Lutheran theology

“Only a Suffering God can help” – Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Theologia Crucis

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology is heavily based upon the Theologia Crucis or the Theology of the Cross which he inherited from Martin Luther. H. Gaylon Barker’s The Cross of Reality is a book-length exposition of this important aspect of Bonhoeffer’s theology that brings an enormous amount of material and analysis to bear.

Barker’s analysis of Bonhoeffer’s theology of the cross is worth quoting at length:

“One problem… religion produces , from Bonhoeffer’s perspective, is that it plays on human weakness. In the world in which people live out their lives… this means a disjuncture or contradiction. Daily people rely on their strengths, in which they don’t need God. In practical terms, therefore, God is pushed to the margins, turned to only as a ‘stop-gap’ when other sources have given out. Then God, perceived as a deus ex machina, is brought in to rescue people. This, in turn, leads to the religious conception of God and religion in general as being only partially necessary; they are not essential, but peripheral. All of this leads to intellectual dishonesty, which is not so unlike luther’s description of the theology of glory. The strength of the theology of the cross, on the other hand, is that it calls a thing what it is. It is honest about both God and the world, thereby enabling one to live in the world without seeking recourse in heavenly or escapist realigous practices. Additionally, such religious thinking leads to the creation of a God to suit human needs… For Bonhoeffer and Luther, however, the real God is one who doesn’t appear only in the form we might expect, one whom we can incorporate into our worldview or lifestyle. God is one who is always beyond our grasp, but at the same time is a hidden presence in the world” (394).

Barker highlights Bonhoeffer’s own words to make this point extremely clear:

“[W]e have to live in the world… [O]ur coming of age leads us to a truer recognition of our situation before God. God would have us know that we must live as those who manage their lives without God. The same God who is with us is the God who forsakes us (Mark 15:34! [“And at three in the afternoon Jesus cried out in a loud voice, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?‘ (which means ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’)”]). The same God who makes us to live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God, and with God, we live without God. God consents to be pushed out of the world and onto the cross; God is weak and powerless in the world and in precisely this way, and only so, is at our side and helps us. Matt. 8:17 [“This was to fulfill what was spoken through the prophet Isaiah: ‘He took up our infirmities and bore our diseases.’] makes it quite clear that Christ helps us not by virtue of his omnipotence but rather by virtue of his weakness and suffering!” [388, quoted from DBWE 8:478-479]

Thus, for Bonhoeffer, God is not there as the divine vending machine, there to send out blessings when needed or called upon due to human inability. Instead, God enters into the world and by suffering, alongside us, helps us.

Bonhoeffer put it thus: “Only a suffering God can help.” Bonhoeffer, seeing the world as it was in his time, during the reign of terror of the Nazis, imprisoned, knew and saw the evils of humanity. And he knew that in seeing this, theodicy would fail. A God who worked only through omnipotence and only where human capacities failed was a God that did not exist. Instead, the God who took on our suffering and came into the world, who “by viture of his weakness and suffering” came to save us, is the only one who acts in the world–in reality.

Only a suffering God can help.

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Bonhoeffer’s Catechesis: Foundations for his Lutheranism and Religionlessness

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was deeply involved in educating youths. He saw the need for it and was apparently quite skilled, building a reputation in Barcelona for caring for a rambunctious group of students. When teaching at the illegal seminary at Finkenwalde, one of the many subjects he touched upon was catechesis–basic Christian education. Bonhoeffer’s teaching on catechesis revealed that his thoughts on religionless Christianity were already quite embedded at this middle stage of his theology, and that his staunch Lutheranism held throughout his life.

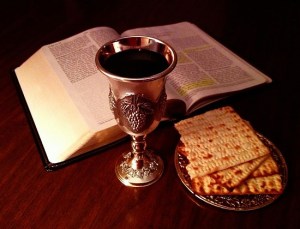

When starting his lectures on catechesis, he began with some commentary on Christian instruction. However, this commentary was fronted with the notion that Christian instruction is embedded in proclamation. Conceptually, this is because those involved in catechesis have been baptized, and, due to their baptism, they are already Christian. Thus, Bonhoeffer declares that, related to the education of young people: “the struggle, the victory belongs to the church because God has long since brought the children into the church through baptism. Whereas the state must first make itself master [Herr], the church proclaims the one who is Lord [Herr].” Bonhoeffer goes on to clarify, “Christian education begins where all other education ceases: What is essential has already happened. You have already been taken care of. You are the baptized church-community claimed by God” (DBWE 14:538).

Because of the status of those learning from the church as the already baptized, Bonhoeffer argues, the church can proclaim from the start the reality that they are already in the church community. Baptism has made this happen, by the power of the Spirit. It would be hard to imagine a more Lutheran understanding of the starting point of Christian instruction than this. For Bonhoeffer, baptism was not an abstraction or a symbol: it was a very real status change of the person being baptized as becoming part of the church-community.

The same lecture series shows Bonhoeffer’s thoughts on religionless Christianity were not merely a late development while in prison. While commenting on “What makes Christian education and instruction possible…” Bonhoeffer notes that it is “baptism and justification” (DBWE 14:539). This obviously hearkens back to the discussion above; baptism as a reality-changing sacrament. But he goes on: “People may well argue about whether religion can be taught. Religion is that which comes from the inside; Christ is that which comes from the outside, can be taught, and must be taught. Christianity is doctrine related to a certain form of existence (speech and life!)” (ibid, 539-540).

Bonhoeffer here links religion with that that comes from within–something he not-infrequently links to idol-building. Religion in his own time is what allowed the German Christian movement to join and overwhelmingly support the Reich Church of the Nazis. By contrast, Christ comes from the outside, through baptism, and can and must be taught. Our religious ways are attitudes we shape and create, but Christ, the God-reality, comes from outside of us and must be proclaimed. And, ironically, this leads to true foundations of doctrine that entail a “certain form of existence” which Bonhoeffer clearly links to the reality of everyday life but also to resistance and calls to repentance for the church itself.

In this way, we can see the foundations, at the least, are here in Bonhoeffer’s thought for religionless Christianity. The fact that there is a contrast between religion and Christ is quite evident. The link between Christ, word, and sacrament is fully there. So while some may claim Bonoheffer’s religionless Christianity is anti-ritual, this cannot be further from the truth. Here, Bonhoeffer very clearly links religionlessness to sacrament and true faith. For Bonhoeffer, what signifies religion is not traditions or sacrament, but rather that which comes from within us and causes us to create our idols.

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“The Foolishness of God” by Siegbert W. Becker- An engaging struggle

Many years ago, when I was deep into apologetics and trying to figure out my place in the world and in my faith, my dad gifted me with a copy of The Foolishness of God: The Place of Reason in the Theology of Martin Luther by Siegbert W. Becker. Well, a lot has changed since then, and I am still trying to figure out my place in the world and in my faith, but I am much more skeptical of apologetics than I was then… to say the least. I re-read The Foolishness of God now, probably more than a decade after my original reading. It was fascinating to see my scrawling notes labeling things as ridiculous or wrong when I now basically think a lot of it is right. On the flip side, I still have quite a bit to critique. I’ll offer some of my thoughts here, from a viewpoint of a progressive Lutheran.

Becker starts by quoting several things Luther says about reason, from naming it “the devil’s bride” to being “God’s greatest and most important gift” to humankind (1). How is it possible that reason can be a great evil, vilest deceiver of humanity while also being one of the most enlightening parts of human existence? One small part of Luther’s–as Becker interprets him–answer is that it depends on what reason is being used for. That’s a simplistic answer, though, suggesting one could categorize things like nature and science (reason is good!) and judging biblical truth (reason is bad!) into neat boxes for Luther. In some ways, this can be done; but in others, when one digs more deeply, it becomes clear that such an application would be an okay rule of thumb for reading Luther but would not be accurate all the way through. For example, where Luther sees the Bible teaching directly on nature or science, using reason to judge that teaching would be rejected. This, of course, opens up my first and probably greatest point of disagreement with Luther’s theses about reason. And yet, it also is confusing, because in some ways I’m not sure I wholly disagree.

What I mean by this is that I, too, am skeptical of the use of human reason for any number of… reasons. This is especially true when it comes to thinking about God. Supposing it is true that there is a God and that God is an infinite being in any way–whether it is infinitely good, infinitely powerful, etc. In that case, it seems that to suggest that we can use reason to grasp things about God is a fool’s errand. We are not infinite and can certainly not grasp the infinite; how can we expect our brains that cannot contain the multitudes to reason around God? On the other hand, in many ways reason is all we have. Even supposing God exists, we ultimately act or believe in ways and things we think are reasonable. And I’m deeply skeptical of a denial of this. What I mean by the latter is that I simply do not believe that people can believe things they think are inherently anti- or irrational. Becker outright makes the claim that Luther–and presumably Becker himself–do believe such things. Time and again, Becker flatly states that some claims of Christianity are inherently contradictory–be it the Trinity, the Incarnation, or [for Lutherans] Christ’s presence in the Lord’s Supper. So Becker is claiming that Luther truly did believe in things he thought were inherently anti-reason and irrational. But when push comes to shove, I strongly suspect that Luther and people like him who make these claims think that it imminently reasonable to believe in the irrational. Even while claiming that they believe in things they claim they think are contradictory, they are doing so because it makes sense to them. And this is precisely because of the limitations of human reason and thinking. We cannot go beyond our own head, we have to go with what we think is right, perhaps even while claiming we think it is irrational to do so.

Setting aside that question, Luther’s solution to the gap between the finite and the infinite is that of revelation. Because God became incarnate and came to humanity, we, too, can know God. God revealed God to us. Becker rushes to use this to attempt to counter what he calls Neo-orthodox interpretations that stack the Bible against Christ. He writes, “Neo-orthodoxy’s distinction between faith in Christ and faith in statements, or ‘faith in a book,’ is artificial and contrary to reason. By rejecting ‘propositional revelation’ and making the Bible only a ‘record of’ and ‘witness to’ revelation, the neo-orthodox theologians drain faith of its intellectual content” (11). I find this deeply ironic wording in a book that later has Becker outright claiming that Luther–and by extension Becker himself–believed things that are contrary to reason and affirming that this is a perfectly correct (we dare not say “reasonable”) thing to do. In my opinion, at least, it is quite right to make the distinction between faith in Christ and faith in statements. That doesn’t mean the Bible is devoid of revelation or can have no revelation; rather, it means that, as Luther put it [paraphrasing here], the Bible is the cradle of Christ. But to put the Bible then on par with Christ as a similarly perfect revelation is to make a massive mistake, as people, including Lutherans like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, have argued.

All of this might make it seem I have a largely negative outlook on Becker’s work. Far from it. I found it quite stimulating and generally convincing on a number of points. Most of it, of course, is exegesis of Luther’s own views of reason. And I think that Luther, while he could stand to be far more systematic and clear, makes quite a few excellent points about reason. When it comes to trying to draw near to God, reason does not do well. Why? Our own era has so many arguments in philosophy of religion about the existence of God. Anyone who has read or engaged with the minutiae of analytic theology or analytic philosophy getting applied to God has experienced what I think, in part, Luther was warning against. Philosophers, apologists, and theologians continue to attempt to plumb the very nature of God and gird it up with scaffolds of reason, providing any number of supposed arguments for God’s existence, proofs of Christological points, and the like. Bonhoeffer, a favorite theologian of mine, put many of these attempts to shame in a succinct quote: “A God who could be proved by us would be an idol.”

I think a similar sentiment applies to so much about God and even just the universe. I mean, we’re on a planet that is less than a speck in a cosmos that is so unimaginably huge and ancient that thinking we can comprehend it is honestly shocking. Sure, we can slap numbers on it, using our human reason to try to slice the universe into chewable bites, but when we find out things like how it takes more than 1 million Earth’s to fill the Sun, and that our Sun isn’t even remotely the largest star, nor the largest solar system, etc… how absurd is it to think we really comprehend any of it? And so, for me, from a very different angle, Luther’s words about reason make sense. Sure, we can use it to try to understand little slices of nature. But when we start to line it up with things of the infinite, it may be better to just let God be God.

The Foolishness of God is a fascinating, engaging, and sometimes frustrating work. In a lot of ways, it’s like engaging with Luther’s own works. It’s not systematic; it doesn’t cohere; it’s intentionally provocative. I will likely give it another read one day, and who knows where I–and it–shall stand?

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Martin Luther and the Rule of Faith” by Todd R. Hains

Martin Luther and the Rule of Faith by Todd R. Hains explores Martin Luther’s reading of scripture. It’s a topic that has occupied theologians for hundreds of years, but Hains presents it in a way that allows readers to see Luther’s reading of scripture contextually.

Hains notes Luther’s words against reason and notes how it has been misunderstood. Then, he turns to the questions that arose in reading scripture, including the question of when scripture might be read against itself. This led Luther, Hains argues, to reading scripture in much the same way as others in church history had–reading it as a book of faith that speaks with the power of the Spirit (11).

The rule of faith, however, is to be understood not abstractly but as reading through ancient catechesis- the use of the Ten Commandments, the Apostle’s Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer. By understanding this as the foundation of Luther’s reading of scripture, the notion of sola scriptura as well as his reading in certain places becomes more evident. Not only does Luther follow the ancient catechesis in his own catechism (57ff), but it also helps illuminate how Luther read the Law (89ff especially). Here, Hains notes, that Luther argued that the Torah would be seen by reason as a “jumble of stories and random laws” while the rule of faith leads to seeing the Torah as books that “teach faith and its fruits” (93).

Martin Luther and the Rule of Faith is an intriguing look at Luther’s reading of scripture. Readers interested in what Luther may have meant by sola scriptura and how he practiced it will find it insightful.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“Bonhoeffer’s America: A Land Without Reformation” by Joel Looper

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s time in America has been the subject of much scholarly discussion. It is clear it had enormous impact on his theology, but what hasn’t been as clear is exactly what kind of impact it may have had. Joel Looper’s phenomenal, challenging work, Bonhoeffer’s America: A Land Without Reformation not only seeks to answer definitively what kind of impact Bonhoeffer’s time in the United States had on the man and his theology, but also shows how extremely timely Bonhoeffer’s words and warnings about American theology can be for us today.

The book is divided into three parts. The first, “What Bonhoeffer Saw in America,” is Looper’s deep narration of Bonhoeffer’s life in America. Here, Looper delves deeply into Bonhoeffer’s coursework at Union Theological Seminary, who he interacted with, and what he himself reports about the situation with American theology. This part lays the foundation for the rest of the book. Here, Looper’s depth of knowledge and exploration of Bonhoeffer’s theology is on full display. It’s not just a report of Bonhoeffer’s time and words, but also an analysis that helps elucidate themes in Bonhoeffer’s writing from this time period that make much more clear what his issues were with American theology. Much of Bonhoeffer’s writing from his time in America is difficult to understand or comprehend without significant knowledge of contemporary issues, and Looper does an admirable job filling in those gaps, showing readers the background for understanding many of Bonhoeffer’s critiques. For example, some have utilized Bonhoeffer’s hard critiques of the social gospel to attempt to decry modern movements for social justice. However, Looper demonstrates that Bonhoeffer’s critique of the social gospel is not because it seeks to bring justice, but rather because it displaces the very gospel itself–that is, it doesn’t center revelation in Christ in the Christian message (see, for example pages 41, 46, and especially 48-49). The problem is not the ultimate efforts to feed the poor, stand with the oppressed, &c. The problem is, rather, the starting point of theology and its abandonment of revelation as the ultimate grounds.

The second part of the book focuses on Bonhoeffer’s analysis of American Protestantism specifically. American theology, as read by Bonhoeffer, had a primary problem in that it was “Protestantism without Reformation.” The meaning of this phrase is complex, but Looper notes that for Bonhoeffer, it can be traced back to Wycliffe and the Lollards. This sounds like an obscure point, but Looper, making Bonhoeffer’s own arguments clearer, shows how and why one might take this to be the case, particularly in the circles in which Bonhoeffer ran. It is clear, of course, that Bonhoeffer was not exposed to all of American theology, but what he saw ran in this vein, and the more conservative branches of theology he encountered were, in his opinion, little more than the most blunt and un-nuanced attempts to enforce orthodoxy. The Protestantism of the United States is so influenced by the strands Bonhoeffer mentioned that even Jonathan Edwards, cited by many as one of the greatest theologians America as produced, doesn’t even mention the church in his discussion of what one needs to be saved (75-76). American churches gave up any kind of confessional standard, only enforcing them after splitting again and again, and, in doing so, abandoned the Christian confession (86). American Protestants, for Bonhoeffer, no longer had something against which to protest, because they had severed themselves so distantly from the one true, holy, catholic church (86-87).

Even more damning is Bonhoeffer’s analysis of secularization in America. The pluralism enforced in America led to a kind of secularization of the church and idolization of the individual to the point that the allegiance was given to the nation state rather than to the church and God (102-103). This can be traced, again, to English dissenters who formed the backbone of colonial America. The secularization of the church is not due to some outside force acting upon it, but rather due to the church itself abandoning the word and being, again, a Protestantism without any kind of Reformation. In America, rather than having state churches, secularization came into play precisely because of the focus on freedom and independence–the church then becomes a mouthpiece for the alleged freedom the state provides (106-107).

Bonhoeffer’s own oft-misunderstood theology of the two kingdoms is, according to Looper, central to his understanding of the Gospel as well. Here is where Bonhoeffer’s Lutheranism is so central to his understanding of the problems with American theology and beyond. The call for “thy kingdom come” must include both church and state precisely because of the two kingdoms theology–the church and state are both necessary and linked to one another (113-114). Thus, the famous phrase from Bonhoeffer about “seizing the wheel” is not actually revolutionary but rather counter-revolutionary. Bonhoeffer saw the Nazis as the revolutionaries, and such an understanding fits well within the Two Kingdoms theology Bonhoeffer so ardently supported.

The third part of the book centers around objections to both Bonhoeffer’s view of the American church and objections that seek to counter this narrative. For example, much has been made of Bonhoeffer’s largely positive analysis of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. Looper doesn’t downplay this positive theme in Bonhoeffer’s analysis of America, but he does contextualize it. The Abyssinian Baptist Church was, to our knowledge, the only African American church he encountered in the United States apart from perhaps one or two Sundays in the American south (131). Bonhoeffer has threads that sound like W.E.B. Du Bois in some of his analysis of the American situation, such as when he talks about what is “hidden behind the veil of words in the American constitution saying ‘all men are created free and equal'” (136). It’s clear this had a positive and even eye-opening impact on Bonhoeffer, and traces of this can be found in his theology. Bonhoeffer’s own discussion of Jews in Germany, such as in his “The Church and the Jewish Question” may have been somewhat influenced here. Looper analyzes Bonhoeffer’s discussion of the Jewish people and shows how, while at times it is couched in problematic language, it demonstrates a deeper understanding and concern than one could credit him merely given his background or upbringing. (The whole section on this is a fascinating read, showing clear analysis that’s well-worth reading. See p. 141-146 in particular.) Bonhoeffer’s theology, however, remained firmly German Lutheran, and his own life-risking efforts in behalf of the Jews were not traceable to some kind of vague Western morality of “equality of all” but rather, Looper asserts, clearly based upon his Christology (150). Thus, Bonhoeffer’s experience with the Abyssinian church demonstrates a caveat in his analysis of American theology. Rather than a total rejection of all American theology, Bonhoeffer’s words ought to be seen directed exactly as they were, against the overwhelmingly popular academic streams of thought in contemporary American theology.

Bonhoeffer’s imprisonment and his now famous Letters and Papers from Prison have led some to argue that he changed his views profoundly while in prison. Looper instead notes that his late-stage theology has continuity with that of his earlier life.

Looper’s work serves as a powerful challenge to many theologies of today. For those adhering to modern forms of the social gospel, Bonhoeffer’s warnings and critiques of that movement from his own time continue to apply: are these movements removing Christ from the center? For progressive Christians, Bonhoeffer’s critique of the social gospel can loom large–“Do such [progressive] theologies tend to respond to the critique of the word [revelation, Scripture] and think critically about their subjects in its wake? Or, rather, do they often begin with the (oppressed) self and work from the experience of that self and the non-ecclesial community with which it identifies? If the latter, are these theologies then only variants of ‘religious’ logic…?” (197-198). For conservatives, especially American evangelicals, Looper notes that the constant efforts to try to maintain a “seat at the table” in the larger world and their defense of their institutions, even to the point of, as many have said, voting while “holding their nose” for someone who, ethically, cannot be defended, would have been seen by Bonhoeffer as “Niebuhrian realism, pragmatism par excellence, and, in working from this script, evangelicals both brought the name of Christ into disrepute and forgot how the economy of God and of the church are supposed to work… Bonhoeffer would have called this evangelical struggle a cause of American secularization, not a buffer against it” (196). Bonhoeffer would see American theology today as a total abandonment of Protestant norms, exactly because of his theology of two kingdoms (joined with Luther’s) and because of the stark pragmatism of the right and the rush to de-center the Gospel on the left (198). Looper’s book thus serves as a blunt reminder of the dangers of our modern theological era and the need to offer correctives.

I have now read more than 70 books by or about Dietrich Bonhoeffer, his theology, and the world he inhabited in order to try to understand more about the man and his theology. Bonhoeffer’s America: A Land Without Reformation easily ranks in the top 10 of those books. Anyone who is interested in learning more about Bonhoeffer’s theology should consider it a must read. More importantly, though, those wishing to have an understanding of American theology and its problems to this day should seek out this fantastic book. I highly recommend it without reservation.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Bonhoeffer: God’s Conspirator in a State of Exception” by Petra Brown

It’s no secret that I have been deeply impacted by Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology. However, as with everything, I believe it is important to read views which are critical of your own. Sometimes, this can help moderate your own enthusiasim for a view by showing potentially problematic aspects of it. Other times, reading something which disagrees with your views can help confirm you in that view as you rebut the critique. Petra Brown’s book, Bonhoeffer: God’s Conspirator in a State of Exception is a remarkable critique leveled directly at Bonhoeffer’s ethic. I found it enlightening and, at times, course-correcting.

The central point Brown argues that Bonhoeffer’s ethic is dangerous because it essentially allows the individual Christian disciple to justify essentially any form of violence so long as they believe they are living in a state of “exception.” Brown cites numerous examples of Christians who used violence, claiming Bonhoeffer for support when challenged on it.

The state of exception is developed by Brown through the lens of Carl Schmitt, a Nazi jurist who developed the notion of “state of exception” as “a state of emergency which requires decisive action by the sovereign (in Schmitt’s case) or by other actors within the state” (5). Schmitt is explicitly cited by Brown as the lens through which she’s viewing the state of exception and analysis of Bonhoeffer, though she also clearly state’s Bonhoeffer’s own concept of exception is intended “in a fairly straightforward way, based on Machiavelli’s concept of necessita” (106). Brown rigorously documents Bonhoeffer’s writings showing that he did speak about a state of exception, along with the need for potential individual action on the part of the disciple. However, Brown’s own definition of exception is, by her own argument, placed squarely within Schmitt’s writings, not those of Bonhoeffer. And, since Brown denotes a significant divergence between the two, this seemingly undercuts her central point. Indeed, at times this reader wondered if the point was more akin to arguing that Bonhoeffer’s ethic could be misunderstood in light of other writers on states of exception, thus becoming dangerous because of that misunderstanding. Yet Brown herself seems to be arguing that Bonhoeffer’s ethic is problematic in just this sense: that it can and does yield individual, “lone wolf” type violence. The tension between these two points is, to my eye, not resolved.

Brown does make attempts to unite Bonhoeffer’s state of exception with that of Schmitt’s, but these arguments are tenuous. For example, she notes that one possible objection to her use of Schmitt with Bonhoeffer is that comparing Schmitt’s ideas with the “emerging ideas of Bonhoeffer” is mistaken because Schmitt was “a German Catholic who explicitly claimed to speak from a Catholic position” (112). Brown argues instead that Schmitt’s position was “highly idiosyncratic” compared to traditional Catholic political stance such that it was “neither neoscholastic, nor Romantic as German Catholicism tended to be at the time” (ibid). Of course, showing Schmitt had theological distance from Roman Catholicism of his time and place does not somehow mean that Bonhoeffer’s state of exception can be seamlessly united with Schmitt. Indeed, it is telling that after making these distinctions, Brown simply moves on with the analysis of Schmitt’s concept of exception rather than attempting to unite it with Bonhoeffer’s. Indeed, she noted earlier that Bonhoeffer’s position is more akin to Machiavelli, from whom she says Schmitt is “a significant departure” (114). This, again, makes it seem as though Brown’s point is less that Bonhoeffer’s ethic itself is dangerous than that it can be dangerous once one unites it with other ethical theories or concepts that are, yes, adjacent to it, but not actually part of it.

On this latter point, I think Brown and I are in general agreement. In fact, Brown’s argument here seems to demonstrate that American evangelicals who cite Bonhoeffer in support of violent acts are doing so by misunderstanding him. But Brown, as far as I saw (and I could have missed something in my own reading), never actually makes this point explicitly. Instead, the implication is that Bonhoeffer’s own ideas are dangerous in that exact way; but that point is not sufficiently established.

Another area in which Brown’s argument loses ground is that she attempts–and fails–to adequately account for Bonhoeffer’s moderation of that state of exception and ethic when related to the church. She acknowledges that Bonhoeffer’s writings about church-community present a significant problem to her reading of Bonhoeffer’s ethic as dangerous (184). However, even as she agrees that one cannot isolate Bonhoeffer’s discussion of ethics from his discussion of the church-community, she works to move Bonhoeffer’s concept of church to that of an individual.

Brown writes, “Bonhoeffer regards the church-community not as an institution, but as a collective person; the personhood of the church-community reflects its identity as the ‘body of Christ’ that is made [up of] ‘actual, living human beings who follow Christ” (187). Thus, she says, “The church community is understood by Bonhoeffer to have ‘personhood,’ and as such I suggest that it can suffer the same isolation experienced by Abraham or the isolated disciple in her obedience to Christ’s call” (ibid). The passage she quotes in support of giving the church-community personhood is from Discipleship (aka The Cost of Discipleship). Brown moves from this quote using the words “actual living beings who follow Christ” to saying the church-community has personhood. However, Bonhoeffer himself, in that very passage which Brown quotes, is not making that point. Instead, Bonhoeffer’s point is made explicitly: the church-community is the physical embodiment of Christ on Earth, preaching God’s word to the world (DBWE 4: 225-226). Thus, for Bonhoeffer, the church-community does not become personal by means of its composition of persons. No, for Bonhoeffer, the church-community has personhood because it becomes Christ to others. And this remarkable claim obviates the difficulty Brown is trying to press. For the church-community is not reducible to a person except that that person is Christ in the world. Therefore, Brown’s argument here fails, because she reduces the church-community to the person in the wrong direction. For her argument to work, it must be reducible, again, to the Christian acting as lone wolf, possibly through violence. But in fact, Bonhoeffer’s reduction is to bring it all to Christ.

One difficulty for Brown is that shared by her imagined–and real–opponents in interpreting Bonhoeffer. Namely, by lifting his name and ethic of the pages of a book and the specific time in which he lived and plugging it in to modern debates, they’ve assumed the context and intent of his ethic today. I need to unpack this a bit. It is abundantly clear that Bonhoeffer’s ethic is not meant to be a list of principles from which people are supposed to draw to make their decisions. Indeed, his ethic does encourage individual action. However, it always does so within the community of believers. Brown’s rebuttal for this was mentioned above, but I think it is worth noting again that community for Bonhoeffer is irreducible to the individual except that of Christ. Thus, the lone wolf violence about which Brown worries and which several have attempted to justify using Bonhoeffer’s words is deeply mistaken in putting Bonhoeffer’s name to it. Just as Bonhoeffer argues one cannot have church without sacrament, so too does he insist upon the church community as working together to embody Christ on Earth. Acting in state of exception does not mean merely acting individually–it means acting along with Christ and the church.

Brown’s arguments do have merit. It is demonstrable that many violent acts have been done in the name of, or at least justified after the fact by, Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Brown’s argument that Bonhoeffer’s own ethic justifies this violence is, I believe, mistaken. However, her argument has powerful force if one includes those positions which are adjacent to Bonoheffer’s. So, for example, if one integrates others’ views of a state of exception, it becomes much simpler to justify violence. If one ignores or is ignorant of Bonhoeffer’s insistence upon the church-community and acting ethically alongside that, it becomes much easier to justify violence. So, is Bonhoeffer God’s conspirator, ushering in the possibility for violent acts by Christians? Yes and no. Yes, if Bonhoeffer’s ethic is read divorced from much of its context and with others’ interpretations and concepts smuggled in. No, if one takes Bonhoeffer at his own words.

There is, however, one clear exception to this. Brown presses hard on a sermon Bonhoeffer gave in Barcelona in which he clearly stated that even violent acts could be sanctified. She states, “I don’t believe that the 1929 Barcelona lecture can be dismissed as an aberration” for Bonhoeffer’s ethic. Her attempt to unify this lecture with Bonhoeffer’s Ethics and Discipleship is intriguing. I also think that we ought to see Bonhoeffer’s ethic more as unified whole than as a collection of different positions. The Barcelona lecture needs to fit into that somewhere. Of course, Bonhoeffer himself wrote of having some regrets about what he’d written before, so one wonders if it’s possible that, due to the influence of pacifism on his views, he would have wholly rejected what he said in Barcelona. That, or, as others have argued, perhaps Bonhoeffer was moving along a continuum of a Lutheran view of ethics, and one can unify the whole through that. Whatever the case, more work needs to be developed to discover what was meant by Bonhoeffer in Barcelona, or whether Brown’s case succeeds at this point.

Petra Brown’s Bonhoeffer: God’s Conspirator in a State of Exception presents a significant challenge for Bonhoeffer scholarship. Those who wish to engage with Bonhoeffer’s ethics–particularly those of resistance–ought to engage carefully with Brown’s critique.

All Links to Amazon are Affiliates links

Links

Dietrich Bonhoeffer– read all my posts related to Bonhoeffer and his theology.

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Bonhoeffer’s Reception of Luther” by Michael P. DeJonge

Michael P. DeJonge’s thesis in Bonhoeffer’s Reception of Luther may be summed up as saying the best interpretative framework for understanding Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology and thought is by understanding him as a Lutheran theologian specifically engaged in Luther’s thought.

Michael P. DeJonge’s thesis in Bonhoeffer’s Reception of Luther may be summed up as saying the best interpretative framework for understanding Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology and thought is by understanding him as a Lutheran theologian specifically engaged in Luther’s thought.

DeJonge supports his thesis primarily through two strands of evidence: first, by showing Bonhoeffer’s close readings of and interactions with Luther; and second, by demonstrating that Bonhoeffer’s perspective on important controversies was a Lutheran perspective.

Bonhoeffer’s interactions with Luther outpace his interactions with any other theologian. DeJonge cites a statistic: Bonhoeffer cites or quotes Luther 870 times, “almost always approvingly”; “The next most frequently cited theologian is a distant second, Karl Barth with fewer than three hundred” (1). This alone may serve to demonstrate Bonhoeffer’s concern for interacting with Luther, but DeJonge goes on to note that Bonhoeffer also strove to correct competing interpretations of Luther, and affirm specifically Lutheran doctrine. For instance, in his interactions with Karl Holl, one of his teachers, he goes against Holl’s interpretation of Luther’s view of religion, arguing that Luther’s Christology saves one from idolatry of the conscience, which he felt Holl may have slipped into. Bonhoeffer also affirmed the emphasis on Christ’s “is” statements when it came to the Lord’s Supper, defending the position that “this is my body” means Christ is truly present in the Supper (70ff).

DeJonge’s argument expands to a demonstration that Bonhoeffer aligned with a Lutheran understanding on important issues. The Lord’s Supper has already been noted, but it is worth pointing out that in regards to this, Bonhoeffer explicitly sided with Luther against Karl Barth and the Reformed tradition, which argued that the finite could not contain the infinite. Instead, Bonhoeffer affirmed that, by virtue of the infinite, the infinite could be contained in the finite; allowing for a Lutheran understanding of real presence in the Supper. Another major controversy DeJonge notes is that of the interpretation of Luther’s “Two Kingdoms.” DeJonge argues that Bonhoeffer has been misunderstood as rejecting Luther’s doctrine in part because Luther’s doctrine itself is misunderstood. Thus, DeJonge engages in a lengthy section in which he traces the influence of Troelsch on the understanding of Luther’s Two Kingdoms and how often it is Troelsch’s understanding rather than Luther’s that is seen as “the” doctrine of the Two Kingdoms. Going against this, Bonhoeffer’s thoughts on the Two Kingdoms are closer to Luther’s position than many have argued.

DeJonge also interacts with other interpretations of Bonhoeffer, such as an understanding of Bonhoeffer as a pacifist, which has been a common understanding among some. Utilizing his deep analysis of the Two Kingdoms doctrine, DeJonge counters that Bonhoeffer’s comments about resisting the Nazis align with this doctrine much more closely than they do to a pacifist understanding. Like Stephen R. Haynes’s The Battle for Bonhoeffer, DeJonge notes that Bonhoeffer’s resistance cannot be linked explicitly to the Nazi treatment of the Jews. Though it is clear that Bonhoeffer detested this treatment, DeJonge argues he did so not through a broadly humanitarian theology (going against some interpreters here), but rather due to his understanding, again, of the Two Kingdoms. When the Nazis sought to attack the Jews, particularly by separating them from the so-called German Christians, they issued a direct assault on the body of Christ–the church. Thus, Bonhoeffer’s resistance to these ideals, again, springs from a Lutheran understanding of the Two Kingdoms. (As an aside, it is worth nothing DeJonge also acknowledges the contributions some aspects of Martin Luther’s own writings had to the Nazi ideology. However, DeJonge here shows how Bonhoeffer’s understanding of his theology set him against these anti-Semitic notions.)

Finally, DeJonge demonstrates that Bonhoeffer’s view of justification–certainly a vastly important doctrine for Luther and Lutherans–ought to be properly understood as Lutheran rather than anything else. Time and again, throughout the book, DeJonge carefully demonstrates how an interpretation of Bonhoeffer suffers when not understood in a Lutheran lens. Over and over, readings of Bonhoeffer that make sense in one context are shown to fail when compared to the whole of his writings. DeJonge also manages to offer a coherent account of Bonhoeffer’s theology that does not set an “early Bonhoeffer” against a “late Bonhoeffer” nor does it read the whole of his thought through any one work. As such, DeJonge offers a truly compelling reading of the totality of Bonhoeffer’s work.

Bonhoeffer’s Reception of Luther is an incredibly important work for understanding the theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Anyone who is interested at all in the theology of Bonhoeffer and understanding it fully would do well to read and digest it. I cannot recommend it highly enough for those who wish to understand the theology of this man.

Disclaimer: I was provided with a copy of the book for review by the publisher. I was not required to give any specific kind of feedback whatsoever.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Theologian of Reality” by André Dumas

André Dumas’ Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Theologian of Reality is a deep look at the theology and philosophy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, offering the thesis that Bonhoeffer’s primary aim was to show that God is reality and really interacts with the world. Though this may seem a rather mundane claim, Dumas’s point is that “reality” is rather strictly defined for Bonhoeffer, and, as he argues, this leads to some intriguing insights into Christian theology and philosophy.

André Dumas’ Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Theologian of Reality is a deep look at the theology and philosophy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, offering the thesis that Bonhoeffer’s primary aim was to show that God is reality and really interacts with the world. Though this may seem a rather mundane claim, Dumas’s point is that “reality” is rather strictly defined for Bonhoeffer, and, as he argues, this leads to some intriguing insights into Christian theology and philosophy.

One side note before reviewing the work: this book was originally published in French in 1968 and in English in 1971. Dumas is, in part, responding to the “death of God” movement that turned Bonhoeffer into a kind of secular saint Nevertheless, this work is highly relevant to today’s theological and philosophical inquiry as well, particularly due to the keen interest in Bonhoeffer’s life and work.

Central to Bonhoeffer’s thought, argues Dumas, is the struggle between objective revelation and existential interpretation. Alongside this is the question of reality, which, for Bonhoeffer, was this-worldly. Christianity is not to be reduced to a religion, in this case meant to denote a faith that points to the other-world or beyond this world to a different and disconnected reality. Instead, it is about this world, the very one we are in. Dumas notes that “Bonhoeffer was… drawn to the Old Testament, because the living God within it becomes known only in the here-and-now of human life. The absence in the Bible of any speculation about the beyond, about the abode of the dead, about inner feelings, or about the world of the soul, strongly differentiates the faith and anthropology of Israel from the various religions that surround it. For Israel [and Bonhoeffer], God can only be encountered in the reality of this world. To withdraw from it is to find oneself beyond his reach” (144). Alongside this is the need to avoid either total subjectivism about the word of God while also not falling into the danger of objectification.

In order to combat these difficulties, Dumas argues that Bonhoeffer sees Christ as the structure of the world, God entering reality to structure it around himself. Thus, for Bonhoeffer, Christ is “the one who structures the world by representing its true reality before God until the end” (32). This is important, because this means that Bonhoeffer is not encouraging a Christianity that sees the ultimate goal as “salvation” from the world. “When biblical words like ‘redemption’ and ‘salvation’… are used today, they imply that God saves us by extricating us from reality, blissfully removing us from any contact with it. This is both gnostic and anti-biblical” (ibid). Christ is the true center of all things, and the structure which upholds the true reality, one with Christ at the center.

These central aspects of Bonhoeffer’s thought are then the main force of Dumas’s arguments when it comes to “religionless Christianity” and the questions of realism and idealism. Regarding the latter, Nietzsche remains a major force in philosophy as one who also argued for a kind of realism. But Nietzsche and Bonhoeffer, though having similar influences, came to utterly different conclusions and interpretations of that “realism.” Nietzsche “cannot get beyond the terrible ambiguity of loneliness in the world, against which Bonhoeffer rightly affirms the reality of co-humanity, willed by God in his structuring of the world, and embodied by Christ in his life and death for others” (161). Thus, “Bonhoeffer… agrees with Nietzsche on the primacy of reality… But Bonhoeffer disagrees with Nietzsche about the nature of that reality” (ibid). And Bonhoeffer’s vision of reality is concrete as well, but one which avoids the stunning loneliness and hopelessness of Nietzsche.

The non-religious church is a major question in Bonhoeffer’s later thought, but one which must be viewed holistically with the rest of Bonhoeffer’s ideas, as Dumas argues. Thus, the non-religious church is not an atheistic one or a “secular Christian” one. Instead, it is one which “will then rediscover a langauge in speaking of God [that] will not release one from the earth… The resurrection will not re-establish the distance between God and man that was overcome by the cross… Instead, [the community of the church] will be nourished by its participation here on earth in the task of restructuring everyday life, just as Jesus Christ did earlier on its behalf” (209). This cannot be interpreted as a call to go against faith in Christ but rather as a radical call to make Christ the center once again. This is the linchpin of Bonhoeffer’s Ethics as well, for it calls to make Christ the center, a re-structuring and ordering of the world which will change everything, and an order which Bonhoeffer died following.

Dumas is an able interpreter of Bonhoeffer, and one who avoids entirely the danger of separating Bonhoeffer’s work into distinct eras or prioritizing some works over others. Dumas argues instead that Bonhoeffer’s thought is unified, though of course it does develop over time. Therefore, Dumas finds Sanctorum Communio just as important as Letters and Papers from Prison for understanding Bonhoeffer’s thought. His book demonstrates the ability of Bonhoeffer not simply as theologian or martyr but also as philosopher, drawing from Hegel and others to create a systematic view of the world with Christ as the center, as the structure of reality. Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Theologian of Reality is a fascinating work that ought to be read by any looking to understand the works of Bonhoeffer.

Disclaimer: I was provided with a copy of the book for review by the publisher. I was not required to give any specific kind of feedback whatsoever.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Book Reviews– There are plenty more book reviews to read! Read like crazy! (Scroll down for more, and click at bottom for even more!)

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from quotations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited; images are often freely available to the public and J.W. Wartick makes no claims of owning rights to the images unless he makes that explicit) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Perspicuity of Scripture in the Lutheran Reformers: Reformation 500

2017 marks the 500th anniversary of what is hailed by many as the start of the Reformation: Luther’s sharing his 95 Theses. I’ve decided to celebrate my Lutheran Protestant Tradition by highlighting some of the major issues that Luther and the Lutherans raised through the Reformation period. I hope you will join me as we remember the great theological (re)discoveries that were made during this period.

2017 marks the 500th anniversary of what is hailed by many as the start of the Reformation: Luther’s sharing his 95 Theses. I’ve decided to celebrate my Lutheran Protestant Tradition by highlighting some of the major issues that Luther and the Lutherans raised through the Reformation period. I hope you will join me as we remember the great theological (re)discoveries that were made during this period.

Perspicuity of Scripture in the Lutheran Reformers

Luther himself wrote on perspicuity in no uncertain terms:

[T]hat in Scripture there are some things abstruse, and everything is not plain–this is an idea put about by the ungodly Sophists… I admit… that there are many texts in the Scriptures that are obscure and abstruse, not because of the majesty of their subject matter, but because of our ignorance of their vocabulary and grammar; but these texts in no way hinder a knowledge of al the subject matter of Scripture. (Luther, The Bondage of the Will, 110, cited below)

So far as I know, Luther did not change his stance on the perspicuity of Scripture. As the Reformation continued, however, it became clear that such a stance might not be appropriate regarding the entirety of every declaration of Scripture. Lutheran reformers qualified perspicuity, noting that it applied only to that which pertains to salvation.[1] Heinrich Schmid, in his Doctrinal Theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church (translated 1875) compiles quotations from the major early Lutheran reformers to outline what Lutherans taught. Regarding perspicuity, Schmid notes:

If the Sacred Scriptures contain everything necessary to salvation, and if they alone contain it, they must necessarily exhibit it so clearly and plainly that it is accessible to the comprehension of every one; hence the attribute of Perspicuity is ascribed to the Sacred Scriptures… But whilst such perspicuity is ascribed to the Sacred Scriptures, it is not meant that every particular that is contianed in them is equally clear and plain to all, but only that all that is necessary to be known in order to salvation is clearly and plainly taught in them… it is also not maintained that the Sacred Scriptures can be understood without the possession of certain prerequisites [such as the language, maturity of judgment, unprejudiced mind, etc.].(Schmid, 87-88, emphasis his)

Schmid’s summary of Lutheran doctrine in the Reformation period sounds different from what Luther taught in The Bondage of the Will, but he shows from direct citations that this is the direction Lutherans moved in regarding perspicuity. To whit, Gerhard:

It is to be observed that when we call the Scriptures perspicuous, we do not mean that every particular expression, anywhere contained in Scripture, is so constituted that at the first glance it must be plainly and fully understood by every one. On the other hand, we confess that certain things are obscurely expressed in Scripture and difficult to be understood… (quoted in Schmid, 89)

Quenstedt:

We do not maintain that all Scripture, in every particular, is clear and perspicuous. For we grant that certain things are met with in the sacred books that are very obscure… not only in respect to the sublimity of their subject-matter, but also as to the utterance of the Holy Spirit… (ibid, 90, Quenstedt goes on to deny that there are doctrines that are so obscure that they “can nowhere be found clearly and explicitly”)

Hollaz:

The perspicuity of Scripture is not absolute, but dependent upon the use of means, inasmuch as, in endeavoring to understand it, the divinely instituted method must be accurately observed… (ibid, 91)

The whole section clarifies and explains the earliest Lutheran teaching regarding perspicuity of Scriptures, and it is clear that it is acknowledged that not every single text is plain, that the guidance of the Holy Spirit, among other things, is required to understand Scripture rightly, and that plain passage of Scripture are to be used to interpret those which seem obscure.

As I’ve argued elsewhere, this shift in perspective on perspicuity happened due to the very real differences on some major doctrines within the Protestant movement itself. If every single statement the Scriptures made about doctrine were so clear, how could such divisions exist within a movement that was upholding sola scriptura? The answer was that perspicuity applied to that which is essential for salvation, and that shift in perspective can be observed in the writings of the Lutherans listed here.

What applications might this have? The first is that the many attempts by Christians to argue for their own doctrinal perspectives simply by appealing to the perspicuity of Scriptures fails. To argue that someone else denies perspicuity of Scripture because they disagree on certain doctrinal positions is an abuse of the doctrine of perspicuity of Scriptures. It also shows an incapacity to show one’s own point clearly from the Scriptures themselves. A second application is that it acknowledges some of the difficulty in understanding Scripture rightly.

The doctrine of perspicuity is a major aspect of Reformation theology. It should not, however, be over-generalized and abused in the way that it has, unfortunately, often been used.

[1] In researching this post, I noticed that the Wikipedia page on the clarity of Scripture has been edited to suggest without qualification that all Lutherans hold to the notion that “Lutherans hold that the Bible presents all doctrines and commands of the Christian faith clearly. God’s Word is freely accessible to every reader or hearer of ordinary intelligence, without requiring any special education.” The citations provided to show that all Lutherans hold to this teaching are not to any of the early Lutheran reformers, nor are they citations of the Book of Concord; rather, they are references to two sources published by a publishing house of one form of American Lutherans. These sources are from 1934 and 1910, respectively, and not in the Reformation period nor do they, so far as I can tell, speak for all Lutherans. Given the evidence cited above from Quenstedt, Gerhard, and the like, I find it hard to believe such a claim could be substantiated.

Sources

Martin Luther, The Bondage of the Will in Luther and Erasmus: Free Will and Salvation edited by Rupp and Watson (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1969).

Heinrich Schmid, The Doctrinal Theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Please check out my other posts on the Reformation:

I discuss the origins of the European Reformations and how many of its debates carry on into our own day.

The notion of “sola scriptura” is of central importance to understanding the Reformation, but it is also hotly debated to day and can be traced to many theological controversies of our time. Who interprets Scripture?

The Church Universal: Reformation Review– What makes a church part of the Church Universal? What makes a church part of the true church? I write on these topics (and more!) and their origins in the Reformation.

The Continuing Influence of the Reformation: Our lives, our thoughts, our theology– I note the influence that the Reformation period continues to have on many aspects of our lives.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Indulgences are Worse than Useless: Reformation 500

2017 marks the 500th anniversary of what is hailed by many as the start of the Reformation: Luther’s sharing his 95 Theses. I’ve decided to celebrate my Lutheran Protestant Tradition by highlighting some of the major issues that Luther and the Lutherans raised through the Reformation period. I hope you will join me as we remember the great theological (re)discoveries that were made during this period.

2017 marks the 500th anniversary of what is hailed by many as the start of the Reformation: Luther’s sharing his 95 Theses. I’ve decided to celebrate my Lutheran Protestant Tradition by highlighting some of the major issues that Luther and the Lutherans raised through the Reformation period. I hope you will join me as we remember the great theological (re)discoveries that were made during this period.

Indulgences are Worse than Useless

Luther’s critique of indulgences was a typical (for him) combination of insight and invective. He sought to clearly condemn not just the sale of but also the use of indulgences, which means parts of his critique remain quite relevant today. Here we will draw primarily from Luther’s explanations of his 95 theses.

Luther argued that the pope actually has no power over purgatory and, moreover, that if the pope did have this power, he ought to exercise it:

If the pope does have the power to release anyone from purgatory, why in the name of love does he not abolish purgatory by letting everyone out? (81-82, cited below)

The question cuts straight to he heart of the system in which the pope is exalted as having power over souls in purgatory. It is clear that Luther did not at this point denounce the doctrine of purgatory. What his point is directed at instead, is the claim that the pope does have such power. After all, if the pope does have such power, then why would he not simply release all the souls from purgatory immediately, thus granting a most generous and wonderful reprieve? The fact that the pope of Luther’s time did not do so and was in fact selling indulgences for coin spoke volumes about the doctrine itself and the need for reformation.

But the point still has relevance today, as one might ask the question: if the pope today currently has the power over purgatory, why does he not simply release all those who are suffering there? One possible answer might be because it is just that people undergo such suffering or bettering of themselves in purgatory that they might truly be, er, reformed. But then the question of the two kingdoms comes to mind. After all, such a response effectively strips the pope of the power that has allegedly been granted him, for if the spiritual benefits of purgatory are so great, why does he ever exercise the power he is said to hold? The argument can proceed indefinitely in a circle, which seems to show that the initial point is valid.

Luther, however, did not stop there. Rather than questioning the power of the pope to grant indulgences, he also noted the great spiritual harm such indulgences do:

Indulgences are positively harmful to the recipient because they impede salvation by diverting charity and inducing a false sense of security… Indulgences are most pernicious because they induce complacency and thereby imperil salvation. Those persons are damned who think that letters of indulgence make them certain of salvation. (82)

Indulgences, by granting pardon from sin or the consequences thereof, produce a false sense of security of salvation that may lead rather to damnation. For once one believes that because someone else has told them future or past sins are paid for by some collection of merit of others, they may believe that they are forgiven, when they have not confessed and repented of that sin to God. Thus, a false sense of security is gained, but in reality the person may be condemned, not having received full and free forgiveness of their sins.

Links

Be sure to check out the page for this site on Facebook and Twitter for discussion of posts, links to other pages of interest, random talk about theology/philosophy/apologetics/movies and more!

Please check out my other posts on the Reformation:

I discuss the origins of the European Reformations and how many of its debates carry on into our own day.

The notion of “sola scriptura” is of central importance to understanding the Reformation, but it is also hotly debated to day and can be traced to many theological controversies of our time. Who interprets Scripture?

The Church Universal: Reformation Review– What makes a church part of the Church Universal? What makes a church part of the true church? I write on these topics (and more!) and their origins in the Reformation.

The Continuing Influence of the Reformation: Our lives, our thoughts, our theology– I note the influence that the Reformation period continues to have on many aspects of our lives.

Source

Quotes from Luther are from Roland Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (New York: Abingdon, 1950). It appears as though Bainton was either translating directly from a German edition or paraphrasing Luther.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.