relativism

Book Review: “Why It Doesn’t Matter What You Believe If It’s Not True” by Stephen McAndrew

Is there absolute truth? Such is the topic of Stephen McAndrew’s new book, Why It Doesn’t Matter What You Believe If It’s Not True (hereafter DMYB).

Is there absolute truth? Such is the topic of Stephen McAndrew’s new book, Why It Doesn’t Matter What You Believe If It’s Not True (hereafter DMYB).

McAndrew begins the work by noting that his book is an examination of a position and an affirmation of absolute truth. This is done because it is important to “examine even the most comfortable beliefs and leave standing only those that survive the disciplined assault of reason” (9).

He begins this testing by exploring some philosophical background, from Plato to positivism to relativism. These summaries are succinct, but provide a great background for those who haven’t read much on the topic. He turns next to a discussion of the effects of an abandonment of absolute truth. Relativism divorces one from any capacity to judge right and wrong. McAndrew notes, “These actions [such as the holocaust, racism, etc.] may brutally offend our sense of right and wrong, but the moral relativist cannot apply his or her values to others” (27).

What is interesting, however, is that McAndrew doesn’t stop at discussing relativism alone, but rather a conjunction of two beliefs: relativism and universal human rights. Many people, McAndrew notes, hold to relativism but also want to affirm universal human rights. In DMYB, he uses the discussion of the Nuremberg Tribunals–at which Nazis were tried for war crimes–as a case study for these conflicting views. He notes that “The defendants at Nuremberg argued that international law could only punish states and not individuals…. The Nuremberg court held that individuals could be punished for crimes against humanity under international law” (34).

Relativists, however, cannot consistently agree with the Nuremberg court, because “If there are no absolute truths, there can be no universal human rights” (35). These rights, if relative, are “contingent upon our cultural and historical position…” (ibid).

But relativism has a worse problem–it is contradictory. If all truth is contingent, then the statement “All truth is relative” is also relative, and therefore cannot be true for all people in all places (43ff). McAndrew next turns to the source for the “human rights urge”–the notion that all humans have certain universal rights. This source, argues McAndrew, is God (62ff). He makes a final case study when he turns to art–if there is no absolute truth, then there is no enduring beauty or truth in art (77ff).

The strengths of McAndrew’s book are readily apparent. He does a great job explaining difficult philosophical topics with terms and examples that anyone can understand. Not only that, but his discussion of Wittgenstein and the book 1984 give concrete, workable topics for those interested in the topic to use as talking points. My only criticism is that I believe I found a minor error. On page 85 McAndrew refers to the law of the excluded middle as the law that “propostion A and its direct contradiction–proposition B–cannot both be true at the same time.” This is in fact the law of noncontradiction. The law of the excluded middle is “For any proposition, it is either the case that the proposition is true or its negation is true.” This is a minor quibble, and one can derive the law of noncontradiction from the law of the excluded middle, but I thought I should note it.

Overall, the book may not convince everyone that there is absolute truth, but it will certainly force them to think about the positions they hold and wonder whether they can consistently cling to a relative absolutism. Those who already own a few books on the topic may wonder whether it is worth adding to their collection. Simply put, yes it is, if only to have at hand some great specific examples and talking points to discuss with relativists. It’s also a quick read that can be handed out to friends to open up the path for future discussion. I highly recommend DMYB.

Source

Stephen McAndrew, Why It Doesn’t Matter What You Believe If It’s Not True (Sisters, OR: Deep River, 2012).

Disclaimer: I was provided a review copy of this book by the author. My thanks to Stephen for the opportunity to review his book.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Really Recommended Posts 01/26/12

Jump: Hiking the Transcendent Trail– I can’t describe how aesthetically pleasing this site is. But, apart from that, Anthony Weber outlines a basic argument from aesthetics towards the existence of God. I found this post really interesting and mind-opening. Check it out!

Jump: Hiking the Transcendent Trail– I can’t describe how aesthetically pleasing this site is. But, apart from that, Anthony Weber outlines a basic argument from aesthetics towards the existence of God. I found this post really interesting and mind-opening. Check it out!

Was Adolf Hitler a Better Man Than Martin Luther King, Jr.?– Relativism cannot make sense of moral heroes. Arthur Khachatryan makes an excellent argument towards this end here.

Maverick Philosopher: Why Do Some Physicists Talk Nonsense about Nothing?– A discussion of Lawrence Krauss’s position on the universe from “nothing.” [Warning: There are a few curse words here.]

My recent discussion of the moral argument had many up in arms about the fact that I didn’t explicitly defend its premises. [Note that that was never the intention of the post, as its title explicates.] Glenn Peoples has an excellent post defending P1 of the moral argument: that If God did not exist, there would not be any objective moral values or duties. Check out his “The conditional premise of the moral argument.”

Ehrman’s Problem: He Misreads the Bible and Impugns God’s Fairness– Clay Jones discusses a number of difficulties with Bart Ehrman’s interpretations of the Bible. Check out the entire series. Part 2: Free Will and Natural Evil Part 3: God Could Have Made Us So We’d Always Do Right Part 4: Why Don’t We Abuse Free Will in Heaven? Part 5: God Should Intervene More to Prevent Free Will’s Evil Use He’s Confused About the Free Will Defense

Alexander Vilenkin: “All the evidence we have says that the universe had a beginning.”- Discussion of reasons to hold the universe began based on cosmology.

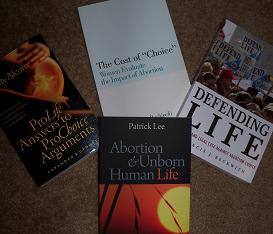

Abortion: The Struggle Between Objectivity and Subjectivity

I’ve noticed in the past that as I debate the moral issue of abortion, it seems as though people tend to ignore reason in lieu of emotional appeals. Upon further examination of the issue, I am even more convinced that this is the case. But what is at the bottom of this appeal? Why is it that something which must have an objective answer is treated like subjective, lukewarm hogwash? The reason, I believe, is because the issue of abortion is involved in the overarching debate of subjective (relative) versus objective ethical theories.

I’ve noticed in the past that as I debate the moral issue of abortion, it seems as though people tend to ignore reason in lieu of emotional appeals. Upon further examination of the issue, I am even more convinced that this is the case. But what is at the bottom of this appeal? Why is it that something which must have an objective answer is treated like subjective, lukewarm hogwash? The reason, I believe, is because the issue of abortion is involved in the overarching debate of subjective (relative) versus objective ethical theories.

What reasons do I have for making this claim? First, we must examine the most prominent pro-choice arguments. Pro-choice arguments generally fall into two broad categories:

1) Devaluing the fetus

2) Pointing towards the value of personal choice/control over one’s own body

Now, 1) fails miserably on a number of logical and scientific levels. See my other posts on the topic for discussions of these reasons (notably, this post and this one). But if 1) is rejected, then 2) may be the only way for pro-choice advocates to argue for their position. Unfortunately, 2) boils down to a kind of subjectivism about morality which ends up being self-defeating.

I am reminded of the echoing catch-phrase popular with politicians, “I am pro-choice, but against abortion.” What does this mean? Often, those who say such things generally mean that whatever someone else wants to do is fine with them. We shouldn’t try to limit the choices others make. We don’t have any reason to regulate what choices someone else can make or can’t make. And sure, I think abortion is wrong, but what right do I have to force my morality on others?

Initially, such arguments seem to make intuitive sense. The problem is that while the argument is trying to avoid forcing any “ought” statements, it has one huge “ought” planted right in the middle of its train of thought. That is, that “We ought not limit the choices of others.” But why should this be the case? There are certainly a huge number of cases in which I would limit the choices of others. Rape, for example, would be one instance where I would say this choice is not to be allowed. Perhaps the argument could be modified, then, and say that as long as one’s choice doesn’t harm anyone else, we ought not limit it. But then this pushes the burden of proof back onto argument 1), which is becoming ever more difficult for the pro-choice advocate to uphold.

Not only that, but having an “ought” statement like any of those above goes exactly contrary to what such statements are asserting. What if I choose to disagree with the statement that we “ought not limit the choices of others”? Should my choice to disagree be limited?

Furthermore, what reasons are their to argue that one should have absolute and total control over one’s own body? For if we do think that this is the case, we should then cease efforts in trying to limit substance abuse, cutting, anorexia, suicide, bulimia, and the like! These are all cases in which someone is simply making choices about his/her own body! If I want to cut myself, that should be my choice! If I want to starve myself, that should be my choice!

No, the bottom line is that the pro-choice camp wants to advocate total relativism. On this view, that which is ethically right for one person is okay for that person. There are innumerable difficulties with such a view (I’ve only touched on these above).

Thus, it seems to me that the pro-choice advocate has insurmountable difficulties with his or her position. First, this view cannot accurately measure when one’s “personhood” begins objectively. Second, it desires to claim an objective “ought” statement which ultimately defeats itself. Third, it runs contrary to scientific advances in measuring the stages of life of the human. Fourth, it stands on shift philosophical soil, for it is unable to accurately define “personhood” in any sufficient manner.

Thus, I conclude, as I’ve done so many times before, that to be pro-abortion is to hold a view that is positively irrational.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author.