apologetics

Really Recommended Posts 9/6/13- Dystopia, Poetry, and Creationism (+more!)

Another look around the internet this week, as we investigate young earth creationism from a few angles, intelligent design, some dead guys, and dystopian fiction. Let me know what you think!

Another look around the internet this week, as we investigate young earth creationism from a few angles, intelligent design, some dead guys, and dystopian fiction. Let me know what you think!

Christian Virtues in Dystopian Fiction– Look, if you read my blog much you’ll know I am an absolute sucker for science fiction. One recurring theme in sci-fi is that of a dystopia: attempts to make a perfect world gone wrong. Most recently, The Hunger Games is a great example of the genre. In this post, Garret Johnson explores Christian Virtues found in this genre. It is a truly fascinating post, and I highly recommend you follow the blog to see more of the like.

Dead Guys, a poem– A very clever poem with a comic about the need to look at the works of the past in order to understand the present more fully. We stand on the shoulders of giants. I have written about the need to read more of the classic defenses of Christianity and theology, along with several ways to direct reading in my post, “On the Shoulders of Giants.”

A Horse is a Horse According to Answers in Genesis– An analysis of a recent attempt to present evidence for the young earth paradigm, this post looks at the genetic lineage of various species of horse. It is pretty awesome.

Stephen C. Meyer debates Michael Ruse about intelligent design and evolution on NPR– A “snarky” summary of a recent debate between Intelligent Design theorist Stephen Meyer and atheist Michael Ruse. Check out the review and listen to the debate.

Compromising Christians Don’t Like “Evolution vs. God” Film– I am “recommending” this post not because I endorse its contents, but because I think it shows how not to interact in “in-house” debates with other Christians. Ken Ham constantly uses the scare word “compromise” as a descriptor for other Christians. Compromise on what? Ham’s preferred interpretation of the text. It is a word he uses as a weapon time and again. As for the film itself, for some other perspectives (both positive and negative), check out my previous RRP.

**As always my linking to a post does not imply I endorse all or even part of that site**

Really Recommended Posts 8/30/13- Dinosaurs, Mumford and Sons, Design, and more!

Another search of the internet has turned up a number of excellent posts. I have found another diverse array of topics for you to browse at your leisure. This week, we’ll look at dinosaurs, Ray Comfort’s Evolution vs. God, cave diving, preterism, design, the economy, and Mumford and Sons!

Another search of the internet has turned up a number of excellent posts. I have found another diverse array of topics for you to browse at your leisure. This week, we’ll look at dinosaurs, Ray Comfort’s Evolution vs. God, cave diving, preterism, design, the economy, and Mumford and Sons!

Dinosaurs, Dragons and Ken Ham: The Literal Reality of Mythological Creatures– Often, the claim is made that legends about dragons sprang from humans living alongside dinosaurs. Young earth creationists cite this as evidence for their position. Here, the Natural Historian sheds some light on these claims in a well-researched post with plenty of pictures for those of us with short attention spans. I highly recommend following this blog as it remains an outlet for great analysis of young earth claims.

Evolution vs God– Another issue which has been making the rounds on apologetics/Christian sites has been the recent video by Ray Comfort, “Evolution vs God.” The video is available to watch for free on youtube. Feel free to check it out yourself (you can find a link to it here). My good friend over at No Apologies Allowed seems to endorse it to a limited extent (see his comment on this post), and his comments have touched off a great discussion: [DVD] Evolution vs. God. On the other hand, the Christian think-tank Reasons to Believe has offered their own brief video review (the link will stat playing instantly) of the movie which has a very different perspective. What are your thoughts?

Some Questions Concerning my Preterism– I am not a preterist, but I appreciate well thought out positions and the insights they provide into their positions. Here, Nick Peters shares a number of question-and-answers related to his preterist views. Preterism is the view that the majority of the prophecies found in Revelation and the like have been fulfilled, usually in the destruction of the Temple in AD 70.

The theory of intelligent design (Video)- As one friend sharing this video put it: “A video on MSN featuring Michael Behe narrated by Morgan Freeman? What world did I wake up in?” My thoughts exactly. This video is a very basic exposition of the theory of intelligent design. Check it out.

Cave Diving and Apologetics– I like caves, though I have never done cave diving and almost certainly never will. I found this post to be fairly helpful in regards to drawing out some of the dangers of apologetics and going everywhere at once. I wasn’t terribly appreciative of the explicit appeal to defense of Catholic dogma, but apart from that the post is pretty solid.

Mumford & Sons: Five Songs With All Sorts of Christian Undertones– A really excellent look into several Mumford & Sons songs. I admit I’m not a big fan of the style of music, but I found this post fascinating nonetheless. Check it out.

What happened to the economy after Democrats won the House and Senate in 2007?– People who know me personally realize that I am a complete mishmash of political views. I frankly despise both major political parties because I think they are both ridiculously partisan and do little correctly. That said, I found this post to be a pretty interesting look at the economics of policy. Let me know what you think.

Inerrancy and Presuppositional Apologetics: A different approach to defending the Bible

Scripture is inerrant because the personal word of God cannot be anything other than true. -John Frame (The Doctrine of the Word of God

, 176 cited below)

One of the most difficult issues facing evangelical Christian apologists is the doctrine of inerrancy. I’m not trying to suggest the doctrine is itself problematic. Indeed, I have defended the doctrine in writing on more than one occasion. Instead, I am saying that defending this doctrine in an apologetics-related discussion is difficult. Here, I will explore one way that I think should be used more frequently when discussing the doctrine.

What is the problem?

There are any number of attacks on inerrancy and Biblical authority, generally speaking. Very often, when I discuss the Bible with others in a discussion over worldviews, I find that the challenge which is most frequently leveled against the notion of inerrancy is a series of alleged contradictions. The second most common objection is some sort of textual criticism which allegedly shows that the Bible could not be without error in its autographs. A third common argument against inerrancy is to quote specific verses and express utter incredulity at their contents.

Of course, it doesn’t help that the definition of inerrancy is often misunderstood. For simplicity’s sake, I will here operate under the definition that “The Bible, in all it teaches, is without error.” I have already written on some misconceptions about the definition of inerrancy, and readers looking for more clarification may wish to read that post.

How do we address the problem?

Most frequently, the way I have seen apologists engage with these challenges is through a series of arguments. First, they’ll argue for the general reliability of the Bible by pointing out the numerous places in which it lines up with archaeological or historical information we have. Second, they’ll argue that these historical reports given in the Bible cannot be divorced from the miraculous content contained therein. Given the accuracy with which these writers reported historical events, what basis is there to deny the miraculous events they also report?

Other apologists may establish inerrancy by rebutting arguments which are leveled against the doctrine. That is, if one puts forth an argument against inerrancy by pointing out alleged contradictions, these apologists seek to rebut those contradictions. Thus, once every single alleged error has been addressed, this approach concludes the Bible is inerrant.

Now, I’m not suggesting that either of these methods are wrong. Instead, I’m saying there is another way to approach the defense of the Bible.

A Presuppositional Defense of Inerrancy

Suppose God exists. Suppose further that this God which exists is indeed the God of classical Christian theism. Now, supposing that this is the case, what basis is there for arguing that the Bible is full of errors? For, given that the God of Christianity exists, it seems to be fairly obvious that such a God is not only capable of but would have the motivation to preserve His Word as reported in the Bible.

Or, consider the first step-by-step argument for inerrancy given in the section above, where one would present archaeological, philosophical, historical, etc. evidence point-by-point to make a case for miracles. Could it not be the case that the only reason for rejecting the miraculous reports as wholly inaccurate fictions while simultaneously acknowledging the careful historical accuracy of the authors is simply due to a worldview which cannot allow for the miraculous at the outset?

What’s the Point?

At this point one might be thinking, So what? Who cares?

Well, to answer this head on: my point is that one’s overall worldview is almost certainly going to determine how one views inerrancy. The point may seem obvious, but I think it is worth making very explicit. If we already hold to a Christian worldview broadly, then alleged contradictions in the Bible seem to be much less likely–after all, God, who cannot lie (Numbers 23:19), has given us this text as His Word. Here it is worth affirming again what John Frame said above: the Bible is inerrant because it is of God, who is true.

Thus, if one is to get just one takeaway from this entire post, my hope would be that it is this: ultimately the issue of Biblical inerrancy does not stand or fall on whether can rebut or explain individual alleged errors in the Bible–it stands or falls on one’s worldview.

One final objection may be noted: Some Christians do not believe in inerrancy, so it seems to go beyond an issue of worldview after all. Well yes, that is true. I’m not saying a defense of inerrancy is utterly reducible down to whether or not one is a Christian or not–as I said, I think evidential arguments are very powerful in their own right. I am saying that inerrancy is impossible given the prior probabilities assigned by non-Christian worldviews and altogether plausible (not certain) given Christian worldview assumptions.

A Positive Case for Inerrancy

Too often, defense of inerrancy take the via negativa–it proceeds simply by refuting objections to the doctrine. Here, my goal is to present, in brief, a positive argument for inerrancy. The argument I am proposing here looks something like this (and I admit readily that I have left out a number of steps):

1) Granting that a personal God exists, it seems likely that such a deity would want to interact with sentient beings

2) such a deity would be capable of communicating with creation

3) such a deity would be capable of preserving that communication without error

Therefore, given the desire and capability of giving a communication to people without error, it becomes vastly more plausible, if not altogether certain, that the Bible is inerrant. Of course, if God does not exist–if we deny that there is a person deity–then it seems altogether impossible that an inerrant text could be produced on anything, let alone a faith system.

I consider this a positive argument because it proceeds from principles which can be established (or denied) as opposed to a simple assertion. It is not a matter of just presupposing inerrancy and challenging anyone who would take it on; instead it is a matter of arguing that God exists, desires communication with His people, and has brought about this communication without error. Although each premise needs to be expanded and defended on its on right, I ultimately think that each is true or at least more plausible than its denial. Christians who deny inerrancy must, I think, interact with an argument similar to this one. Their denial of inerrancy seems to entail a denial of one of these premises. I would contend that such a denial would be inconsistent within the Christian worldview.

Note that this argument turns on the issue of whether or not God exists. That is, for this argument to be carried, one must first turn to the question of whether God exists. I would note this is intentional: I do think that inerrancy is ultimately an issue which will be dependent upon and perhaps even derivative of one’s view of God.

Other Books

One counter-argument which inevitably comes up in conversations about an argument like this is that of “other books.” That is, could not the Mormon and the Muslim (among others) also make a similar case.

The short answer: Yes, they could.

Here is where I would turn to the evidence for each individual book. Granting a common ground that these claimed revelations–the Bible, the Book of Mormon, the Qu’ran, etc.–are each purported to be inerrant and that their inerrancy is more probable on a theistic view, which best matches reality? In other words, I would turn here to investigate the claims found within each book in order to see if they match with what we can discern from the world.

The argument I am making here is not intended to be a one step argument for Christian theism. Instead, it is an argument about the possibility of an inerrant work.

Appendix 1: Poythress and Inerrancy

Appendix 1: Poythress and Inerrancy

Vern Poythress provides an example of how this approach works. In his work, Inerrancy and Worldview (my review of this work can be found here), he continually focuses on how worldviews color one’s approach to challenges presented against inerrancy such as historical criticism, certain sociological theories, and philosophy of language. One example can be found in his discussion of historical criticism:

The difference between the two interpretations of the principle [of criticism] goes back to a difference in worldview. Does God govern the universe, including its history, or do impersonal laws govern it? If we assume the latter, it should not be surprising that the resulting principle undermines the Bible… It undermines the Bible because it assumes at the beginning that the God of the Bible does not exist. (Poythress, Inerrancy and Worldview

, 53, cited below)

Yet it is important to see that my approach here is different from that of Poythress. His approach seems to be largely negative. That is, he utilizes presuppositionalism in order to counter various challenges to the Bible. When a challenge is brought up to inerrancy, he argues that it of course stems from an issue of worldview. Although this is similar to my approach, Poythress never makes a positive argument for inerrancy, which I consider to be a vital part of the overall defense of the doctrine.

Appendix 2: Standard Presuppositionalism and Inerrancy

I would like to note that I am not attempting to claim that my defense of inerrancy here is the standard presuppositional approach. The standard presuppositional approach is much simpler: the apologist simply assumes the absolute truth and authority of God’s word as the starting point for all knowledge.

It should not surprise readers that, given this approach, most (if not all) presuppositionalists embrace the via negativa for defense of inerrancy. That is, the standard presuppositional defense of the Bible usually is reducible to merely pointing out how the attacks on Scripture stem largely from one’s worldview, not from the facts.

Thus, one of the foremost presuppositional apologists to have lived, Greg Bahnsen, writes:

[I]f the believer and unbeliever have different starting points [that is, different presuppositions from which all authority comes for the realm of knowledge] how can apologetic debate ever be resolved? [In answer to this,] the Christian carries his argument beyond “the facts…” to the level of self-evidencing presuppositions–the ultimate assumptions which select and interpret the facts. (Bahnsen, Always Ready, 72 cited below).

It should be clear that this standard presuppositional defense is therefore very different from what I have offered here. The standard presuppositional defense simply reduces the debate to “starting points” and attempts to show contradictions in other “starting points” in method, exposition, or the like. My defense has noted the vast importance of worldviews in a denial of inerrancy, but has also offered a positive defense of inerrancy. Yes, this defense turns on whether God exists, but that can hardly be seen as a defect or circularity in the argument.

Links

Like this page on Facebook: J.W. Wartick – “Always Have a Reason.” I often ask questions for readers and give links related to interests on this site.

The Presuppositional Apologetic of Cornelius Van Til– I explore the presuppositional method of apologetics through a case study of the man who may fairly be called its founder, Cornelius Van Til.

Debate Review: Greg Bahnsen vs. Gordon Stein– I review a debate between a prominent presuppositional apologist, the late Greg Bahnsen, and a leading atheist, Gordon Stein. It is worth reading/listening to because the debate really brings out the distinctiveness of the presuppositional apologetic.

Sources

Greg Bahnsen, Always Ready (Nacogdoches, TX: Covenant Media Press, 1996).

John Frame The Doctrine of the Word of God (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2010).

Vern Sheridan Poythress, Inerrancy and Worldview (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Really Recommended Posts: 6/7/13- Mormonism, The Ice Age, and more!

Dear Reader, it is now that time to once more share with you my own wanderings across the internet. I have brought to you a random mix of posts which interested me. Given that you still choose to read my site, you probably have some random interests which match my own. Thus, I’ve done your work for you. For free. No problem. Just check out the posts! This week, we have the Ice Age and Creationism, Mormonism, Papal Infallibility,Constantine, the need for apologetics, and an archaeological mystery for you to solve. Leave a comment. Let me know what you liked. Have a post you think I need to read? Well, pass it along!

Dear Reader, it is now that time to once more share with you my own wanderings across the internet. I have brought to you a random mix of posts which interested me. Given that you still choose to read my site, you probably have some random interests which match my own. Thus, I’ve done your work for you. For free. No problem. Just check out the posts! This week, we have the Ice Age and Creationism, Mormonism, Papal Infallibility,Constantine, the need for apologetics, and an archaeological mystery for you to solve. Leave a comment. Let me know what you liked. Have a post you think I need to read? Well, pass it along!

Mormonism and Christianity: which one is supported by the evidence?– Do you like evidence to go along with your beliefs? I sure do. Wintery Knight investigates the claims of Mormonism and Christianity to discern which one has better evidential support. Read this… you will not be disappointed.

The Pleistocene is Not in the Bible– “Pleistocene” is basically a fancy name for “Ice Age.” Check out this post, which investigates one major young earth creationist claim about the Ice Age and the Bible.

Before “Infallibility” Was a Twinkling in a Pope’s Eye– I found this post very interesting because I have a major love for historical theology and the interplay between history and theology. The author explores the historical development of Papal Infallibility.

It Should Never have Come to That Point– I found this a powerful call for churches to engage in apologetics. I think apologetics is a vital educational tool and anyone who says we don’t need it needs to think again. Check out my own post as a call to apologetics.

Was Constantine a Christian or Pagan?– Constantine has a pretty bad reputation in many circles. Here, Max Andrews addresses some of the more pressing questions about Constantine’s life. I think that in places the case is overstated, but he brings to light many interesting issues to discuss. Look forward to a post from me on Constantine sometime in the (fairly distant) future.

Massive submerged structure stumps Israeli archaeologists– I found this an interesting little piece of archaeological mystery. What was this thing? I’ll be taking your submissions in the comments here.

As always, note that my linking to a post does not entail my endorsement of all of its content.

William Paley (1743-1805) – Historical Apologist Spotlight

William Paley (1743-1805) is a name which echoes through history. His Natural Theology

William Paley (1743-1805) is a name which echoes through history. His Natural Theology continues to have a profound and lasting impact on the argument from biological design. His Evidences of Christianity

challenges readers on a historical and exegetical level with arguments for the faith. Unfortunately, too few have thoughtfully interacted with his arguments. Here, we will first look at Paley’s views and life. Then, we will examine his major works and arguments. We will discover there is much to learn from this intellectual giant. Note that this post is necessarily brief, and that readers are greatly encouraged to go to the primary sources found below.

Brief Biographical Note*

Paley went to school at Christ’s College and Cambridge. At the latter, he was awarded multiple times for his scholarship. He eventually became the Senior Dean at Christ’s College and was awarded a Doctorate of Divinity from Cambridge. Bishop Barrington of Durham granted him the rectory of Bishop Wearmouth. His life was strewn with accomplishments.

He was a utilitarian with deep Christian convictions. Throughout his life, he remained controversial. His utilitarianism was condemned, as was his critique of the often extreme defenses of property ownership. His anti-slavery was unpopular alongside his support of the American Colonies in the Revolutionary War.

The powerful nature of Paley’s works is revealed in the fact that his major work on utilitarianism, The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy, became mandatory reading at Cambridge. His Natural Theology continues to be discussed in courses on philosophy of religion. The man was acclaimed by some within the church, who praised his defense of the faith despite others’ objections to his metaethical views.

His contributions to Christian apologetics are the focus of this piece, and we shall turn to them now.

Natural Theology

Paley’s most famous work nowadays is undoubtedly Natural Theology. In this work, he makes his well-known case for the design argument. He utilizes the analogy of a watch. If one finds a watch on a beach, one knows instantly that someone made the watch. Paley applied this same notion to life; one sees the sheer complexity and life and can infer that it, like the watch, was designed.

Many have dismissed Paley’s work here, noting that at points he relies on scientific explanations which have been discredited, while at others his examples have been explained. Yet the genius of his work is found in broader principles, which moderns should note. First, he argued that simply never having observed design in action on a biological level does not preclude any possibility of arguing for that same design (Natural Theology, 8, cited below). Second, evidence of things “going wrong” within a design does not invalidate the design of an object in and of itself. Third, higher level natural laws which may lead to order does not explain away the order itself. Fourth, when something appears to be designed, the burden of proof is upon those who assert an object is not designed.

These points seem to me to hold true to this day. I am sure none of them are uncontroversial, but Paley places his defense of this points squarely within his analysis of those artifacts which he considers to be designed (i.e. the eye and ear). A full treatment of these points thus must turn to his own arguments, but for now I would provide the following brief defenses. Regarding the first, this point seems obvious. If I have never seen someone construct a car, that does not in any way mean that I cannot conclude that someone had to have made it. The second point should be well taken within the context of the debate between Intelligent Design and Darwinian forms of evolution. The point is that simply pointing out a flaw in a design does not mean an entire object is undesigned. The third item seems correct because if something exhibits order, and that order is shown to be based around an ordering principle, the very order in and of itself has not been explained; instead, it is only the mechanism for generating that order which is observed. Finally, the fourth point is likely to be the most controversial–after all, appearances may deceive. Yet it does seem to be the case that if, a priori, something appears designed, then to conclude that something is not designed one must have defeating evidence for this appearance.

A View of the Evidences of Christianity

Paley’s Evidences (commonly known as “Evidences of Christianity”) became almost instantly famous. The work generated a number of summaries and expositions by other authors who were delighted with its style and the arguments contained therein. It is easy to see why, once one has begun a read through this apologetic treatise. Paley presents a number of arguments in favor of the Christian worldview. These evidences are largely historical in nature and include the suffering of those who spread Christianity as evidence for its truth, extrabiblical evidence for the truth of the Gospels, the authenticity of our Gospel accounts due to the early practices and beliefs of Christians, undesigned coincidences, and many more. Paley also provides a dismantling of David Hume’s argument against miracles.

It seems to me that any and all of these arguments retain the force they had in Paley’s own day. Consider the argument from the suffering of Christians. Well of course those of other faiths are willing to even die for that which they believe is true. But Paley rightly pointed out a huge difference between those of other faiths dying for their beliefs and the early eyewitnesses of the events surrounding Christ dying for their own beliefs. Namely, these people would know for certain whether that which they believed were true. That is, they either saw the resurrected Christ or they did not. If they did not, then explaining their willingness to die for this profession of faith becomes extremely difficult. However, if they did actually see that which they declared, their willingness to suffer unto death for this belief makes perfect sense. Many miss this important distinction even to this day. The rest of Paley’s arguments found in the Evidences is filled with insights similar to this.

Horae Paulinae

An argument which has largely been neglected within modern apologetic circles is that of “undesigned coincidences.” I have made an exposition of this argument already, and it should be noted that the best places to discover it are in the realm of historical apologetics. William Paley dedicated this work, Horae Paulinae, to discovering undesigned coincidences within the Pauline corpus alongside Paul’s history as written in Acts.

Now, the argument from undesigned coincidences takes quite a bit of work to properly outline. It is, in essence, a matter of looking through the Scriptures and finding how incidental details in one account fill in the blanks of another account. However, this description is so brief as to be simplistic. Paley himself acknowledged a number of the difficulties with describing undesigned coincidences in this way. Regarding the Pauline corpus, for example, it could be that someone invented letters from Paul but based them upon his history found in Acts. But the argument itself takes this into account and generally serves as a defeater for this notion by sheer weight of evidence. That is, the more coincidences are found, the more credulity is stretched if one wishes to assert forgery.

Paley buries the objections to undesigned coincidences in this fashion throughout the Horae Paulinae. The sheer volume of coincidences he finds, and the way they seem so clearly to be incidental, serves to dispel doubts about their genuine nature.

Other Works

Here, we have surveyed Paley’s major works, but he was a prolific writer who published sermons and of course his (in)famous work on utlitarian ethics. The preeminence of Paley as a scholar and writer is unquestionable. It is time we acknowledge how much we have to learn from those who have come before us.

Conclusion

We have seen the diverse array of arguments which Paley offered in favor of Christianity. These ranged from biological design arguments to undesigned coincidences to historical arguments in favor of the Gospels. Paley was a masterful writer whose arguments continue to influence apologists and draw ire from atheists to this day. Although the arguments have not been unscathed, I have offered a few reasons to reconsider some which have long been dismissed or forgotten. Paley’s influence endures.

I would like to dedicate this post to Tim McGrew, who introduced me to the vast field of historical apologetics. Without his bubbling delight and enthusiasm in the field, I would never have known much–if anything–about people like Paley. It is my hope and prayer that you may also be persuaded to pursue historical apologetists/apologetics. Be sure to check the links for some good starting places.

Be sure to check out the links at the end of this post as well as the resources from Paley.

Links

Like this page on Facebook: J.W. Wartick – “Always Have a Reason.” I often ask questions for readers and give links related to interests on this site.

Library of Historical Apologetics– Here is where I got started, with Tim McGrew’s phenomenal collection of works. In particular, the “annotated bibliography” will set you up with some fine works. The site features a “spotlight” on the main page for various fantastic reads. Browse and download at will. Also check out their Facebook page.

On the Shoulders of Giants: Rediscovering the lost defenses of Christianity– I provide a number of links as well as an annotated list of historical apologetics works which are great jumping off points for learning more about the vast array of arguments which have largely been forgotten within the realm of apologetic argument. I consider this one of the most important posts on this site.

Forgotten Arguments for Christianity: Undesigned Coincidences- The argument stated– Here I outline the argument from undesigned coincidences and explain how it can be used within apologetics.

Sources

William Paley, Evidences of Christianity (this is a free link for the item on Kindle, note that it is also available for purchase in a hard copy). Also see here for a few links to PDF versions of the book.

—-, Natural Theology (Oxford World’s Classics) – This link is for the Kindle edition which I used for this post. I highly recommend this specific edition due to the helpful introduction and other information included in the text. It can be found for free here.

—-, Horae Paulinae – this link is to the kindle version. It is also available for free here.

*I am indebted to the discussion of Paley’s life found in the introduction of the Oxford Classic’s edition of Paley’s Natural Theology, which I have cited above.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

If a Good God Exists: Presuppositional Apologetics and the problem of evil

It is clear that all things are ordered according to the perfect will of the Lord. If the Lord’s reasons for some state of affairs are inscrutable, does that mean that they are unjust? (Augustine, City of God

Book V, Chapter 2).

The problem of evil is the most pervasive argument used against Christianity. It also causes the most doubts among Christians. I know I can attest to crying out to God over the untold atrocities which continue to happen. Yet very often, I think, we are asking the wrong question. Here, I’ll explore the ways the problem of evil is presented. Then, I’ll offer what I think is a unique answer: the presuppositional response to the problem of evil. Finally, we’ll evaluate this response.

Two Ways to Present the Problem of Evil

The problem of evil is posed in a number of ways, but here I’ll outline two varieties.

The Classical/Logical Problem of Evil

God is said to be all powerful and all good, yet evil exists. Thus, it seems that either God does not want to prevent evil (in which case God is not all good) or God is incapable of preventing evil (and is thus not all powerful).

The Evidential Problem of Evil

Evil on its own may not prove that God does not exist (the logical/classical problem of evil), but it seems that surely the amount of evil should be less than what we observe. Surely, God is capable of reducing the amount of suffering by just one less child being beaten, or by one less tsunami killing hundreds. The very pervasiveness of evil makes it clear that no good God exists.

The Presuppositional Response to the Problem of Evil

One of the insights that we can gain from presuppositional apologetics is that it forces us to look at our preconceived notions about reality and how the impact our answers to questions and even the questions we choose to ask. The way that the problems of evil are outlined provides a prime example for how presuppositional approach to apologetics provides unique answers.

The presuppositional answer to these problems of evil is simple: If a good God exists, then these are not problems at all.

Of course, this seems overly simplified, and it is. But what the presuppositionalist is emphasizing is that the only way to make the two problems above make sense is to come from a kind of neutral or negative starting presupposition. The only way to say to construct the dilemma in the classical/logical problem of evil is to assume that there is not an all-powerful and all-good God to begin with. For, if an omnibenevolent, omnipotent being exists, then to say that God does not want to prevent evil seems false; while to say that God is incapable of preventing evil is also false. Thus, there would have to be a third option: perhaps God reasons for allowing evil are inscrutable; perhaps the free will defense succeeds; etc. Only if one assumes that there is no God can one make sense of the logical problem of evil to begin with.

The evidential problem of evil suffers an even worse conundrum given its presuppositions. For it once more assumes that God should do more to prevent evil, and so because God does not do more, God must not exist or must not care about evil. But who is to say that God should do more to prevent evil? Who is in a position to judge the overall evil in the world and say that there should be less? Furthermore, even assuming it were possible for there to be less evil, who knows the whole breadth of possible purposes God might have to allow for suffering and evil? The presuppositionalist agrees with the words of God in Job:

Who has a claim against me that I must pay?

Everything under heaven belongs to me. Job 41:11

The answer must come with humility: no one has such a claim. There is none who can claim that God owes them one thing. Yet this is not all an appeal to God’s sovereignty. Instead, it is an appeal to God’s goodness.

The late Greg Bahnsen, a defender of presuppositional apologetics, presents the presuppositional approach to the problem of evil in his work, Always Ready:

If the Christian presupposes that God is perfectly and completely good… then he is committed to evaluating everything within his experience in light of that presupposition. Accordingly, when the Christian observes evil events or things in the world, he can and should retain consistency with his presupposition about God’s goodness by now inferring that God has a morally good reason for the evil that exists. (171-172)

Thus, the strength that one assigns to the problem of evil ultimately depends quite a bit upon one’s presuppositions. If you believe you have good reason for thinking that God exists, then the problem of evil seems much less powerful than if you believe there is no good reason for thinking God exists.

Yeah… and?

Okay, so what’s the point? It may be that what we bring to the table does indeed alter our view of the problem of evil. Does that mean we are at a complete impasse? I think that this is where evidences come in, even on the presuppositional view. If all we have are presuppositions, then we are indeed stuck. But we must look at evidences to see whose presuppositions match reality. And, what we have done by centering the discussion of the problem of evil around presuppositions is to set it to the side. Surely the atheist would not suggest the Christian must abandon their presuppositions? It seems like a more rational perspective to look at the evidences. The presuppositionalist holds that when it comes to evil, it is really just a matter of presuppositions. If a Good God exists, we can trust God.

Links

The Presuppositional Apologetic of Cornelius Van Til– I explore the presuppositional method of apologetics through a case study of the man who may fairly be called its founder, Cornelius Van Til.

Debate Review: Greg Bahnsen vs. Gordon Stein– I review a debate between a prominent presuppositional apologist, the late Greg Bahnsen, and a leading atheist, Gordon Stein. It is worth reading/listening to because the debate really brings out the distinctiveness of the presuppositional apologetic.

I have explored this type of argument about the problem of evil before. See my post, What if? The “Job Answer” to the problem of evil.

I review Greg Bahnsen’s Always Ready.

Image credit: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Las_Conchas_Fire.jpg

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

“How Much Evidence to Justify Religious Conversion?” – John Warwick Montgomery on Conversion

I had the opportunity to hear John Warwick Montgomery speak at the Evangelical Theological/Philosophical Conference in 2012. He was one of the most engaging speakers I have ever had the pleasure of listening to. Here, we’ll look at his presentation alongside the journal article that he discussed. The topic was “How Much Evidence to Justify Religious Conversion?”*

I had the opportunity to hear John Warwick Montgomery speak at the Evangelical Theological/Philosophical Conference in 2012. He was one of the most engaging speakers I have ever had the pleasure of listening to. Here, we’ll look at his presentation alongside the journal article that he discussed. The topic was “How Much Evidence to Justify Religious Conversion?”*

Conversion and Evidence

Montgomery began by discussing the possibility of a position which had so much evidence that it becomes difficult to not believe it. Despite this, people do not hold that position. The reason, he argued, is because reasons other than evidence play into one’s conversion. Moreover, we live in a pluralistic age, which means that there are a vast array of options available to people looking for a worldview. This pluralism necessitates a drop in conversion rates because there are more worldviews presenting their evidence to each individual. Thus, it is important to look into the issue of the burden of proof alongside the issue of the standard of proof.

Burden and Standard of Proof

Here, Montgomery turned to his experience in law to explore the notion. Simply put, the burden of proof can also be seen as the burden of persuasion . Montgomery noted that the prosecutor does not always carry the burden of proof because the defendant often provides a positive defense, and so has their own burden of proof. For example, if someone says “I could not have done x because I was doing y at the same time at location z” then they have made a positive claim which itself requires a burden of proof. Or, as Montgomery put it, “The person who wants to make a case has the burden of proof.”

But it is important to note that the burden of proof is not the same thing as a standard of proof. When people object to Christianity based upon a supposed lack of proof, they are not addressing the burden of proof but rather the standard. Montgomery acknowledged that Christianity must assume the burden of proof but makes several points related to the standard of proof.

First, proof “depends on probability–not on absolute certainty or on mere possibility” (Montgomery, 452, cited below). He appealed to the “Federal Rules of Evidence” to make this clear. The key is to note that probability ,not absolute certainty, is at stake. Why? Epistemologically speaking, absolute certainty can only be set out in formal logic or mathematics. It is unjustifiable to require absolute certainty for every fact. “Where matters of fact are concerned–as in legal disputes, but also in the religious assertions of historic Christianity–claims can be vindicated only by way of evidential probability” (Ibid).

Second, and more importantly for the current discussion, there are differing standards of proof. The legal system is again a model for this notion. In criminal trials, there is a higher standard of proof than for civil matters. The criminal standard is beyond reasonable doubt, while the civil standard is “preponderence of evidence.” Montgomery argued that religious conversion should be seen as bearing a standard of proof “beyond a reasonable doubt” (453).

Third, competing religious claims must each assume their own burden of proof. They cannot simply say “prove my religious claim false.” One must meet the standard of proof in order to have legitimate entry into the competition between worldviews.

Extraordinary Claims Need Extraordinary Evidence?

Often, the claim is made that religious claims, because they are extraordinary, need extraordinary evidence. I have written on this exact topic at length elsewhere, but here will focus on Montgomery’s argument. He argued “The notion that the ‘subject matter’ should be allowed to cause a relaxation or an augmentation of the standard of proof is a very dangerous idea…. No one would rationally agree to a sliding evidence scale dependent on the monetary sum involved [in a crime]–nor should such a scale be created… The application to religious arguments based on the factuality of historical events should be obvious. Of course, the resurrection of Christ is of immensely more significance than Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon, but the standards required to show that the one occurred are no different from those employed in establishing the other” (Ibid, 455-456).

The notion that the import of a claim makes a sliding scale of evidence is made to be absurd because historical events have more importance across cultures and so would, on such a view, be radically different in their acceptable standards of proof.

The Existential Factor

Finally, Montgomery focused on the existential side of conversion. Here, he offered what he admitted as a somewhat crude argument which was derived from Pascal’s wager. Assuming that the standard of proof is met for a religious system, one still must deal with the existential factors of conversion. Thus, Montgomery argued, one’s commitment to a truth claim should be weighed by the benefits divided by the entrance requirements: C=B/E.

Because the entrance requirements for Christianity are extremely low, and its benefits infinite, one should, assuming the standard of proof has been met, be highly committed to Christianity. Montgomery noted that some may argue the entrance requirements are very high (i.e. setting aside adulterous relationships). Against this, Montgomery argued that the benefits vastly outweigh the finite bliss one feels by such sinful actions.

Applications

The subtlety of Montgomery’s argument should not be missed. It has application in a number of areas. First, Montgomery is as thoroughgoing an evidentialist as they come. His argument about the standard of proof being probabilistic is unlikely to gain much credence among those who favor a presuppositional approach to apologetics.

Yet it seems to me that Montgomery’s argument in this regard is correct. We must take into account the evidence when we are looking at various religious claims, and also acknowledge the existential factors which play into conversion.

Montgomery’s argument does much to clarify the issue for apologists in general. Our task is to clear barriers and present convincing evidence to those who argue that Christianity has not met the standard of proof. But our task does not end with that; we must also present the existential challenge of Christianity to those who believe the standard of proof has been met. This includes the preaching of the Gospel.

Montgomery was also careful not to discount the Holy Spirit in religious conversion. He made it clear that he was speaking to the notion of conversion in the abstract. People must be renewed by the Holy Spirit; yet that renewal may come through evidence and standard of proof.

It seems to me that Montgomery’s arguments were insightful and sound. He presented an excellent way to look at religious claims and evaluate them in light of evidence, while also taking existential factors into account.

Links

Like this page on Facebook: J.W. Wartick – “Always Have a Reason”

Montgomery’s use of evidence in law to look at religious truth claims reminds me very much of J. Warner Wallace’s Cold Case Christianity. Check out my review of that fantastic book.

Extraordinary Claims need… what, exactly?– I argue that the claim that religious claims need extraordinary evidence is mistaken.

I have written about numerous other talks at the EPS Conference on an array of topics. Check them out:

Gregg Davidson vs. Andrew Snelling on the Age of the Earth– I write about a debate I attended on the age of the earth.

Caring for Creation: A dialogue among evangelicals– I discuss a lecture and panel discussion on caring for the environment.

Genetics and Bioethics: Enhancement or Therapy?– Here, I outline a fascinating talk I attended about gene enhancement and gene therapy.

You can read my overview of every single talk I attended: My Trip to the Evangelical Philosophical/Theological Society Conference 2012.

Sources

*Unless otherwise noted, the information herein was discussed in John Warwick Montgomery’s EPS 2012 Conference talk entitled “How Much Evidence to Justify Religious Conversion? Some Thoughts on Burden and Standard of Proof vis-a-vis Christian Commitment”

John Warwick Montgomery, “How Much Evidence to Justify Religious Conversion?” in Philosophia Christi 13, #1 2011, 449-460.

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

Book Review: “Inerrancy and Worldview” by Vern Sheridan Poythress

Vern Sheridan Poythress approaches the defense of the truth of the Bible in a unique way in his recently-released duo of books, Inerrancy and Worldview

Vern Sheridan Poythress approaches the defense of the truth of the Bible in a unique way in his recently-released duo of books, Inerrancy and Worldview and Inerrancy and the Gospels

. In these works, he has applied the presuppositional approach to apologetics to the doctrine of inerrancy. Here, we’ll explore the former and analyze Poythress’ approach to the defense of Biblical authority.

Overview

Poythress has set Inerrancy and Worldview out not so much as a treatise presenting a broad-based presuppositional approach to defending inerrancy, but rather the book is laid out in stages with sections focusing on various challenges which are raised against the Bible. Each stage ends with a focus on worldview and how one’s worldview shapes one’s perception of the challenge to the Bible.

That is the central thesis of the book: our preconceived notions shape how we will view the Bible. Poythress writes:

Part of the challenge in searching for the truth is that we all do so against the background of assumptions about truth. (21)

Thus, it is critical to recognize that one’s presuppositions will in some ways guide how they view the Bible.

Poythress then introduces the materialistic worldview as the primary presupposition for the Western world which sets itself up against a Biblical worldview. The essential point here is that the world is a very different place if primary causes are personal or impersonal.

From here, Poythress dives into the various challenges which are set up against the Bible. First, he looks at modern science. The major challenges here are the Genesis account of creation, which he argues is explained by God making a “mature creation” where the world appears aged (41) and other alleged scientific discrepancies, which he argues are due to God’s condescending to use human expressions to explain the concepts in the Bible (38-39).

What of historical criticism? Again, worldview is at the center. If God exists, then history inevitably leads where God wills it. If, however, one assumes the Bible is merely human, then it is unsurprising to see the conclusions which historical critics allege about the text.

Challenges from religious language are dealt with in the same fashion. On a theistic worldview, God is present “everywhere” including in “the structures of language that he gives us.” Thus, we should expect language to refer to God in meaningful ways (101). Only if one assumes this is false at the outset does one come to the conclusion that language cannot possibly refer to God (ibid).

Sociology, psychology, and ordinary life receive similar treatments. The point which continues to be pressed is that ideologies which reject God at the outset will, of course, reject God in the conclusions.

Analysis

Inerrancy and Worldview was a mixed read for me. Poythress at times does an excellent job explaining points of presuppositional apologetics, but at others he seems to be floundering in the vastness of the topics he has chosen to discuss.

There are many good points Poythress makes. Most importantly is his focus on the concept of one’s worldview as the primary challenge to Biblical authority. It seems to me that this is the most important thing to consider in any discussion of inerrancy. If theism is true, inerrancy is at least broadly possible. If theism is false, then inerrancy seems to be prima facie impossible.

The continued focus upon the fact that worldview largely determines what one thinks about various challenges to the Bible is notable and important. In particular, Poythress’ conclusion about challenges from religious language is poignant. The notion that we can’t speak meaningfully about God is ludicrous if the God of Christianity exists.

While there are numerous good points found in the book, but they all seem to be buried in a series of seemingly random examples, objections, and response to those objections. For example, an inordinate amount of space is dedicated to the OT discussing “gods” (including sections on p. 63-65; 66-70; 71-78; 79-81; 111-112; 116-117). His discussion of the Genesis creation account also left much to be desired. The “appearance of age” argument is, I believe, the weakest way to defend a Biblical view of creation.

Poythress’ discussion of feminism is also problematic. The reason is not so much because his critique of feminist theology is off-base, but rather because his definition is far too broad for the view he is critiquing. He writes, “feminism may be used quite broadly as a label for any kind of thinking that is sympathetic with gender equality. For simplicity we concentrate on the more popular, militant, secular forms” (121). But from the text it seems clear that Poythress is focused upon feminist theology more broadly speaking then secular feminism specifically. Where he does seem to express secular feminism, he still mentions the Bible in context (124). Not only that, but his definition of feminism seems to express a view which should be entirely unproblematic (“sympathy with gender equality”) yet he then spends the rest of the section as though there is some huge negative connotation with gender equality. One must wonder: is Poythress suggesting we should advocate for “gender inequality”? And what does he mean by “equality” to begin with? Sure, this section is a minor part of the book, but there are major problems here.

Furthermore, one is almost forced to wonder how this work is a defense of inerrancy. For example, the lengthy discussion of gods referenced above has little if anything to do with inerrancy. Instead, Poythress spends the bulk of this space attempting to show how the gods referenced are really idols which people worship instead of God. Well, of course! But what relevance does this have for inerrancy specifically? Perhaps it helps solve some issues of alleged errors, but solving individual errors does little to defend the specific doctrine of inerrancy.

And that, I think, is one of the major issues with the book. Poythress seems to equate rebutting specific errors with a defense of inerrancy. While this obviously has relevance for inerrancy–if there were errors, the Bible is not inerrant–it does little to provide a positive case for inerrancy.

Perhaps more frustratingly, Poythress never spends the time to develop or explain a robust doctrine of inerrancy. It seems to me that this is part of the reason the defense seems so imbalanced. Rather than clearly defining the doctrine and then defending it, he spends all his time defending the Bible against numerous and varied errors. This is important; but it does not establish inerrancy specifically. There are plenty of Christians who are not inerrantists who would nevertheless defend against particular alleged errors in the Bible.

Conclusion

Inerrancy and Worldview was largely disappointing for me. That isn’t because it is poorly written, but because I think Poythress could have done so much more. He never makes the connection between the actual doctrine of inerrancy and worldview. Instead, the connection is between specific errors and worldview. It seems to me presuppositional apologetics has perhaps the most resources available to defend the doctrine of inerrancy. Unfortunately, Poythress did not seem to utilize all of these resources to their fullest in the book. Interested readers: keep an eye out for my own post on a presuppositional defense of inerrancy.

Addendum

I must make it clear that I am an inerrantist. The reason I do this is because I have seen other critical reviews of this work where comments are left that the author of the review must not believe inerrancy. Such an accusation is disingenuous. It is perfectly acceptable to say that a specific defense of inerrancy is insufficient while still believing the doctrine itself.

Links

Like this page on Facebook: J.W. Wartick – “Always Have a Reason”.

Inerrancy, Scripture, and the “Easy Way Out”– I analyze inerrancy and why so many Christians reject it. I believe this is largely due to a misunderstanding of the doctrine.

The Presuppositional Apologetic of Cornelius Van Til– I analyze the apologetic approach of Cornelius Van Til, largely recognized as the founder of the presuppositional school of apologetics.

The Unbeliever Knows God: Presuppositional Apologetics and Atheism– I discuss how presuppositional apologetics has explained and interacted with atheism.

Source

Vern Sheridan Poythress, Inerrancy and Worldview (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

The Unbeliever Knows God: Presuppositional Apologetics and Atheism

[A]ll men already know God–long before the apologist engages them in conversation–and cannot avoid having such knowledge… People lack neither information nor evidence… [A]ll men know that God exists… In a crucial sense, all men already are “believers”–even “unbelievers” who will not respond properly by openly professing and living obediently in accordance with the knowledge they have of God. (Greg Bahnsen, Van Til’s Apologetic

, 179-180, emphasis his, cited below).

One crucial point of presuppositional apologetics is that even the unbelieving atheist really does know God. All people have knowledge of God. None can turn from it, none can escape it: everyone knows God. This knowledge is not saving knowledge. Instead, it is knowledge which is suppressed. The knowledge is ignored or even reviled. The quote above from the famed presuppositionalist Greg Bahnsen is just one example. C.L. Bolt, a popularizer of presuppositional apologetics, says similarly:

It is in the things that have been created that God is clearly perceived. This perception is, again, so clear, that people have no excuse. Not only do all of us believe in God, but we know God. (C.L. Bolt, cited below)

What are we to make of this claim? What is the point from the presuppositionalist perspective? The claim is firmly rooted in Paul’s discussion of God’s wrath against evil in Romans 1-2 (see the text at the end of this post). Therefore, it behooves all Christians to reflect upon the notion that God is known to all people. Presuppositional Apologists have done much reflecting on these subjects, and here we shall reflect upon their insights.

What is meant by ‘knowledge of God’?

What is meant by ‘knowledge of God’?

It is important to outline what exactly it is that this knowledge is supposed to be. Greg Bahnsen notes in Van Til’s Apologetic that the claim is, in part, that “[all people/unbelievers] ‘have evidence’ that justifies the belief that [God] exists” (182).

Note that there is an important distinction within presuppositional thought about what this knowledge of God means. John Frame makes it clear that there is a sense in which the unbeliever knows God and yet another sense in which the unbeliever does not know God (Frame, The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God 49, cited below). According to Frame, the unbeliever knows “enough truths about God to be without excuse and may know many more…”; but “unbelievers lack the obedience and friendship with God that is essential to ‘knowledge’ in the fullest biblical sense–the knowledge of the believer” (ibid, 58). Furthermore, the unbeliever, according to Frame, is in a state wherein he fights the truth: the unbeliever denies, ignores, or psychologically represses the truth, among other ways of acknowledging God as the truth (ibid).

Frame also makes clear the reasons why all people know God in at least the limited sense: “God’s covenental presence is with all His works, and therefore it is inescapable… all things are under God’s control, and all knowledge… is a recognition of divine norms for truth. Therefore, in knowing anything, we know God” (18). Frame elaborates: “[B]ecause God is the supremely present one, He is inescapable. God is not shut out by the world… all reality reveals God” (20).

Therefore, this knowledge should be understood as the blatant, obvious awareness of God found in the created order. It is not saving faith or saving knowledge; instead, it is knowledge which holds people culpable for its rejection. All are accountable before God.

The Implications of the Knowledge of God

The Implications of the Knowledge of God

The Practical Implications of the Knowledge of God

Of primary importance is the notion that there is no true atheism. Instead, atheism can only be a kind of pragmatic or living atheism: a life lived as though there were no God. All people know that God exists. The eminent Calvinist theologian, William Greenough Thayer Shedd writes, “The only form of atheism in the Bible is practical atheism” (Shedd, Dogmatic Theology Kindle location 5766). This means that people can live as though there were no God, but none can genuinely lack knowledge of God. Atheism is a practical reality, but not a genuine reality. The very basis for a denial of God is grounded on truths which can only be true if God exists. Here is where the distinctiveness of the presuppositional approach to apologetics

Van Til notes, “It is… imperative that the Christian apologist be alert to the fact that the average person to whom he must present the Christian religion for acceptance is a quite different sort of being than he himself thinks he is” (The Defense of the Faith, 92). His meaning is directly applicable to the discussion above. Christian apologists must take into account the fact that the Bible clearly states that those who do not believe in God themselves know God already.

Furthermore, this knowledge of God is of utmost importance. Bahnsen writes, “Our knowledge of God is not just like the rest of our knowledge… The knowledge that all men have of God… provides the framework or foundation for any other knowledge they are able to attain. The knowledge of God is the necessary context for learning anything else” (181). As was hinted at above, without God, there is no knowledge. Even the unbeliever relies upon God for any true beliefs he has. Van Til notes, “our meaning… depends upon God” (63).

Apologetics in Practice

For presuppositionalists, this means that apologetics is reasoning with people who already know and use their knowledge of God to ground whatever knowledge they do have and bringing them to an awareness of their double-standards. They reject God in practice, but accept God in their epistemology. Thus, presuppositional apologists use the transcendental argument: an argument which seeks to show that without God, the things which we take for granted (knowledge, logic, creation, etc.) would not exist.

Can evidentialists use the insights of presuppositionalists here as well? It seems they must; for the Bible does clearly state that everyone knows God. However, the way evidentialists may incorporate this insight is by using an evidential approach to bring the unbeliever into an awareness of the knowledge they are rejecting in practice. Thus, a cosmological argument might be offered in order to bring the unbeliever into an awareness that their assumptions about the universe can only be grounded in a creator.

Conclusion

We have seen that presuppositional apologetists makes use of the knowledge of God attested in all people by Romans 1 in order to draw out a broadly presuppositional approach to apologetics. I have also given some insight into how evidentialists might use this approach in their own apologetic. We have seen that the core of this argument is that all people know God. Therefore, there are no true atheists; only practical atheists. All true knowledge must be grounded on the fact of God. There are none with an excuse to offer before God at judgment. God’s existence is clear. The unebeliever knows God.

I end with the Biblical statement on the state of the knowledge of the unbeliever, as written by Paul in Romans 1:

The wrath of God is being revealed from heaven against all the godlessness and wickedness of people, who suppress the truth by their wickedness, since what may be known about God is plain to them, because God has made it plain to them. For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.

For although they knew God, they neither glorified him as God nor gave thanks to him, but their thinking became futile and their foolish hearts were darkened. Although they claimed to be wise, they became fools…

Links

Like this page on Facebook: J.W. Wartick – “Always Have a Reason”

Unbeliever’s suppression of the truth-A brief overview of the notion that unbelievers are suppressing the truth from a presuppositional perspective.

The Presuppositional Apologetic of Cornelius Van Til– I analyze the apologetic approach of Cornelius Van Til, largely recognized as the founder of the presuppositional school of apologetics.

Choosing Hats– A fantastic resource for learning about presuppostional apologetics.

Sources

C.L. Bolt, “An Informal Introduction to Covenant Apologetics: Part 10 – Unbeliever’s knowledge of God.”

Greg Bahnsen, Van Til’s Apologetic (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1998).

John Frame, The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1987).

Cornelius Van Til, The Defense of the Faith (4th edition, Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2008).

Shedd Dogmatic Theology (3rd edition, Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2003).

SDG.

——

The preceding post is the property of J.W. Wartick (apart from citations, which are the property of their respective owners, and works of art as credited) and should not be reproduced in part or in whole without the expressed consent of the author. All content on this site is the property of J.W. Wartick and is made available for individual and personal usage. If you cite from these documents, whether for personal or professional purposes, please give appropriate citation with both the name of the author (J.W. Wartick) and a link to the original URL. If you’d like to repost a post, you may do so, provided you show less than half of the original post on your own site and link to the original post for the rest. You must also appropriately cite the post as noted above. This blog is protected by Creative Commons licensing. By viewing any part of this site, you are agreeing to this usage policy.

The Crusades: Wanton Religious Violence?

The Crusades are often cited as the prime example of the evils of religion and of Christianity specifically. The picture is often painted of an innocent world on which Christians came in violent fervor, raping and pillaging as they went. But this picture of the Crusades is inaccurate on a number of levels. Here, I’ll explore the historical context of the Crusades with an eye towards seeing why they occurred. I’ll wrap it up with a discussion on violence and religion.

The Crusades are often cited as the prime example of the evils of religion and of Christianity specifically. The picture is often painted of an innocent world on which Christians came in violent fervor, raping and pillaging as they went. But this picture of the Crusades is inaccurate on a number of levels. Here, I’ll explore the historical context of the Crusades with an eye towards seeing why they occurred. I’ll wrap it up with a discussion on violence and religion.

The Historical Context of the Crusades

The Crusades were not just some bubbling up of violence latent within all religions. Instead, they were part of a history of conquest across the Asian and European continents. Prior to the Crusades, there was a sweeping conquest by the Muslims of territory formerly possessed by various Christian nations.

Muslim invasions had pressed in on all sides. Rodney Stark, in his extremely important work on the Crusades, God’s Battalions, notes the conquests which had pressed in on Europe from all sides. After surveying a number of Muslim conquests, he notes:

Many critics of the Crusades would seem to suppose that after the Muslims had overrun a major portion of Christendom, they should have been ignored or forgiven… This outlook is certainly unrealistic and probably insincere. Not only had the Byzantines lost most of their empire, the enemy was at their gates… (32-33)

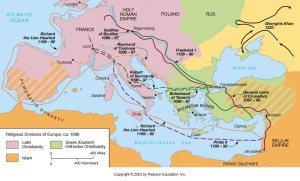

Prior to the Crusades, it is absolutely essential to note that the invaders were, quite literally, at the gates. Constantinople was threatened in the East, and Spain was overthrown in the West. Europe was under assault. The map below illustrates the situation in the time during and before the Crusades well.

The question of the Crusades must be understood within this historical setting: much of the land which European countries had controlled had been taken, by force. Furthermore, those who had taken these lands were knocking on the very gates of Europe, having already crossed into Europe in many places. Stark’s words, therefore, seem to ring true: is it really genuine to assume that these invaders should have been ignored or forgiven? Is that the reality of “secular” nations? It seems to me the very fact that so much land had been lost, as well as so much wealth, would lead many to war for “secular” reasons rather than religious reasons.

Regarding the beginning of the Crusades, Stark writes:

[T]hat’s when it all [The Crusades] started–in the seventh century, when Islamic armies swept over the larger portion of what was then Christian territory: the Middle East, Egypt, and all of North Africa, and then Spain and southern Italy, as well as many major Mediterranean islands including Sicily, Corsica, Cyprus, Rhodes, Crete, Malta, and Sardinia. (9)

So the Crusades were not unprovoked mass murders of innocents. But they were indeed quite brutal, and involved no small amount of very un-Christian activities. Raping and pillaging has no part in the Christian worldview. But Stark once again has a sobering point: war was hell. “[I]t was a brutal and intolerant age” (29). The criticism of brutality equally applies to both sides, but it is also equally anachronistic about the realities of that time. This is not to say that the horrors which occurred were not awful; it is to say that to criticize the Crusaders or Muslims as though they were doing something extraordinarily brutal for their time period is extremely short-sighted.

The Crusades as a Polemic Device

The Crusades were not all-good or all-evil affairs. Like virtually any part of human history, both good and evil intentions and outcomes were involved. To view the Crusades as either an entirely evil affair showing how religion is ultimately prone to violence or as a benevolent attempt by loving people to liberate lands that were rightfully theirs is to grossly oversimplify the historical reality. Unfortunately, modern looks at the Crusades have largely leaned towards the former of these positions, without any acknowledgement of the historical context as noted above.

Instead, the Crusades were a complex of historical events which were often brutal, often provoked, and never motivated for just one reason. To say that the Crusades are a typical example of the violence of religion is, frankly, ahistorical. Was religion involved? Yes. Were there even “religious reasons” involved in the motivations for the Crusades? Clearly. But the general movement with recent attacks on Christianity has been to argue that the Crusades were purely religious instances of religious brutality. The historical perspective provided above provides evidence against that limited perspective.

The Crusades have been used as a kind of polemic device against Christianity. Whenever it is argued that Christianity is reasonable, someone inevitably brings up this historical period. Readers will note that this historical perspective has not attempted to explain away the Crusades. Instead, I have argued for the notion that these events were historically complex, involving a number of factors beyond purely war for the sake of a faith.

As Keith Ward has noted:

It is… beyond dispute that the Crusades were a major disaster… The Crusades can be seen as justified defense… but their conduct and continuance rapidly became unjustifiable on any Christian principles. (68-69, Is Religion Dangerous?

cited below)

The point is simple: there were many motivations behind the Crusades, some of them justified. Yet in carrying out the Crusades, many horrible actions were taken which were unjustifiable. Does this somehow disprove Christianity? Not on Christianity’s own principles, on which we expect to see people acting as sinner-saints in the process of sanctification.

Religious and Secular Violence

Religious and Secular Violence

Apart from the historical outline given here, there is another, equally important point: the dichotomy between religious violence and secular violence is simply a myth. The reason for this is because human actions are far more complex in their motivations than a simple dichotomy of one or the other reason. In our everyday experience, we know that the decisions we make are very rarely made for only one reason.

Oddly, Stark is able to note that “many historians have urged entirely material, secular explanations for the early Muslim conquests…” (13). This, in contrast to the many historians and new atheists who continue to press that the Crusades were entirely religious in their provocations. The unfortunate truth this reveals is the very human tendency to simplify history beyond the point of breaking. Human actions, particularly corporate human actions, have extremely complex motivations behind them. They are not all-or-nothing affairs which happen due to one reason or another. Very often we make decisions for a combination of reasons of differing strengths, weighing options against each other whether we realize it or not.

By utilizing the Crusades as a rhetorical device–a polemic weapon–many have done damage to the historical events themselves. Worse, they have engaged in faulty reasoning and attacked the religious other due to their own emotional hatred. The Crusades were not all-good or all-evil affairs. They were affairs of human history. To forget that is to drown them in a sea of obfuscation. Let us get beyond simple polemical attacks on the “other.” Let us instead engage in honest history and dialogue with our neighbors.

Links