movement included engagement in the world directly. Here we see Bonhoeffer’s three stages of church-state engagement: questioning the state’s actions, providing service to victims of the state, and ultimately seizing the wheel itself from the state (also known as the famous “drive a spoke through the wheel” statement) to direct it away from evil (185). Later, Bonhoeffer makes some extremely strong statements about peace, including a powerful statement about the differences between peace and security. These show that he had moved into a pacifistic view, but his pacifism in this phase of his life, according to Gides, was one that separated the church from the state almost entirely, to the point where the church had to move away from or against the state (220-224; 230ff; see also his discussion of Discipleship in this context). Finally, Gides argues Bonhoeffer developed a church-world theology that allowed for direct action in which the church is the world and tyrannicide is possible. This phase included Bonhoeffer’s own involvement in the Abwehr and in part of a plot to kill Hitler (328-332).

Gides’s work is challenging and well-thought out. He presents serious challenges for several views, especially those that argue that Bonhoeffer remained explicitly pacifist (or that he was pacifistic throughout his life) as well as views that see Bonhoeffer’s thought as entirely cohesive. It does seem clear that Bonhoeffer’s thought developed on these questions, particularly comparing his pacifistic stage (phase 3) to his earliest thoughts on peace and war (phase 1).

There are some challenges to Gides’s theses, as well. One is the challenge offered by a minority of Bonhoeffer scholars that Bonhoeffer was not involved in the plot to kill Hitler at all (eg. in Bonhoeffer the Assassin?). Gides’s work was written before this other work, so it’s difficult to know what his defense would be, but it seems Gides would answer that Bonhoeffer does seem to be clearly involved in this plot, or at least, minimally, in actions that set him against the state in ways that could lead to such plots. That alone would undermine a fully pacifist view. Gides does acknowledge the diversity of pacifistic views (too often, pacifism is seen as a unified thought), and it would be interesting to see a full engagement with his work from the side of a pacifist developing a view from Bonhoeffer’s thought. It does seem to me Bonhoeffer made contributions to pacifistic thought, but that he could not be included in any pacifist position that holds to absolute non-violence.

Another challenge is that of Lutheran Two Kingdoms theology itself. Gides mentions this theology at multiple points in the work, but doesn’t do much legwork to define how he’s using it. Most often, Gides uses it alongside the word “conservative,” making it a narrower referent than the broader notion of Two Kingdoms thinking. Specifically, Gides seems to denote by “Two Kingdoms” the later developed Lutheran position that held to a kind of pseudo separation of church and state that enabled many in Germany to simply look the other way with what the secular authorities were doing, thus excusing or even participating in atrocities. However, such a theory of Two Kingdoms is one that, while “conservative” in the sense of being what seemed to be the traditional view in Germany at the time of Bonhoeffer’s life, does not fully show the breadth of thought on the Two Kingdoms theology of Luther. Indeed, Gides’s view of Bonhoeffer’s final position seems to be one that may actually be more fully in line with Luther’s Two Kingdoms theology than was the “conservative” position of the same during his life (see, for example, DeJonge’s Bonhoeffer’s Reception of Luther). In fact, one could make the argument that we could read Bonhoeffer cohesively within the bounds of Lutheran Two Kingdoms thought. Thus, Gides’s phases would be different interpretations of the Two Kingdoms theology, and the final phase especially may be closest to Luther’s own thinking on the topic. His phases in thought could then be seen to be sliding along the possible interpretations of Two Kingdoms theology. Gides does make the distinction that he is speaking of this “conservative” Two Kingdoms thought, but when he stresses that Bonhoeffer apparently rejected Two Kingdoms thinking, I believe he goes too far, because it seems more accurate to say that Bonhoeffer’s ultimate church-world theology was that of a fully realized Two Kingdoms.

Gides’s Pacifism, Just War, and Tyrranicide is a thoughtful reflection and interpretation of Bonhoeffer’s theology of church-world relations. His unique division of Bonhoeffer’s thought is reason for reflection, while his ultimate thesis will surely spark debate among those interested in Bonhoeffer’s theology. More importantly, he provides a way forward in reading Bonhoeffer’s ultimate theology, though not one that sees it as cohesive throughout his life.

Disclaimer: I was provided with a copy of the book for review by the publisher. I was not required to give any specific kind of feedback whatsoever.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read more posts I’ve written on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s life and thought. There are also several Bonoheffer-specific book reviews here.

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “The Battle for Bonhoeffer” by Stephen R. Haynes

The Battle for Bonhoeffer by Stephen R. Haynes highlights the ways that people across theological, social, and political spectrums have played tug-of-war with Bonhoeffer’s thought, words, and legacy. As Charles Marsh puts it in his Foreword, “It is understandable… that readers with different theological and ideological perspectives would desire to claim Bonhoeffer as their own. ‘Excerpting Bonhoeffer’ has become a familiar exercise in each team’s effort to win…” (ix). Yet Bonhoeffer’s legacy is far more complex than a simple Google quote mine would allow. In my own reading of Bonhoeffer’s works, it is clear that it would be simple to find conflicting messages even within the same sermons at times. Like Martin Luther, for example, reading Bonhoeffer and interpreting him is like peeling away the layers of an onion, trying to get to the core. It takes care, precision, and thought. Unfortunately, as Haynes notes throughout this book, few people are concerned with doing so.

The Battle for Bonhoeffer by Stephen R. Haynes highlights the ways that people across theological, social, and political spectrums have played tug-of-war with Bonhoeffer’s thought, words, and legacy. As Charles Marsh puts it in his Foreword, “It is understandable… that readers with different theological and ideological perspectives would desire to claim Bonhoeffer as their own. ‘Excerpting Bonhoeffer’ has become a familiar exercise in each team’s effort to win…” (ix). Yet Bonhoeffer’s legacy is far more complex than a simple Google quote mine would allow. In my own reading of Bonhoeffer’s works, it is clear that it would be simple to find conflicting messages even within the same sermons at times. Like Martin Luther, for example, reading Bonhoeffer and interpreting him is like peeling away the layers of an onion, trying to get to the core. It takes care, precision, and thought. Unfortunately, as Haynes notes throughout this book, few people are concerned with doing so.

Though the subtitle is “Debating Discipleship in the Age of Trump,” there is far more to the book than dealing with the recent Trump phenomenon. Haynes notes how people on both the right and left have distorted or ignored aspects of Bonhoeffer’s legacy to turn in him into a supporter of their own positions. Marsh sets the table well, asking: “Have you heard progressive Christians cite the passage in Ethics calling abortion ‘nothing but murder’? Or recall Bonhoeffer’s preference for monarchy over democracy?” (xii). Haynes notes how Bonhoeffer was cited on one hand by Vietnam draft resisters, peace activists, liberation theologians, death-of-God thinkers on the left, and on the right by people who oppose abortion or same-sex marriage (and, regarding the latter, Haynes notes insights from both Charles Marsh’s Strange Glory and Diane Reynolds The Doubled Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer [which I reviewed here] for reasons this may be quite inaccurate]). The baffling array of topics Bonhoeffer is alleged to have endorsed or condemned suggests that the quote mining being done through his legacy belies an inner complexity that is far deeper.

Haynes surveys the history of interpretation of Bonhoeffer, particularly in America, through the next several chapters. He places a special emphasis on seeing how evangelicals have viewed Dietrich Bonhoeffer. What is interesting in this latter topic is that, initially at least, Bonhoeffer was viewed positively but with some “warning flags” by American evangelicals who interacted with his works. Several appreciated his resistance to Nazi ideals, but were put off by his apparent lack of concern for things like “a high view of Scripture/inerrancy” and his being influenced by liberal German theologians. This portrait by the early evangelicals of Bonhoeffer is far more accurate than the one that has been passed into our own time, in part because it allowed for a multifaceted Bonhoeffer who was complex enough to resist being easily integrated into any one position.

Fairly early on, however, the complexities of Bonhoeffer’s thought and life began to be ignored in favor of seeing him as a figurehead for resistance to one’s own preferred ideas. Haynes demonstrates how Bonhoeffer was used to resist George W. Bush and the “war on terror,” and then ironically turned around to resist the “culture of death” under Barack Obama. The raising of the “Bonhoeffer flag” behind such opposed viewpoints should have served as a warning sign, but it unfortunately did not.

Enter Eric Metaxas. Metaxas’s biography, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy was an extreme departure from Bonhoeffer scholarship generally. For one thing, Metaxas himself admitted to virtually ignoring or explicitly shunning the conclusions of 70 years of Bonhoeffer scholarship both at home and abroad. The cover flap for the book features a spurious quote from Bonhoeffer “Silence in the face of evil is evil itself…” that has since been passed all over the world and even “quoted” multiple times in Congress on record. To say that using an invented quote from Bonhoeffer on the cover of a biography of the man is a bad sign is an understatement. Haynes notes many, many problems with the biography, from a lack of engagement with Bonhoeffer’s actual works (and ignoring, for example, his Letters and Papers from Prison, which is one of the most important works for understanding his developed thought) to a recasting of Bonhoeffer into an American Evangelical. Yet it is Metaxas’s biography that has become the torch-bearer for the populist Bonhoeffer, making an image of the man that is incredibly distorted. For my own part, when I read Metaxas’s work, I was struck by how entirely de-Lutheranized Metaxas had made Bonhoeffer. Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a man who explicitly stated that, for example, without the Lord’s Supper there is no Christianity and who certainly supported infant baptism and regeneration, but Metaxas excised such details from his own dim look at Bonhoeffer’s theology, preferring to pull out those things which were more amenable to the typical American evangelical.

It was the populist view of Bonhoeffer which lead to notions of a “Bonhoeffer Moment” at various times before, during, and after the 2016 election cycle. Haynes spends some time noting how it was frequently said during the Obergefell v. Hodges Supreme Court case that American Christians were facing a “Bonhoeffer Moment” in which they would need to resist the government’s tyranny. Haynes notes how many evangelicals made comparisons to previous Supreme Court rulings, conveniently ignoring those unjust rulings they supported or the just ones they opposed. More decisively, Haynes notes that after Obergefell, evangelicals rallied around a woman who was part of an anti-Trinitarian sect to be their martyr for the cause. In the time since, though, very little has been done by evangelicals in their supposed “Bonhoeffer Moment.” This kind of co-option of the man’s legacy is a disservice to all involved.

Haynes doesn’t limit his analysis of the “battle for Bonhoeffer” to just the positives of Bonhoeffer’s life. Metaxas and others have argued Bonhoeffer is a “Righteous Gentile” (Metaxas even made “righteous gentile” part of his additional subtitle to his biography). But Bonhoeffer has explicitly been turned down for that technical categorization for a few reasons: 1) he wrote or supported some things that were seemingly anti-Semitic; and 2) though he did become a martyr, it wasn’t specifically due to his efforts to help the Jews during the Holocaust, which is a criterion for being deemed a “Righteous Gentile.” Bonhoeffer certainly opposed the Nazi treatment of the Jews and did help some Jews escape Germany (though at arm’s length for the most part–simply helping get proper papers from afar); but that was not his project or his main reason for opposing Nazi Germany. And that’s okay. It is important not to lionize Bonhoeffer for things he didn’t actually do, and Haynes is careful to help readers realize that.

The Battle for Bonhoeffer isn’t very long, but its length shouldn’t be taken for a lack of depth. It’s a thoughtful, critical, and sometimes convicting read. As one who is deeply indebted to Dietrich Bonhoeffer in my own theology and thought, I found ways in which I had been distorting him in this book as well. Haynes’ book provides an invaluable correction to distortions on the man’s life, times, and thought. I very highly recommend it.

Disclaimer: I was provided with a copy of the book for review by the publisher. I was not required to give any specific kind of feedback whatsoever.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Bonhoeffer As Reliable Guide?

I seem to have made it something of a pastime explaining to others things about Lutheran belief, and often this pertains to discussions of Bonhoeffer. Almost everyone is trying to make Bonhoeffer in their own image. Whether it is the notion of calling Bonhoeffer an evangelical, or recruiting him to various other schools of thought, Bonhoeffer is enduring a kind of celebrity right now. That celebrity comes with its share of difficulties, including pushback. Some evangelicals have labeled Bonhoeffer dangerous. A recent article by William Macleod questions whether Dietrich Bonhoeffer may be a “reliable guide” when it comes to Christianity: Bonhoeffer – A Reliable Guide? That blog post levels a number of criticisms at the Lutheran theologian, and I would like to respond to this article, which I think misrepresents Bonhoeffer in many ways. I’ll not respond to every point, because Macleod overlaps points I’ve responded to before.

I seem to have made it something of a pastime explaining to others things about Lutheran belief, and often this pertains to discussions of Bonhoeffer. Almost everyone is trying to make Bonhoeffer in their own image. Whether it is the notion of calling Bonhoeffer an evangelical, or recruiting him to various other schools of thought, Bonhoeffer is enduring a kind of celebrity right now. That celebrity comes with its share of difficulties, including pushback. Some evangelicals have labeled Bonhoeffer dangerous. A recent article by William Macleod questions whether Dietrich Bonhoeffer may be a “reliable guide” when it comes to Christianity: Bonhoeffer – A Reliable Guide? That blog post levels a number of criticisms at the Lutheran theologian, and I would like to respond to this article, which I think misrepresents Bonhoeffer in many ways. I’ll not respond to every point, because Macleod overlaps points I’ve responded to before.

Methodological Notes

At the outset, I must point out a major problem with the article is that there is a distinct lack of citation throughout. Indeed, the only footnote is a reference to an article about Bonhoeffer, not a reference to Bonhoeffer’s works at all. Moreover, though many assertions are made about what Bonhoeffer wrote–as well as a few quotations–no references are provided, which makes it at many points impossible to easily track down the reference and so provide a full response. It is disturbing to me to see such lack of citation in an article that purports to correct evangelical thought on this theologian. How are we to evaluate an article that makes it difficult to even double-check the facts?

Second, Macleod does not define evangelical in this article, or provide a clear reference to what he means. Because there is great difficulty with the definition of “evangelical” in its modern and historical usage. Indeed, Bonhoeffer’s German Lutheran church historically simply referred to itself as evangelical–a tradition carried on to this day in my church body, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. The problem is that the term “evangelical” often means different things to different people, a problem acknowledged in many circles. The article would have been helped had Macleod provided exactly his meaning of evangelical to compare his statements to.

Bonhoeffer as Liberal Theologian?

Macleod alleges, “Far from being an evangelical, Bonhoeffer was more liberal than Barth. He considered himself a ‘modern theologian who still carries the heritage of liberal theology within himself’.” Here we already see a difficulty with the methodology–where is this quote from Bonhoeffer to be found? A search online turned up other blog posts that give this same quote, but this one, for example, writes a citation [5] in brackets but then there is no referent for [5]. I finally managed to possibly track down a reference on a different article, but don’t have the book in front of me at this point so I can’t confirm it. However, even granting he said that, I’d love to see the context. After all, he could have been saying it in the sense of saying that he has been influenced by liberal theology, which was certainly found all around him in Germany. But of course Bonhoeffer himself, at the end of his life, explicitly argued against liberal theology at multiple points.

Bultmann seems to have somehow found Barth’s limitations, but he misconstrues them in the sense of liberal theology, and so goes off into the typical liberal process of reduction – the ‘mythological’ elements of Christianity are dropped… My view is that the full content, including the ‘mythological’ concepts, must be kept… this mythology (resurrection etc.) is the thing itself… (Bonhoeffer, Letters and Papers from Prison, 328-329)

Those are Bonhoeffer’s words, written in 1944 from prison. Does that look like an acceptance of liberal theology? Bonhoeffer does engage liberal theologians, of that there is no doubt, but he explicitly notes the deficiencies of their theology and argues the opposite position. Macleod’s attempt to poison the well here fails.

Bonhoeffer as Martyr

Macleod, amusingly, questions whether Bonhoeffer was a martyr:

When we think of Christian martyrs we think of the early Christians thrown to the lions for refusing to worship Caesar. We think of Reformers like Patrick Hamilton and William Tyndale burnt at the stake for preaching the gospel and for translating the Scriptures into the language of the people. In no sense were these men involved in conspiracies against the state. Bonhoeffer died for being involved in a plot to assassinate Hitler… his death was not because of his beliefs, but rather for his ‘crime’ of conspiracy to murder.

I actually found myself chuckling here. I don’t know Macleod, and I know nothing about him. What I do know, and have seen many times, is a lack of understanding of church history among those broadly identifying themselves as evangelicals (I’m not the only one who bemoans this, on a different end of the spectrum than me stands James White, who I’ve heard on his podcast multiple times speak of the lack of knowledge of church history in evangelical circles). I preface that remark because Macleod’s comment about martyrs shows a bit of ignorance. If he wants to say Bonhoeffer’s not a martyr because he died for political reasons, perhaps he should go back and see that the worship of Caesar for which Christians were killed was, itself, a political killing. Virtually every book I’ve ever read on this early period of Christianity confirms this. For just one reference, check out the interplay between pagan and Christian apologists found in Apologetics in the Roman Empire.

Moreover, Macleod’s comment is amusing because the separation of belief from action is a very modernist/postmodernist separation, and one that could just as easily be used to say “the early Christian martyrs weren’t killed for their beliefs, they were killed for refusing to worship Caesar, a political act.” But of course that refusal is based on belief, just as Bonhoeffer’s ethical stance regarding Hitler was based on belief. Belief put into practice remains belief. The attempt to tarnish Bonhoeffer’s legacy as, yes, Christian martyr here bespeaks both lack of historical awareness and the overall tone of the article.

The Cross

Macleod accuses Bonhoeffer of decentralizing the cross because, according to Macleod, he did not believe in substitutionary atonement. More damningly, Macleod charges Bonhoeffer with seeing the cross as “an example and an inspiration.” I was astonished to read this from Macleod. Aside from the fact that Bonhoeffer wrote an entire book about Jesus Christ being the center not just of our faith but as the center of human history (Christ the Center, 59ff), he also repeatedly emphasized this in his other writings. Macleod stated, “For evangelicals the cross is at the centre of their faith.” I’m not at all sure why he thinks he should disagree with Bonhoeffer here, unless he just hasn’t read Bonhoeffer’s body of work.

Conversion

I’ve responded to this elsewhere, but Macleod’s words about conversion regarding Bonhoeffer are deeply troubling to me:

As a Lutheran he embraced the doctrine of baptismal regeneration – you are automatically born again when you are baptised. Around 1931 Bonhoeffer experienced a ‘conversion’, when he, as he puts it, discovered the Bible… Yet it was not what evangelicals normally call conversion, or what the Scriptures describe as the new birth. He rarely referred to it… He wrote, ‘We must finally break away from the idea that the gospel deals with the salvation of an individual’s soul’.

A number of things are problematic here. First, Macleod blatantly misrepresented the Lutheran view of baptismal regeneration by couching it in terms borrowed from Baptist theology. Baptismal regeneration is not about “automatically” being born again; it is about the gift of God that has been promised through baptism, even to infants. I’m not going to debate this rather obvious point here, but the fact that Macleod effectively dismisses Bonhoeffer simply because he’s Lutheran says something disturbing about his view of what it takes to be evangelical–apparently a view that excludes Lutherans entirely.

Moreover, Macleod once again conforms to modern American evangelicalism (not even sure if he’s from the United States, but the ideas he has are) by emphasizing the individual over the community. Any number of theologians have shown time and again that the evangelical focus on individual salvation is something born, historically, from a rather American emphasis on the individual rather than being something directly derived from Scripture. Not saying that individual salvation is not there, but as the primary theme? N.T. Wright, among others, has done some correction in this regard, and Bonhoeffer himself did in works like Life Together.

Universalist Bonhoeffer?

Macleod writes:

Bonhoeffer was a universalist, believing in the eventual salvation of all. He wrote that there is no part of the world, no matter how godless, which is not accepted by God and reconciled with God in Jesus Christ. Whoever looks on the body of Jesus Christ in faith can no longer speak of the world as if it were lost, as if it were separated from Christ. Every individual will eventually be saved in Christ.

There’s no citation here, or even a quote, so it is very hard to track down what he is referencing in Bonhoeffer’s writings. Of course, what he’s written here is not universalism, but rather a denial of limited atonement and, actually, the Lutheran view of incarnation. Luther himself emphasized that Christ is present in all of creation. With the incarnation, God is present with us. Macleod, again, doesn’t give a reference to track down, but based on the rest of the article I think he is just misunderstanding Bonhoeffer again. The Lutheran perspective denies limited atonement, and whether that is correct are not is hardly a specific accusation against Bonhoeffer. Of course, without a citation, all we can do is trust Macleod not to have misrepresented Bonhoeffer–something that, at this point, I’m unwilling to do. I haven’t read everything Bonhoeffer wrote, though I’ve read about 75% of his collected works at this point, and some of his books twice, and I don’t know of any reference that could be shown to be universalism explicitly rather than a denial of limited atonement. I await a citation.

Sabbath

Macleod again reveals how much he is reliant upon his presuppositions when he writes:

The Sabbath was given to man at creation. The command to keep the one day in seven holy was reiterated on Mount Sinai and written with the finger of God on tables of stone. Jesus kept the Sabbath and said that the Son of man is Lord of the Sabbath. Bonhoeffer, however, is quite happy to play table tennis on Sunday or to attend the theatre.

So, again, we have Bonhoeffer critiqued for being Lutheran. This is a pretty clear example of Macleod showing his stripes. It’s not so much Bonhoeffer that’s the problem; it is anyone who isn’t some kind of Reformed Baptist that’s the problem. Bonhoeffer was just a convenient target because people know who he is. Besides all that, Macleod’s words show very clearly that according to him, humans were made for Sabbath, not the other way around. But of course that makes gospel into law–and the proper distinction of law and Gospel is one of the central teachings of Lutheranism. But again, this is a debate for a different place. It’s fair enough to point out that Macleod’s argument here relies on a very specific presupposition, one that certainly not all evangelicals share, let alone Lutherans.

Conclusion

I have already written about twice as much as I meant to, and more could be said. It is clear that Macleod’s article is little more than a hit piece. There are no explicit citations to Bonhoeffer’s works (even when he is directly quoted, allegedly!), Macleod constantly condemns Bonhoeffer for clearly Lutheran views, and the whole article is based upon Macleod’s theological convictions, many of which I doubt he could demonstrate all evangelicals share. The pot shot at Bonhoeffer alleging he’s not a martyr shows the overall attitude Macleod has towards those he disagrees with, but it also–like many other points in the post–demonstrates a lack of historical awareness that pervades much of the church. Perhaps we can use his article in one positive way: rather than as a warning against Bonhoeffer–a faith-filled, Lutheran, courageous–yes–martyr–we can see it as a warning of the dangers of not taking history seriously.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Bonhoeffer’s Troubling Theology?- A response to an article on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theological perspectives– I respond to a different article on Dietrich Bonhoeffer. We again see numerous misrepresentations and misunderstandings of Bonhoeffer and Lutheranism.

Eclectic Theist– Check out my other blog for my writings on science fiction, history, fantasy movies, and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Bonhoeffer Speaks Today” by Mark Devine

Mark Devine’s Bonhoeffer Speaks Today is a pithy summary of the doctrines of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and how they might be applicable now.

Mark Devine’s Bonhoeffer Speaks Today is a pithy summary of the doctrines of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and how they might be applicable now.

The book is organized around chapters that each focus on how Bonhoeffer’s thought might be applied to today. Within each chapter are sub-headings, sometimes as short as one paragraph, that look at specific aspects of his works or life to apply them now. The brevity of the book is one of its strengths. Often, stirring insights can be found in a section no longer than a few sentences. I think this shows both the depth and intricacy of Bonhoeffer’s own thought as well as the way Devine has arranged the book to highlight them.

There are two areas I’d like to critique in regards to the book. The first is that Bonhoeffer’s clear Lutheranism is ignored. Dietrich Bonhoeffer is clearly a Lutheran through-and-through with a commitment to orthodox Lutheran understanding of Baptism and the Lord’s Supper. To write of Bonhoeffer speaking today without incorporating his sacramental understanding which is so integral to his theology is to take away from Bonhoeffer much of his voice. The second criticism is that the language used throughout the book continues to use the archaic “man” to refer to “men and women” as well as other gendered language when it would be just as simple to make the language inclusive.

Bonhoeffer Speaks Today is full of practical theology from the writings of one of the most engaging theologians of the 19th Century. If you’re looking for an introduction to his thought, this is a good place to start. However, be aware that a central aspect of Bonhoeffer–his Lutheranism–is notably absent.

The Good

+Excellent brief introduction to Bonhoeffer’s life and context

+Filled with juicy quotations

+Many, many digestable insights

The Bad

-Does not use gender inclusive language

-No mention of Bonhoeffer’s Lutheranism

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Bonhoeffer’s Troubling Theology?- A response to an article on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theological perspectives– I look at an argument that Bonhoeffer’s theology is “troubling” to evangelicals and point out how much of it is merely a product of his Lutheran background.

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

Eclectic Theist– Check out my other blog for my writings on science fiction, history, fantasy movies, and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Really Recommended Posts 8/23/13- Twain, Egypt, creationism, and more!

I am excited to offer you, dear reader, a slew of fantastic posts for your perusal. The topics this go-round are diverse. We will look at Egypt and the media coverage there, Mark Twain and the Book of Mormon, Darwin’s Doubt, creationism, Stephen King’s Under the Dome, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

I am excited to offer you, dear reader, a slew of fantastic posts for your perusal. The topics this go-round are diverse. We will look at Egypt and the media coverage there, Mark Twain and the Book of Mormon, Darwin’s Doubt, creationism, Stephen King’s Under the Dome, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Mainstream media silent as Muslim Brotherhood targets Christians in Egypt– What is going on in Egypt? Violence against Christians has boiled over, but it seems we hear nothing about it here. Check out this article to read a refreshing perspective which will help inform you about what’s going on “over there.”

Mark Twain’s Review of the Book of Mormon– Mark Twain was a hilarious satirist and well deserves his place among the top American writers of his time. In this post, he turns his humorous pen to the Book of Mormon. It is worth noting a few errors with Twain’s account, however. I’m not sure if the Mormon account has changed, but Twain writes that the Book of Mormon was alleged to be translated from copper plates, when it is said to have been gold. More interestingly, Twain reveals his grounding in his own times when he writes “The Mormon Bible is rather stupid and tiresome to read, but there is nothing vicious in its teachings. Its code of morals is unobjectionable—it is ‘smouched’ from the New Testament and no credit given.” Take a gander at 2 Nephi 5:21ff (scroll down to verse 21 and following) and let me know if you see something which is similar to the New Testament’s statement in Galatians 3:28 and whether you object to the Book of Mormon’s writing in 2 Nephi.

Science, Reason, & Faith: Evaluation of Darwin’s Doubt by Stephen C. Meyer, part 1– With shouts of “pseudo-science” clamoring to drown out those who are even attempting to do research in the area of intelligent design, it is refreshing to sit back and look through some analyses which interact with the works rather than just spewing vitriol. I found this series of posts quite interesting and worth the read as I have been reading through the book myself.

Upset Creationist– Jay Wile is a young earth creationist whom I respect. His integrity is admirable. I disagree with his position strongly, but I admire him as person of character. This post is no different. He interacts with some comments the well-known creationist Ken Ham directed his way. Perhaps most thought-provoking was Wile’s comment that “Whether we are talking about the materials from Answers in Genesis or that particular exhibit in the museum, the message is crystal clear: the concept of millions of years has destroyed the church. I strongly disagree with that message.” Wile’s acknowledgement that we can be brothers and sisters in Christ despite disagreeing on this issue is refreshing.

Stephen King’s “Under the Dome”: A Mid-Season Perspective– one of my favorite blogs, Empires and Mangers, takes a look at the TV series based on the horror author’s work, “Under the Dome.”

Bonhoeffer, the Church, and the Consequence of Ideas– I’m a huge fan of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s work. For those who don’t know, Bonhoeffer was a Lutheran who was executed by the Nazis during World War 2. In this article, his view of the Church and how that influenced his activism is briefly explored.