philosophy of religion

Debate Review: Greg Bahnsen vs. Gordon Stein

Advocates of the presuppositional approach to Christian Apologetics have long hailed the debate between Greg Bahnsen (the late Christian theologian and apologist, noted for his achievements in presuppositional apologetics and development of theonomy–a view of the Law for Christians, pictured left) and Gordon Stein (the late secularist noted for his links to Free Inquiry among other things, pictured below, right) as a stirring triumph of presuppositional apologetics over atheism in a point-by-point debate. Recently, I listened to the debate and thought I would share my impressions here.

Advocates of the presuppositional approach to Christian Apologetics have long hailed the debate between Greg Bahnsen (the late Christian theologian and apologist, noted for his achievements in presuppositional apologetics and development of theonomy–a view of the Law for Christians, pictured left) and Gordon Stein (the late secularist noted for his links to Free Inquiry among other things, pictured below, right) as a stirring triumph of presuppositional apologetics over atheism in a point-by-point debate. Recently, I listened to the debate and thought I would share my impressions here.

Debate Outline

Bahnsen Opening Statement

From the outset, it was clear this debate was going to be different from others I’d listened to or watched. Bahnsen outlined what he means by “God,” outlined a few general points about subjectivism, and then quickly dove into a presuppositional type of argument. He began with an attack on the idea that all existential questions can be answered in the same way:

The assumption that all existence claims are questions about matters of fact, the assumption that all of these are answered in the very same way is not only over simplified and misleading, it is simply mistaken. The existence, factuality or reality of different kinds of things is not established or disconfirmed in the same way in every case. [All quotes from the transcript linked below. My thanks to “The Domain for Truth” for linking this.]

Bahnsen then mounts an argument which is perhaps the most important innovation of presuppositional apologetics: the attack on neutrality. He notes that Gordon Stein in his writings puts forth a case for examining evidence in order to determine if God exists. He relies upon the laws of logic and seems to think that this avoids logical fallacies. Yet, Bahnsen argues, Stein has just argued in a circle as well. By presupposing the validity of the laws of logic and other forms of reasoning, he has fallen into the trap he has stated he is trying to avoid. As such, Stein’s outlook is not neutral but it is colored by his presuppositions. Bahnsen notes:

In advance, you see, Dr. Stein is committed to disallowing any theistic interpretation of

nature, history or experience. What he seems to overlook is that this is just as much begging the question on his own part as it is on the part of the theists who appeal to such evidence. He has not at all proven by empirical observation and logic his pre commitment to Naturalism. He has assumed it in advance, accepting and rejecting all further factual claims in terms of that controlling and unproved assumption.Now the theist does the very same thing, don’t get me wrong. When certain empirical

evidences are put forth as likely disproving the existence of God, the theist regiments his

commitments in terms of his presuppositions, as well.

Therefore, what Bahnsen presses is that it is only on the Christian theistic presupposition that things like the laws of logic, the success of empirical sciences, and the like can make sense. He makes the transcendental argument for the existence of God:

we can prove the existence of God from the impossibility of the contrary. The transcendental proof for God’s existence is that without Him it is impossible to prove anything.

Gordon Stein Opening Statement

Stein opens by clarifying what he means by “atheist”: “Atheists do not say that they can prove there is no God. Also, an atheist is not someone who denies there is a God. Rather, an atheist says that he has examined the proofs that are offered by the theists, and finds them inadequate.”

Stein opens by clarifying what he means by “atheist”: “Atheists do not say that they can prove there is no God. Also, an atheist is not someone who denies there is a God. Rather, an atheist says that he has examined the proofs that are offered by the theists, and finds them inadequate.”

Stein then argues that the burden of proof is definitely in the theist’s court. He goes on to address a number of theistic proofs and finds them wanting. In fact, the rest of his opening statement is spent addressing 11 separate arguments for the existence of God, including the major players like the moral, cosmological, and teleological arguments.

Cross Examination 1

In the first cross-examination, Bahnsen asked Stein whether the laws of logic were material or immaterial. Stein finally, quietly, admits that the laws of logic are not material. Yet then Stein turns around and in his own cross examination presses triumphantly a point he thinks will be decisive. He asks Bahnsen, “Is God material or immaterial”; Bahnsen responds, “Immaterial.”; after a brief segway, Stein poses the following question which, by the tone of his voice, he seems to think carries some weight: “Apart from God, can you name me one other thing that is immaterial?” To this question, Bahnsen responds quickly, “The laws of logic.” The crowd erupts. Stein lost that one.

First Rebuttal: Bahnsen

Bahnsen spends most of his rebuttal arguing that the laws of logic are not mere conventions, and that Stein cannot make them such. If Stein does, then, argues Bahnsen, he can’t actually participate in a logical debate, because they could each declare a convention in which they each win the debate.

He goes on to re-stress the transcendental argument and point out that Stein failed to address it. He develops it a bit further by attacking the notion that an atheistic worldview can make sense of logic:

And that’s because in the atheistic world you cannot justify,you cannot account for, laws in general: the laws of thought in particular, laws of nature,cannot account for human life, from the fact that it’s more than electrochemical complexesin depth, and the fact that it’s more than an accident. That is to say, in the atheist conceptionof the world, there’s really no reason to debate; because in the end, as Dr. Stein has said, allthese laws are conventional. All these laws are not really law-like in their nature, they’re just,well, if you’re an atheist and materialist, you’d have to say they’re just something that happensinside the brain.

But you see, what happens inside your brain is not what happens inside my brain.

Stein First Rebuttal

Stein argues that laws of logic are indeed conventions, saying:

The laws of logic are also consensuses based on observations. The fact that they can predict something correctly shows they’re on the right track, they’re corresponding to reality in some way.

Oddly, Stein continues to act as though Bahsnen’s argument was a variety of cosmological argument. He argues that before we can ask “what caused the universe” we must ask whether the universe is actually caused. He then tries to address the argument more explicitly, saying that it is “nonsense” and that various cultures do indeed have different logic. His most direct argument against the trasncendental argument is that “If matter has properties that it behaves than we have order in the universe, and we have a logical, rational universe without God.”

Debate Segment Two

Stein Opening 2

Stein argues that the problem of evil is an evidential argument against the existence of God. He states that it raises the probability that there is no God. He asserts that there is no physical evidence for God. Stein then argues that God has not provided evidence for his existence, but that He should do so. Finally, he turns to the problem of religious diversity, asking why God would allow other religions if there is only one God.

Bahnsen Opening 2

Bahnsen argues that Stein placing the laws of logic into a matter of consensus undermines their usefulness and in fact defeats the purpose of rational inquiry and debate. He argues further that Stein’s definition of laws of logic within pragmatic terms doesn’t come close to the extent of the laws of logic.

Stein Rebuttal

Stein argues that bahnsen hasn’t actually done anything to explain the laws of logic. He argues that simply saying they are the thoughts of God doesn’t mean anything, and that it does nothing to explain them. He therefore argues that Bahnsen fails to provide an adequate explanation for the facts of the universe.

Bahnsen Rebuttal

Bahnsen presses the point that Stein’s entire system is based upon presuppositions which he cannot justify. Induction is undermined in an atheistic worldview because there is no reason to believe that things will continue to happen as they do currently happen. He briefly addresses the problem of evil by saying that within an atheistic universe there simply is no evil, so it makes no sense from Stein’s perspective to press that issue.

Closing Statement: Stein

Stein’s closing statement seems to be more of a rebuttal than anything. He argues that there can be evil defined in an atheistic universe as that which decreases the happiness in people. Yet even this, he says, “We don’t know”–we don’t know that there is evil in an atheistic universe, rather it is a consensus and pragmatically useful.

He argues that we can know about induction because of statistical probability: it is highly improbable that the future will be different from the past because it has been similar in activity to the past for as long as we know.

Closing Statement: Bahnsen

Bahnsen finally presses the transcendental one last time. He argues that while Stein has called it hogwash and useless, he hasn’t actually responded to it. Bahnsen states that once more the atheistic worldview can’t make sense of itself. For example, saying the future will be like the past due to probability begs the question: there is nothing in the atheistic worldview to say that probability can help determine what the future will be like. It might work pragmatically, but it fails to give any explanation. Finally, Bahnsen argues that you cannot be a rational, empirical human being an an atheistic universe.

Analysis of the Debate

It is abundantly clear throughout this debate that the presuppositionalist takes a very different approach to debate and apologetics than those from other methods. One can see this immediately when Gordon Stein delivers his opening statement, which was presumably prepared beforehand, and goes to answer common theistic arguments like the cosmological and teleological argument. But Bahnsen never once used either of these arguments, and took an entirely different approach. I think this initially caught Stein off guard and that impression remained throughout the debate.

Stein’s responses to Bahnsen were extremely inadequate. This became very clear in their debate over induction and empiricism. For example, although Stein held that he could say the future will be like the past based upon probability, he had no way to say that the world was not spontaneously created 5 minutes ago with implanted memories and the notion that the future will be like the past. Bahnsen didn’t make this argument, but it seems like it would line up with his reasoning. Of course, he would grant that the theist has to presuppose that God exists in order to make sense of induction, but that was exactly his point: without God, nothing can be rational.

I found it really interesting that Stein kept insisting that the laws of logic are mere social conventions. He kept pressing that some cultures do not hold that they are true as defined. But of course, cultural disagreement about a concept doesn’t undermine the truth value of a concept. If, for example, there were a culture that insisted that 2+2=5, that wouldn’t somehow mean that 2+2=4 is a logical convention, it would mean the culture who insisted the sum was 5 would be wrong. Similarly, the laws of logic may be disagreed upon by some, but to deny them is to undermine all rationality.

Overall, I have to say I was shocked by how this debate turned out. I have long been investigating presuppositional apologetics and continually wondered how it would work in an applied situation. It seems to me that to insist on a presupposition in order to debate would not work, but Bahnsen masterfully used the transcendental argument to reduce Stein to having to argue that logic is merely a social convention while ironically using logic himself to attack theism.

It seems to me that this debate showed what I have suspected for some time: presuppositional apologetics is extremely powerful, when used correctly. Now I’m not about to become a full-blown presuppositionalist here. My point is that it is another approach Christians can use in their witnessing to those who do not believe. I envision a synthesis of presuppositional apologetics with evidentialism. Some may say this is impossible, that they are anathema to each other, but I do not think so. They can be used in tandem: the presuppositional approach to question the worldview of others, while the evidentialist approach can be used to support the notion that the Christian worldview provides the best explanation for the data we have.

Links

Listen to the debate yourself. Get it here. The transcript I used was also from this page. Thanks to the author for such a great resource.

I’ve been researching and writing about presuppositional apologetics. For other posts about presuppositional apologetics, check out the category.

I highly recommend starting with the introduction to the most important thinker in the area, Cornelius Van Til.

Choosing Hats– A phenomenal site which updates fairly regularly with posts from a presuppositional approach (the author uses the term “covenental apologetics”). The best place to start is with the post series and the “Intro to Covenental Apologetics” posts.

The Domain for Truth– Another great presuppositionalist web site. I highly recommend browsing the topics here.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

The Argument from Religious Experience: A look at its strength

I have written previously about the argument from religious experience. I provided a brief outline of the argument and commented on its usefulness. Now, I turn to the question of the strength of the argument from religious experience.

I have written previously about the argument from religious experience. I provided a brief outline of the argument and commented on its usefulness. Now, I turn to the question of the strength of the argument from religious experience.

[Note: Through this post, when I say “religious experience” I am referring to experience generally–that is, numinous, sensory, and the like. I will distinguish when I mean otherwise.]

The Sheer Numbers

Religious Experience is pervasive throughout human history. You can find accounts of it in the Upanishads, the Vedas, the Qur’an, the Torah, the Gospels, and more. Not only that, but recent, systematized studies have found that religious experience continues to be a part of people’s realm of experience.

Consider David Hay’s study, Religious Experience Today. The book is based upon a number of national and community surveys in the UK. For example, one Gallup poll in Britain in 1987 yielded a response rate of 48% of people saying they had had a religious experience as described by the poll. In 2000, another poll in the UK yielded a 36% positive response. Granted that some of this may be due to false positives, one must also realize that there is a kind of repression of expressing religious experience due to embarrassment and/or personal bias, so these numbers may also lean towards the lower end (Hay, 57ff).

One could also look at the sheer number of luminaries throughout all time who have claimed religious experience. Throughout the literature, such experiences are far too numerous to be restricted to a descriptor like “many.”

One can’t help but agree with Richard Swinburne, who wrote, “[T]he overwhelming testimony of so many millions of people to occasional experience of God must… be taken as tipping the balance of evidence decisively in favour of the existence of God” (Is There a God?, 120).

The Balance of the Scales

“The argument from religious experience” (hereafter ARE) is itself somewhat of a misnomer–there are many forms of arguments from religious experience, so it is helpful to clarify when one is in dialog which version one is using. I have noted elsewhere that the ARE comes in two varieties: one which argues for public belief and one which argues for personal justified belief. There are two more variants to introduce here: the broad version and the narrow version.

1. The Broad Version of the ARE presents religious experience as a general proof for either:

A) the existence of some transcendent realm–this being a transcendent aphysical realm. This is the broadest version of the argument.

B) the existence of God. This is a broader version of the argument, but isn’t as generalized as A).

2. The Narrow Version of the ARE argues for the truth of a particular religion based upon religious experience. Note that this is narrow in that many religions could affirm a “transcendent realm” or the existence of God[s], but if the argument is construed in this fashion, only the religion which is claimed to have superior evidence from religious experience is [fully] true. [Other religions could have many truths which could be affirmed through RE, but only one would have the “full” or “realized” truth.]

The argument from religious experience is much easier to defend if it is presented broadly. As one narrows the argument, one is forced to deal with potential defeaters from religious experiences which do not accord with the argument being made. For example, if one argues that God exists based upon religious experience, one would have to somehow contend with the great amount of evidence for monistic or Nirvanic religious experience.

The argument from religious experience is much easier to defend if it is presented broadly. As one narrows the argument, one is forced to deal with potential defeaters from religious experiences which do not accord with the argument being made. For example, if one argues that God exists based upon religious experience, one would have to somehow contend with the great amount of evidence for monistic or Nirvanic religious experience.

Think of the argument like as a bridge with a counterbalance or a scale with a counterbalance. The more weight one places on the argument [i.e. saying that it can justify the existence of God] (scale/bridge), the more one must deal with that weight on the other end (counterbalance).

If the argument is presented as a way to prove general transcendence of experience, it is extremely strong and very easy to defend. When one instead uses the argument to try to justify the truth claims of a specific religion, one then must come up with a mechanism for determining how to evaluate competing religious experiences. For example, if I argue that religious experiences prove Christianity to be true because so many people have experienced in sensory ways Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior, then it is my task to also show that the experiences of, say, Shiva as god are unwarranted. Thus, the philosopher’s task increases in difficulty the more narrowly he presents the arguments conclusion.

Consider the following two conclusions from arguments (granting me authorial privilege to assume that readers can plug in the premises): 1) Therefore, religious experience justifies the belief that there is a realm apart from our mere physical existence; 2) Therefore, religious experience serves as powerful evidence for the truth of Christianity. The fact that 2) is much more narrow means that one must do much more to show that the conclusion is justified.

Does this mean that the argument is useless when arguing for a particular religion? Certainly not. There are many who have used the ARE for a defense of Christianity specifically (cf. William Alston Perceiving God and Nelson Pike Mystic Union). What is important to note is that when one uses the argument in dialog they must be very aware of how they formulate the argument. As a “Broad/public” version, it can serve as powerful evidence in part of a cumulative case for Christianity; as a “narrow/private” version, it can be strong confirmation of the justification of one’s faith. These variants can be used together or separately.

The Strength of the Argument

So how strong is the ARE? I hope I don’t disappoint readers when I respond by saying: that depends! As far as my opinion is concerned, it seems to me that the “broad/public” and “broad/private” version of the argument are nearly irrefutable. I think it is an invaluable tool for apologists and philosophers of religion. The “narrow/private” or “narrow/public” versions of the argument are not as strong by necessity: they must contend with more objections as they narrow. However, as part of one’s own faith life, I think the “narrow/private” and “narrow/public” versions can give great comfort and solace.

[Author’s note: The next post on the argument from religious experience will defend the principle of credulity.]

Further Reading

See my “The Argument from Religious Experience: Some thoughts on method and usefulness“- a post which puts forward an easy-to-use version of the ARE and discusses its importance in apologetic endeavors.

The following books are all ones I have read on the topic but do not present a comprehensive look at literature on the subject.

Caroline Franks Davis, The Evidential Force of Religious Experience (New York, NY: Oxford, 1989). One of the best books on the topic, Franks Davis provides what I would see as a nearly comprehensive look at the epistemic defeaters to consider with the argument from RE.

Jerome Gellman, Experience of God and the Rationality of Theistic Belief (Ithaca, NY: Cornell, 1997). Gellman provides a robust defense of the principle of credulity.

Paul Moser, The Evidence for God (New York: NY, Cambridge, 2010). This work is not so much about the argument from RE as it is an argument showing that any evidence for God is going to be necessarily relational. I highly recommend it.

Richard Swinburne, Is There a God?(New York, NY: Oxford, 2010). This is an introductory work to Swinburne’s theistic arguments. It has a chapter on the argument from RE that provides an excellent, easy-to-read look at the issues surrounding the argument. I reviewed this book here.

There are a number of other fantastic books on the topic as well. Swinburne’s The Existence of God has a chapter that remains a classic for the defense of the argument from RE.

William Alston’s Perceiving God is perhaps one of the best examples of a robust epistemology built up around RE and realism.

Keith Yandell’s The Epistemology of Religious Experience is a extremely technical look at many of the issues, and I found it particularly useful regarding the notion of “ineffability” in RE.

Kai-man Kwan’s Rainbow of Experiences, Critical Trust, and God is a very recent look at the argument which again features a large amount of epistemological development.

Nelson Pike provides a unique look at the phenomenology of RE and a synthesis of theistic and monistic experiences in his work Mystic Union.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

The Argument from Religious Experience: Some thoughts on method and usefulness

The argument from religious experience (hereafter referred to as “argument from RE”) has seen a resurgence in scholarly work. Keith Yandell, Richard Swinburne, Jerome Gellman, Kai-man Kwan, Caroline Franks-Davis, Paul Moser, and others have contributed to the current discussion about the topic.

The argument from religious experience (hereafter referred to as “argument from RE”) has seen a resurgence in scholarly work. Keith Yandell, Richard Swinburne, Jerome Gellman, Kai-man Kwan, Caroline Franks-Davis, Paul Moser, and others have contributed to the current discussion about the topic.

One thing which has disappointed me on more than one occasion is the dismissive attitude that some Christian apologists show towards the argument from religious experience.

What reasons are there for apologists to adopt such a stance? Well it seems possible that some of them simply haven’t studied the argument enough to consider its plausibility. I admit that before interacting with the argument, I was skeptical of the possibility for its having any value. But I want to suggest another possibility: apologists tend to favor arguments which can be presented and defended in a debate format or which are useful in short conversations with others. I’m not suggesting this as an attack on my fellow Christians, merely as an observation. And this is not a bad thing; it is indeed greatly useful to have arguments which can be presented quickly and defended easily when one is trying to present a case for Christianity to others.

The problem is the argument from RE requires a great deal of epistemological background in order to get to the meat of it. The authors listed above each develop a robust epistemology to go with their argument. This seems to put a limit on the usefulness of the argument; if it must be conjoined with a broad discussion of epistemology, then how can one present it in such a way that those who aren’t professional philosophers (or at least interested in the topic) can understand? It is to this question I hope to present an answer.

Background Information

Formulations of the Argument

There are two primary ways the argument from RE can be formulated (Caroline Franks Davis suggests a number of ways the argument can presented in The Evidential Force of Religious Experience, 67-92). The first is the personal argument; the second is the public argument. Now I have seen very few versions of the former in the literature. The personal argument is essentially an argument from RE which centers not on trying to demonstrate the existence of God to others, but rather upon justifying one’s own belief that such an experience is genuine. In other words, the personal argument from RE focuses upon defending one’s own conviction that a religious experience is veridical.

Paul Moser, in his work The Evidence for God, suggests one possible way to formulate this argument [he does not refer to it in the same terminology as I use here]:

1. Necessarily, if a human person is offered and receives the transformative gift, then this is the result of the authoritative power of… God

2. I have been offered, and have willingly received, the transformative gift.

3. Therefore, God exists (200, cited below).

This argument is one example of what I would call the personal argument from RE. It focuses on one’s own experience and uses that to justify one’s belief in God. [It seems Moser could be arguing for this as a public argument as well, but a discussion of this would take us too far afield.]

A public argument from RE is generally formulated to establish the belief in God (or at least a transcendent reality), just as other theistic arguments are intended. It will best function as part of a “cumulative case” for the existence of God. One example of an argument of this sort can be found in Jerome Gellman, Experience of God and the Rationality of Theistic Belief:

If a person, S, has an experience, E, in which it seems (phenomenally) to be of a particular object, O… then everything else being equal, the best explanation of S’s having E is that S has experienced O… rather than something else or nothing at all (46, cited below).

Readers familiar with the literature on RE will note the similarities between this and Richard Swinburne’s principle of credulity. The basic idea is that if someone has an experience, then they are justified in believing they had that experience, provided they have no (epistemic) defeaters for that experience.

Brief Epistemological Inquiry

I’ve already noted the intricate ties the argument from RE has with epistemology, and a quick introduction to the argument would be remiss without at least noting this in more explicit detail. The core of establishing the argument from RE is to undermine methodological/metaphysical naturalism. Thus, a robust defense of the argument from RE will feature building up a case for an epistemological stance in which theistic explanations are not ruled out a priori.

A second step in this epistemological background is to establish a set of criteria with which one can judge and evaluate individual religious experiences. Caroline Franks Davis’ study (cited below) is a particularly amazing look into this tactic; she explores a number of possible defeaters and criteria for investigating REs. These range any where from hallucinogenic drugs to the multiplicity of religious experience.

The Force of the Evidence

One concern I had when I was exploring the argument from RE is that it would not have very much force. Upon investigating the topic, however, I can’t help but think the force of the argument is quite strong. Swinburne seems correct when he writes, “[T]he overwhelming testimony of so many millions of people to occasional experience of God must… be taken as tipping the balance of evidence decisively in favour of the existence of God” (Swinburne, Is There a God?, 120, cited below). The important thing to remember is that an overwhelming number of people from all stations of life and cultures have had experiences that they deem to be “spiritual” or hinting at “transcendence.” Denying universally all of these experiences as genuine would seem to require an enormous amount of counter-evidence.

A Suggested Version for Quick Discussion

So what to do with this background knowledge? It seems to me it is possible to at least sketch out a version of the argument from RE for a brief discussion, with a defense. Further reading is provided below.

The Argument Stated

1. Generally, when someone has an experience of something, they are within their rational limits to believe the experience is genuine.

2. Across all socio-historical contexts, people have had experiences of a transcendent realm.

3. Therefore, it is rational to believe there is a transcendent realm.

The argument made more explicit

The reason I suggest this as the way to use the argument from RE in a brief discussion is because it can more easily form part of a cumulative case and requires less epistemological work to justify it. The first premise is, in general, a principle of rationality. While there are many who have attacked Swinburne’s principle of credulity, it does seem that we generally affirm it. If I experience x, then, provided I have no reasons to think otherwise, I should believe that x exists/was real/etc.

The second premise is the result of numerous studies, some of which are cited in the works cited below. To deny this nearly universal experience is simply to deny empirical evidence. People like William James have observed this transcultural experience of the transcendent for hundreds of years.

Thus, it seems that we are justified in being open to the existence of things beyond the mundane, everyday objects we observe in the physical reality. If people from all times and places have had experiences of things beyond this everyday existence, then it does not seem irrational to remain at least open to the possibility of such things existing.

The conclusion may come as something of a letdown for some theists. But I would like to reiterate that this is a version of the argument intended for use in a brief conversation. There are versions of the argument in the cited literature below which defend theism specifically and engage in synthesis of these experiences into the theistic fold. What I’m trying to do here is make the argument part of the apologist’s arsenal. If we can use the argument merely to open one up to the reality of the transcendent, then perhaps they will be more open other theistic arguments. As part of a cumulative case, one can’t help but shudder under the overwhelming weight of millions of experiences.

Conclusion

The argument from religious experience has enjoyed a resurgence in scholarly popularity. A number of books from publishers like Oxford University Press, Cornell, and Continuum have reopened the argument to the scholarly world. It is high time that Christian apologists put in the work needed to utilize these arguments in everyday, accessible apologetics. The argument formulated above is just one way to do this, and Christians would do well to explore the argument further. The experience of God is something not to be taken lightly; Christians throughout our history have had such experiences and been moved into intimate relationships with God. We should celebrate these experiences, while also realizing their evidential value.

Further Reading and Works Cited

The following books are all ones I have read on the topic but do not present a comprehensive look at literature on the subject.

Caroline Franks Davis, The Evidential Force of Religious Experience (New York, NY: Oxford, 1989). One of the best books on the topic, Franks Davis provides what I would see as a nearly comprehensive look at the epistemic defeaters to consider with the argument from RE.

Jerome Gellman, Experience of God and the Rationality of Theistic Belief (Ithaca, NY: Cornell, 1997). Gellman provides a robust defense of the principle of credulity.

Paul Moser, The Evidence for God (New York: NY, Cambridge, 2010). This work is not so much about the argument from RE as it is an argument showing that any evidence for God is going to be necessarily relational. I highly recommend it.

Richard Swinburne, Is There a God?(New York, NY: Oxford, 2010). This is an introductory work to Swinburne’s theistic arguments. It has a chapter on the argument from RE that provides an excellent, easy-to-read look at the issues surrounding the argument. I reviewed this book here.

There are a number of other fantastic books on the topic as well. Swinburne’s The Existence of God has a chapter that remains a classic for the defense of the argument from RE.

William Alston’s Perceiving God is perhaps one of the best examples of a robust epistemology built up around RE and realism.

Keith Yandell’s The Epistemology of Religious Experience is a extremely technical look at many of the issues, and I found it particularly useful regarding the notion of “ineffability” in RE.

Kai-man Kwan’s Rainbow of Experiences, Critical Trust, and God is a very recent look at the argument which again features a large amount of epistemological development.

Nelson Pike provides a unique look at the phenomenology of RE and a synthesis of theistic and monistic experiences in his work Mystic Union.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Learning to Jump Again” by Anthony Weber

Anthony Weber’s work, Learning to Jump Again, is part memoir of a lost father, part philosophical treatise on the problem of suffering. The focus throughout is Weber’s father and the issues with mourning, suffering, and heroism his life and death brought up.

Anthony Weber’s work, Learning to Jump Again, is part memoir of a lost father, part philosophical treatise on the problem of suffering. The focus throughout is Weber’s father and the issues with mourning, suffering, and heroism his life and death brought up.

The book starts with “the Journal”–a series of entries from Weber’s journal during the time surrounding the death of his father. As one who is very close to his father, these entries truly struck home. There were many moments where this reader just lost it in tears. Weber does not hold back, at all. His father was suffering from jaundice due to cancer. He writes, “A friend stopped by that weekend to borrow some tools, and I stammered through an explanation of why my visiting father was yellow… He [the friend] knew that after the fall comes winter, and after the chill comes the cold, and he was mercifully silent” (2).

Weber does not restrict the period of mourning or the discussion thereof to the months immediately surrounding his father’s death; rather, the Journal contains entries as far as eight years (and later) after his father’s death. Christians reading the book are forced to the realization that it is not easy to struggle through these issues. When a beloved father dies, it is not something that passes with the seasons. Even eight years later, he wrote of his withholding himself from his wife and children, and the realization that came with it that he must trust in God, “even if I don’t always understand him” (76-78).

Yet the journal section is not merely a reflection. Weber shares lessons and thoughts he has on mourning, God, and the reality of pain in the world throughout his memoirs. He notes that too many people know about God without knowing God (72-73); refers to the experiences of wrestling God (45); and contrasts the ways and beliefs of “the flesh” with that of reality (33). Throughout this section, there is much for readers to take away.

The second part of the book focuses on the issues behind suffering and the Christian worldview. Weber’s discussion is an admirably easy-to-read introduction to many of the philosophical issues surrounding the problem of evil and other issues. In particular, his discussions of emotions, dreams, and prayer in particular offered a number of insights that readers will be interested in reading more about. Weber included a lot of resources for interested readers to explore, so the book serves as a valuable resource in that regard as well. His discussion of the problem of pain does an excellent job introducing difficult notions like distinguishing between types of the problem of evil (122ff). His discussion of the various possible routes theists can take to discuss the problem of evil is also brief but informative.

Throughout the book there are numerous quotes from various authors. Many of these are novelists such as J.R.R. Tolkien, Dean Koontz, Shakespeare, and C.S. Lewis. Others are from people like Helen Keller, Phillip Yancey, and Scripture. These quotes are often profound and fit the context perfectly. As a reader, this reviewer admits to frequently skimming past quotes when I see them in texts, particularly when they are out of context, but with Learning to Jump Again, the quotes all draw out new emotions, thoughts, and ideas very well. They add to, rather than distract from, the text.

Learning to Jump Again was a bit of a surprise for me. The section of the book that was a memoir served poignantly to draw readers into the heart of a mourning man. But it did not leave readers with that; rather, Weber constantly struggled with issues that Christians at all stages must deal with. Further, the philosophical section which encompassed the latter part of the book is an excellent survey of a number of issues. Many will benefit from the insights Weber provides. The book tugs at the heart strings and gets the mind working. Readers who have already extensively explored the issues of the latter part of the book will benefit from viewing the issues in the context of a memoir. Those who have not will benefit greatly from the discussion throughout the book. I recommend it very highly.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Where the Conflict Really Lies” by Alvin Plantinga

There are few names bigger than Alvin Plantinga when it comes to philosophy of religion and there are few topics more hotly debated than science and religion. Plantinga’s latest book, Where the Conflict Really Lies

There are few names bigger than Alvin Plantinga when it comes to philosophy of religion and there are few topics more hotly debated than science and religion. Plantinga’s latest book, Where the Conflict Really Lies (hereafter WCRL) has therefore generated much interest as it has one of the foremost philosophers of religion taking on this highly contentious topic.

Plantinga minces no words. The very first line of the book outlines his central claim: “there is superficial conflict but deep concord between science and theistic religion, and superficial concord and deep conflict between science and naturalism.”1

The first part of the book is dedicated to the superficial conflict between science and religious belief. The reason this alleged conflict is important is due, largely, to the success of the scientific enterprise. Because science has shown itself to be a reliable way to come to know the world, if religion is in direct conflict with science, then it would seem to discredit religion. Not only that, but, Plantinga argues, Christians should have a “particularly high regard” for science due to the foundations of the scientific enterprise on a study of the world.2

In order to examine this alleged conflict, Plantinga first takes on the article of science most often taken to discredit religion: evolution. Here, readers may be surprised to find that Plantinga does not try to argue against evolution itself. Rather, Plantinga draws a distinction between the notion of evolution and Darwinism. The former, argues Plantinga, is consistent with Christian belief, whether or not it is the way the variety of life came to be, while the latter is not consistent with Christianity because central to its account is the notion that the process of evolution is unguided.3

WCRL then turns to Richard Dawkins. Plantinga argues that “A Darwinist will think there is a complete Darwinian history for every contemporary species, and indeed for every contemporary organism.”4 Here again there is nothing which puts such a theory in conflict with Christian belief. Writes Plantinga, “[The process of evolution] could have been superintended and orchestrated by God.”5 But Dawkins (and others) claim that evolution “reveals a universe without design.” But what argument is provided towards this conclusion? Plantinga draws out Dawkins reasoning and shows that the only logic given is that evolution could have happened by way of unguided evolution. But then:

What [Dawkins] actually argues… is that there is a Darwinian series of contemporary life forms… but [this series] wouldn’t show, of course, that the living world, let alone the entire universe, is without design. At best it would show, given a couple of assumptions, that it is not astronomically improbable that the living world was produced by unguided evolution and hence without design. But the argument form ‘p is not astronomically improbable’ therefore ‘p’ is a bit unprepossessing… What [Dawkins] shows, at best, is that it’s epistemically possible that it’s biologically possible that life came to be without design. But that’s a little short of what he claims to show.6

Plantinga then moves on to argue that Daniel Dennett’s argument is similarly flawed.7 Paul Draper’s argument that evolution is more likely on naturalism than theism is more interesting, but assumes that “everything else is equal.”8 But then, everything is not equal. Theism provides a number of relevant probabilities which weigh the argument in favor of theism instead.9

The arguments against theism from evolution are therefore largely dispensed. What of the possibility of divine action? Some argue that God doesn’t actually act in the world—in fact, the argument is made that even most theologians don’t believe this, despite writing that God does act in various ways. The argument is made that because of natural laws, God cannot or does not intervene.10 However, one can simply argue that the correct view of a natural law is that “When the universe is causally closed (when God is not acting specially in the world), P.”11

Plantinga does acknowledge that there are some fields in science which do provide at least superficial conflict with theism. These include evolutionary psychology and (some) historical critical scholarship.12 Evolutionary psychology generally doesn’t challenge religious belief. “Describing the origin of religious belief and the cognitive mechanisms involved does nothing… to impugn its truth.”13 Now some suggest that religious beliefs are due to devices not aimed at truth, and this would provide a reason to doubt religious belief.14 However, the way that most do this is by conjoining atheism with psychology or operating under other assumptions which undermine religious belief a priori. While this may mean that specific conclusions in psychology are in conflict with theism, these conclusions only follow from the anti-theistic assumptions at the bottom. Thus, while some accounts of evolutionary psychology are in conflict with theism, they don’t provide a solid basis for rejecting it.15 Similarly, varied methods of historical concept may draw some conclusions which are in conflict with Christian theism, but these methods are themselves undergirded by assumptions that theism is, at best, not to be entered into historical discussion.16

There are, Plantinga argues, significant reasons to think that theism is in concord with science. First, the argument from cosmological fine-tuning, he argues, gives “some slight support” for theism.17 The section on fine-tuning has responses to some serious criticisms of such arguments. Most interesting are his responses to Tim and Lydia McGrew and Eric Vestrup—in which Plantinga argues that we can indeed get to the point where we can assess the fine-tuning argument;18 Plantinga’s discussion of the multiverse;19 and his discussion of relevant probabilities regarding fine-tuning.20

Michael Behe’s design theory is discussed at length in WCRL.21 Plantinga offers some additional insights into the Intelligent Design debate. He argues that one can view design not so much as a probabilistic argument but instead as simple perception.22 He reads both Behe and William Paley in this light and argues that they are offering design discourses as opposed to arguments.23 This, in turn, allows him to argue that design is a kind of “properly basic belief” and he offers a robust discussion of epistemology to support this intuition.24

Further, there is deep concord between Christian Theism and Science when one looks at the very roots of the scientific endeavor. Here, rather than simply listing various theists who helped build the empirical method, Plantinga argues that science relies upon various theistic assumptions in order for its methods to succeed. These include the “divine image” in which humans are capable of rational thought;25 God’s order as providing regularity for the universe;26 natural laws;27 mathematics;28 induction;29 and simplicity and “other theoretical virtues” (like beauty).30

Finally, Plantinga turns to naturalism: does it really resonate so well with science? Plantinga grants for the sake of argument that there is at least superficial concord between naturalism on science, if only because so many naturalists trumpet this “fact.”31 Yet there is, he argues, a deep conflict between science and naturalism: namely, that if evolution is true and naturalism is true, there is no reason to trust our cognitive abilities.32 “Suppose you are a naturalist,” he writes, “you think there is no such person as God, and that we and our cognitive faculties have been cobbled together by natural selection. Can you then sensibly think that our cognitive faculties are for the most part reliable?”33

Plantinga argues you cannot. The reason is because we have no way to suppose that evolution is truth aimed, but rather it is merely survival aimed (if indeed it is aimed at all!). He also argues that because naturalists are almost all materialists, there is no way to adequately ground beliefs.34 Finally, because naturalism and evolution conjoin to give a low probability that our rational abilities are reliable, we have received a defeater for every belief we have, including naturalism and evolution.35 Thus, the conflict “is not between science and theistic religion: it is between science and naturalism. That’s where the conflict really lies.”36

WCRL covers an extremely broad range of topics, and will likely be critiqued on each topic outlined above and more. The book touches on issues that are at the core of the debate between naturalists and theists, and as such it will be highly contentious. That said, the book is basically required reading for anyone interested in this discourse. Plantinga provides extremely valuable insights into every topic he touches. His discussion of biological design, for example, provides unique insight into the topic by locating it within epistemology as opposed to biology alone. Further, his “evolutionary argument against naturalism” continues to live despite endless criticism. The list of important topics Plantinga illumines in WCRL is extensive.

Where the Conflict Really Lies will resonate deeply with those who are involved in the science and religion discourse. Theists will find much to think about and perhaps new life for some arguments they have tended to set aside. Naturalists will discover a significant challenge to their own paradigm. Those on either side will benefit from reading this work.

——

1 Alvin Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies (New York, NY: Oxford, 2011), ix.

2 Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies, 3-4. (Unless otherwise noted, all references are to this work.)

3 12 (emphasis his).

4 15 (emphasis his).

5 16.

6 24-25.

7 33ff, esp. 40-41.

8 53.

9 53ff.

10 69ff.

11 86, see the arguments there and following.

12 129ff.

13 140.

14 141ff.

15 143ff.

16 152ff.

17 224.

18 205-211.

19 212ff.

20 219ff.

21 225-264.

22 236ff.

23 240-248.

24 248ff; see esp. 253-258, 262-264.

25 266ff.

26 271ff.

27 274ff.

28 284ff.

29 292ff.

30 296ff.

31 307ff.

32 311ff.

33 313.

34 318ff.

35 339ff.

36 350.

This review was originally posted at Apologetics315 here: http://www.apologetics315.com/2012/02/book-review-where-conflict-really-lies.html

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

The Ontology of Morality: Some Problems for Humanists and their friends

Louise Anthony did indeed present the case for secular metaethics. The problem is that this case is utterly vacuous.

It will be my purpose in the following arguments to show that secular humanistic theories which try to ground moral ontology fail–and fail miserably.

Recently, I listened [again] to the debate between William Lane Craig and Louise Anthony. Some have lauded this debate as a stirring victory for secular ethics. (See, for example, the comments here–one comment even goes so far as to say “I swoon when someone evokes the Euthyphro Dilemma and frown at the impotent, goal-post-moving, ‘Divine nature’ appeal.”) In reality, I think Louise Anthony did indeed present the case for secular metaethics. The problem is that this case is utterly vacuous.

I’ll break down why this is the case by focusing upon three areas of development in secular and theistic ethics: objective moral truths, suffering, and moral facts.

Objective Moral Truths

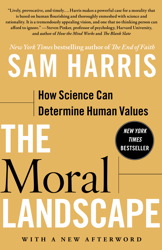

Louise Anthony and William Lane Craig agree that there are objective moral truths. Now, this is important because many theists take the existence of objective morality to demonstrate–or at least strongly suggest–the existence of God. Interestingly, other humanist/secular scholars have agreed with Anthony, claiming there are objective truths (another example is Sam Harris–see my analysis of his position contrasted with theism here). The question, of course, is “How?” Consider the following:

Louise Anthony seems to be just confused about the nature of objective morality. She says in response to a question from the audience, “The universe has no purpose, but I do… I have lots of purposes…. It makes a lot of difference to a lot of people and to me what I do. That gives my life significance… The only thing that would make it [sacrificing her own life] insignificant would be if my children’s lives were insignificant. And, boy you better not say that!”

Craig responded, “But Louise, on atheism, their lives are insignificant.” Anthony interjected, “Not to me!”

But then she goes on to make this confused statement, “It’s an objective fact that they [her children] are significant to me.”

Note how Anthony has confused the terms here. Yes, it is an objective fact that according to Louise Anthony, her children matter to her. We can’t question Anthony’s own beliefs–we must trust what she tells us unless we have reason to think otherwise. But that’s not enough. What Craig and other theists are trying to press is that that simple fact has nothing to do with whether her children are actually valuable. Sure, people may go around complaining that “Well, it matters to me, so it does matter!” But that doesn’t make it true. All kinds of things can matter to people, that doesn’t mean that they are ontologically objective facts.

It matters to me whether the Cubs [an American baseball team] win the World Series. That hasn’t happened in 104 years, so it looks like it doesn’t matter in the overall scheme of the universe after all. But suppose I were to, like Anthony, retort, “But the Cubs matter to me! It’s an objective fact that them winning the World Series is significant to me!” Fine! But all the Cardinals [a rival team] fans would just laugh at me and say “SO WHAT!?”

Similarly, one can look at Anthony with incredulity and retort, “Who cares!?” Sure, if you can get enough people around Anthony who care about her children’s moral significance, you can develop a socially derived morality. But that’s not enough to ground objective morality. Why should we think that her values matter to the universe at large? On atheism, what reason is there for saying that her desires and purposes for her children are any better than my desires and purposes for the Cubs?

Another devastating objection can be found with a simple thought experiment. Let’s say Anthony didn’t exist. In such a world, there can be no one complaining that her children matter “to me!” Instead, her children just exist as brute facts. How then can we ground their significance? Well, it seems the answer for people like Anthony would be to point to the children’s other family say “Those children matter to them!” We could continue this process almost endlessly. As we eliminate the children’s family, friends, etc. and literally make them just exist on their own, we find Anthony’s answer about allegedly objective morality supervenes on fewer and fewer alleged moral facts. Suddenly “Those children matter to themselves!” is the answer. But then what if we eliminate them? Do humans still have value? The whole time, Anthony has grounded the significance of her children and other humans in the beliefs, goals, and purposes of humans. But without humans, suddenly there is no significance. That’s what is meant by objective morality. If those children matter even without humans, then objective morality is the case. But Anthony has done nothing to make this the case; she’s merely complained that her children matter to her.

Now, some atheists–Anthony and Sam Harris included–seem to think they have answers to these questions. They seem to think that they can ground objective morality. We’ll turn to those next.

Suffering

One of the linchpins of humanists’ claims (like Anthony and Sam Harris) is suffering. The claim is that we can know what causes suffering, and that this, in turn, can lead us to discover what is wrong. We should not cause suffering.

But why not?

Most often the response I’ve received to this question is simply that because we do not wish to suffer, we should not wish to have others suffer or cause suffering for others. But why should that be the case? Why should I care about others’ suffering, on atheism? That’s exactly the question humanism must answer in order to show that objective morality can exist in conjunction with secularism. But I have yet to see a satisfactory answer to this question.

Anthony was presented with a similar question in the Q&A segment of her debate with William Lane Craig. One person asked (paraphrased), “Why shouldn’t I base morality as ‘whatever benefits me the most’?” Anthony responded simply by simply arguing essentially that it’s not right to seek pleasure at the expense of others, because they may also want pleasure.

But of course this is exactly the point! Why in the world should we think that that isn’t right!?

The bottom line is that, other than simply asserting as a brute fact that certain things are right and wrong, atheism provides absolutely no answer to the question of moral objectivity. People like Anthony try to smuggle it in by saying it’s objectively wrong to cause suffering [usually with some extra clauses], but then when asked why that is wrong, they either throw it back in the face of the one asking the question (i.e. “Well don’t you think it’s wrong?”) or just assert it as though it is obviously true.

And it is obviously true! But what is not so obvious is why it is obviously true, given atheism. We could have simply evolved herd morality which leads us to think it is obviously true, or perhaps we’re culturally conditioned by our close proximity to theists to think it is obviously true, etc. But there still is no reason that tells us why it is, in fact, true.

Moral Facts

Anthony (and Harris, and others with whom I’ve had personal interactions) centralize “moral facts” in their metaethical account. As a side note, what is meant by “moral fact” is a bit confusing but I don’t wish to argue against their position through semantics alone. They claim that we can figure out objective morals on the basis of moral facts. Sam Harris, for example, argues that there is a “continuum of such [moral] facts” and that “we know” we can “move along this continuum” and “We know, we know that there are right and wrong answers about how to move in this space [along the moral continuum]” (see video here).

Now it is all well and good to just talk about “facts” and make it sound all wonderful and carefully packaged, but Anthony and Harris specifically trip up when they get asked questions like, “How do we figure out what moral facts are?”

Anthony was asked “How do you determine what the objective moral facts are”, and responded by saying, “We do it by, um, testing our reactions to certain kinds of possibilities, um, thinking about the principles that those reactions might entail; testing those principles against new cases. Pretty much the way we find out about anything” (approximately 2 hours into the recorded debate).

One must just sit aghast when one hears a response like that. Really? That is the way we discover moral truths? And that is the way we “find out about anything”? Now I guess I can’t speak for Anthony herself, but when I’m trying to find out about something, I don’t test my reaction to possibilities and then try to figure out what my reaction “might entail.” That is radical subjectivism. Such a view is utterly devastating for not just morality but also science, history, and the like. If I were to try to conduct scientific inquiry in this manner, science would be some kind of hodgepodge of my “reactions” to various phenomenon. Unwittingly, perhaps, Anthony has grounded the ontology of her morality in the reactions of people. But this error isn’t restricted to Anthony. Harris also makes this confounding mistake. His basic argument in the talk linked above is simply, “Science can tell us what people think about things, so it can tell us about morality.” This is, of course patently absurd. Suppose I tried to test these humanists’ theories on groups of people by sticking them in a room and having them watch all kinds of things from murder to the rape of children to images of laughter and joy. Now suppose I randomly sifted my sample among the population of the world, but somehow, by pure chance, got a room full of child molesters. As I observe their reactions, I see they are quite joyful when they observe certain detestable images. Now, going by Anthony/Harris’ way to “find out about anything” and thinking about what these people’s reaction entails, I conclude that pedophilia is a great good. But then I get a room full of parents with young children, who react in horror at these same images. Then, as I reflect on their reactions, I discover that pedophilia is a great evil. And I repeat this process over and over. Eventually, I discover that the one group was an aberration, but it was a group nonetheless.

One must just sit aghast when one hears a response like that. Really? That is the way we discover moral truths? And that is the way we “find out about anything”? Now I guess I can’t speak for Anthony herself, but when I’m trying to find out about something, I don’t test my reaction to possibilities and then try to figure out what my reaction “might entail.” That is radical subjectivism. Such a view is utterly devastating for not just morality but also science, history, and the like. If I were to try to conduct scientific inquiry in this manner, science would be some kind of hodgepodge of my “reactions” to various phenomenon. Unwittingly, perhaps, Anthony has grounded the ontology of her morality in the reactions of people. But this error isn’t restricted to Anthony. Harris also makes this confounding mistake. His basic argument in the talk linked above is simply, “Science can tell us what people think about things, so it can tell us about morality.” This is, of course patently absurd. Suppose I tried to test these humanists’ theories on groups of people by sticking them in a room and having them watch all kinds of things from murder to the rape of children to images of laughter and joy. Now suppose I randomly sifted my sample among the population of the world, but somehow, by pure chance, got a room full of child molesters. As I observe their reactions, I see they are quite joyful when they observe certain detestable images. Now, going by Anthony/Harris’ way to “find out about anything” and thinking about what these people’s reaction entails, I conclude that pedophilia is a great good. But then I get a room full of parents with young children, who react in horror at these same images. Then, as I reflect on their reactions, I discover that pedophilia is a great evil. And I repeat this process over and over. Eventually, I discover that the one group was an aberration, but it was a group nonetheless.

What does this mean?

Quite simply, it means that both Harris and Anthony haven’t made any groundbreaking theory of ethics. Rather, they’ve just made a pseudo-humanistic utilitarianism. They ground moral ontology in our “reactions” to various moral situations. The only way for them to say something is morally wrong if people have different reactions is either to go with the majority (utilitarianism) or choose one side or the other, which essentially turns into a kind of Euthyphro dilemma against atheists. Either things are wrong because enough people think they’re wrong (in which case morality is arbitrary) or things are wrong because they simply are wrong, period (in which case the humanist has yet to provide an answer for moral ontology).

Conclusion

Given the discussion herein, one can see that those atheists, humanists, and/or secularists who desire to ground objective morality still have a lot of work to do. Louise Anthony’s best attempt to ground morality boils down into radical subjectivism. Sam Harris’ account fares no better. Those who are trying to ground objective morality within an atheistic universe will just have to keep searching. The solutions Anthony and Harris have attempted to offer are vacuous.

Image Source:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SecularHumanismLogo3DGoldCropped.png

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Announcing my new site: “Eclectic Theist”

I have many more interests than just philosophy of religion and Christian apologetics. I’ve been longing for an outlet for these interests for some time. Finally, I got down to business and made a new blog: “Eclectic Theist.”

On this new site, I’ll be writing about topics not normally discussed here on “Always Have a Reason.” For example, my first main entry is a reflection on science fiction. On this new site I’ll be discussing my other interests. Readers on here may be surprised at how random my reading is sometimes. In my undergraduate studies, I was a social studies major and I read extensively about Mesoamerican history. Did you know that!? Well now you do, and guess what? I’ll be writing about it again. I also love World War 2 history and have been reading more in that area in what exists of my free time. Of course, I’m also a huge fan of science fiction and fantasy, role-playing games, and more. All of these will be featured on this new site.

Will there be crossover? Probably. I’ve already thought of a few posts which can bring my outside interests on here and vice versa. For example, a series I’ve been contemplating for a while about science fiction and Christianity will see its launch on here in just a few short weeks. Other topics may crossover as well as they come up.

Does this mean I’ll write less here? Absolutely not. I have posts lined up for weeks now, and I continue to add to them. I’ll be maintaining my regular posts on here and using “Eclectic Theist” as an outlet for my other creative energy. Please, take the time to check out my introductory post to “Eclectic Theist” and browse the two new posts I have up. The site will be expanding quickly, so be sure to subscribe.

I’m looking forward to seeing many of you over there and talking about topics that interest us apart from philosophy of religion.

Finally, because I like pictures, I’ll share one that I just put up over on the new site: a picture of Orson Scott Card and myself.

Really Recommended Posts 01/14/2012

It’s been a while since I’ve posted one of these. The holiday season had me a bit too busy to explore other sites! Sorry all! But here’s a new slew of posts I really recommend for your reading!

It’s been a while since I’ve posted one of these. The holiday season had me a bit too busy to explore other sites! Sorry all! But here’s a new slew of posts I really recommend for your reading!

Did Jesus even exist?– the title is pretty self-explanatory. Rather than focusing on varied historical accounts, though, this post surveys several non-believers quotes on the topic.

Undesigned Scriptural Coincidences: The Ring of Truth– One of the old, forgotten arguments of historical apologetics is experiencing a major revival thanks in large part to the contributions of philosopher Tim McGrew. Christian Apologetics UK has this simply phenomenal post on the topic. Basically, the argument shows that without intending to do so, writers in the Bible omit and fill in each others’ details that they wouldn’t have seen as all that important. In doing so, however, they demonstrate the truth of the Biblical account. Check out this post!

Does the Bible teach that faith is opposed to logic and evidence?– Check out this post on the Biblical view of faith.

What if God were really bad?– Glenn Peoples is one of my favorite philosophers. He’s insightful, witty, and just plain interesting. In his latest podcast, he confronts Stephen Law’s “Evil God challenge” head on. Check it out!

William Lane Craig rebuts the “Flying Spaghetti Monster”– Self-explanatory. Check out Craig’s answer to a question about the FSM.

Nicolas Steno: bishop and scientist– I love posts that are mini-biographies of Christians who also did science. Check this one out, I bet you didn’t know about this guy!

Stephen Hawking: God Could not Create the Universe Because There Was No Time for Him to Do So– Jason Dulle provides an analysis of Hawking’s argument against creation. This is an excellent post and I highly recommend it.

Modal Realism, the Multiverse, and the Problem of Evil– Considerations of the multiverse with the problem of evil. Succinct and interesting!

The Moral Argument: Mistakes to Avoid and Practical Advice

The moral argument has experienced a resurgence of discussion and popularity of late. Some of this may be due to the increased popularity of apologetics. Philosophical discussions about metaethics also seem to have contributed to the discussions about the moral argument. Regardless, the argument, in its many and varied forms, has regained some of the spotlight in the arena of argumentation between theism and atheism. [See Glenn Peoples’ post on the topic for more historical background.]

The moral argument has experienced a resurgence of discussion and popularity of late. Some of this may be due to the increased popularity of apologetics. Philosophical discussions about metaethics also seem to have contributed to the discussions about the moral argument. Regardless, the argument, in its many and varied forms, has regained some of the spotlight in the arena of argumentation between theism and atheism. [See Glenn Peoples’ post on the topic for more historical background.]

That said, it is an unfortunate truth that many misunderstandings of the argument are perpetuated. Before turning to these, however, I’ll lay out a basic version of the argument:

P1: If there are objective moral values, then God exists.

P2: There are objective moral values.

Conclusion: Therefore, God exists.

It is not my purpose here to offer a comprehensive defense of the argument. Instead, I seek to lay out some objections to it along with some responses. I also hope to caution my fellow theists against making certain errors as they put the argument forward.

Objections

Objection 1: Objective moral values can’t exist, because there are possible worlds in which there are no agents.

The objection has been raised by comments on my site (see the comment from “SERIOUSLY?” here), but I’ve also heard it in person. Basically, the objection goes: Imagine a world in which all that existed was a rock. There would clearly be no morality in such a universe, which means that P2 must be false. Why? Because in order for there to be objective moral values, those values must be true in all possible worlds. But the world we just imagined has no morality, therefore there are no objective moral values!

The objection as outlined in italics above is just a more nuanced form of this type of argument. What is wrong with it? At the most basic level, the theist could object to the thought experiment. According to classical theism, God is a necessary being, so in every possible world, God exists. Thus, for any possible world, God exists. Thus, to say “imagine a world in which just a rock exists” begs the question against theism from the start.

But there is a more fundamental problem with this objection. Namely, the one making this objection has confused the existence of objective morals with their obtaining in a universe. In other words, it may be true that moral truths are never “activated” or never used as a judgment in a world in which only a rock exists, but that doesn’t mean such truths do not exist in that universe.

To see how this is true, consider a parallel situation. The statement “2+2=4” is a paradigm statement for a necessary truth. Whether in this world or in any other world, it will be the case that when we add two and two, we get four. Now consider again a world in which all that exists is a rock. In fact, take it back a step further and say that all that exists is the most basic particle possible–it is indivisible and as simple as physically possible. In this universe, just one thing exists. The truth, “2+2=4” therefore never will obtain in such a world. But does that mean “2+2=4” is false or doesn’t exist in this world? Absolutely not. The truth is a necessary truth, and so regardless of whether there are enough objects in existence to allow it to obtain does not effect its truth value.

Similarly, if objective moral values exist, then it does not matter whether or not they obtain. They are true in every possible world, regardless of whether or not there are agents.

Objection 2: Euthyphro Dilemma- If things are good because God commands them, ‘morality’ is arbitrary. If God commands things because they are good, the standard of good is outside of God. This undermines the moral argument because it calls into question P1.

Here my response to the objection would be more like a deflection. This objection only serves as an attack on divine command theory mixed with a view of God which is not like that of classical theism. Thus, there are two immediate responses the theist can offer.

First, the theist can ascribe to a metaethical theory other than divine command ethics. For example, one might adhere to a modified virtue theory or perhaps something like divine motivation theory. Further, one could integrate divine command ethics into a different metaethic in order to preserve the driving force of divine commands in theistic metaethics while removing the difficulties of basing one’s whole system upon commands. In this way, one could simply defeat the dilemma head-on, by showing there is a third option the theist can consistently embrace.